Random Stuff

Trying out still more page formatsJust A Standard Page

Nunc et vestibulum velit. Suspendisse euismod eros vel urna bibendum gravida. Phasellus et metus nec dui ornare molestie. In consequat urna sed tincidunt euismod. Praesent non pharetra arcu, at tincidunt sapien. Nullam lobortis ultricies bibendum. Duis elit leo, porta vel nisl in, ullamcorper scelerisque velit. Fusce volutpat purus dolor, vel pulvinar dui porttitor sed. Phasellus ac odio eu quam varius elementum sit amet euismod justo. Sed sit amet blandit ipsum, et consectetur libero. Integer convallis at metus quis molestie. Morbi vitae odio ut ante molestie scelerisque. Aliquam erat volutpat. Vivamus dignissim fringilla semper. Aliquam imperdiet dui a purus pellentesque, non ornare ipsum blandit. Sed imperdiet elit in quam egestas lacinia nec sit amet dui. Cras malesuada tincidunt ante, in luctus tellus hendrerit at. Duis massa mauris, bibendum a mollis a, laoreet quis elit. Nulla pulvinar vestibulum est, in viverra nisi malesuada vel. Nam ut ipsum quis est faucibus mattis eu ut turpis. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Maecenas nunc felis, venenatis in fringilla vel, tempus in turpis. Mauris aliquam dictum dolor at varius. Fusce sed vestibulum metus. Vestibulum dictum ultrices nulla sit amet fermentum.

LA’s Greatest Hits, 1936

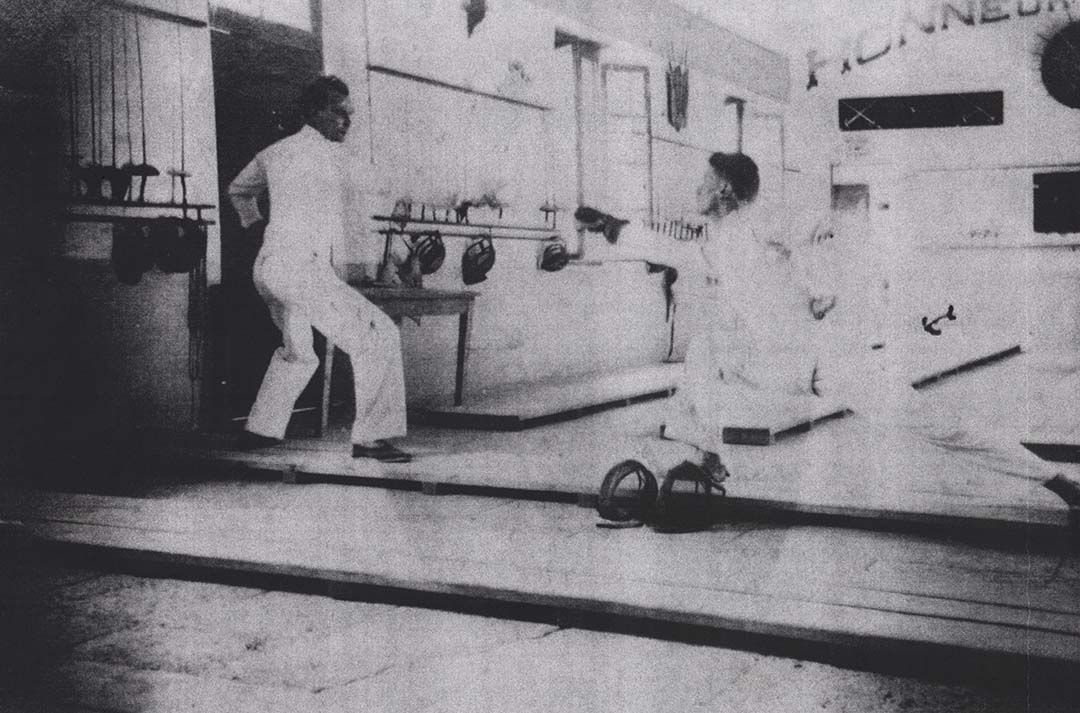

When I have the opportunity to visit someone who has fencing memorabilia that I can scan for my collection, I often don’t get a chance to thoroughly take in the significance of everything I’m working with. I work fast, replacing one item from the flatbed scanner as soon as the scan is done, dropping another item down to replace it and setting up the next scan. So when I get a chance to go back and look, I’ll have that moment of revelation, thinking, “Boy, am I glad I scanned that piece!” That’s definitely how I came across today’s topic. The small section at the top of the page is only a tease for the astonishing evening performance that the Los Angeles Athletic Club held on January 3rd, 1936.

