Random Stuff

Trying out still more page formatsJust A Standard Page

Nunc et vestibulum velit. Suspendisse euismod eros vel urna bibendum gravida. Phasellus et metus nec dui ornare molestie. In consequat urna sed tincidunt euismod. Praesent non pharetra arcu, at tincidunt sapien. Nullam lobortis ultricies bibendum. Duis elit leo, porta vel nisl in, ullamcorper scelerisque velit. Fusce volutpat purus dolor, vel pulvinar dui porttitor sed. Phasellus ac odio eu quam varius elementum sit amet euismod justo. Sed sit amet blandit ipsum, et consectetur libero. Integer convallis at metus quis molestie. Morbi vitae odio ut ante molestie scelerisque. Aliquam erat volutpat. Vivamus dignissim fringilla semper. Aliquam imperdiet dui a purus pellentesque, non ornare ipsum blandit. Sed imperdiet elit in quam egestas lacinia nec sit amet dui. Cras malesuada tincidunt ante, in luctus tellus hendrerit at. Duis massa mauris, bibendum a mollis a, laoreet quis elit. Nulla pulvinar vestibulum est, in viverra nisi malesuada vel. Nam ut ipsum quis est faucibus mattis eu ut turpis. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Maecenas nunc felis, venenatis in fringilla vel, tempus in turpis. Mauris aliquam dictum dolor at varius. Fusce sed vestibulum metus. Vestibulum dictum ultrices nulla sit amet fermentum.

Achievements of a Goal-Oriented Individual

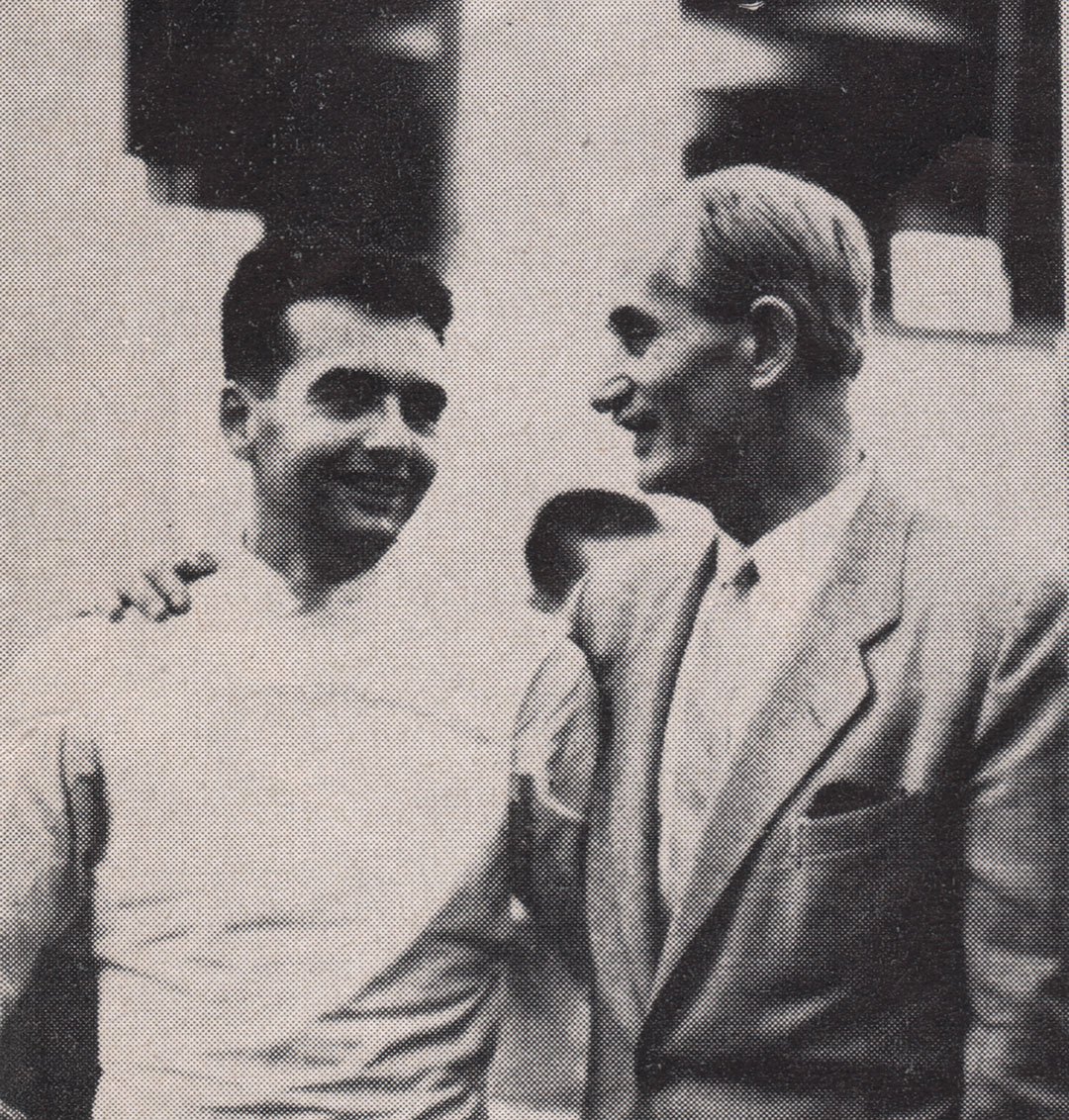

Carl Borack was something of an enigma to me when I first encountered him in 1979. By that time, he had traveled the world, won the US Nationals (foil), been on an Olympic team and produced his first feature film in Hollywood. After 2 years at Cabrillo Community College, I had transferred to San Jose State to train under Michael D’Asaro. Carl, good friends with Michael and many of the San Jose fencers, would stop into the 7th Street salle when he was in town visiting Mike & Gay. Now, I don’t know if others have felt the way I did as a young whippersnapper but when I would meet a ‘retired’ competitor, regardless of their past success, I put them in a particular corner of my mind. “You don’t have to know how to beat them. Focus on others.” Likewise, I imagine, Carl may have seen in me (and it’s unlikely I was noticed) an uninspiring college student of Michael’s with just a couple of years of fencing under his belt and a long way to go to break into the top ranks of that National fencing scene. (I never did.) Since I wasn’t in Michael’s social circle, I didn’t have an opportunity to cross paths with Carl in a non-fencing venue.

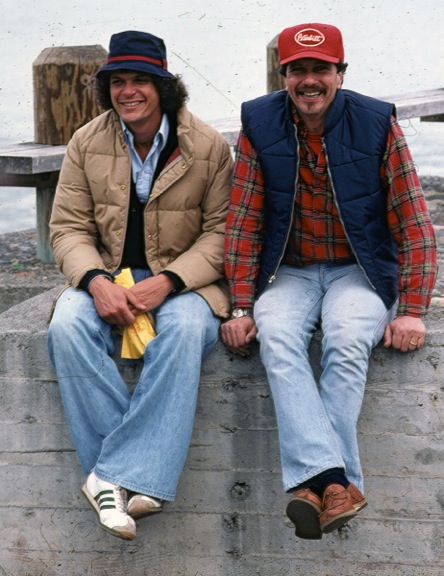

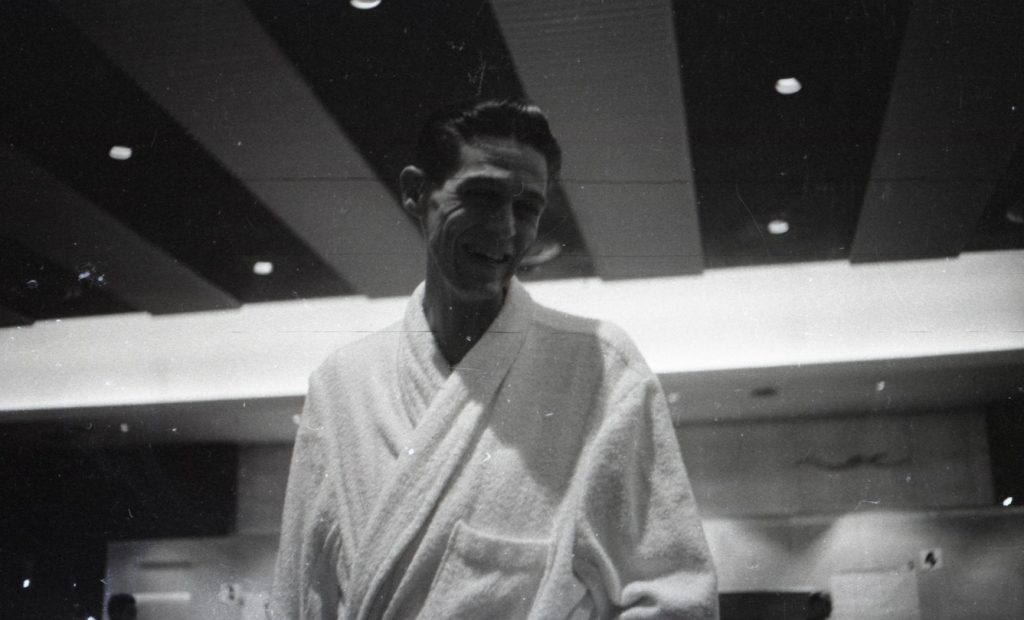

Carl and Michael D’Asaro trying to stay warm at a Nor Cal beach in 1979.

But what really caught my attention was learning that Carl worked in Hollywood. I had dreams of Hollywood work, although my primary interest was in animation rather than live action, Carl’s bailiwick. Still. Carl was one of the handful of people I ran across prior to the start of my own career who helped me realize that working in Hollywood was an achievable goal. Not because I’d do the same work as those who influenced me to pursue it, but because I recognized that there was space. People got work. What kind of work had to be figured out or fallen into, but work was there to do. Find it, make it, whatever, it was an achievable goal.

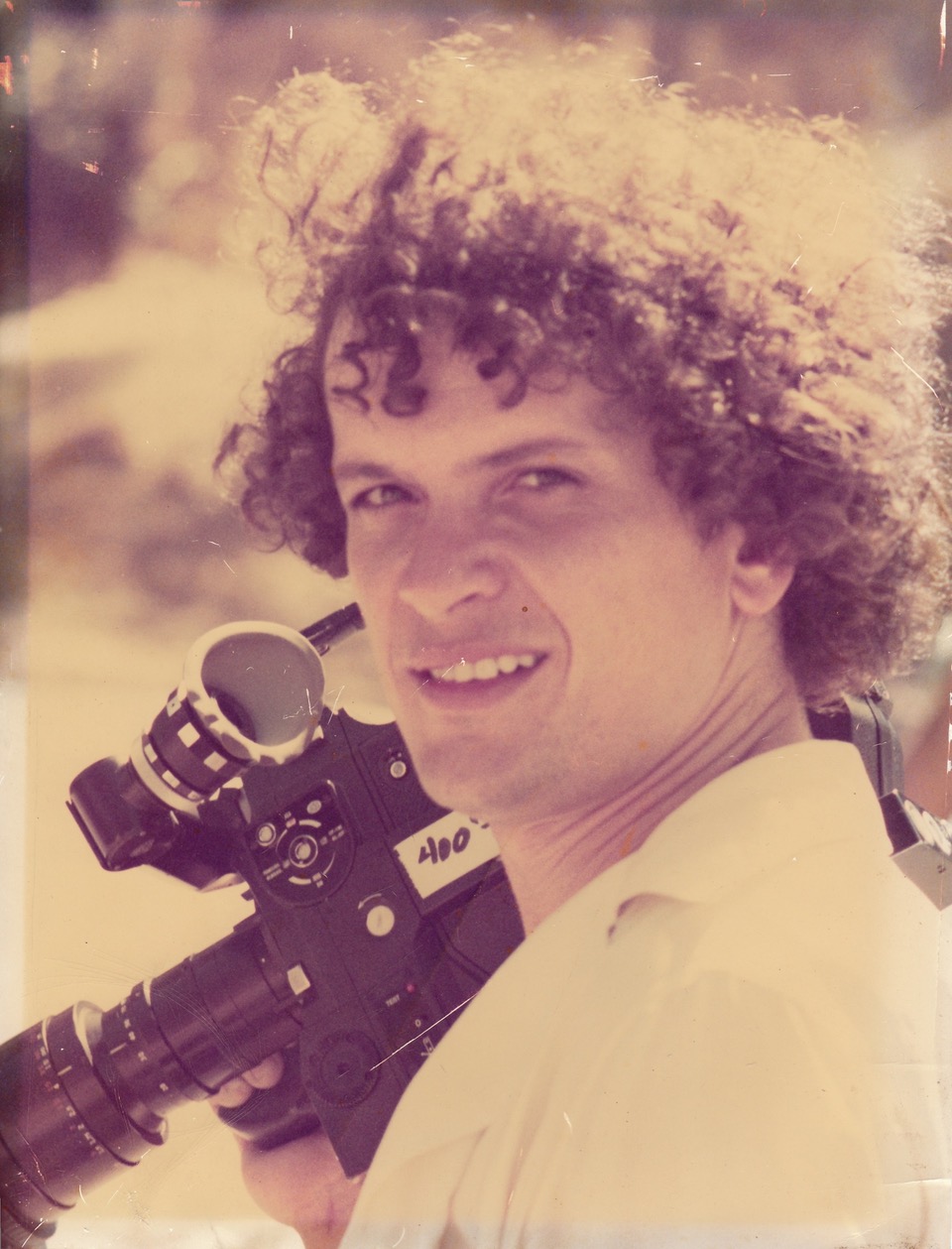

A young Hollywood entrepreneur. With camera.

When I think about the influence Carl had on me, a peripheral, unintended consequence in the best light, and then think about the impact Carl has had on the fencing community as a whole, I am taken aback, realizing that the influence he has wielded in that world has been entirely intentional on his part. His focus on the needs of our community has driven him to attain goals that have helped dozens, if not hundreds, of fencers in the past 40 years and will continue to influence the success of US fencing for the foreseeable future.

The first go-round with fencing. Carl at the age of 9 with jacket, glove & swords.

Carl began fencing at the age of 9 in his home town of Los Angeles, California at an afternoon program at the Westside Jewish Community Center, a short hop from the famous Miracle Mile. His coach was Mel North. Carl enjoyed it so much he began to attend Mel’s club on Saturdays to supplement his one-day-a-week school class. After a year, Carl’s family moved and fencing stopped until his freshman year of high school. Frustrated with freshman football, a friend suggested they take up fencing and Carl agreed to try again. So at 14, Carl once again found himself in a fencing club and once again his coach was Mel North.

Mel was a fixture in LA’s fencing scene at the time and for many years to come, coaching both at his own club, Salle du Nord, and at UCLA. He gave Carl a superb grounding in the sport, teaching at once a classical style coupled with excellent tactics and strategy. Mel was a passionate coach, tough on opponents and officials, but dedicated to the success of his students.

The program cover for the 1965 Junior World Championships, Carl’s first international fencing event.

Carl had so dedicated himself to the sport that in 1965 as a high school senior, age 17, he traveled to Rotterdam, the Netherlands, to attend the Junior World Championships. The Junior World event had only been taking place since 1953, and in 1965 the United States did not field a team or send representatives, so Carl was essentially on his own. He traveled with only his own coach for support. The US didn’t begin to send fencers or cadre to the JWC’s until 1968, after Carl had single-handedly proven the benefit of the experience. The Junior Worlds were eye opening for Carl. Here was his first opportunity to witness the pinnacle of fencing, which in turn enlarged the vision for his own potential. He returned to the following year’s Junior Worlds, this time on his own, in Vienna. Also in 1966, he won the first ever US Under-19 National Championships in epee, and traveled with Salle du Nord teammate Joe Elliot to Moscow for his first Senior World Championship.

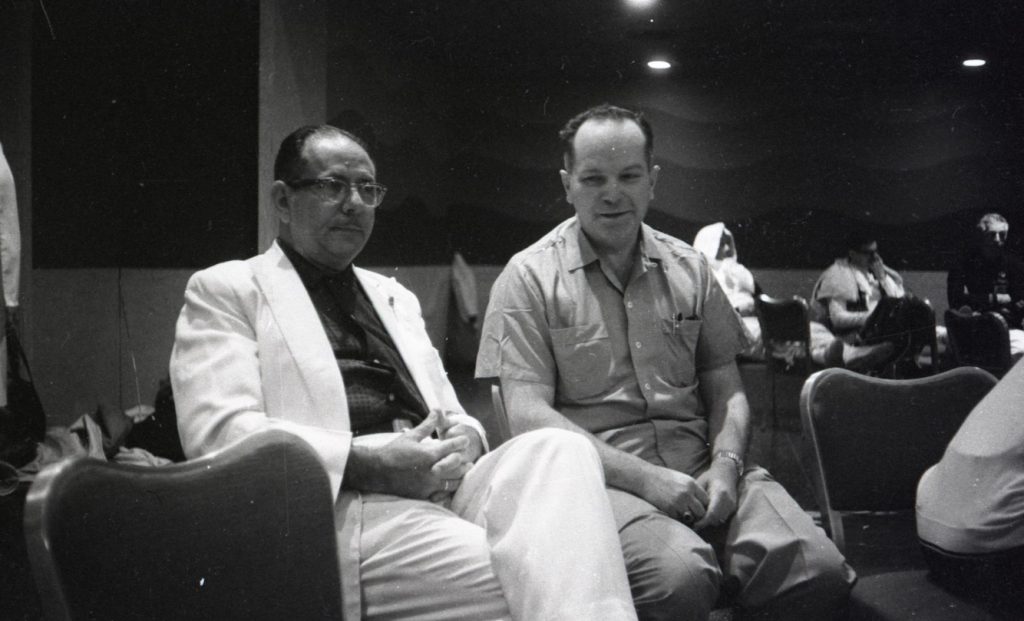

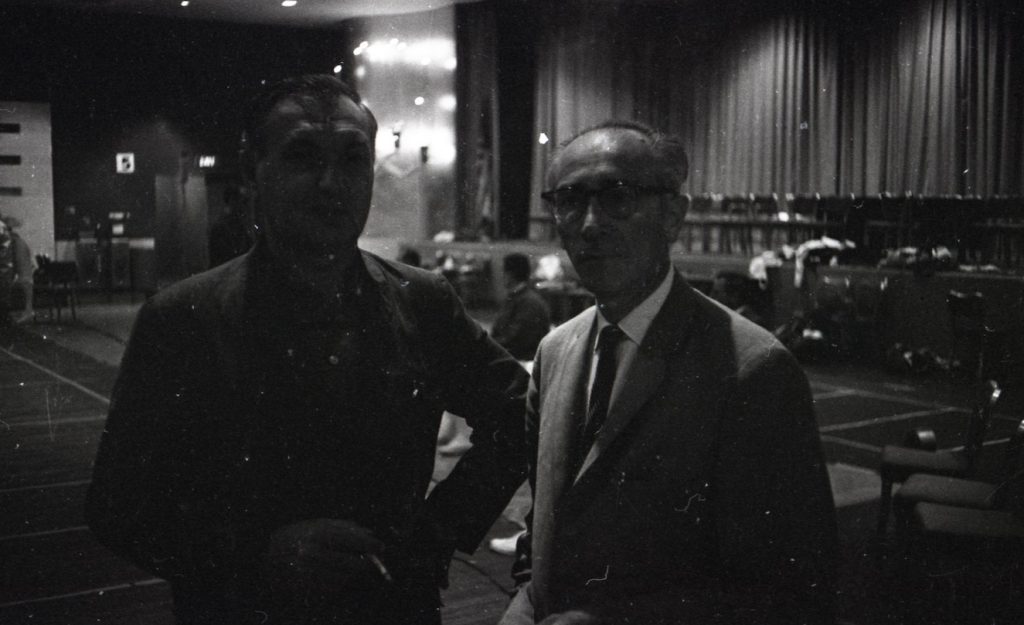

Carl Borack and Joe Elliot at the 1966 World Championships in Moscow.

These exceptional experiences were a springboard to additional success in US National events. He took 3rd in the epee Nationals in 1967, his first Senior final, which qualified him for the Pan American epee team that won Gold in Winnipeg, Canada. In 1968, Carl made the Olympic Squad in both foil and epee, ending the season as 2nd alternate to the Olympic epee team, and in 1969 won the Men’s Foil National Championship. In the years between team selections, Carl had excellent results at many major competitions including the Maccabiah Games and the Pan American Games but honestly, his performance at the 1971 Nationals where he made the finals – in all three weapons – has to be the most astonishing feat of all. From there, he was selected to be on the foil team for the 1972 Munich Olympics.

In 1969, 21 years of age. At that time, he was the youngest fencer ever to win the US foil title.

Post-Olympics, with a few forays back into the mix, Carl retired from competition to focus on his professional career as a producer in Hollywood, where he has been very successful and covered a lot of different ground. Movies, commercials, plays, documentaries. He’s been in it and around it, fighting and winning those battles over the years, and probably losing a few bouts along the way as well. It’s Hollywood after all. As a metaphor for fencing, it seems apt.

However it’s the choice Carl made to support fencing in his own particular way that makes his contribution to the sport so unique. What he recognized after completion of his competitive career was that support for athletes trying to make their way at international competitions had barely progressed from how things had been in his own experience. That is to say, slightly better than non-existent. With purpose and intent, he set out to make a difference in that arena. In 1977, he met up with the US Junior World team in Vienna, Austria to, in his words, “take care of them”. He did this on his own time and his own nickel. Barely 10 years removed from his personal experiences of traveling to international competitions without cadre or support of any kind, he had a very clear notion of the type of issues facing the individual athletes and stepped forward to make a positive difference for this next generation of fencers.

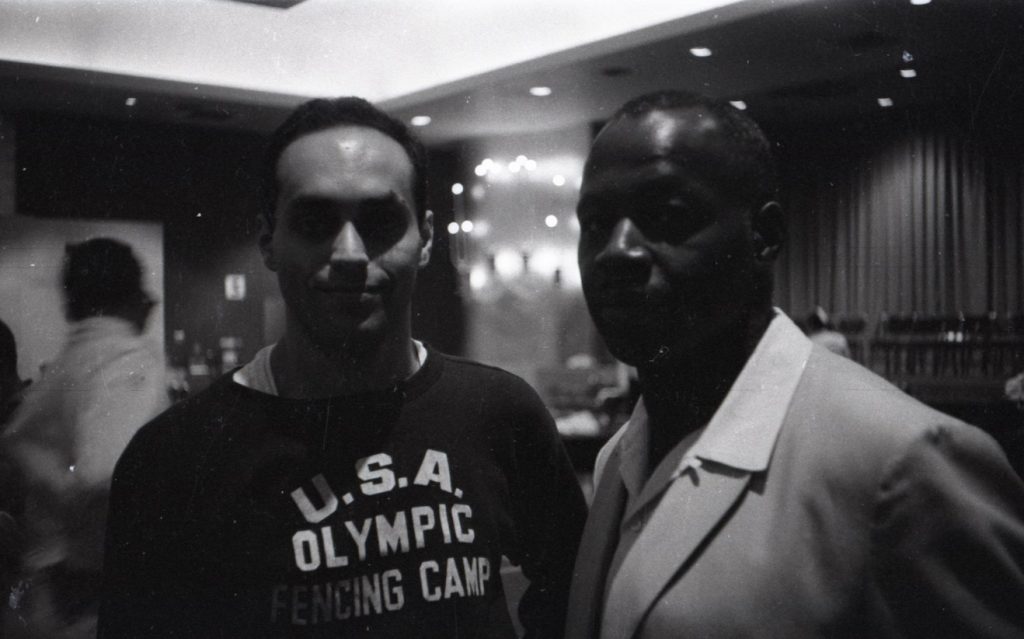

In Vienna, 1977, Carl stands, left, with Jean-Jacques Gillet, Yves Auriol and Michael Marx. Since he was at the event in an unofficial role, Carl didn’t get the same vintage sweats the others had. You can see that Yves and Michael’s suits have a USA Fencing patch on the left side, while Carl’s shows the USA letters.