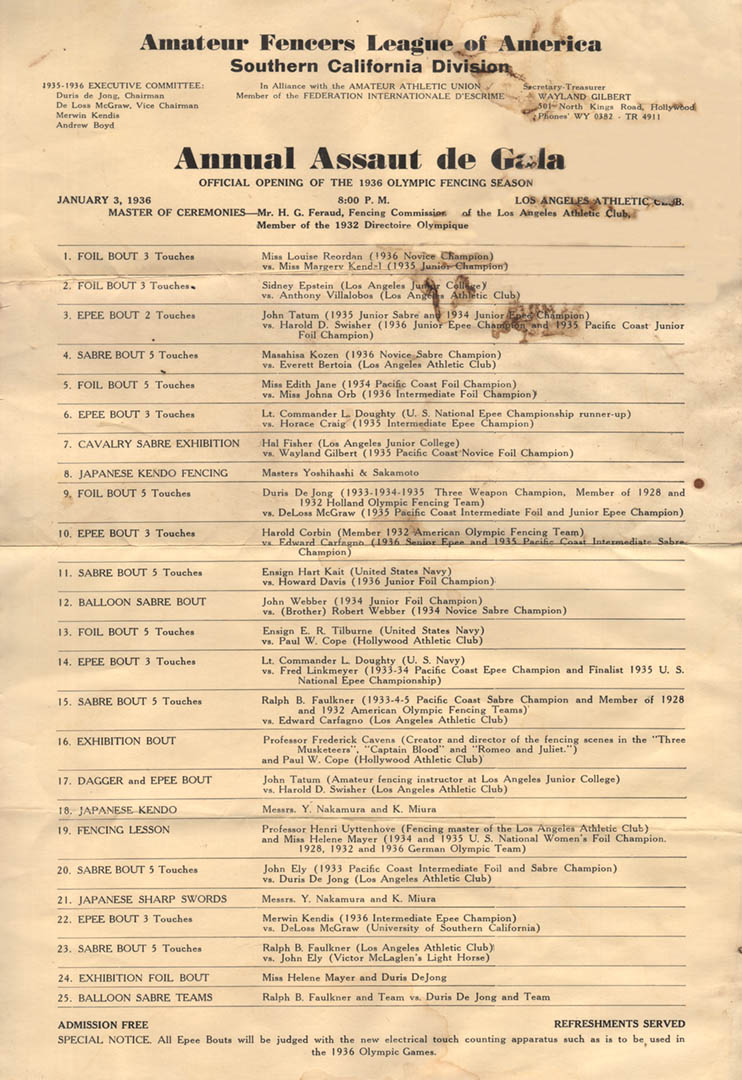

The evening’s program for what was apparently an annual event at the LAAC. Billed as “the opening of the 1936 Olympic fencing season”, this Friday evening certainly provided the goods. Among the 25 events for the evening, four past Olympians participated in seven of the events, including 1928 Olympic Gold Medalist Helene Mayer.

This handbill is from the fantastic collection of memorabilia that I was able to scan thanks to the generosity of the family of 1936 and 1948 Olympian Andrew Boyd. (See more about Boyd and my visit to the Owens Valley here.) As per usual, I ran across this piece while looking for something else. I’m in the process of trying to track down information about a fencing book written by Boyd’s coach, Henri Uyttenhove. While reviewing my Uyttenhove material, I took a look at this program and became enthralled with the wide variety of fencers involved in this evening of entertainment. As I ran down the list of participants, I thought it would be fun to give a bit of a play-by-play of the folks I can identify. So I’ll work from the top down and talk story about the players.