I heard an athlete’s perspective about this by talking with Michael Marx, eight time US National Individual Foil champion, Silver medalist at the World University Games and five-time Olympic team member – four in foil, one in epee. Now, there is a great back-story to tell about Michael’s meeting up with Carl in Vienna for the 1977 Junior World Championships and what it meant to him personally to have Carl’s help and support but that’s going to require its own telling on another day. For now, let’s say that Michael had known and respected Carl for several years. Indeed, Carl had provided effective advice at a critical moment to help propel Michael as a then-17 year old to his first National title. Vienna was different. Carl had taken on a semi-formal role with the team and made his presence felt by providing kindness, timely advice and inspirational leadership. He stood up fearlessly to authority when needed, providing a backup for the athletes that, on his own at international competition, he’d never himself had. It would be a few years before Carl was recognized by fencing’s governing body for his contributions and given formal roles with teams but Vienna set the stage for engagement in this new role.

Carl in front of the team at the 1985 World University Games in Kobe, Japan.

That innate quality, to support and defend, is something that can be all too rare. And its interesting to me that it comes out in Carl so clearly in his work with fencers. That other world he roams where he’s made his career, the Hollywood Producer world, has many fewer examples than the national average of the kind of quality that Carl has revealed of his true nature. Does he only expose this side of himself with fencers? I’m sure Hollywood reveals a side of him as tough negotiator and hard nose player when needed. But then, he was, at his time, the youngest National Foil champion ever. So he was already tough. “Hollywood”, in the broadest sense, can be rife with deceit and treacherous paths. Not all aspects of it certainly, and there is a very wide array of niche Tinseltown realities. My career took me into the realm of visual effects and animated cartoons, and while even that world is not always happiness, glee and chocolatey snacks, its usually a step removed from the Hollywood craziness of scripts in turnaround and casting couch horrors. Looking at Carl Borack through the long lens of all he has done for the sport of fencing and how he has made it his own mission to lend support and care to the driven and passionate athletes that have made up the batting orders of our teams over the last several decades, he’s revealed a positive, motivating inner nature that shines clearly through his contributions to the sport. Where he first saw need, he stepped forward to try to fulfill that need. As time went on, he took on greater and greater roles of responsibility. But it’s hard to question that his motivation has always been to smooth the path for the fencers who came along after his own time of raising the cup on the piste. My guess about Carl running a production company in Hollywood? He’d have your back. And it doesn’t get better than that.

Carl with Nick Bravin, 1996 Atlanta Olympic team White House visit.

There’s a lot more that could be said of Carl’s achievements in his career and his passion for promoting fencing and fencers. The goals Carl set and attained in his effort to form a better support system for the athletes our coaches across the country work tirelessly to prepare have materially shaped the kinds of results we see today from the performance of our fencers. Our fencers are as good as anybody. Some have stood at the very apex of our sport, an accomplishment hardly imaginable thirty years ago. Of course, a great number of people have played a part in the rise of the American fencer. Carl’s contributions, big and small, the subtle ones and the personal ones, helped crack the frame that held us in check. Americans are up on the podium at World Cups and Grand Prix events and no one is surprised. Just remember, those podium steps didn’t make themselves. Each one was a little plan accomplished, an idea attained. Carl Borack had plans and ideas formed through his own experience and was willing to supply the vision and sweat equity to help make dreams come true for a younger generation of competitors. Dream it, achieve it. That gets it done.

Daniel Magay, Part 2

As a member of the Hall of Fame committee for USA Fencing, I get a chance to participate in an annual ritual of determining, in the fairest way possible, who is to be considered for inclusion into that prestigious body. But in the long run, just like every member of USA Fencing, I only get one vote. However, if my website is good for anything, it’s good for providing me a bully pulpit from which to tell stories to keep alive memories of fencers who deserve to be remembered.

So please. Let me talk story to you about Dan Magay. (I’ve told part of it before: Dan pt 1.)

In 1956, as the Olympics were playing out in Melbourne, Australia, a much more dramatic, world-changing event was playing out in the streets of Budapest, Hungary. The Hungarian Revolution was crushed by the Soviets and hopes that Hungary might join the world community beyond the Iron Curtain were dashed. Just as the Hungarian Olympic athletes had to individually determine their future, so, too, did the Hungarians back home. In the end, hundreds of thousands of Hungarians escaped during the time right after the Revolution ended. At the same time, a plane full of Olympic Athletes flew from Melbourne to San Francisco. With all the myriad changes made in the lives of all these refugee, as well as the changes to America and American society that resulted, the impact upon the American fencing scene can’t be overstated.

In particular, American sabre fencing was remade overnight. Coaches George Piller, Istvan Danosi and Csaba Elthes were hugely impactful. And the list of competitive fencers is like a Murderer’s Row of talent. Alex Orban, Tom Orley, Atilla Keresztes, Eugene Hamori, Csaba Pallaghy, George Domolky – all of these fencers finished up and down the list of National Sabre finalists for the next 15 years. But the best of them all was Dan Magay.

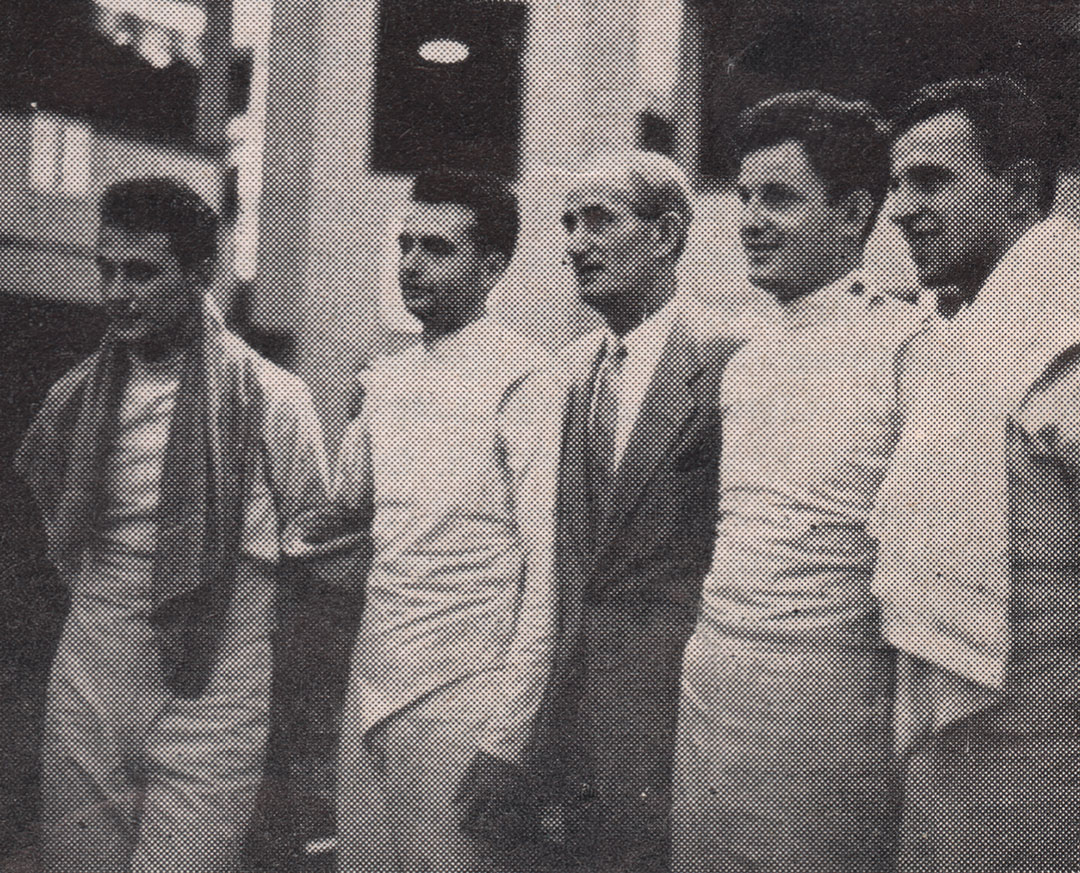

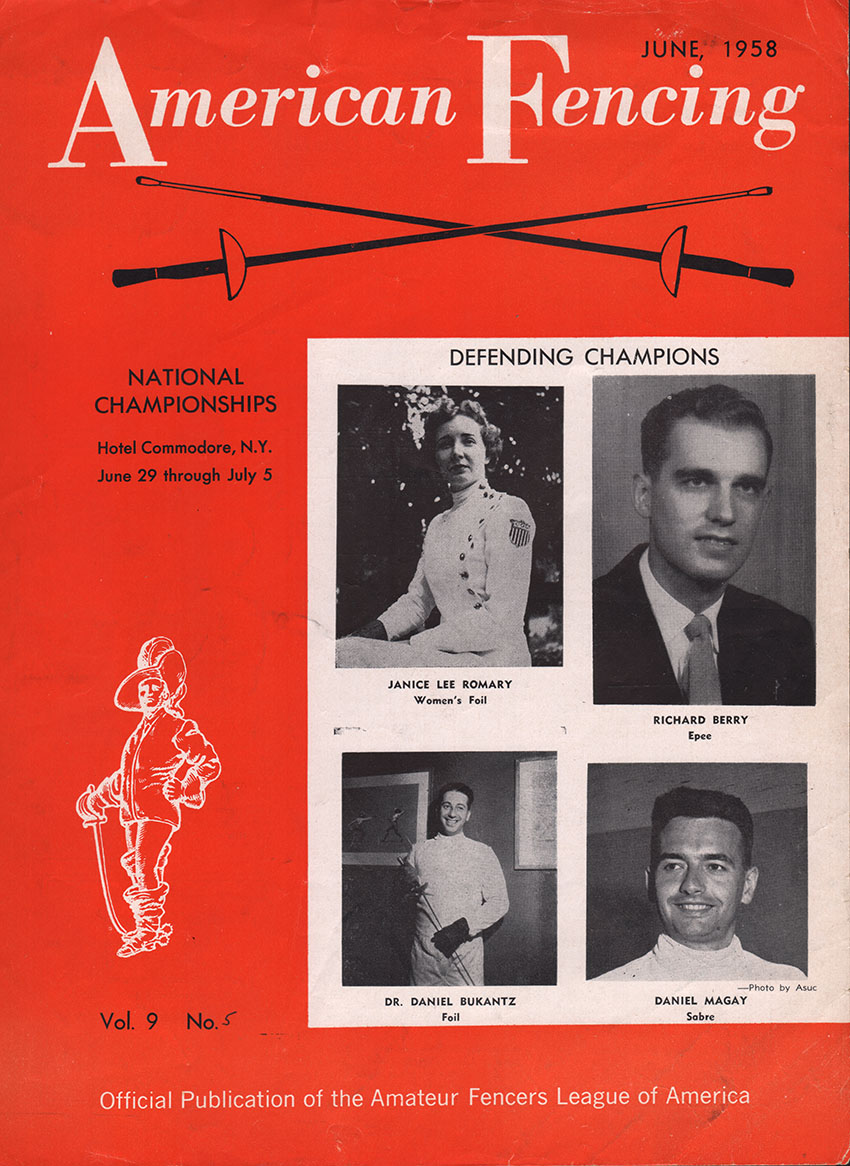

A fencing version of Murderer’s Row: Tom Orley, Dan Magay, George Piller, Eugene Hamori and Csaba Pallaghy. Taken at the 1958 Nationals.

“Dan was who I hoped to emulate.” Alex Orban said that, he of five US National titles and three Olympic team berths. Long time Magay club mate Gerard Biagini put it this way. “Dan was the epitome of what a sabre fencer wanted to be.”

Magay immediately made his presence felt at the very first post-Hungarian Revolution US Nationals in June of 1957, defeating 7-time US sabre champion and Olympic Bronze medalist (team), Dr. Tibor Nyilas and 1954 Junior World Champion Tomas Orley in a 3-way fence off. Magay dropped only one bout the whole day, to teammate and childhood friend Orley, in the final round-robin pool of twelve fencers, going 22-1 for the event. His Northern California team, consisting of himself, Orley and George Domolky – and coached by Piller – won the sabre team title as well. When deciding to travel from their new home in California to Milwaukee for Nationals (they bought a used car and drove), Domolky asked Piller if the three teammates had a chance to win. He answered simply, “Don’t worry.”

Magay with his Olympic coach, Jekelfalussy Piller György, himself a World Champion and Olympic Gold Medalist in sabre.

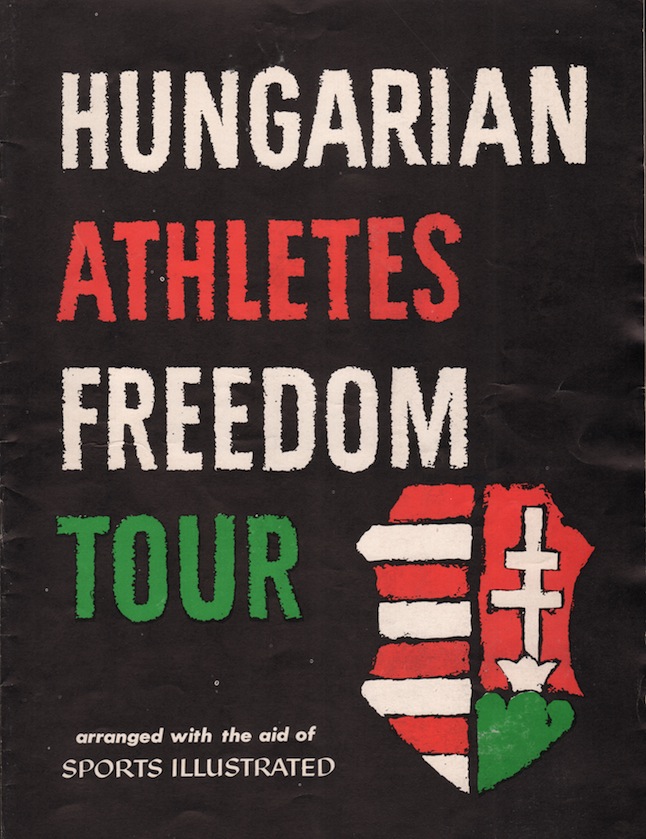

All this happened just a few months after the conclusion of the Freedom Tour, a whirlwind nationwide whistle stop that started in New York and ended in San Francisco, where Hungarian athletes put on demonstration events at 25 venues from January to March of 1957.

The Freedom Tour program cover. Sports Illustrated not only paid for the tour, they were the ones who chartered the plane that flew the Hungarian athletes and coaches from Melbourne to San Francisco.

Magay, Domolky, Hamori and others participated in this while trying to decide their future in their new country. Recruited heavily as they traveled from city to city, Hamori settled in Philadelphia. Orley and Domolky received admission to Stanford. Magay, through the assistance of an acquaintance, was accepted into UC Berkeley.

Dan as a student at UC Berkeley, where he studied Chemical Engineering.

Between school and work, training in fencing took a back seat in all of their lives. This, after living in a situation where fencing was their entire life, was the new model for survival. In Hungary, Magay, alongside Hamori, Keresztes, Orley, Pallaghy and Domolky, had been among the elite athletes, training and fencing full time in preparation to step up to replace the older generation of fencers who had dominated the world sabre scene for decades. The Big Three in Hungary, Aladar Gerevich, Pal Kovacs and Rudolf Karpati, were aging out of the sport. Indeed, Gerevich had been on the Hungarian sabre squad since 1931. Magay, Hamori and Keresztes had been the top contenders to take their spots for the 1960 Olympics. Magay was on the gold-medal winning 1954 World Championship team for Hungary and made the individual finals. Hamori and Keresztes were both on the 1955 team that, likewise, won the team gold. And while the three younger fencers had made the decision to defect from Melbourne, there was no bitterness on the part of the older fencers who remained. Indeed, in later years during an interview for a Hungarian documentary on the country’s domination of sabre fencing, Pal Kovacs stated that if Magay had chosen to return to Hungary, he would have undoubtedly soon become a World Champion. Kovacs had reason to know, as he was a mainstay on a Hungarian squad that, irrespective of what individuals were on any given team, went undefeated from 1925 through 1958 in international competition. If the Hungarian sabremen were in attendance, they won gold.

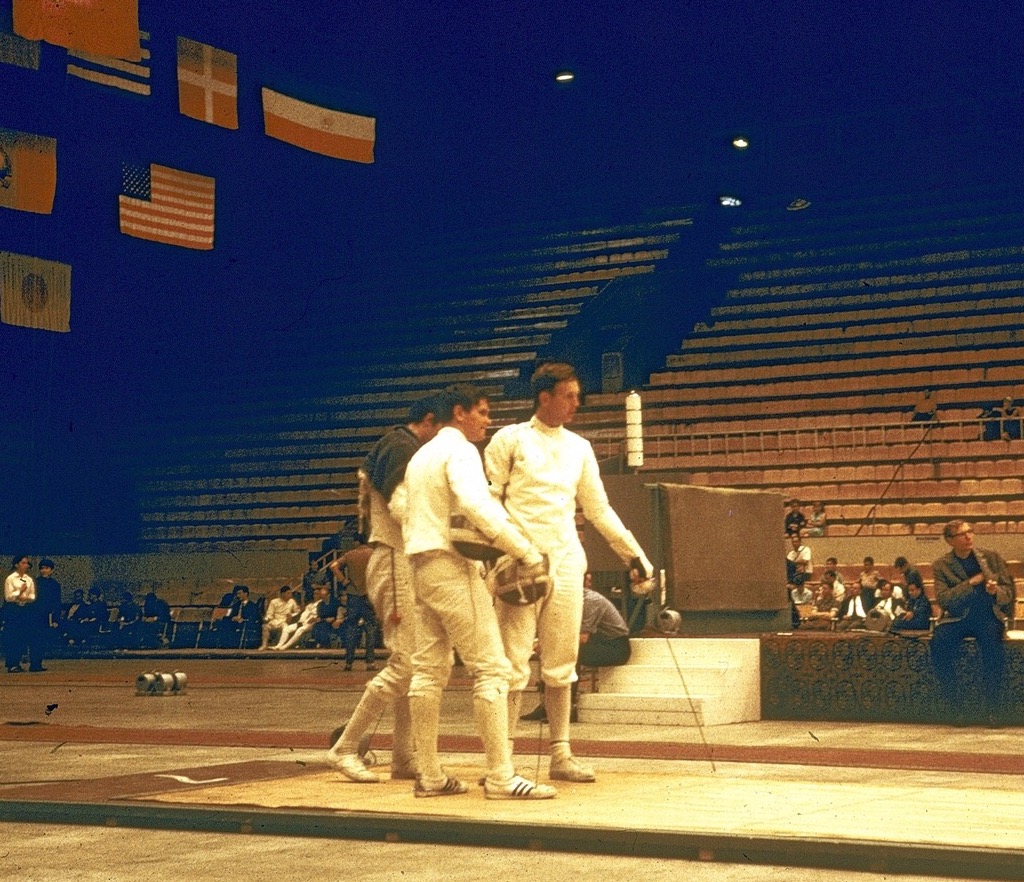

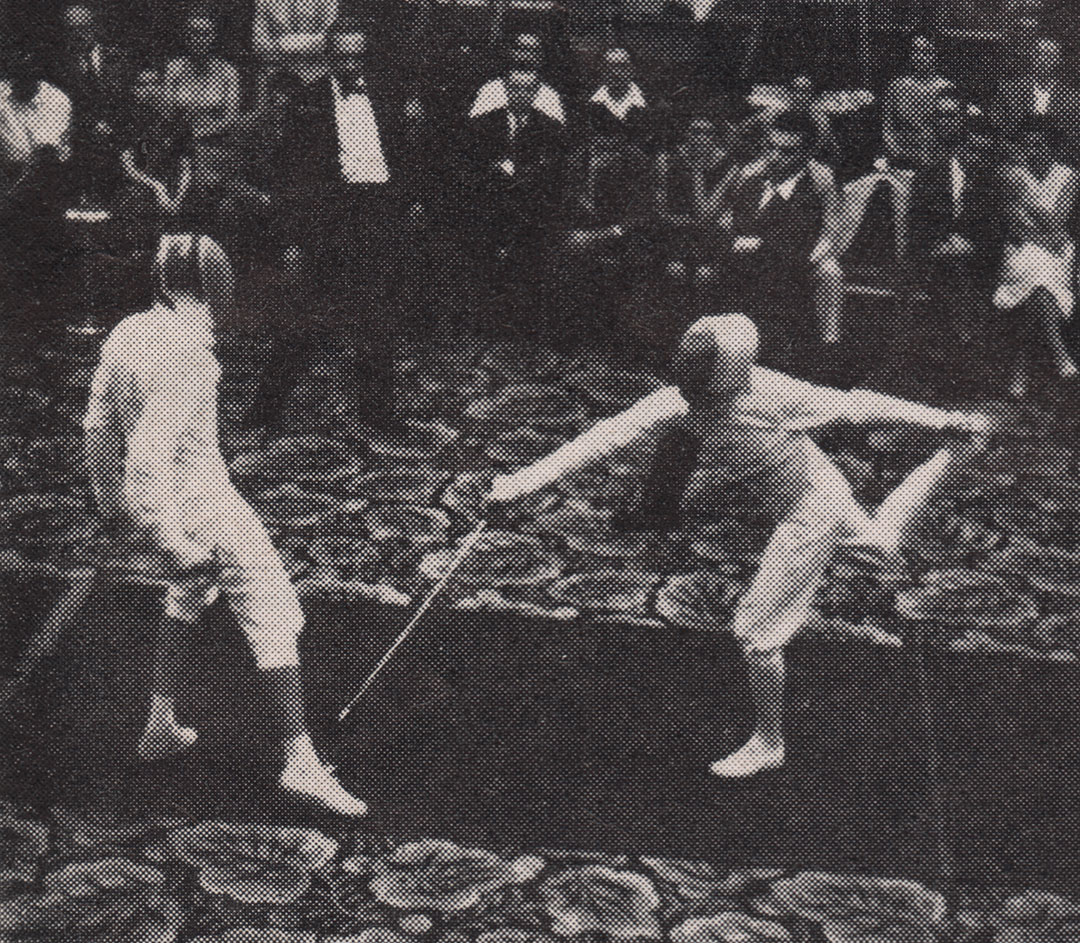

Another photo from the 1958 Nationals shows Keresztes on the left and Magay, mid-flight, on the right.

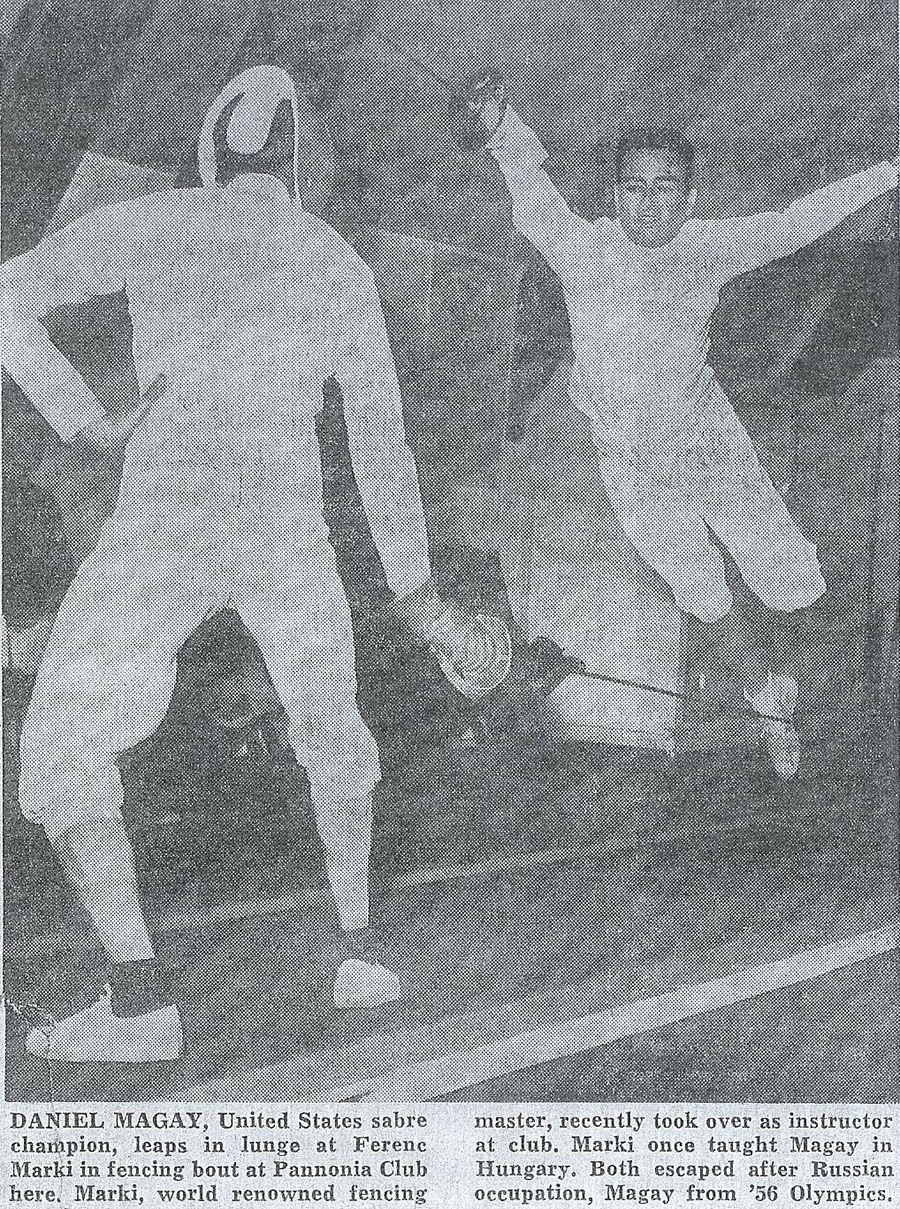

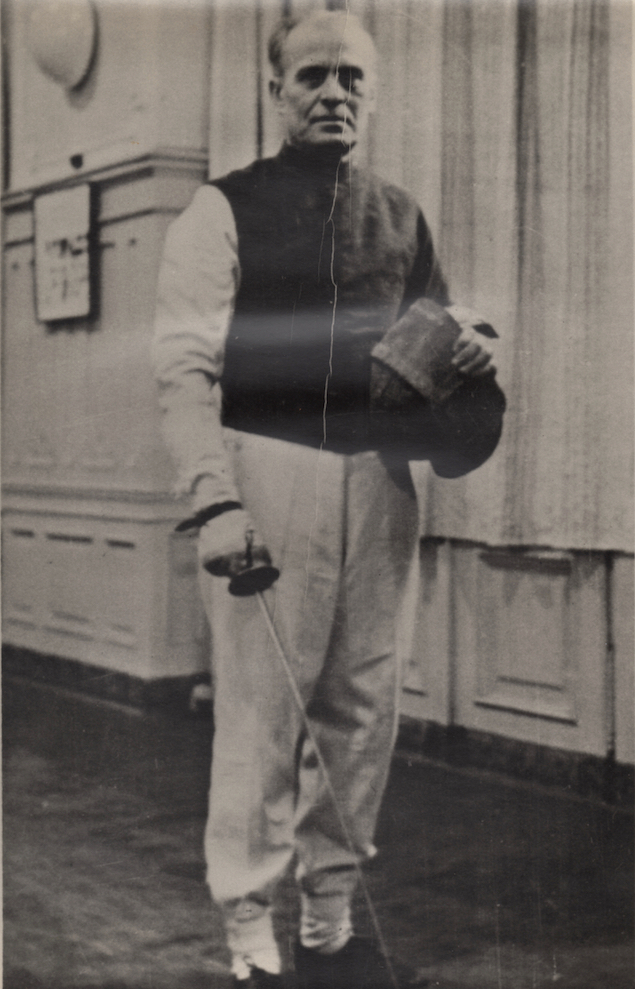

That was the tradition and expectation that Magay grew up with. In choosing the United States, he knew that the level of training and competition needed to maintain dominance would not be there. The individual coaching was still available, first with Piller and then Ferenc Marki, Magay’s main coach in Hungary, who came to the US in 1961. But the level of competition – and more, the time to focus solely on fencing – was not.

With all that, Magay still became a dominant force in the US. His individual victory in 1958 was nearly a repeat of 1957, ending with a fence-off with Nyilas. 1958 was also the year that saw Philadelphia hosting the World Championships and for the Hungarian contingent of fencers it proved to be a challenging event on many levels. At that time, the top US/Hungarian fencers, Magay, Orley, Hamori and Keresztes, were not yet US citizens. The four of them applied to participate in the World Championships as ‘stateless’ fencers. After a very intense series of meetings and votes, and over the initial objections of the Hungarian delegation, two of the four, Magay and Orley, were accepted as competitors in the individual sabre event. Three days later, after hearing no doubt an earful from Budapest, the Hungarian representatives withdrew their fencers from the individual sabre and epee events, while remaining in the team events. The stateless fencers could not field a team. (Peter Bakonyi, living in Canada, had been accepted into the epee individual event on the same basis as Magay and Orley.) To add a little additional drama, Dan Magay then had an acute attack of appendicitis and was rushed to the hospital. Hamori, the next highest ranked stateless fencer from the 1958 Nationals, was allowed to take Magay’s slot.

Hamori and Orley both proved their right to be there by making it to the semi-finals. In fact, Hamori was on fire early, finishing the first two rounds with just a single defeat. The only American entry to do as well was Robert Blum who reached the finals and finished 8th. Of course, if the Hungarians had entered Karpati, Kovacs and Gerevich, the whole outcome would have been re-written, considering that Hungarian fencers had won 16 of 21 available medals (6 gold, 6 silver, 4 bronze) in the previous 7 years of championships.

1959 was the only Nationals where Dan competed but failed to make the final, bowing in the semi’s. He did not compete at all in 1960. He came storming back in 1961, winning his third Individual title and also helping the Pannonia squad to another gold in Team. In 1962 he finished second to Michael D’Asaro after a fence-off. That was D’Asaro’s only US National individual sabre title. Interestingly, Michael was the first American-born sabre fencer to win the US title since Dick Dyer in 1955. All the rest had gone to Hungarians: Nyilas, Magay, Orley, Hamori – and they won the next three as well, with Hamori capturing a second, and Keresztes and the youngster Orban each winning one.

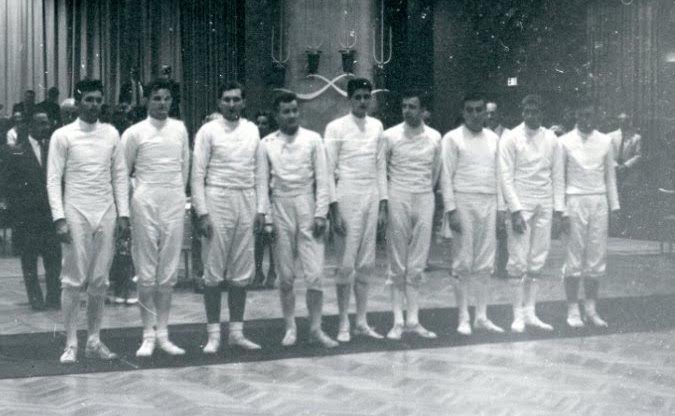

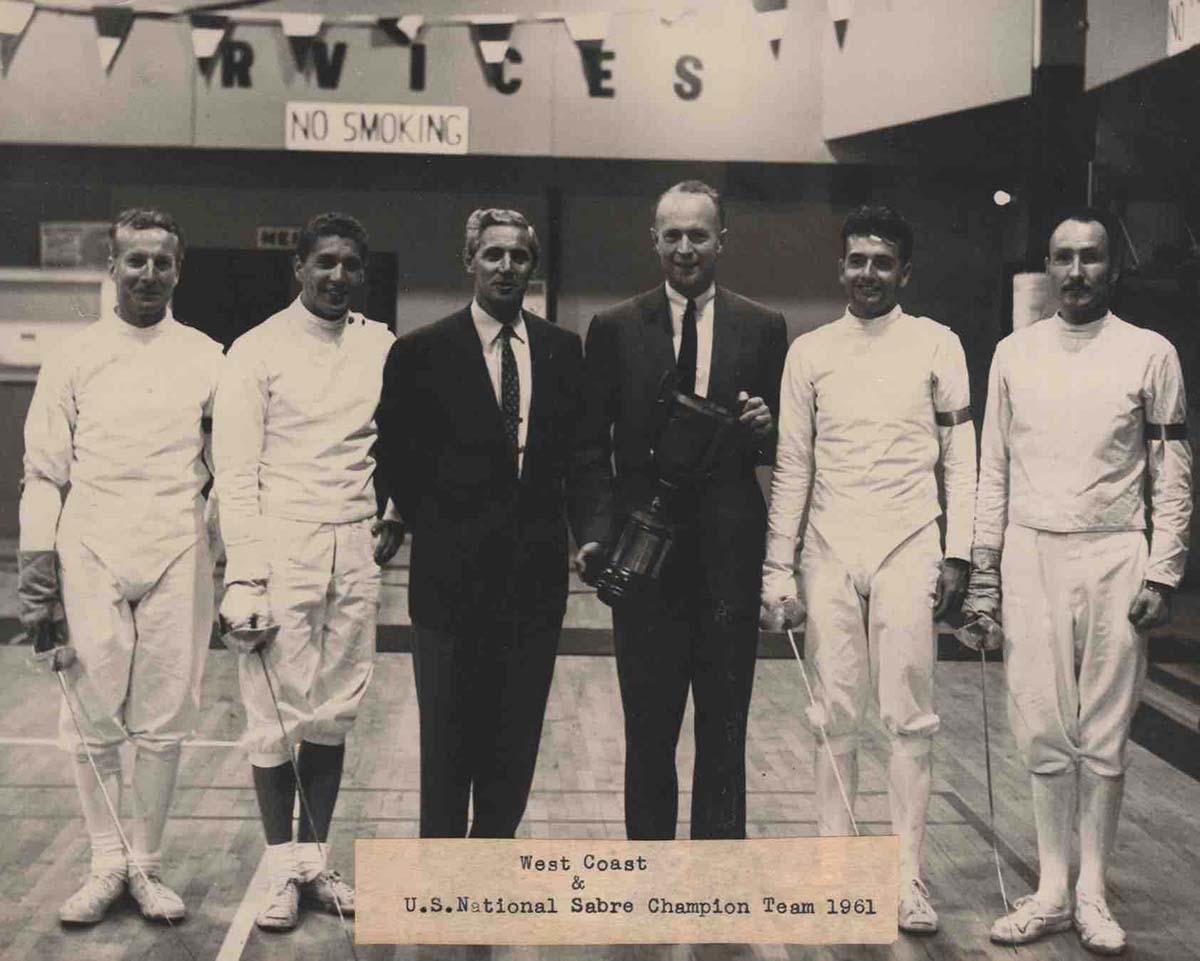

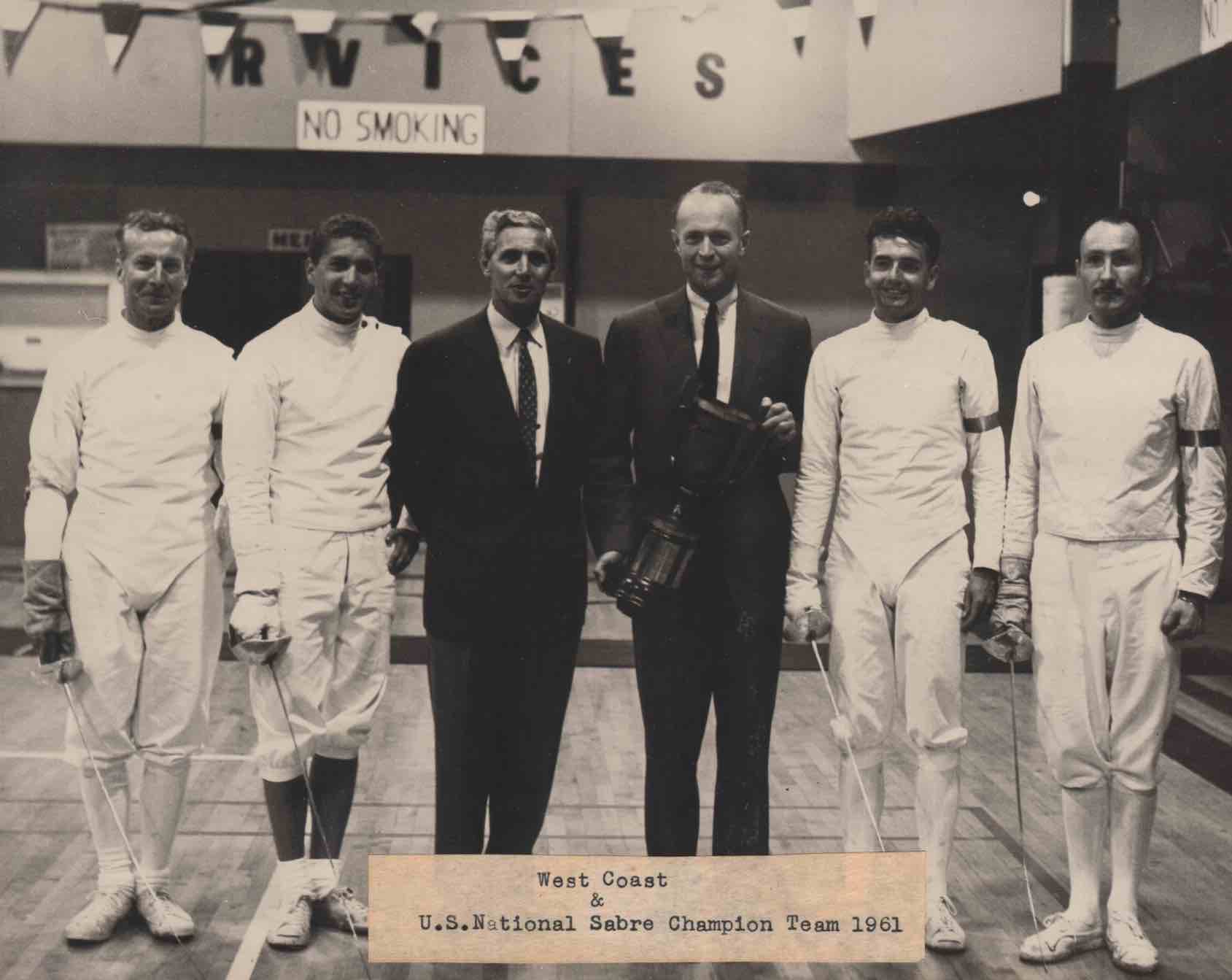

The lineup in order of placement from the 1961 Nationals. From left: Dan Magay, Eugene Hamori, Helmut Resch (an Austrian Olympic team member), George (Jerzy) Twardokens (a Polish fencer who defected to the US during the 1958 World Championships where he took the individual bronze), Ed Richards, Csaba Pallaghy, Laszlo Pongo, Alex Orban and August Witt.

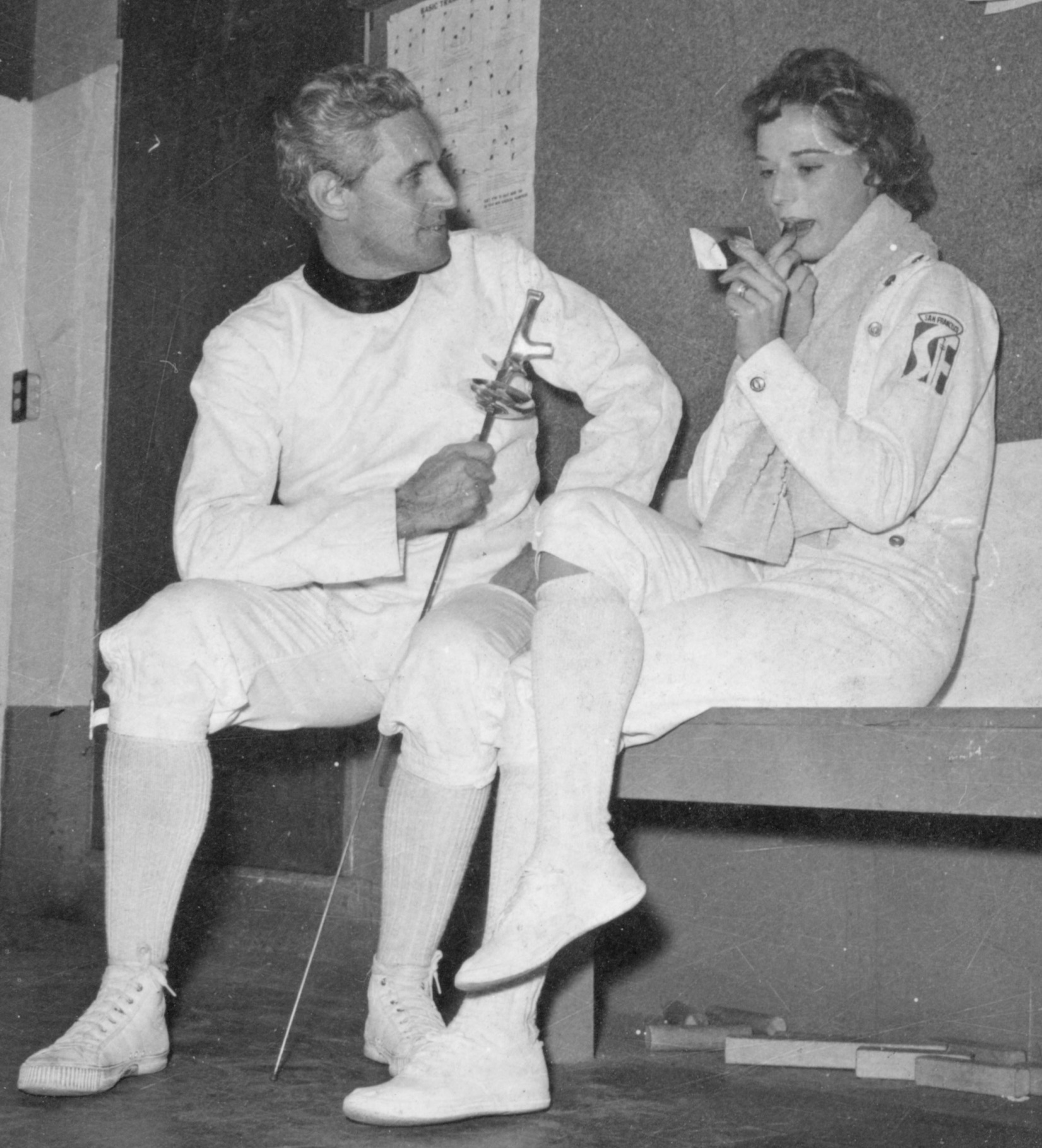

Dan led his Pannonia sabre team to victory at Nationals, as well. From left, Jack Baker, Alex Orban, Julius Palffy-Alpar, William Thiringer (Pannonia club president), Dan Magay, Gerard Biagini. This picture also showed up in last week’s story about Julius Palffy-Alpar!

By 1964 all the Hungarians who defected in 1956 had become American citizens and Olympic rules had been amended to allow an athlete to compete under a second flag. (Rule 41 of the Olympic Charter states that the only stipulation for changing nationalities for Olympic representation is a 3-year period between representing one nation and another. I can’t find when this rule was adopted but it was in between the ’60 and ’64 Olympiads.) Consequently, Magay, Hamori and Keresztes were all eligible to represent the US, along with other new citizens Orley and Orban and several others. The qualifying path to the Olympics had an additional piece as well. National results and an Olympic Trial would both factor in, along with some carryover points from the previous year. However, because rules hadn’t initially been clear (or understood by the fencers), some athletes chose not to compete much in the year prior to the Olympic season. Here’s where it’s interesting: several fencers were granted points for previous years based on their 1964 Nationals result. An estimate of what points they may have won the previous season – when they didn’t compete – were granted. At least, I’m pretty sure that’s how it was all managed. More than 50 years on, it’s all a little blurry. Magay finished Nationals in 8th place. The top four were Keresztes, Hamori, Al Morales and Orley. The Olympic Trials were held just one week after Nationals at the New York World’s Fair. This time, Magay took first place following a fence-off with Robert Blum.

It’s all very confusing as to who got what points for when and how it all added up. The long and short of it was this: Magay was First Alternate, just missing his second Olympic Games. (D’Asaro was Second Alternate.) Former Hungarian Olympic teammates Hamori and Keresztes were both selected, alongside Orley and Morales. The San Francisco Chronicle had an interesting write up about Magay’s situation. It seems he at one point considered legal action to force a reevaluation of the points system and a recount. He wasn’t the only one who thought something might be amiss. In the long run, he dropped the matter. I will say this; I do not believe there was an agenda against Magay or anyone else, although the US was certainly motivated to get the excellent former Hungarians onto the team. In fact, 1964 was the very first time the Olympic team had been selected based entirely on a results-based points system. Maybe there were some issues with it but Dr. Paul Makler, then president of the AFLA and the instigator behind the points system over “selection by committee” which was the previous standard, is a man of great integrity who I respect very highly. If he says they did their best to make it fair – and in an interview he told me exactly that – I believe him.

A news article featuring Ferenc Marki and Dan. Marki was Magay’s coach in Szeged, Hungary and again at Pannonia. Ferenc’s daughter told me that when the family learned that Dan had defected from Melbourne during the Olympic Games, her father said, “Well, that’s it then.” Dan not coming back was the determining factor in his decision to take the family out of Hungary. They went first to Italy, then Brazil. Dan made contact with him in Brazil to ask if he would take over at Pannonia upon the death of George Piller. Marki, followed soon after by his family, moved to San Francisco.

Dan fenced in just one more Nationals, skipping 1965, and in 1966 took second in a 4-way tie. Morales finished the 8-man final 6-1, then Magay, D’Asaro, Orban and Hamori were all knotted at 4-3. Magay took the silver medal on indicators. After that Nationals, Dan felt he had done everything he was capable of in the sport. At age 34, he could only look forward to his skill and stamina deteriorating over time and seeing his results drop accordingly. On the other hand, his newfound love of skiing was something he felt he could only get better at. He stepped away from the sport of fencing from that time on.