The first four events, clearly the preliminary rounds, are handled by folks who’s names are entirely unfamiliar. I haven’t tried to go through what little documentation exists from this era. The tournaments these fencers can lay their claims of victory for wouldn’t be likely to show up. There isn’t much info to go through. So just some names of once-upon-a-time fencers who didn’t have a great impact upon the sport. When we get to #5, we have a ‘known’ name.

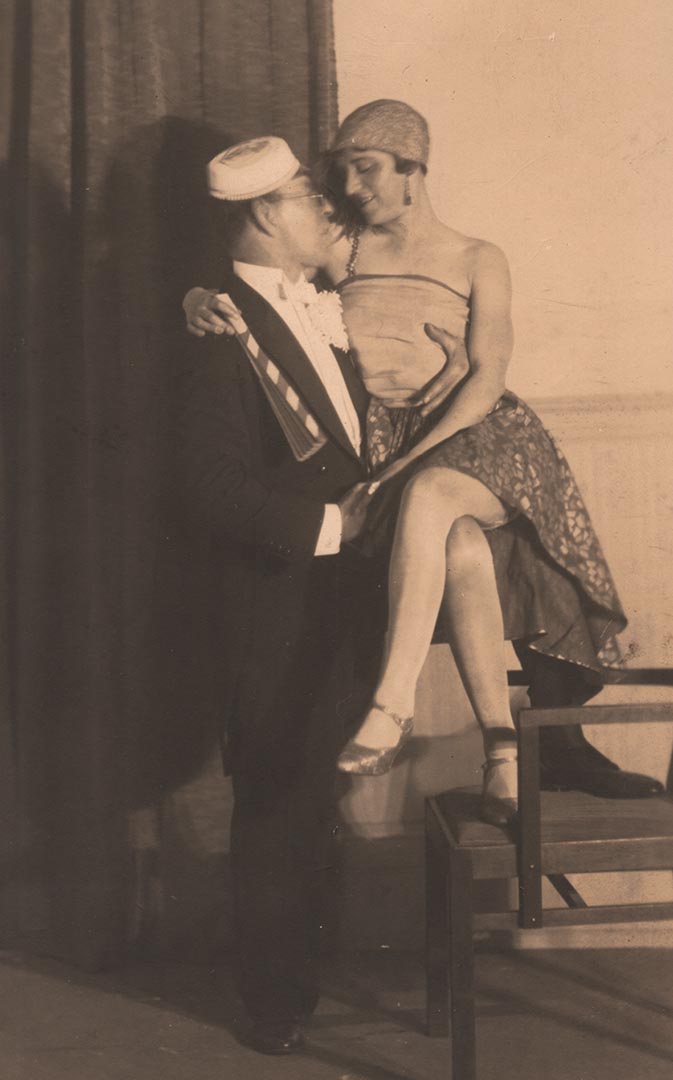

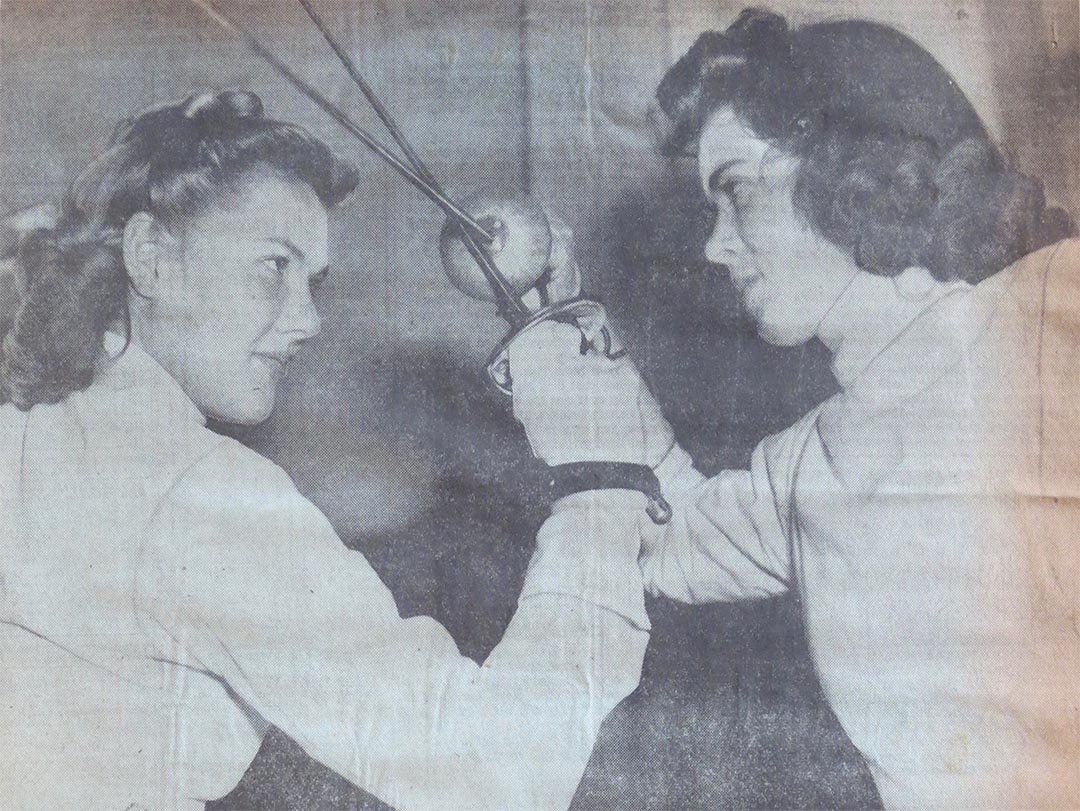

This photo, courtesy of Andy Shaw at the Museum of American Fencing, shows Edith Jane, later Edith Jane Faulkner, on the left performing at a some Hollywood event or other. Capable of winning the Pacific Coast Women’s Foil title when Helene Mayer was otherwise occupied, Edith Jane was better known as the dance instructor at the Falcon Studios space she shared with fencing instructor/Olympic fencer/actor/fight choreographer/future husband Ralph Faulkner. I haven’t been able to ID the other woman in the photo. And what swashbuckler movie premier were they helping promote? No idea. This was taken in the courtyard of Sid Grauman’s Chinese Theater. Edith’s front foot is planted squarely on Eddie Cantor.

After an epee bout, we get to a couple of the more curious inclusions in the program. First is an exhibition of cavalry sabres, followed by a demonstration of kendo. In 1936, Torao Mori had not yet arrived in Los Angeles to teach kendo and learn Western fencing from Henri Uyttenhove at the LAAC, but LA already had a well-established tradition of kendo in the local Japanese community. After the kendo, the first of the Olympians takes the stage.