It’s noteworthy to me that in Magay’s last National final of 1966, of the men Dan competed against, six of the eight finalists are in the US Fencing Hall of Fame as Fencers. Morales, D’Asaro, Orban, Hamori, Blum and Ed Richards are all HOF fencers. And only one, Alex Orban, won more US individual titles than Dan’s three. Csaba Pallaghy was the other finalist, and while he may not have been a Hall of Fame fencer, which could be debated, he was an extremely capable administrator and worked tirelessly for fencing for decades following his competitive career. But Dan Magay was for many years the top fencer in that crowded field of exceptional competitors, an example of excellence that others aspired to.

Having stepped away entirely from the sport, his memory hasn’t been maintained through interaction with the current generation of fencers. But if we evaluate someone’s right of inclusion in the Hall of Fame based on familiarity, we’ll soon lose track to those who were standard bearers for our sport in years past. I’ll offer up one more quote from a fencing contemporary of Magay’s. Harriet King, four-time Olympian, four-time US National Champion women’s foilist and member of the US Fencing Hall of Fame, emailed me this: “Danny was a graceful stylist and powerful sabreur who was the epitome of a gentleman as well.”

In closing, if I’m not jogging your memory about a great fencer, perhaps I’m creating a new one. Here’s to you, Dan Magay. You were one of the finest fencers of your generation and you’ll get my vote.

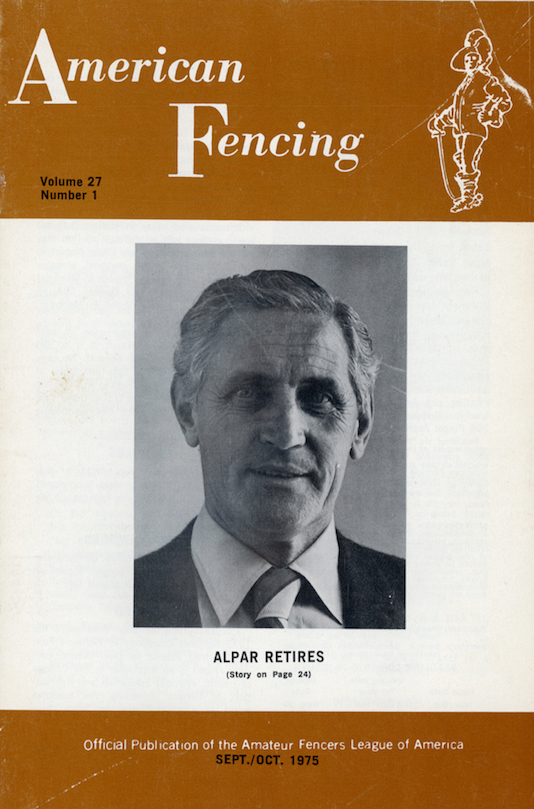

Alpar Comes to San Francisco

Some months ago, I paid a visit to UC Berkeley’s Bancroft Library to look at a collection of scrapbooks donated to the library upon the passing of long-time Cal fencing master Julius Palffy-Alpar. Harold Hayes of the Pacific Fencing Club had told me of their existence and agreed to meet me there to get a look at the books. He’d actually seen them before, as he had visited Alpar at his home in years past. I’m sad to report that I can’t share any of the photos I took of the scrapbook pages – which was ok’d by library staff. Sharing those photos on the internets? Not so much.

However, I can share what I learned. The scrapbooks contained lots of photos from various periods of Alpar’s life as you’d expect, but also some rather newsy articles clipped from papers that gave me some hints on both his early life, how he spent his time during and just after World War Two, as well as some particulars about how he came to the West.

Julius Palffy-Alpar’s main coach at the Toldi-Miklos school in Hungary was Alfred Geller, above.

Born in 1908, Alpar was a military man and officer in the Hungarian Army. He was trained at the prestigious Toldi-Miklos military school under Alfred Geller. Alpar married and performed his military service while teaching at a couple of Budapest clubs, HTVK and MAC. He was at the 1936 Olympic Games as a ‘trainer’ for the team, a possible distinction from ‘coach’, but I’m not certain. Alpar was known for his fitness and conditioning, so he may have been less fencing coach than what we would think of today as a physical therapist or trainer, but this is speculation on my part as I haven’t been able to confirm his specific role with the 1936 team.

Near the end of World War Two, Alpar’s unit was captured by the Americans which ensured them a much better fate than being captured by the Soviets. Alpar, as an officer and trained fencing master, was sent post-war to a German mountain lake that served as an R&R hub for American officers and families. There, he was assigned the task of instructor for about 15 different sporting activities including all sorts of water skiing. There are pictures of his skiing groups doing pyramid stacks, jumps and other tricks and everyone is smiling like they’re having the time of their lives. They probably were. And here’s the thing that struck me in looking at pictures of Alpar by the lake. That dude was in shape. Like, Jack LaLanne shape. (Jack LaLanne help for the youngsters.) Like, “I’ve never, ever been in that kind of shape” shape. Oh, and tan.

He worked for the US Military for about 30 months and in late 1948 or early 1949 he and his wife got on the Cunard ship Scythia and emigrated to Canada, settling in Toronto. Once established, he taught fencing at the University of Toronto, won trick riding awards at water skiing competitions and life was good.

Evidence of Alpar’s success in Canada. He’s shown here on the left with Canadian fencer Joseph Vidz (or Vida. One source says “Joe Vida was 7 time National Sabre Champion of Canada.” I can’t find any Canadian fencing history site to confirm this. I did find a “Joseph Vidz” listed as a member of the Bronze medal winning Canadian sabre team at the 1959 Pan American Games. Anyway, Alpar is on the left above.)

Sometime in 1960, he received a letter from one John McDougall. John might best be described as a ‘serial fencing entrepreneur’, due to his habit of starting clubs and businesses. He founded American Fencers Supply after learning the fencing equipment business from Hans Halberstadt, started something like five clubs and taught at several more. That’s not counting keeping Halberstadt open after Hans’ death, nor being the first person to hire both Charlie Selberg and Michael D’Asaro as fencing coaches. As it happens, John is also the person who lured Alpar away from Canada to the United States.

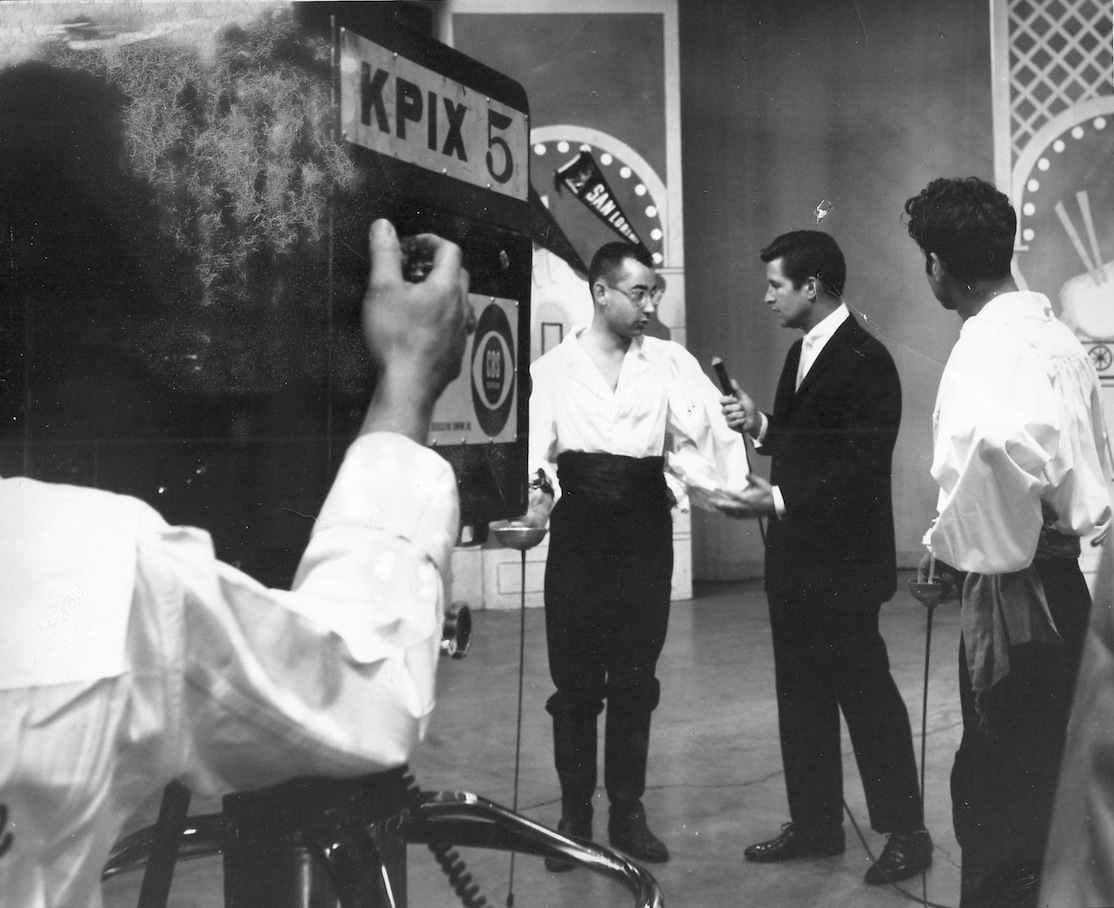

John McDougall getting air time on San Francisco’s KPIX-TV. This dates to 1958 or early 1959, shortly after the founding of the San Francisco School of Fencing and prior to John beginning his lessons on ‘how to be a hippie’ from Michael D’Asaro.

John opened the San Francisco School of Fencing in 1958. He had graduated from Stanford and worked as an assistant to Hans Halberstadt before opening SFSF. He had a grand plan for the place. Not just fencing instruction but judo, trampoline, swimming and dance. After teaching fencing for about a year, he hired a couple of assistants; Jack Nottingham and Charlie Selberg. Nottingham had been teaching up in the Portland area, but had some sort of falling out with – it would appear – just about everyone in the Oregon Division, so he was looking for work. Charlie had just graduated from SF State. John was also giving Charlie lessons but upon the arrival of Jack, turned Charlie over to him. Things went on for awhile like this until John had a falling out with Jack. Then Charlie got a job teaching art at a High School near Redwood City, leaving John back at square one as the fencing teacher.

Julius Palffy-Alpar

Somehow or other, John learned about Alpar in Toronto and in 1960, sent off a letter. In the interim, he’d changed the name of the club from the San Francisco School of Fencing to the San Francisco Sports Academy. John made Julius an offer, Julius accepted and moved to San Francisco, site unseen. John told me that he saw Julius drive by the front of the club the day before he was scheduled to start but didn’t stop in. Figured he was either scoping the place out or wondering if he’d made a huge mistake. Regardless, they went to work and John’s publicity department (himself) went to work. Many of the articles I have that are related to the SFSF/SFSA came from the pages of Hans Halberstadt’s personal scrapbooks.

Alpar with author Diantha Warfel. There is a series of photos with these two and somewhere along the line I was either told or assumed that the woman was the President of UC Berkeley. Wrong. Diantha wrote a teen novel about the exciting sport of fencing, published in 1961. You can find an old copy at a range of pricepoints on abebooks.com. She was married to the longtime General Director of the San Francisco Opera, Kurt Adler.

Alpar brought a new energy to the SFSA and if the photos tell the truth, seemed to be having a good time.

Alpar with Roberta McDougall, John’s first wife. She’s sporting an excellent SFSF patch that I currently have zero examples of in my collection.

I have to assume that he also did a little moonlighting at Pannonia AC, as he is pictured with the National Sabre Team Champions of 1961.

L-R: Jack Baker, Alex Orban, Julius Palffy-Alpar, William Thiringer (President of the Pannonia Athletic Club), Daniel Magay and Gerard Biagini

Whatever was going right for Alpar in San Francisco, in 1962 he received an offer too good to refuse that took him out of The City. UC Berkeley, that school with the on-again, off-again relationship with fencing, had briefly been the employer of George Piller until his passing in 1960. They extended an offer to Alpar who, in turn, had to break his contract with John McDougall and the San Francisco Sports Academy. John had sponsored Alpar’s visa with the US Government and felt indebted to John. But Berkeley would certainly improve his status as a coach and, more realistically, pay a good deal more. John, with his usual kindness and humanity, recognized what a good opportunity this was for Julius and graciously let him out of his contract.

A group of UC Berkeley fencers pose with Alpar in 1967. Look two heads to the right over from Alpar and you’ll see the future US National Sabre Champion of 1978, Stanley Lekach.

From 1962 on, Alpar kept Berkeley infused with fencing instruction without a break until he retired in 1975. During that time, he not only taught classes but choreographed fight scenes in plays, made a film about his work teaching fencing to the blind, wrote his book “Sword and Masque”, and gave lessons to the famous mime Marcel Marceau. His tenure at Cal may well be the longest stretch any fencing coach ever had in the way of a straight run. For whatever reason, it seems anytime they need to drop a program or monkey with budgets, the fencing teacher draws the short straw. It’s been like that since the 1920s. But Alpar seems to have beaten the odds.

One of these days I’m going to head back over to the UC Berkeley library and see if I can find someone who may be willing to let me write a post using some of the photos out of the Alpar scrapbooks. There are some truly wonderful pictures of him, his wife and their many friends and compatriots from Hungary, Canada and the US. I’d love for you all to see the photo of Alpar sitting on a bench near the shores of that German lake, swim trunks, no shirt, smiling and tan and totally cut from all the waterskiing. Having the time of his life.

Connections

I remember James Burke’s late 70’s TV series very fondly but haven’t watched an episode in a very long time. I wonder if it holds up? Burke, in my memory of the show, had a unique ability to trace the origin of modern technology back to inventions from ages past, noting how seemingly insignificant developments in one area would lead to the next leap forward somewhere else. A recently-made connection to the family of Los Angeles Athletic Club fencer Andrew Boyd got me thinking about it.

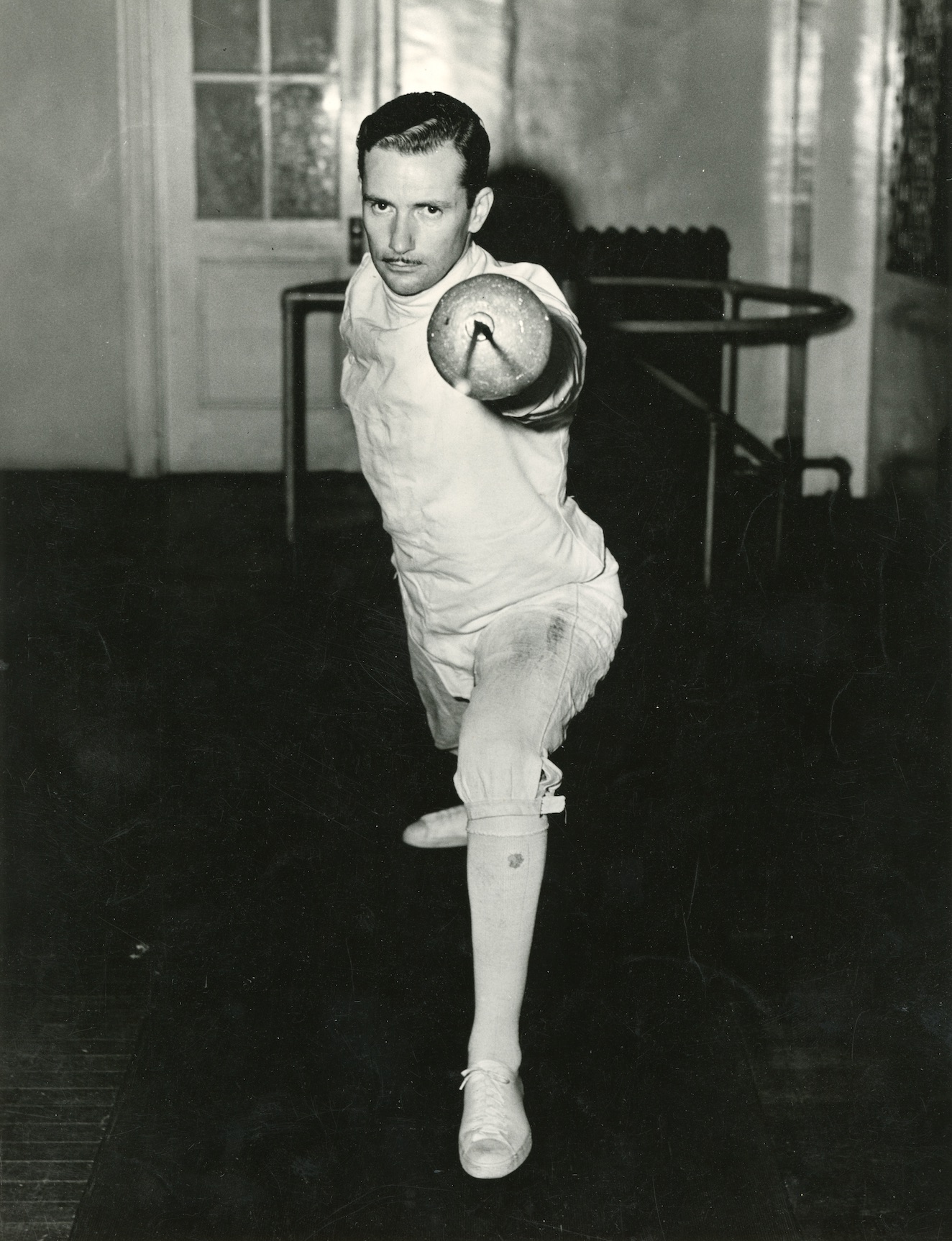

Andrew Boyd in an undated photo. Likely from 1936.

Andrew Boyd was a fencer I have wanted to know more about for quite some time now. His name appears regularly in tournament results dating back to the early 1930s and continued until the early 1960s. His teacher was the great – and I’m getting more and more information to back up that pronouncement – Henri J. Uyttenhove, long-time Los Angeles Athletic Club Maestro, to say nothing of his teaching at the Hollywood Athletic Club, The Pasadena Athletic Club, USC, UCLA and his own private club in Pasadena. I wonder how he got around so much? The Arroyo Seco Parkway, now the 110 freeway, didn’t open until 1940 and Uyttenhove started his Pasadena Club and his gig at the LAAC around 1910. It’s entirely reasonable to imagine that he traveled throughout Los Angeles County on the Red Car, a fabulous mass transit system now mostly remembered as a featured element in the plot of “Who Framed Roger Rabbit”.

Andy Shaw at the Museum of American Fencing had a couple of pictures of Andrew Boyd and a little bit of information. There is also data to be mined by perusing back issues of American Fencing Magazine for tournament results. It’s there I learned that Boyd was still making the semi-finals at Nationals until 1961 – at 51 years of age. It’s a little more challenging getting results from the 1930s. American Fencing Magazine didn’t begin publication until 1948 and finding old copies of The Riposte Magazine or the AFLA Secretary’s Newsletter are even more challenging to track down. Another good resource is one I’ve mentioned several times in past writings, The Fencer magazine, but its short run gives it a limited range of usefulness. With one thing and another, I’ve been able to glean quite a bit of info on Mr. Boyd and his competitive successes. I also knew when he was born and when he passed away, but nothing else.

While trying to find out more about Boyd, I hit upon the idea of sending an email to the city clerk of his former town, which I found on Wikipedia. I got an email back right away from the clerk who didn’t know anything helpful for my search but knew someone who might. Later that same day, I received an email from Andy Boyd – the son of Andrew Boyd the fencer! Can I just say, I love small towns. Everybody knows somebody who knows everybody.

After a series of back and forth emails, I determined to take a drive over the mountains – through Yosemite, actually – to the Owens Valley and meet the Boyds. Come to find out, Andrew the elder had several children and grandchildren who were all well-versed in the story of their Olympian family member. Andy had a weapons bag, photos, news clippings, trophies, even a home-made scoring machine, although the wires have now been pirated for some other project. They allowed me to scan and photograph to my heart’s content and now I can share some of the story and other highlights from my visit.

Andrew Boyd’s homemade scoring machine for epee. Note the two lightbulb sockets on the top. At a guess, I’d say the doorbell buttons must have been rigged to ring the bell at the same time the lights fired. (“Is someone at the door?” “No, I’ve hit you in the elbow!”) Probably not the most sophisticated scoring box ever made, but it probably came in handy in 1935 or thereabouts when official devices were scarce.

Boyd was selected to the 1936 Olympic team and was the only SoCal representative on that team. Based on other research I’d done I had to wonder why he was the only Westerner on the team, so I did some digging.

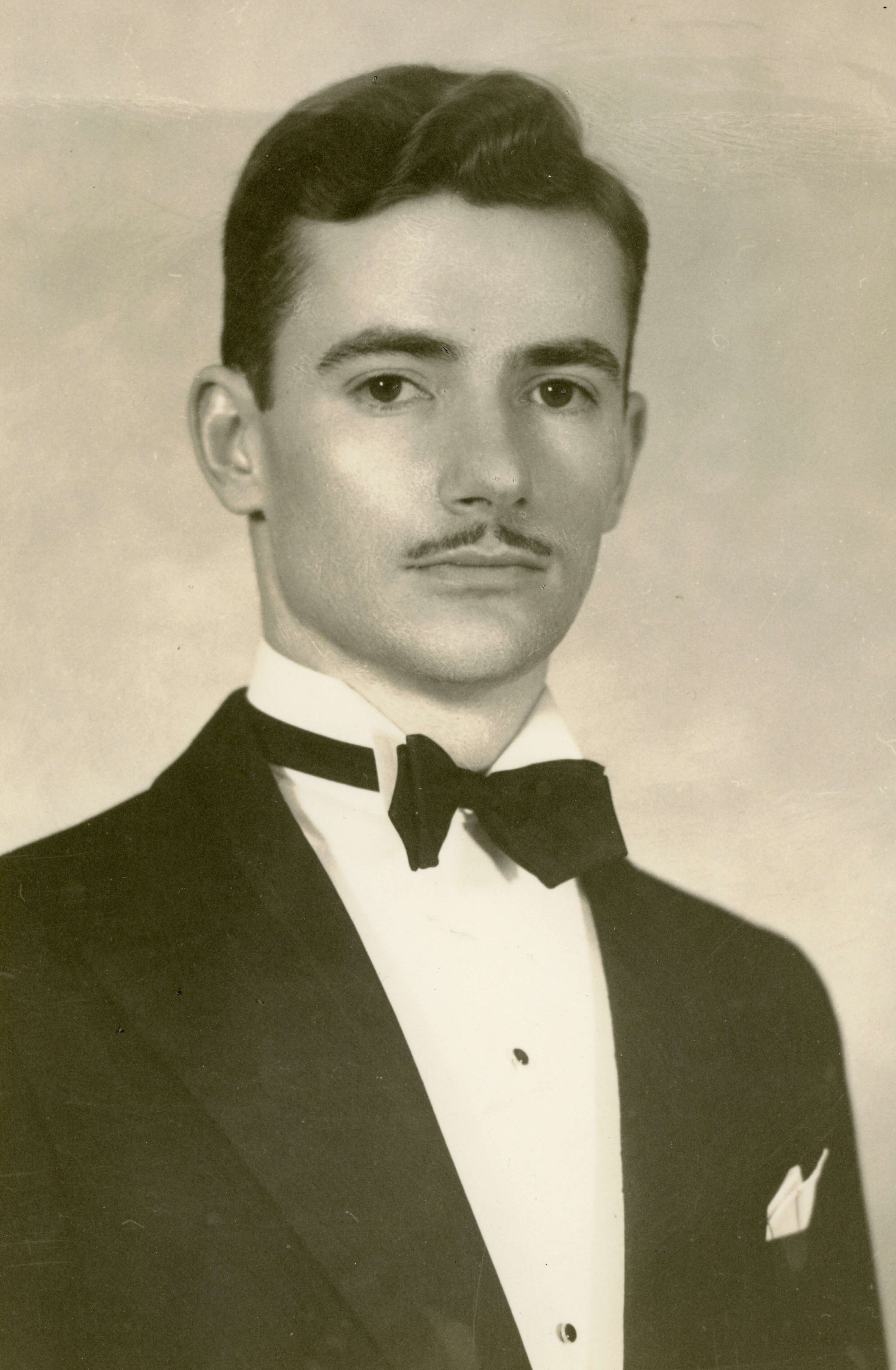

Andrew Boyd, 1936

Let’s talk politics. No, not today politics. Ancient fencing politics. Back in the days of yore, the East Coast hegemony ran things. That’s just how it was. They founded the organization, they made the decisions. Now, the Pacific Coast section was the largest section outside of Metropolitan New York. Both the Nor Cal and the So Cal divisions had good numbers of members back in the 1920s and 1930s. However, when it came time to do things like, oh, you know, choose the members of the Olympic Team, let’s just say the West Coast contingent didn’t get much consideration from the selection committee who, need I mention, were all from New York and mostly from the NYAC. This caused no small amount of frustration for folks who fenced at places other than the New York Athletic Club. This bubbled over in the lead up to the 1928 Olympics. The West had some pretty good fencers, but the New York powerbrokers didn’t really imagine giving up Olympic spots to West Coasters in place of their friends & teammates. After the ’28 Olympics, to quiet the hubbub the New Yorkers decided to settle the matter on the strip. They put a bunch of their best fencers on a train headed west and challenged the noisy Californians to put up or shut up. The results ended in a decidedly different manner than the New York contingent expected. Only one fencer from the East, sabreman and famed photographer Nick Muray, went home with a medal, and it wasn’t gold. Having demonstrated their mettle, the West was granted a path to the Olympics. The top finisher in each weapon at the Pacific Coast Championships would be granted a spot on the team. This upped the ante for PCC participants, to say the least. And in 1932, this led to the inclusion of the top West Coast talent: Hal Corbin epee, Ralph Faulkner, sabre, Ted Lorber, foil.

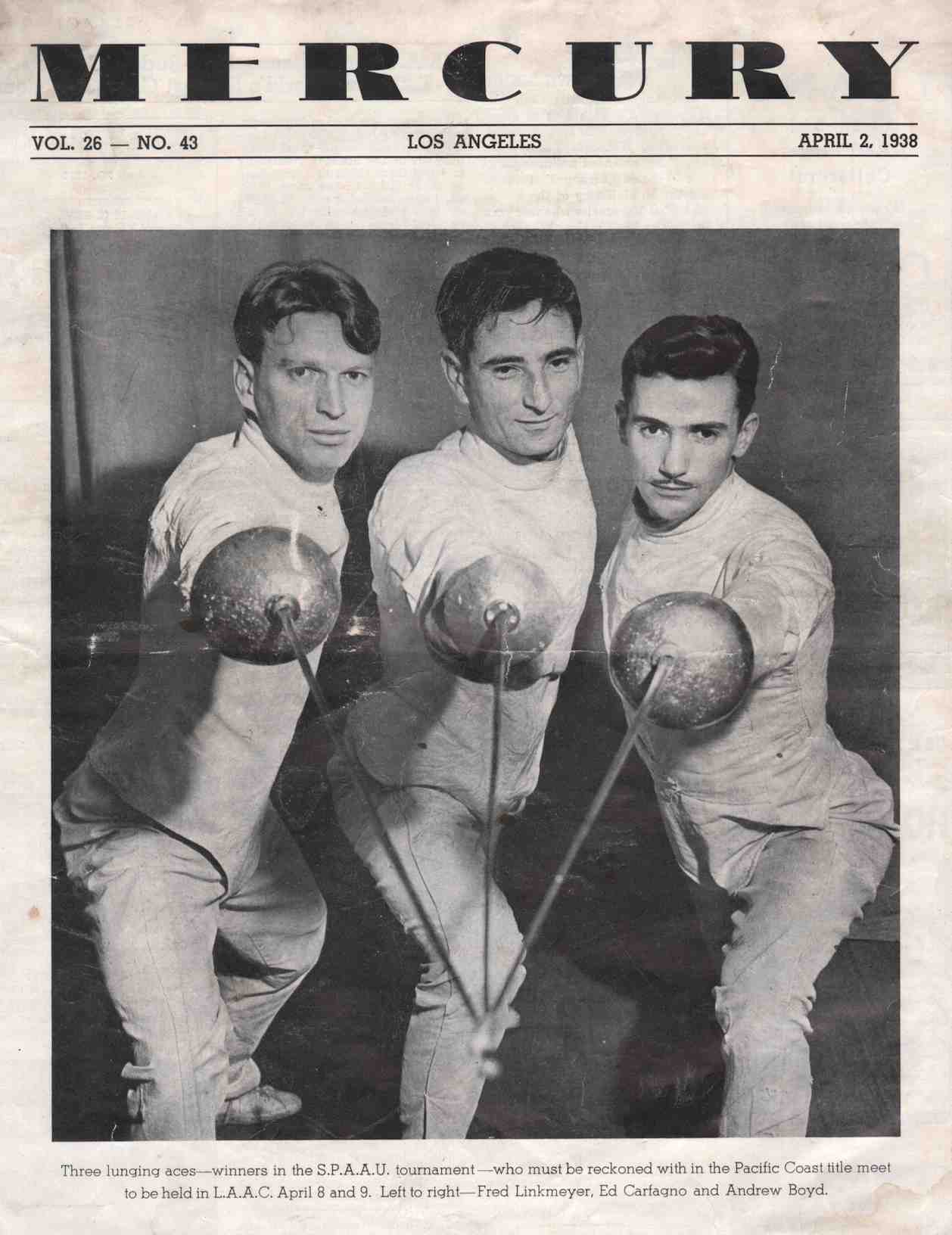

Fred Linkmeyer, Ed Carfagno and Andrew Boyd. Carfagno won the Silver medal in foil at the Nationals in 1939, the year after this was taken. Like Boyd, he was a likely candidate for the cancelled 1940 Olympics.

For reasons lost or obscure, this set of rules were altered slightly for the selection of the 1936 team. Only one West Coast fencer was picked for the Berlin Olympics. Andrew Boyd. In reading some news articles from the period, it seems that the New Yorkers added a new wrinkle to qualifying for the Olympic berths. That wrinkle was to require attendance at pre-Olympic training sessions and competitions to prove yourself worthy of consideration. And guess where all the training and competitions were held? If you guessed anywhere other than Metro NY, go back three spaces. Ostensibly, this was to ensure that the selected fencers would be in good training and top form for the Games. That notion is commendable, of course. But in practical terms, it meant anyone with the credentials to compete had to be in New York for an extended period of time, a challenging requirement for people living and working anywhere other than New York. However, Andrew Boyd was able to ‘beat the system’ as it were. He was working at that time for a company with a New York office. When he informed them that he had a chance for making the Olympic team but needed to be in New York to compete and train, they transferred him to New York. That put him in the right spot to not only get in on the training and competition, but also get to know the ins and outs of the New York crew. When the penultimate selection competition came around, the US Nationals in 1936 – in New York – he finished in 3rd place, securing his spot on the team.

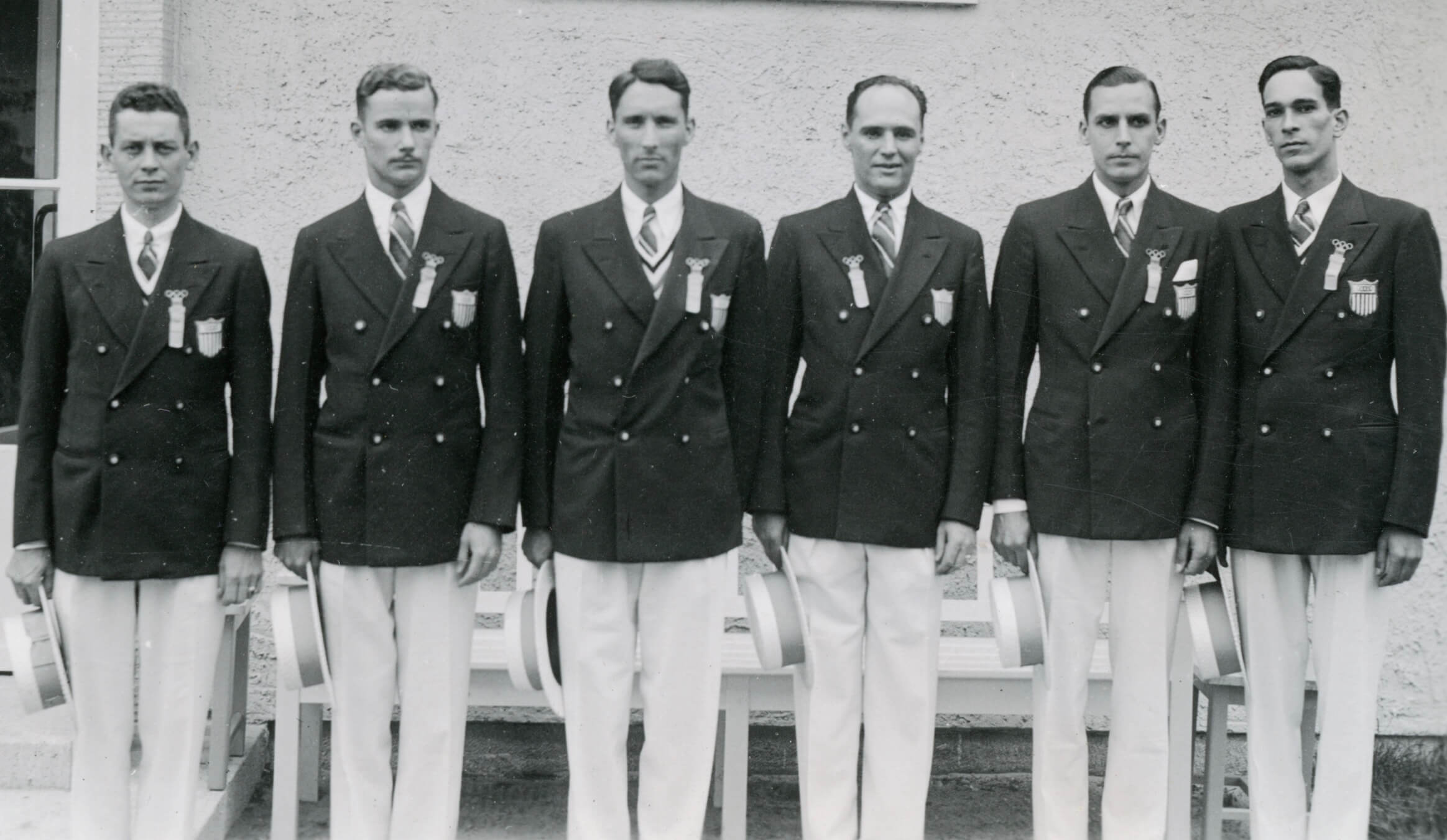

Left to Right: Thomas Sands, Andrew Boyd, Gustave Heiss, Frank Righeimer, Tracy Jaeckel, Joe de Capriles. These six made up the 1936 Men’s Epee team. Not pictured is Frederick Weber, a member of the modern pentathlon team and a top epeeist who, along with Heiss and Righeimer, fenced in the Individual epee event but not the team event.

But if you imagine that to be the end of the politics, think again. At the Olympic Games, he was kept out of the individual event by the choice of the captain following a vote among the team members. For the team event, they started without using Boyd until they faced Sweden in the semi-finals – a match the US didn’t have much hope of winning. (The Swedes went on to beat France for the Silver medal.) Boyd was thrown in for his first Olympic matches and promptly won two bouts and tied a third, giving him the best record for the US in the match. The US went down 7 wins to 8 for the Swedes, Boyd’s tie match counting as a null or half-victory. A shortened Olympic experience for Boyd but one wherein he proved he could stand up against anyone.

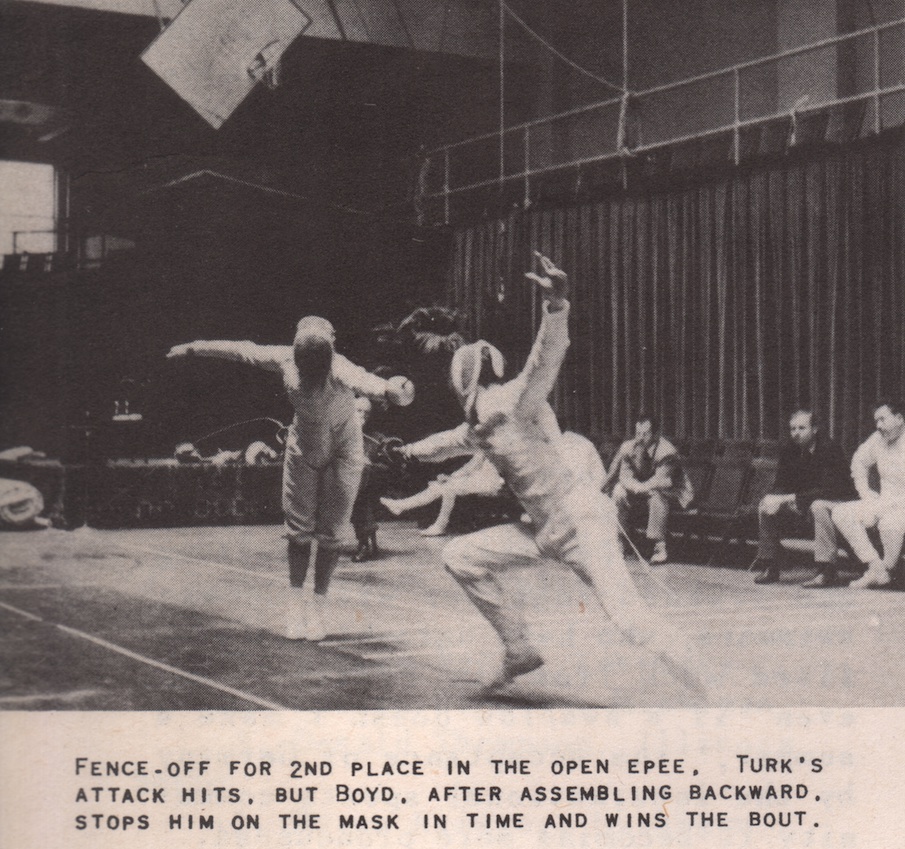

From The Fencer magazine.

Andrew’s early days of fencing are obscured by the years, but the family tells the story of how his mother didn’t care for him running track due to an abundance of caution concerning his health. Remember that this was a time when running in a marathon was, in the view of some, a life-threatening undertaking. How fencing became the safer alternative, sadly, we’ll never know. Uyttenhove was his coach from the beginning, likely at the Los Angeles Athletic club, although it’s possible Uyttenhove still maintained his salle in Pasadena which he opened sometime around 1908. I have yet to find a record of when that club closed, or where it was located. The Boyd family lived in both Pasadena and Altadena and Andrew was born in 1910, so he would have likely begun fencing in the late-20s or early-30s. Andrew represented the Los Angeles Athletic Club throughout his competitive career. Located in downtown LA, the LAAC was a short Red Car ride from both Altadena or Pasadena on the Downtown line through the Arroyo Seco, then a quick transfer onto the Main Street line to 6th Street. Jump off at Olive and you’re half a block away! I have no idea how long that took. By car it’s probably a half hour with no traffic and there’s always traffic. The old maps of the Red Car line don’t indicate time for distance traveled.

After the 1936 Games, Boyd remained in contention and received several letters in the run-up to 1940. Until 1939, there was still some thought, if little hope, that there might be an Olympic Games, so sports governing bodies were continuing to pursue qualifying until the Games were officially acknowledged to be off. After the war, he continued to compete and was named to the 1948 London Olympic team.

Relaxing with the 1948 team in London. Boyd is on the far right in the Hawaiian shirt. Next to him, furthest right, is Team Captain Salvatore Giambra from San Francisco’s Olympic Club. Dernell Every is the one twisting around to look over his shoulder and 3rd from the left wearing glasses is Tibor Nyilas who helped the sabre squad to a Bronze medal.

The LAAC teams led by Boyd and long-time sallemate Fred Linkmeyer dominated the West Coast for years and Boyd’s name continued to be mentioned as a contender for many years. By the mid-1950s he wasn’t attending the Nationals every year but every now and again he’d show up for the team event, as in 1959 when he and his LAAC team took 3rd in Team Epee. He was still considered enough of a player to be named a member of the Olympic Squad prior to the selection of the 1960 team.

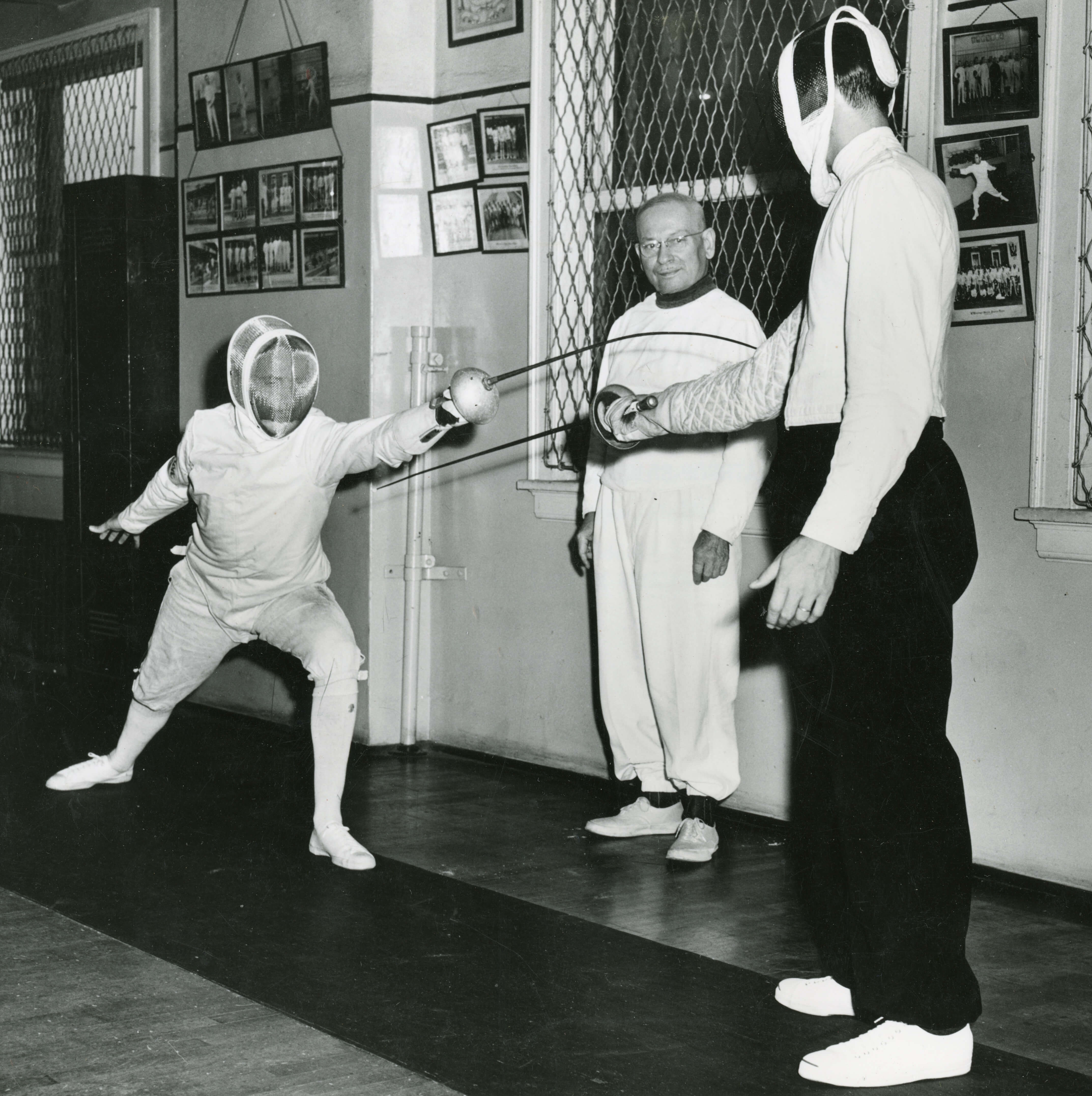

Andrew Boyd lunges and hits Fred Linkmeyer at the LAAC while Henri Uyttenhove observes.

One last story. If you’ve been following along with the Archive, you may have seen the story about Captain John Duff. (If not: here it is.) Sometime prior to leaving Southern California around 1932, Duff created two prizes for two separate tournaments to be held in his name, the Duff Epees and the Duff Foils. The epee event was for the menfolk and the Duff Foil was a women’s event. Duff had beautifully engraved matched pairs of foils and epees created as the prizes for the events, along with a very interesting stipulation. That was, whoever could win the event in three successive years would win the prizes outright. For keeps. I’m not certain when, or if, the Duff Foils were eventually awarded permanently. In fact, the foils event was the first mention I ever read about in my copy of The Fencer magazine. (The Fencer, part 1)

Here is the quote from The Fencer, October, 1946:

“The contest dates back to 1936 when Captain John Duff presented a matched pair of decorative foils as trophies for a summer women’s competition, and a similar set of dueling swords for a men’s epee event. The prizes were to be retired by any fencer winning them for three successive years. The Duff Swords were retired by Andrew Boyd of the LAAC after the first three competitions, but the Duff Foils are still being fought for.”

The dates here may be a bit off. The Boyd family was kind enough to make a donation to the Archive of some documents, and included in that packet was a note that Andrew had already taken possession of the Duff epees by 1936, having won the first three runnings of the Duff epee competition.

Now, let’s face it. There isn’t a great deal of competition for me in this realm of researching the history of fencing on the West Coast. But I’d read the above passage about the Duff epees a year or two prior to my first introduction to the Boyd family, so I knew what the Duff Swords were. At least, the knowledge floated somewhere in the not-too-distant recesses of my noggin. But when I went to visit the Boyds, one of the very first things Andy asked me was, “Now, have you heard of the Duff Swords?”

The highly engraved Duff Dueling Sword. The matched pair came with scabbards as these are sharp swords, not fencing weapons. Over time, the leather of the scabbards has worn away although the family still has all the pieces.

I don’t know how many folks today could have responded in the affirmative to that question about a fencing tournament trophy taken out of circulation around 1936. It seems that so much of what I find myself doing is reading an article or caption, maybe seeing a picture, then sometime later these disparate moments and elements wrap together giving clarity to a larger historical context. And so, I keep reading and looking at the scads of material I’ve been collecting, knowing that I can’t predict which item six months ago or six months from now might suddenly connect to another piece of the puzzle. I wonder if that’s how the TV show was created? The idea appeals to me, that’s certain. Making connections to fencing history may not pay well, but rewards are there nonetheless.

Getting to hold one of the Duff Swords? Now that was a great connection.

Never Enough Aldo Nadi

I’ve never seriously considered getting a tattoo, but maybe the title of this website entry would be the one. I can’t seem to get more than two or three entries along on this site before Aldo Nadi’s name pops up. Keeps happening. However, the motivation for today’s article comes from an external source, so let me lay blame where it truly belongs. Carl Borack, this one’s on you.

Now, I’ve been working on an article strictly about Carl’s career in the sport for quite some time. A few times I’ve tried to get my head around it so that I can do my small part in cataloging something of his truly astonishing impact on US fencing, but I have yet to get it settled into a direction I’m happy with. I’ll get there, but it’s taking longer than I usually need to shape up an article. It’s coming, Carl.

In the interim, I’ll say that I’m fortunate to be on the receiving end of frequent emails that Carl sends out to friends detailing some tidbit of fencing history. Often, they include photos of International teams that he has been on either as a competitor or as cadre, as he has many times been Team Captain or some other important position for US fencing at major competitions. The pictures included in a recent email were a bit different and it turned me on to an article I’d not previously been aware of. It’s out of Look Magazine from the 1930s. If you’re not familiar with Look, you may know about its nearest competitor, Life Magazine. They were similar in format and content. Life may have been a little more, something, maybe classy, maybe just with higher production values or a bigger budget. Life lasted longer, also. But Look is a fun source for interesting articles from days of yore, and I enjoy the marketing style from the period. Big, colorful, full page spreads advertising scotch whisky or the new model of Edsel are just fun to look at. Madison Avenue in its heyday.

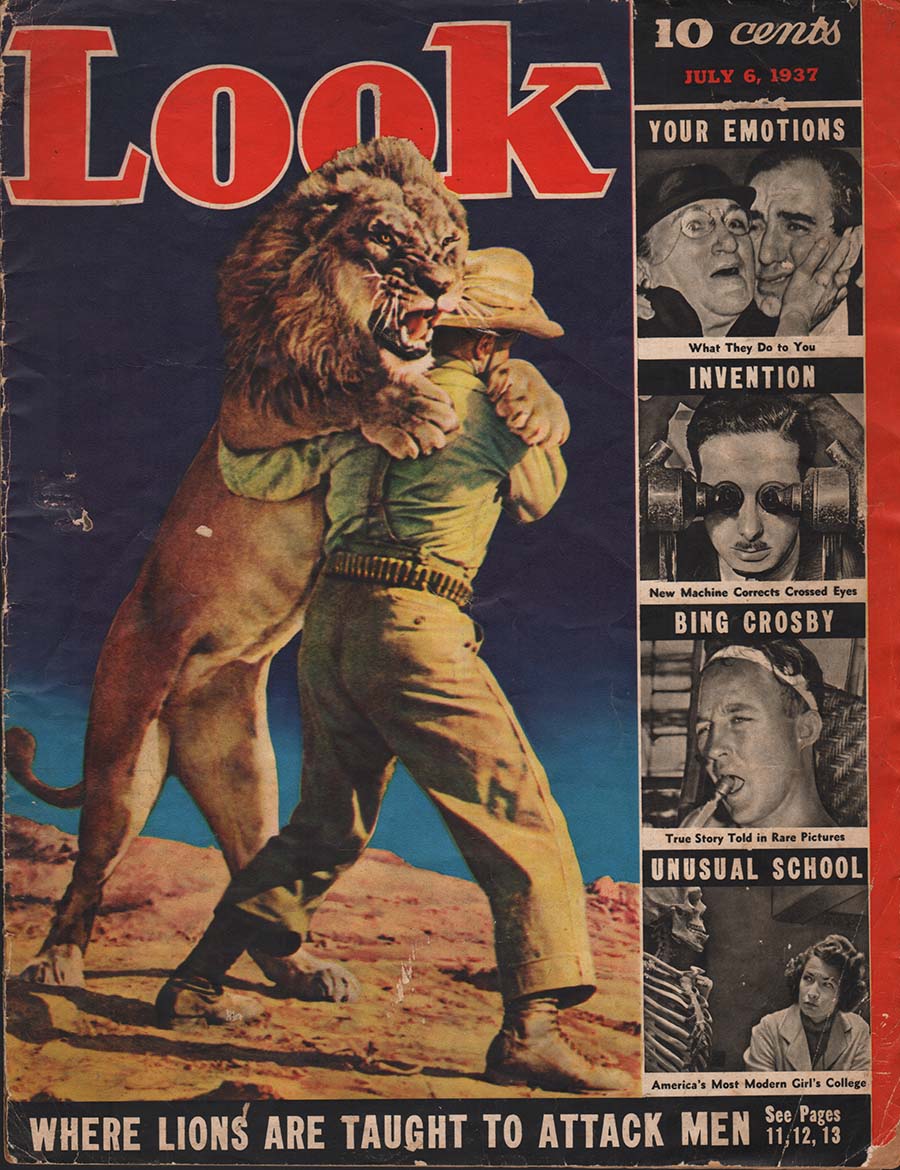

Carl sent out a couple of images under the header “Aldo Nadi – 10th publication of Look Magazine published in 1937”. He had me at “Aldo”. The images were some snapshots from a two-page spread about Maestro Nadi. Some of you reading this might not be surprised to know that after seeing Carl’s email I immediately opened a couple of new tabs on my computer – one for Wikipedia and the other for Ebay. The first was to try and track down more specifics about the 10th issue of Look Magazine. Thank you, Wikipedia, for having information like this readily available for me to glean necessary specifics to make my Ebay shopping more manageable. Armed with a publication date, I fed that into the Ebay search window and came up with a bunch of available back issues. Here’s the cover:

The July 6, 1937 edition of Look Magazine. All this could be yours for ten cents. That was then. Now? It’s a bit more.

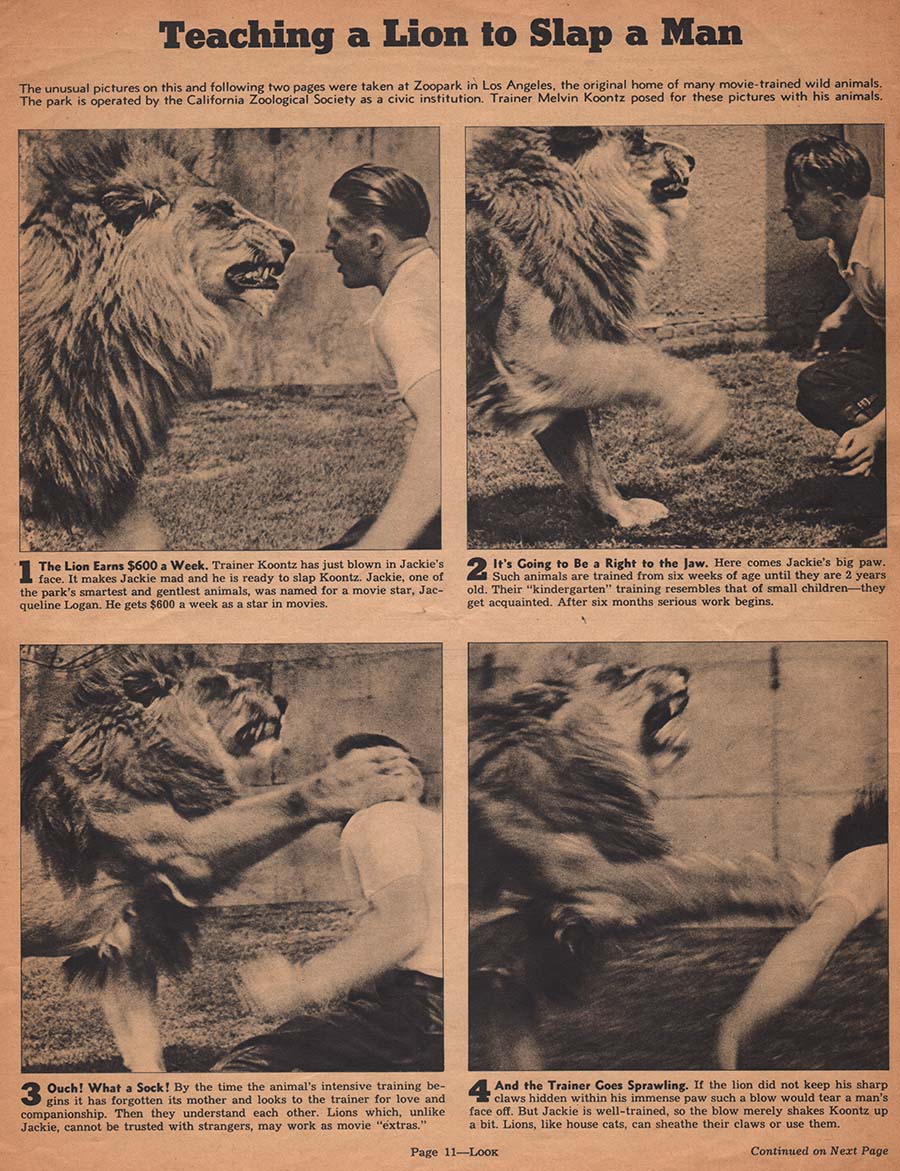

So many fun articles inside! I’d be interested to look through the pages even without a fencing-related article, but its inclusion gives me a semi-supportable justification to spend a few dollars to nab a copy for myself. After a few days of patience the mail service dutifully delivered the magazine to my doorstep and I was able to dig in. The thing that jumped out at me is that the tone of Look is decidedly different than Life Magazine. The captions and writing in Life are more formal and erudite. Or maybe they just hired better writers. Look seems to try to inject a little sensationalism onto the page with articles like this one:

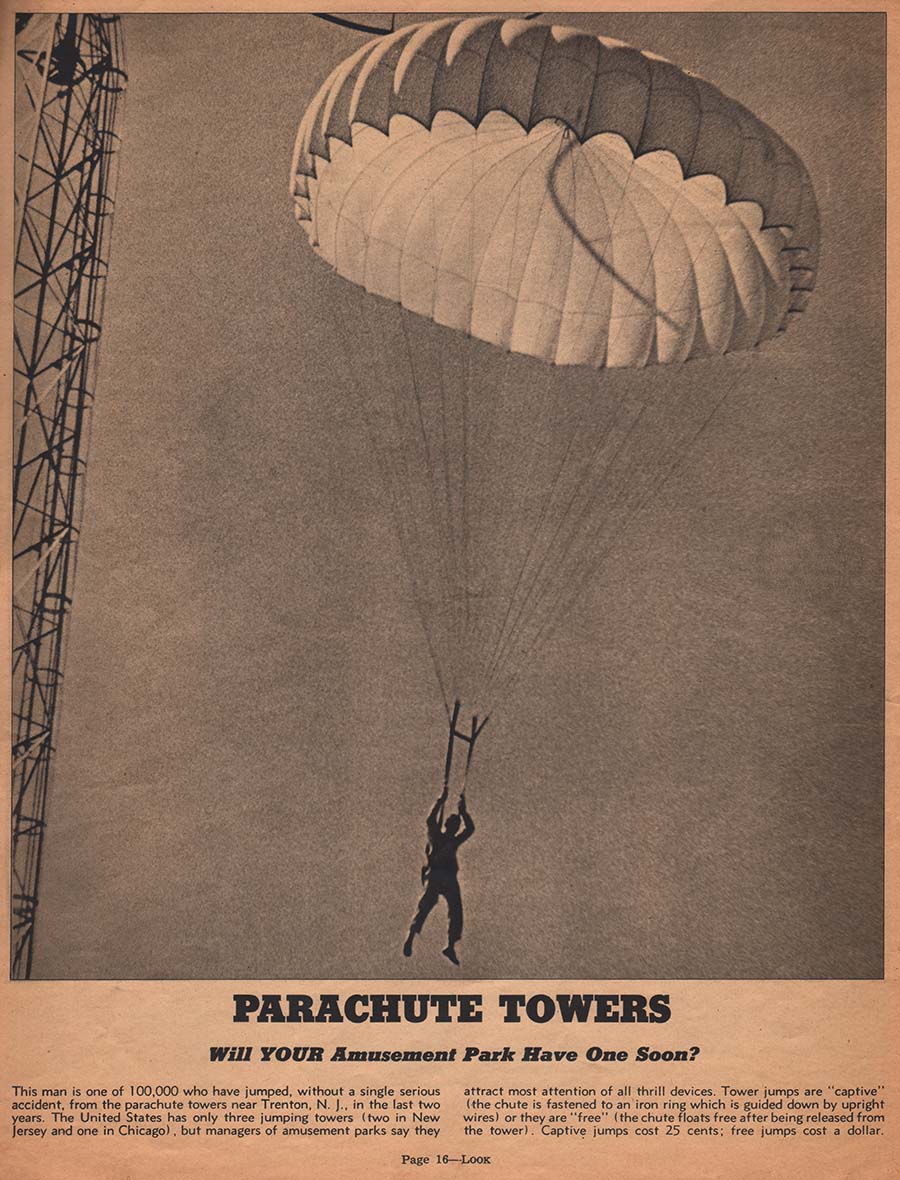

There’s another page about fighting with Tigers so they don’t bite off your arm, but I think this gives you the overall idea.

And another:

The answer to the question posed here seems to be a resounding “no” based on my experience with today’s amusement parks. How many had to die before the question was truly settled?

They’re all a bit much and fun to read in 2019. But let us stop with the beating around the bush. There’s Aldo Nadi pictures to look at!

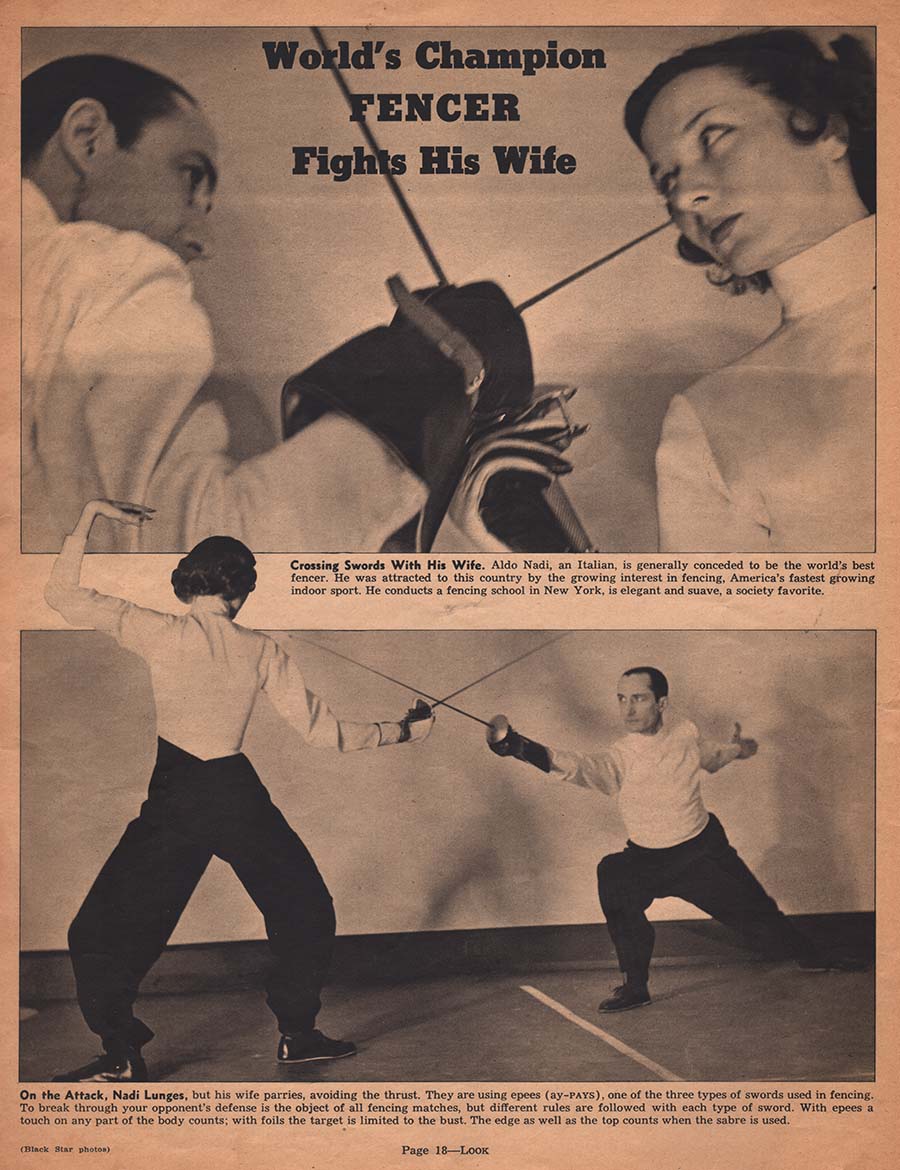

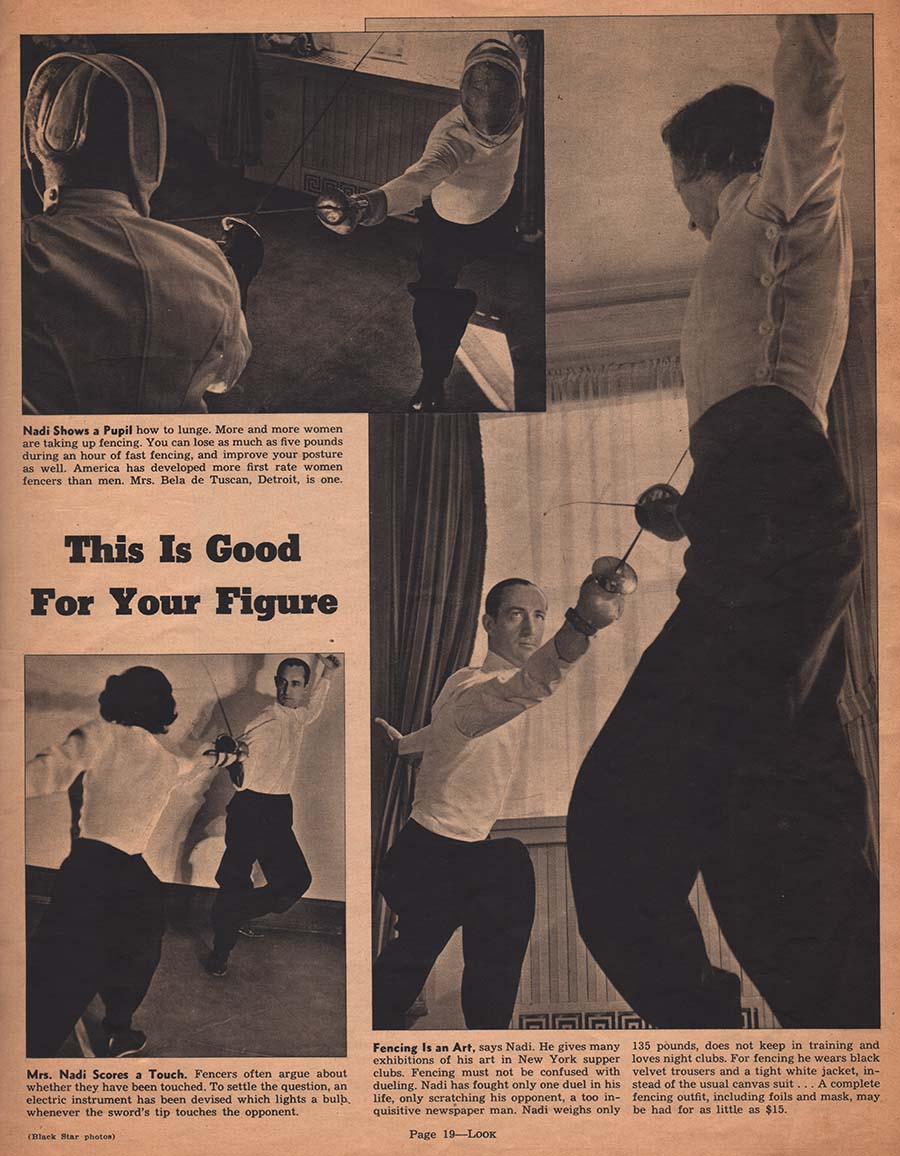

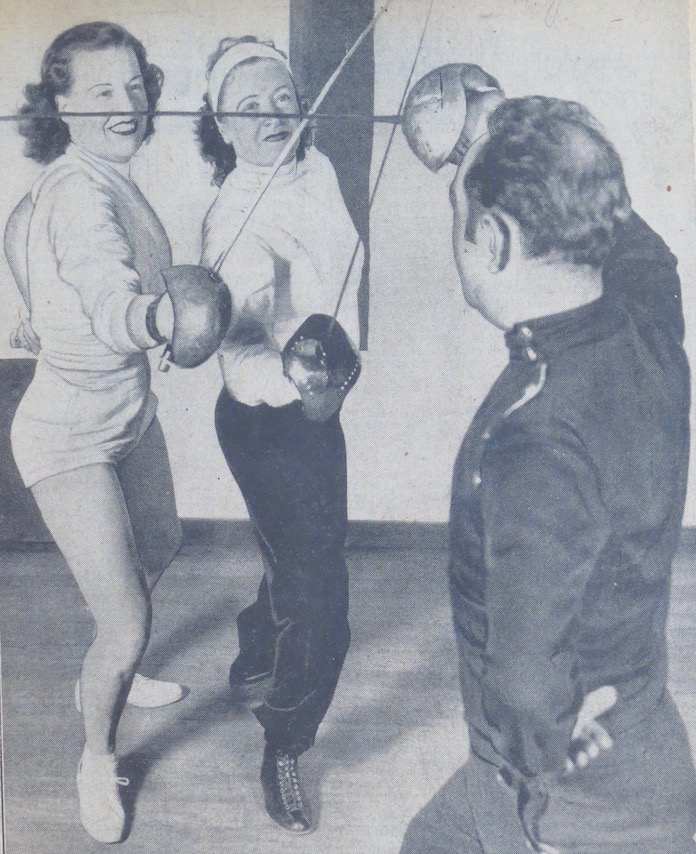

In 1937, Aldo Nadi and his wife were living in New York City and Aldo had his own salle d’armes the Aldo Nadi Studio. He’d come across the ocean at an uncertain time in Europe to make a splash in the New World. And, within carefully defined limits, he did. Not the first (nor the last) European to come to the US with the intention of turning the country into a fencing powerhouse, Nadi had the ego to imagine being the catalyst for that change but the intelligence to realize after a short time that the country was too damn big to be manageable in that way. So he settled for making what progress he could in New York and writing his book, “On Fencing”, published in 1943. But certain advantages that Nadi had in being the latest greatest European fencer to grace these western shores were his movie star good looks and a flair for publicity. That was all he needed to crack his way into a variety of articles and newsy gossip columns which kept his name and likeness to the fore. The notion of a fencer being the subject of gossip columns may seem a stretch, but Nadi arrived in the US famous and single, and moved between relationships rather fluidly among the upper class of New York until settling down with his wife, Rosemary. Perhaps ‘settling down’ is a little too definite. By many accounts, marriage didn’t entirely erode Nadi’s waywardness. Anyway, here’s page two:

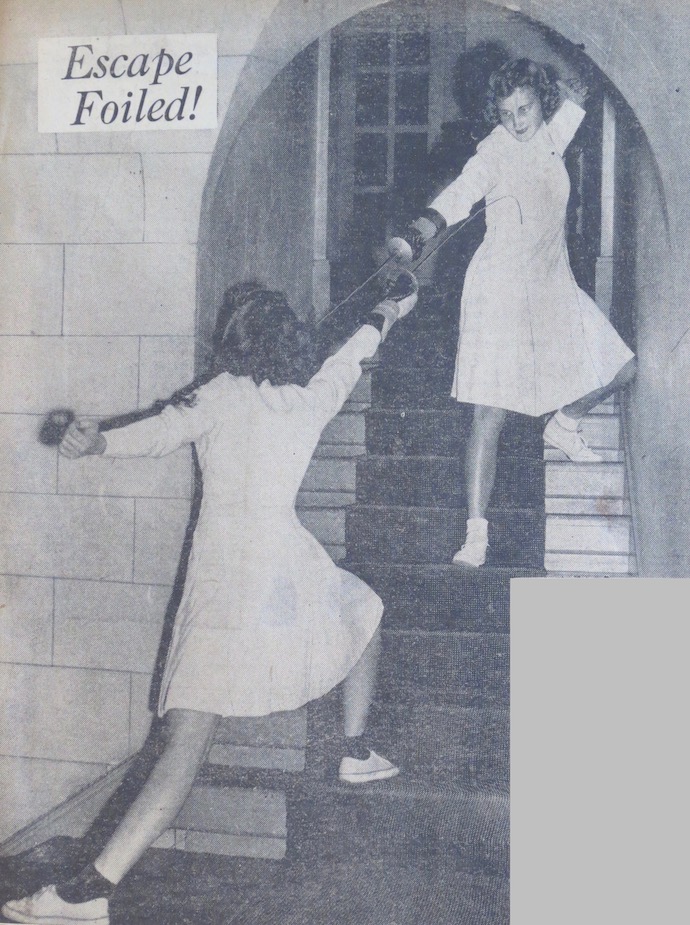

It almost reads that ‘fighting with your wife is good for your figure”, although that may not have been their intent.

Since I couldn’t resist doing a little more digging about Aldo Nadi and the publicity he attracted, here’s an article from the Minneapolis Star Tribune, Dec. 16, 1936, when Nadi was still a single fencing celebrity and attracting female companionship like handsome and dashing 1930s film stars did:

Do girls still go “all agog”? Is that still a thing? I don’t think that’s still a thing. But it does add a new take on the various titles that could be attributed to Nadi. Along with everything else, it seems he was also a “he-beauty”. Not for nothing were the ladies swooning! But Rosemary won that war and she was no slouch as a fencer herself.

My thanks to Carl for pointing me in the direction of the Look Magazine article on Aldo Nadi. Like most things that I start out on, I’ll eventually find a means to rabbit-hole down some well into topics relevant and topics not-so-much. This one seems to have a bit o’ both. But let’s end on one additional piece of cultural education from Look Magazine, circa 1937. I think we can all learn something here. Just don’t ask me what exactly we’re learning.

The First NCAA Women’s Championship

Everything has a first time and 1982 was the year of the first Women’s Foil championship for the NCAA. Held at my now-alma mater San Jose State University, thus putting me at the time in close proximity to the goings on, I remain in the dark as to why exactly the NCAA hadn’t up to that point recognized the long tradition of women’s collegiate championships. Like so many things related to women’s sport, I have to assume that Title IX was the change agent and not some ‘I see the light’ moment on the part of NCAA officialdom.

The Official Bumper Sticker of the 1982 Women’s NCAA Fencing Championship. How this survived in my possession from back then to today is utterly beyond me.

The National Intercollegiate Women’s Fencing Association – like everyone, let’s call it the NIWFA to save my fingers – had held a women’s event since its founding in 1929. For many years that was THE women’s championship. Sometime after Title IX was put in place to attempt a leveling of the playing field for sports and, according to Wikipedia, in an effort to usurp the place of the AIAW (Association for Intercollegiate Athletics for Women), the NCAA created 12 new women’s championship events for the 1981-82 season and fencing was among the new events. Not surprisingly, the NCAA, in short order, vacuumed up all the AIAW’s championships for themselves.

The program cover with a drawing by Ian Sandiland, an SJSU fencer who did graphic art and excellent silkscreened t-shirts for many a local tournament.

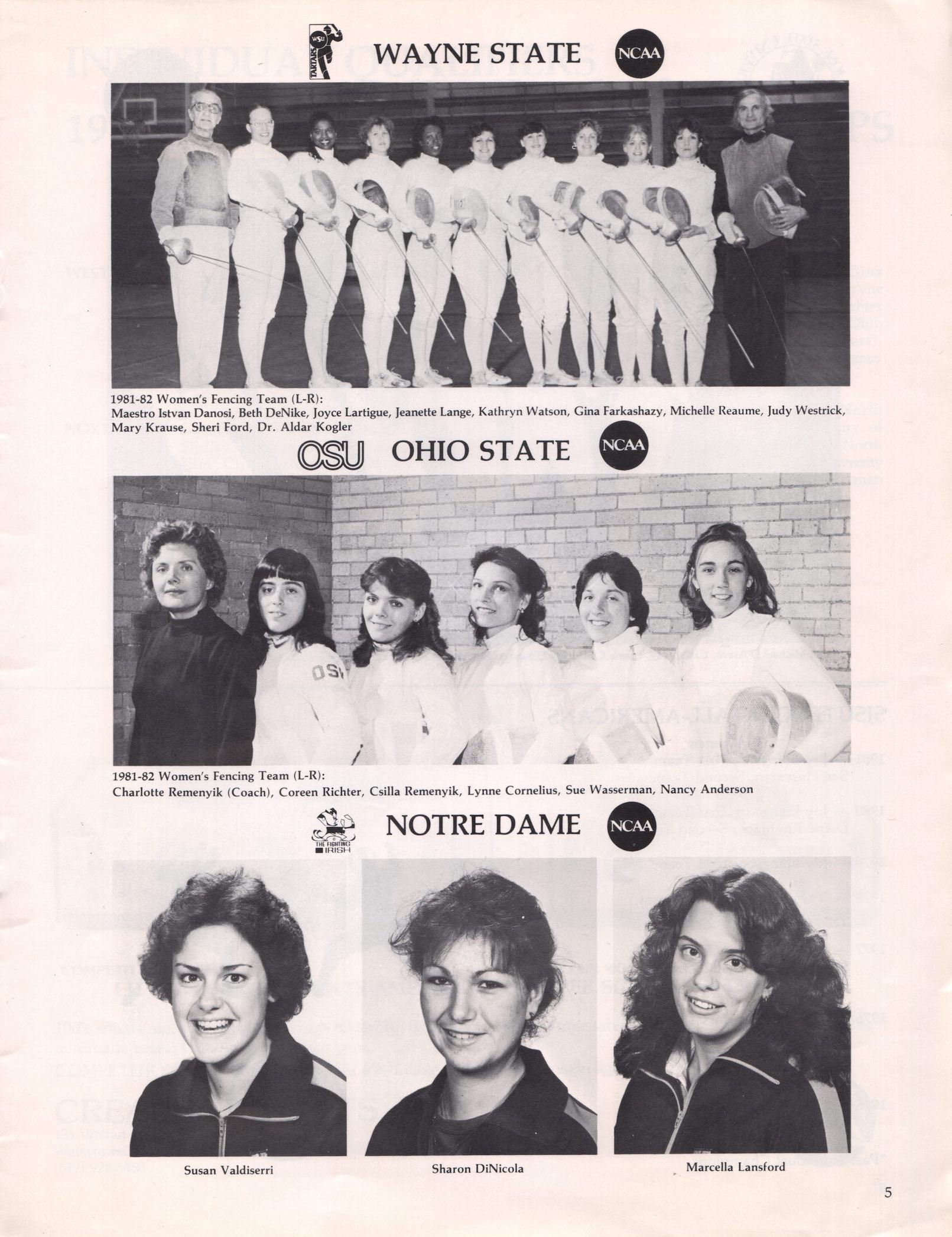

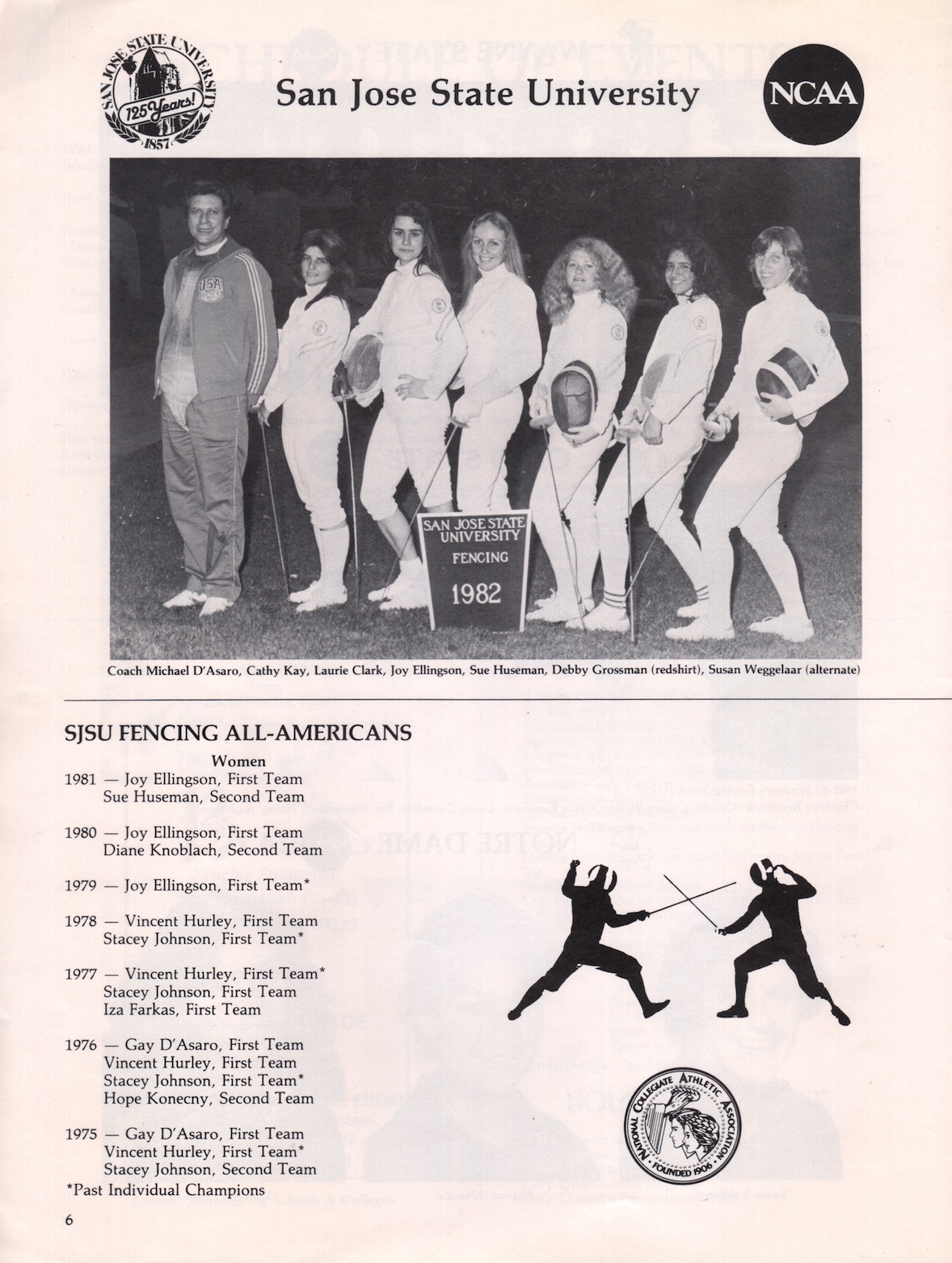

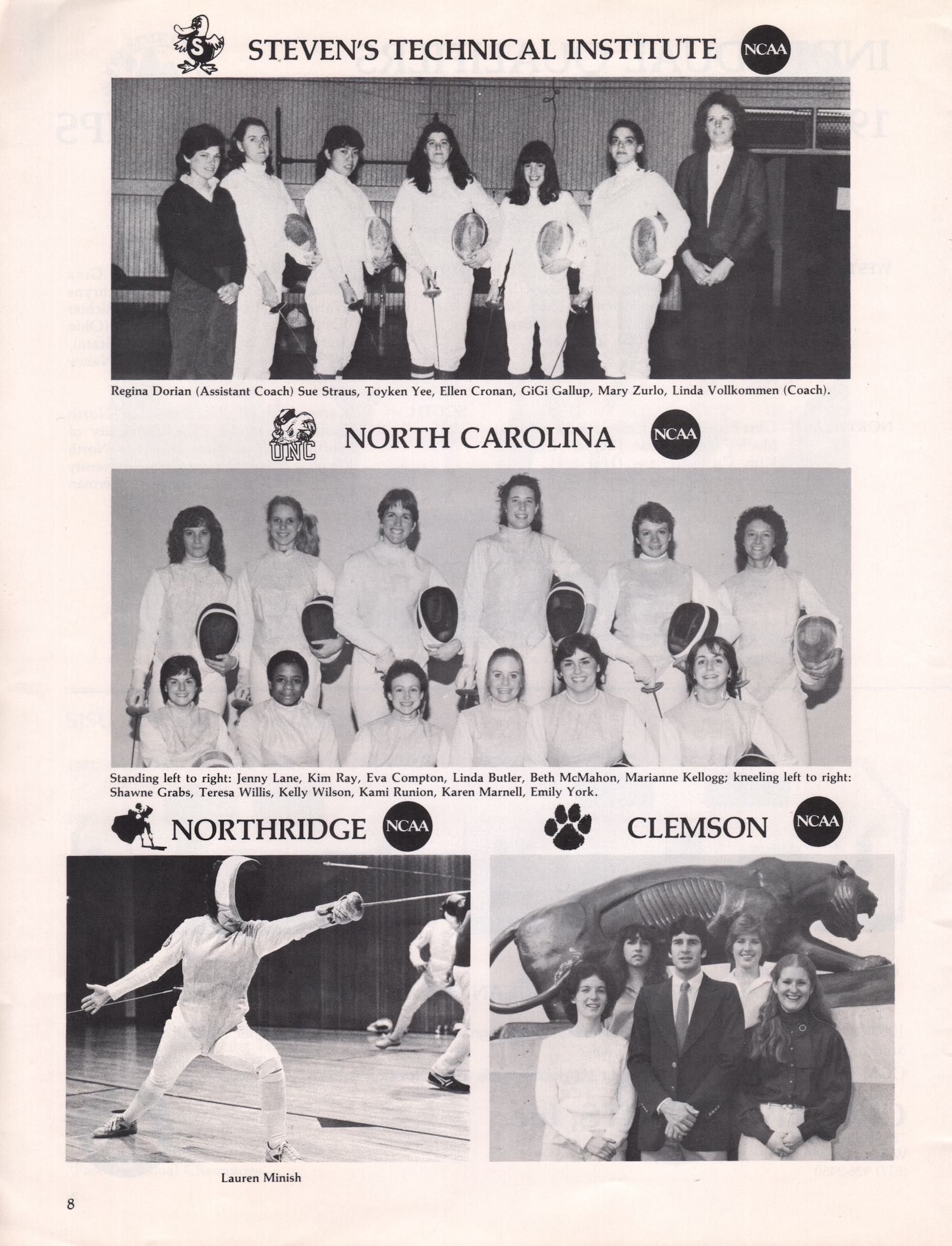

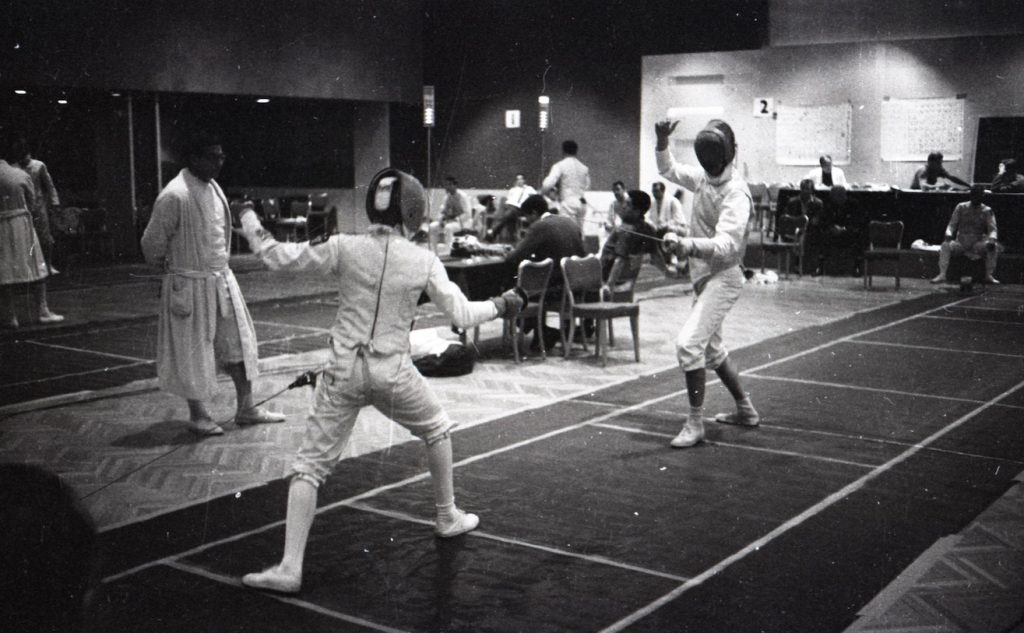

Eight universities took part in the first NCAA Women’s Fencing Championship. And when I say ‘Fencing’, I mean Foil Fencing. Epee and Sabre championship events for women didn’t materialize in the NCAAs until 1995 and 2000, respectively. (Olympics-wise, epee for women began in 1996 and sabre in 2004.) The participating schools were: Wayne State, Ohio State, Notre Dame, SJSU, Stevens Tech, North Carolina, Cal State Northridge and Clemson. Somehow or other, the program has traveled with me in an odd pile of ephemera from that day to this, so I’ve got all the details of teams and members.

The above three pages are from the official program. Why Northridge didn’t come up with a team photo is beyond my reckoning. Ruth Botengan was also on the Northridge team – and the only qualifier from that school for the individual event – and there must have been a 3rd member, but I don’t have a record of who that was.

Of those eight teams, the most memorable for me was the team from Wayne State as they came out a week prior to the event and trained with us in the San Jose salle. Gina Farkashazy had won the 1980 NIWFA, the whole team was well trained by Istvan Danosi and Aladar Kogler, and a tough matchup for the local Lady Spartans on our team. In my memory, everyone seemed to get along well. At San Jose, we weren’t unused to fencers from other programs coming in and spending time training with us, so having a group of foilists jump in for the week gave all of us new people to fence and that’s always fun. It was also a chance to get to know Aladar Kogler a bit and hear his stories of defecting to the West which he’d done not more than a year or two prior. I don’t know how long he was at Wayne State. I do know he started at Columbia in 1983, so probably not longer than a year or two at most. Kogler probably doesn’t remember me but I enjoyed listening to his stories and he was just so danged tan!

L-R: Istvan Danosi, Kathryn Watson, Jeanette Lange, Beth DeNike, Joyce Lartigue, Gina Farkashazy and Aladar Kogler

At that time and place, I was doing a great deal of officiating for foil tournaments so I got a chance to work this tournament as a member of the squad of ‘directors’, as we called ourselves back then. (We couldn’t be referees. No whistles.) I don’t have much in the way of memories of the individual matchups or other team events but I sure remember the gold medal team match between Wayne State and San Jose State. How I got picked to direct that whole match is anyone’s guess. I prided myself on fairness as an official and while I may have known my own San Jose teammates better, the Wayne State fencers (and coaches) must have decided that I wouldn’t cheat them out of touches. And I didn’t, but that was a tough match. Nobody gave an inch, it went back and forth, and I thought either Gina Farkashazy or my teammate Laurel Clark might actually attempt murder in their matchup. (Ok, not really – but that may have been the single toughest bout I ever officiated.) In the end, Wayne State came out on top. I didn’t record the final score and I wish I had. I’m sure it was close.

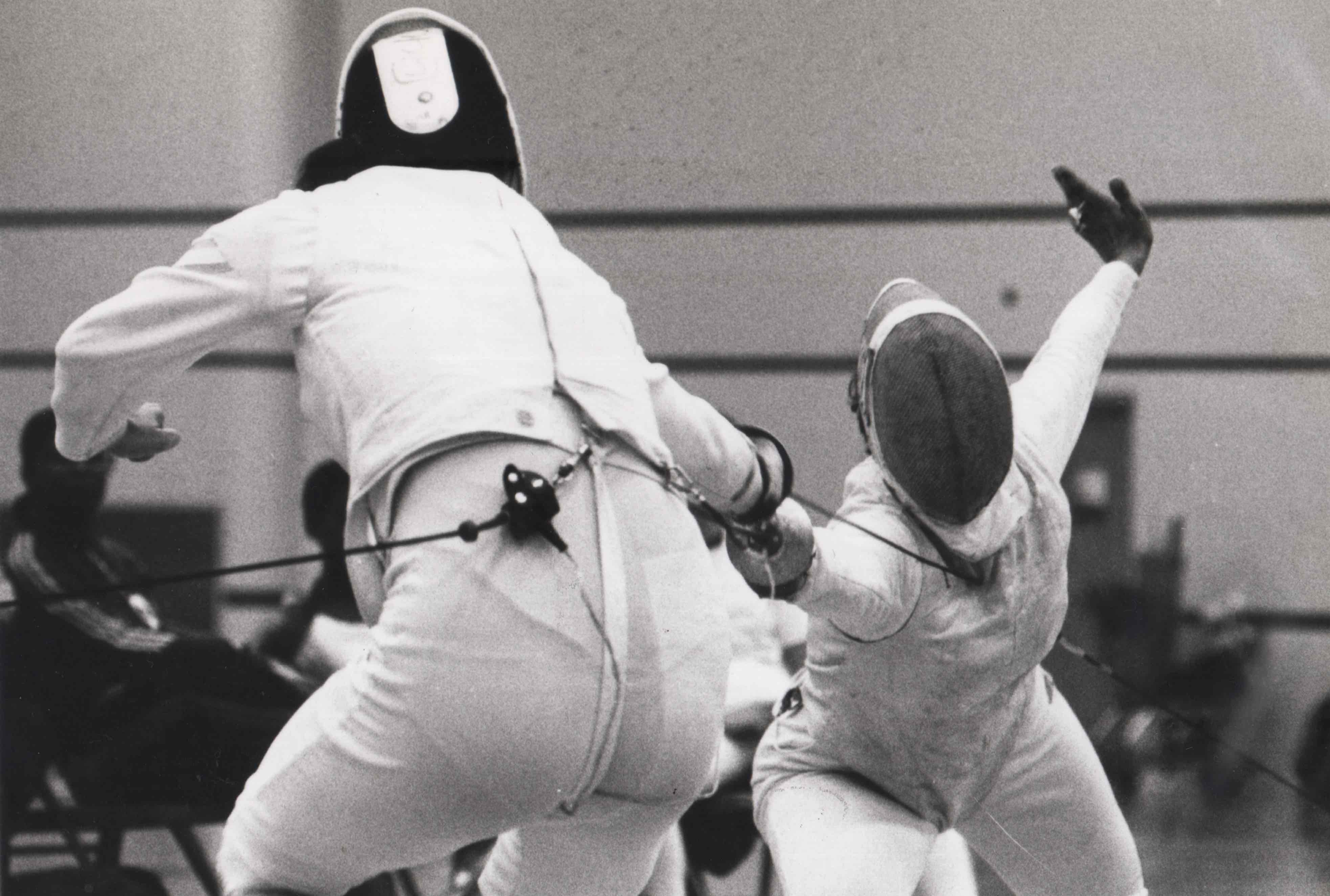

Laurel Clark (SJSU) vs Gina Farkashazy (Wayne State)

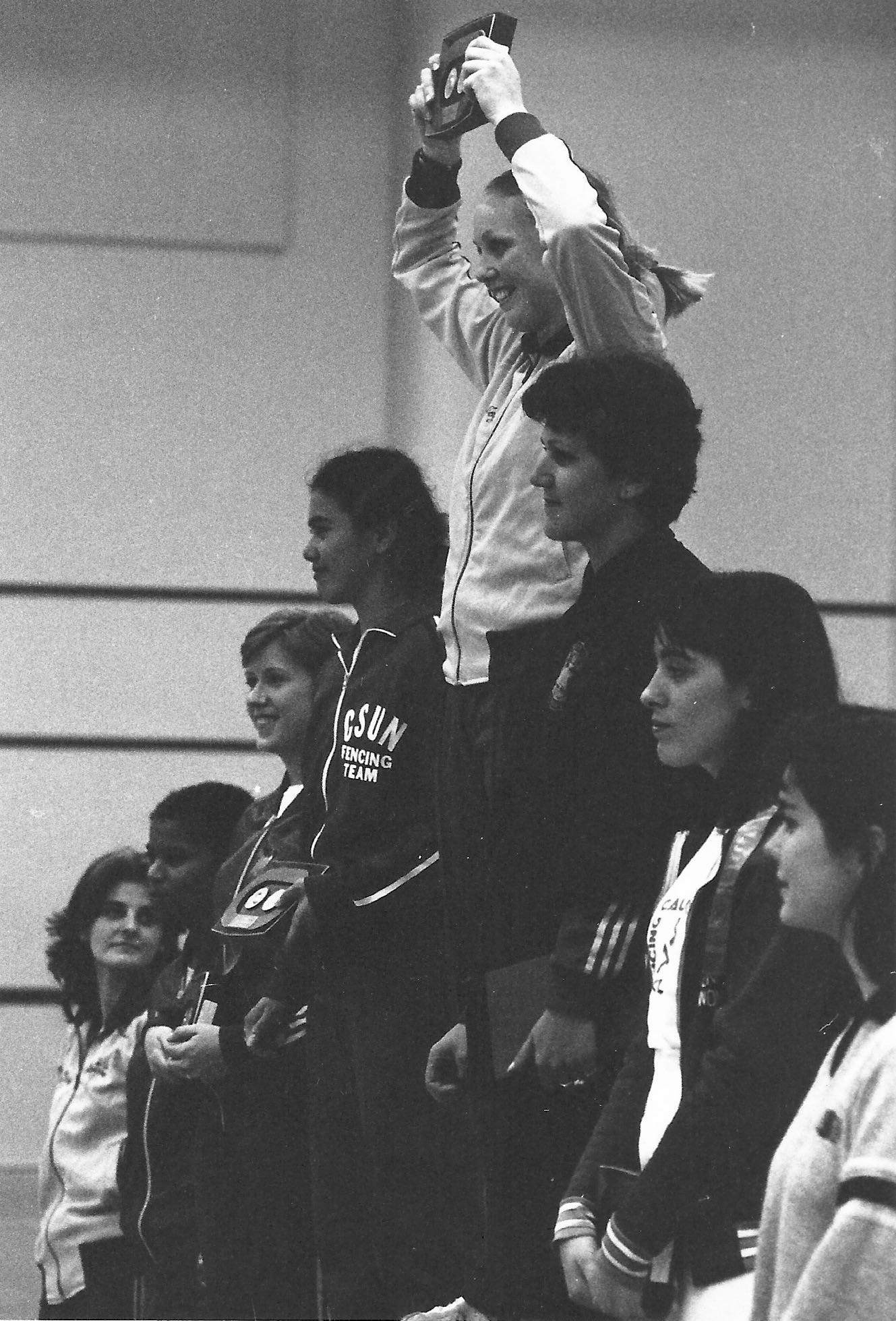

Joy Ellingson won the individual trophy, her second collegiate national championship since she had won the NIWFA title in 1979, the last of the 5-year unbroken streak by San Jose State. San Jose won the both the team and individual NIWFA championships from ‘75 to ‘79. Vinnie Bradford and Stacey Johnson traded individual titles from ‘75 to ‘78.

L-R: Cathy Kay (SJSU), Joyce Lartigue (Wayne State), Jeanette Lange (Wayne State), Ruth Botengan (Cal State Northridge), Joy Ellingson (SJSU), Gina Farkashazy (Wayne State), The One Person I Can’t Identify, Laurel Clark (SJSU)

This 1982 event marked the end of San Jose States’ prominence in the women’s championship ranks. After that year, they didn’t win another individual or team national championship. Within three years, Michael D’Asaro had retired and left the Bay Area after 18 years of coaching. Oh, and the university cancelled the fencing program. That was a fun day, let me tell you.

L-R: Cathy Kay, Joy Ellingson, Laurel Clark, Susan Weggelaar, Susan Huseman, Michael D’Asaro

Still, San Jose State hosted the first of what is now a much more prominent event with world-ranked women competing for the title of NCAA champion. Times have changed and US fortunes in the fencing world look a lot different now.

The Videotape Saga!

Back in August of 2017, I wrote a story about a donation to the Archive from Marc LeRoux. (Read it here.) Marc sent some terrific material about Dr. William O’Brien and the Letterman Fencing Club that hadn’t seen the light of day for many, many years.

Along with that material, he sent me a videotape. Not a standard, pop into a VHS deck kind of videotape. No, this was a 1” tape format which used to be standard for broadcast television but with the advent of digital video in the 1980s pretty much went the way of the dinosaur. Finding someone today that has a 1” video deck that’s working? I think dinosaurs are easier to find. Still, there are folks out there that keep a deck handy for just such a client as myself and I found a transfer house out in Massachusetts that said they could handle it.

About the tape. The only labeling on the tape reel is the cryptic notation “71C” on a piece of masking tape. The outside of the box has a half-torn piece of masking tape with the notes “7/29” and “Sabre Comp DRIMBA” and nothing else. No other labeling of any kind. Ion Drimba, the Olympic Gold Medalist in foil at the 1968 Mexico City games, has been brought up here before. Peter Burchard speaks about his Drimba experiences here. Drimba competed internationally in both foil and sabre for a decade before defecting from his communist home country of Romanian to West Germany during the 1970 Challenge Martini in Paris. After time in Germany and Tuscon, Arizona, he landed in San Francisco and became the coach at the Pannonia Athletic Club.

Now, at no time of which I am aware was the 1” video format available in anything like a portable video rig, excluding high end sports productions that brought all the equipment they’d need in huge 18-wheel trucks. 1” decks were bulky, heavy and easily knocked silly. You didn’t want to haul them around willy-nilly and expect them to continue working.

Thus, my thoughts about the tape were that it must have been shot by some highly professional production company with access to broadcast quality equipment. And so, it must be from a major competition. What else could it be?

With high hopes and all good intentions, I packaged up the tape and sent it off. It was a nice summer day in June. Of 2017. I got the tape and transfer back. Yesterday. February 21, 2019.

Over a year and a half. Thank god nobody was waiting for it with money on the line.

When I first sent it out, I was in touch with the transfer place. About a week or so after they got it, they were able to put it up on a machine to take a look. It played! That was the good news. The more cryptic news was that the tape contained mostly some kind of modern dance and “some fencing at the end”. I asked them to go ahead and transfer everything, not knowing whether the dancers were fencers or what the heck it might be.

And then, nothing.

I called. I left messages. Sent emails. Called again. Emailed again. After about six months, I’d pretty much given up hope. Calls not returned, nothing by email. Just… nothing. About every couple of months, I’d send out another email, but really, I didn’t expect I’d ever hear anything. In January of 2019 – hey, it’s the New Year! A time of renewal! I sent another email. Not angry, just, you know, hoping I could someday get the tape back.

Lo! Not two weeks ago, my phone rings at around 7am (CA). I ignored it. When I finally listened to the message, it was the guy! The guy with my tape! It seems he’d been in and out of the hospital for most of the last year plus and apologized profusely, said he had a friend helping him with his backlog and he’d move my tape to the top of the list. Sure enough, yesterday the tape arrived back in my hands, safe & sound, along with a digital video copy and a DVD. You can bet I didn’t waste any time getting that DVD into my player.

What I found was… interesting. First, it’s in black & white. Now 1” decks were entirely capable of color. Why black & white? The only thing I can figure, based on what was shot and how it looks, is that the footage was all originally shot on the pre-VHS ½” reel-to-reel videotape systems that were prevalent in the mid-1970s – and were reasonably portable – then transferred to the 1” format tape. God knows why. But, not complaining. It survived to the Now.

The modern dance, almost 40 minutes of it, looks like a recital for a dance class after a semesters worth of practice. A fair number of performers. Not on a stage, but in a room. No applause or restless crowd noise, so no audience. All the dancers have Seventies hair and dance tights. The guys have Seventies mustaches. Trust me, that’s as much as you need to know.

And so, La! To the fencing!

It’s about six minutes long and filmed in the Letterman Gymnasium. I recognize quite a few fencers and spectators. The only fencers I recognize are Ion Drimba and Joe Shamash. And yes, it’s a sabre tournament. I very much wish it had been foil, as that was Drimba’s (and Joe’s) strongest weapon. There are a couple of other fencers, but I don’t know who they are. A couple of Santa Cruz-based side judges can be seen. Pretty sure we’ve got Bob Tripp and Rick Simpson in there. And among the spectators, Dr. William O’Brien of course. It was at Letterman, after all. I also spotted Joe Manzano and Eleanor Turney. There are probably half a dozen other folks who can be seen pretty clearly, but I don’t recognize anyone else.

Date? Early 70s? Mid-70s? Joe S. or Joe M. may recognize some folks and be able to put names to them, but anyone can play! If you see someone you know, raise your virtual hand!

To save your immortal soul I have removed the dance segment. Here is the fencing part:

https://youtube.com/KZciAcBwzOg

An Abundance of Riches

Although I haven’t posted a story in a couple of weeks, it’s not due to lack of material to write about. There are a ton of stories I need to complete, not least is one about a recent visit I had with the family of a long-time LAAC fencer – and Olympian – who shared some amazing material and family stories with me. That’s the big-ticket item in the hopper currently, but in the process of transferring scans from my portable hard drive to my 5 terabyte storage drive, I came across a series of photos I’d nearly forgotten about.

These snapshots were taken at the 1963 US National Championships held at the Statler-Hilton Hotel in Los Angeles. The event ran flawlessly, “…a fact that we have come to expect from Southern California and its Chairman, Fred Linkmeyer.”, as Harold Goldsmith wrote in American Fencing magazine. In attendance at these Nationals was first-time National competitor, Julie Moore, later Julie Selberg, along with her teammates Jan Meyerson and Diane Amidon. They comprised the North Dakota women’s foil team that was defeated in the preliminary round by Santelli, Pannonia and Salle du Nord. Charlie Selberg’s Selberg Fencing Academy from Fargo, ND, sent a large contingent out to LA for Nationals that year. At least seven fencers went, maybe eight. Almost all were eliminated in the first round, with a couple of exceptions. Julie made it out of the first round in the Women’s Foil individual. Steve Werre, the youngest competitor in the field at around 14 years of age, made the 2nd round in the Men’s Foil individual, and Selberg’s Men’s Sabre team squeaked out of the prelims after the Cavaliers team fielded only two of the three fencers they needed.

Regardless of how they finished, their greatest gift to the future was putting eye to viewfinder and preserving a great bunch of photographs that I recently unearthed from a large cache of previously unsorted photo sleeves. It’s funny, every time I think I’ve dug through all the boxes and sorted through all the chaff to find the nuggets of historical gold from the Selberg Collection, I’ll happen across something by accident that had previously escaped my attention. Well, these caught my eye and I share the best of them with you now.

That’s youngster Steve Werre from Fargo, North Dakota on the left, facing down an opponent who’s likely much older than he.

The unmistakable smile of Ed Richards, who took the first place medal in Individual Foil at this Nationals.

The Letterman Fencers team. From left, Severo Pasol, Peter Schwarz (I surmise, based on the seating arrangements) and Colonel Brownlee. The woman on the far right is unknown to me.

Not sure who Dr. William O’Brien, longtime coach at San Francisco’s Presidio based Letterman Fencers Gym, is chatting with here. That’s Bill on the right.

On the left, David Micahnik, 1960 National Epee champion. On the right, Uriah Jones, perpetual threat to win who eventually captured the National Foil title in 1971.

I’m not certain who the fencer on the left is, but in the three chairs on the right we have, first, Ferenc Marki, then coach at the Pannonia Athletic Club in San Francisco, Jan Meyerson from Fargo, ND who eventually moved to San Francisco and worked at American Fencers Supply, and on the right, a smiling (and why not?) Csaba Elthes.

A nice moody portrait of Szeged-born Ferenc Marki, student of Laszlo Borsody, and Maestro to Olympic Gold medalist Daniel Magay, World Champion Joszef Gyuricza and Junior World Champion Tom Orley.

Marki with Pannonia fencer Jim Green.

At the scorer’s table, Jim Green with Severo Pasol standing over his shoulder. On the right I believe is a young Diane Amidon, another of Selberg’s Fargo crewe, who would win the first “Under 19” US National women’s title in 1966.

The lighting isn’t good, and he isn’t smiling here – ok, neither of them are – but that’s Csaba Elthes with Ferenc Marki.

One of the de Capriles brothers checking his watch. I think that’s Joe. Could be Mike. Tough to tell at this angle for me. But behind (above the wristwatch) is definitely Stan Sieja, head fencing coach of the Princeton Tigers for almost 40 years.

And finally, Gerard (Jerry) Biagini gets an assist from Pannonia teammate Jim Green in preparation for a bout in the team foil competition. Pannonia ran fourth, losing the bronze medal match to Csiszar.

So many more stories in the hopper. I’m working on them, believe me. Much to share! Soon!

The Glamorous Photos of Erich Funke d’Egnuff, Part 1

I’ve been reviewing various possibilities for scanning the wonderful scrapbook of Erich Funke d’Egnuff that was gifted to The Archive by longtime Letterman fencer Marc LeRoux. (See: here) It’s proving to be a rather tricky proposition. The date range of the scrapbook is from April of 1937 to April of 1945 and there is an absolute trove of news clippings containing information about the various events, competitions, coming out parties and all manner of fencing related events that people today don’t even think of as possibilities. It’s a challenge to scan because the pages of the book are bound into a hard spine. Unlike every other scrapbook of the era and beyond that is in The Archive collection, it isn’t tied together with string or held together with pegs or any other reasonable (to me) method. Hardbound. Firm spine. What this means is I can’t put it on my flatbed scanner to get high resolution, flattened scans. I mean, I could, but by doing so I’d be endangering the integrity of the spine and possibly the pages themselves. So that option is out.

I have some other methods to attempt for a satisfactory solution, and I may have to wrap in my professional photographer brother Garrett to set up a means by which we can get an uncompressed photo file with a camera while utilizing some sort of non-damaging glass page flattener. It’ll be a tricky rig; some of the newspaper articles are folded into the page and, when unfolded, are much larger than the album page, so we’ll need something that’s adjustable for multiple sizes. With help from my brother, I’m sure we can figure it out. He’s clever about such things.

In the meantime, I did a very quick, non-invasive pass through the whole scrapbook with my little Canon Powershot, which is easy to use and has a reasonable image resolution but can’t shoot anything but .jpeg images which aren’t fully satisfactory for archival preservation. But they at least give me something to look at without opening the scrapbook every time I want to find out who won the local Sabre Open in August of 1938. That was Ferard Leicester, for those of you playing Archive Bingo.

While taking a pass through the photos of all the pages recently, something jumped out at me that I hadn’t really contemplated before. Throughout the scrapbook, old press photos, pictures taken by staff photographers from the various local newspapers in San Francisco, were way, way cooler than the pictures we see of fencers in the papers today. What happened? I mean, some of the compositions are wacky, some took a lot of imagination and planning to create, and some are just excellent portraits. Was it because a photographer back then was taking a black & white photo? Is there something about the way news photographers were trained, or some special consideration related to printing? I could speculate all day, but it just seems that somewhere between the photographers, the subjects and whoever else was advising – and I think I must give credit here to Erich Funke d’Egnuff, as he seemed to be intimately involved in all this – they came up with some really interesting photos.

I’ve cut out captions that intruded into the photos. Some of the cuts and crops they used to get around type is a study in and of itself on newspaper layout shape shifting. And, since the photos of these images were taken without the ability to flatten all the pages I had to download Photoshop (finally) and learn how to use the Perspective Warp tool. So that’s a plus.

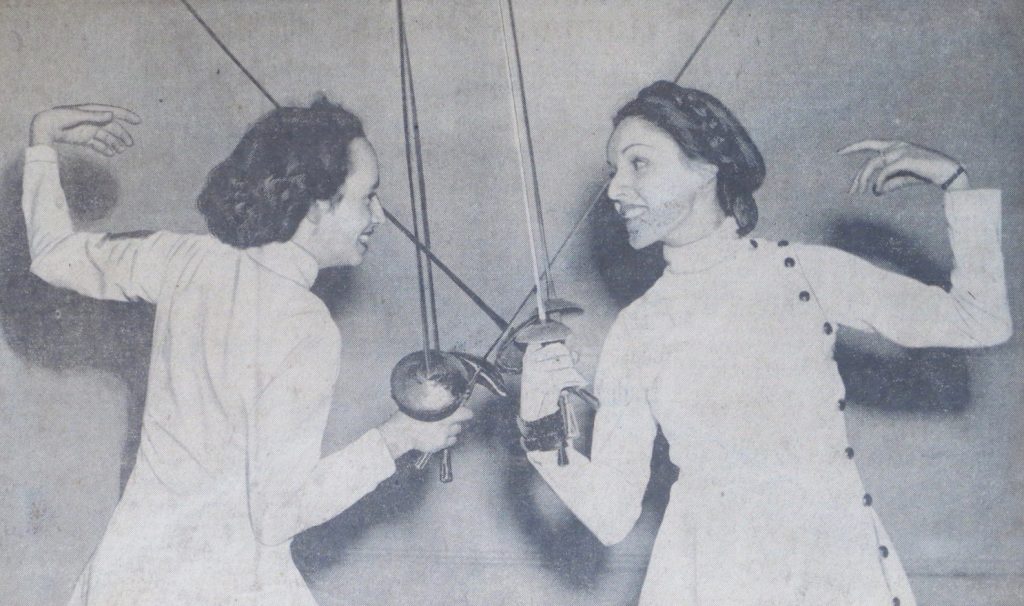

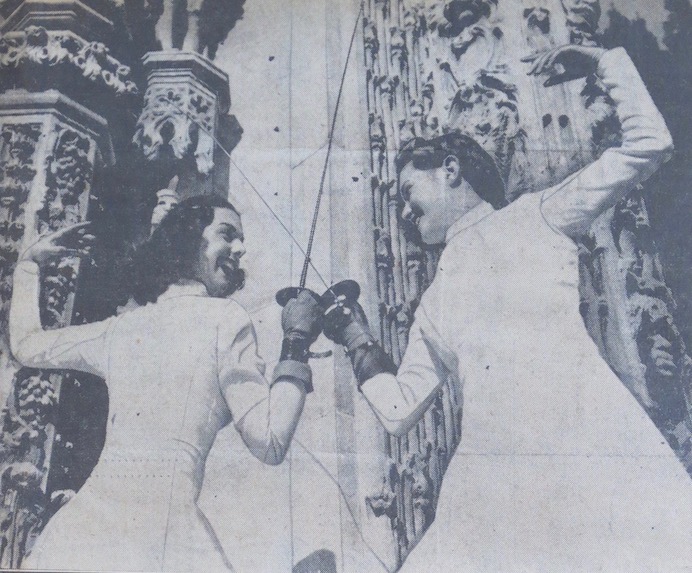

“It was Ladies’ Day yesterday at the Emporium Auditorium.” That’s Mrs. Erich A. Funke up top and Miss Helen Sander in this photo from the San Francisco Chronicle, June of 1937. Where was the photographer? In the rafters? The angle is from directly above the fencers. You wouldn’t get this from a ladder. Impressive.

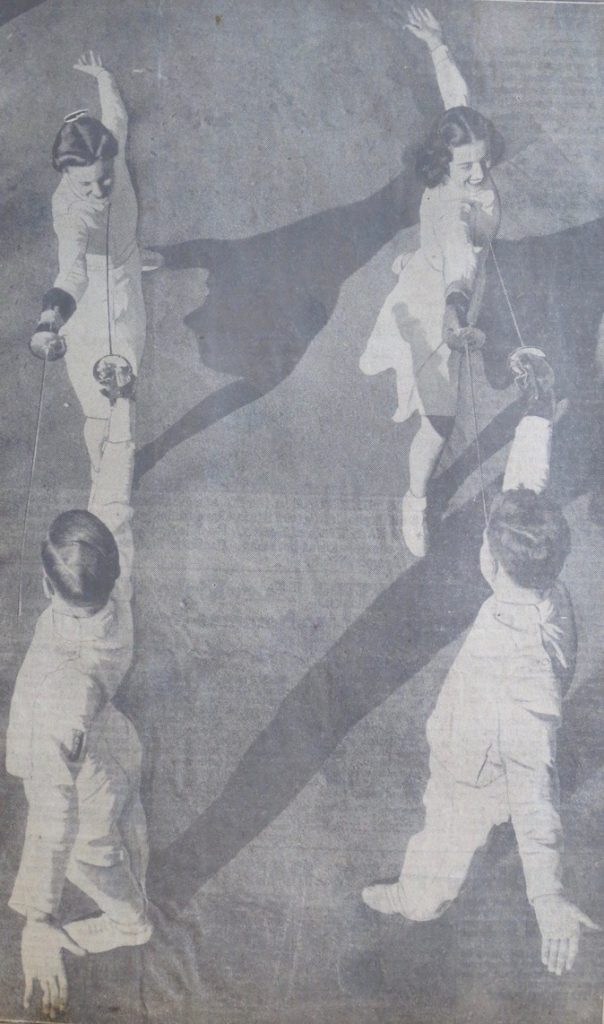

That’s Miss Marcelle Woollen and Miss Jovita Bonniwell in this photo out of the San Francisco Examiner from July of 1937, advertising a tournament sponsored by the Examiner. An interesting effect – each one of the young ladies is holding not one, not two, but three foils. Maybe they had hoped to get some low-end impression of a stroboscopic effect? Anyway, I don’t think this is what was meant by a ‘three weapon tournament’, even though such events were very popular back in the day.

Caberia Teresi in a photo from July 2, 1938’s SF Chronicle advertising a July 4th program at Kezar Stadium, former home of the San Francisco Fourty Niners. I assume the fencing exhibition/competition took place outdoors, as it was held in conjunction with a drill competition. “…part of the city’s Independence day celebration.”