Duris de Jong was a two-time Olympic team member for the Netherlands, competing in 1928 and 1932. Interestingly, the Netherlands didn’t send anything like a complete team to Los Angeles in 1932. However, de Jong was already living in LA. Since he’d competed in 1928, he applied to the Netherlands Olympic Committee to be allowed to hop on the Red Car heading down to Exposition Park and step onto the team. Since there was no cost to consider and he was a past Olympian, it was an easy decision to give him the green light. He went out in the Semi-Finals of the Men’s Foil individual, dropping all his bouts in a pool of nine. Of interest to me, in 1928 in the Men’s Foil Team event, he won a 5-3 decision in a bout against György Piller of Hungary. Piller fenced in both Team Foil and Team Epee in 1928, which was the year before he began his domination in sabre. Piller’s record in his two 1928 events was 4 wins, 15 losses. Compare that to his dominance in sabre at the 1932 Games, where he finished 30-2.

Duris de Jong’s first foil bout is against DeLoss McGraw. McGraw is a name I’ve run across before, and I imagine he gave a good account of himself against the two-time Olympian. The next match, #10, is a very intriguing matchup, pitting 1932 Olympian Harold “Hal” Corbin against up and coming fencer and Hollywood professional Edward Carfagno. There is a great interview with Corbin you can check out here where he talks about his 1932 Olympic experience – and suggests that if they were still using point d’arret in the LA Olympics of 1984 he’d still have been good for a few touches against the youngsters.

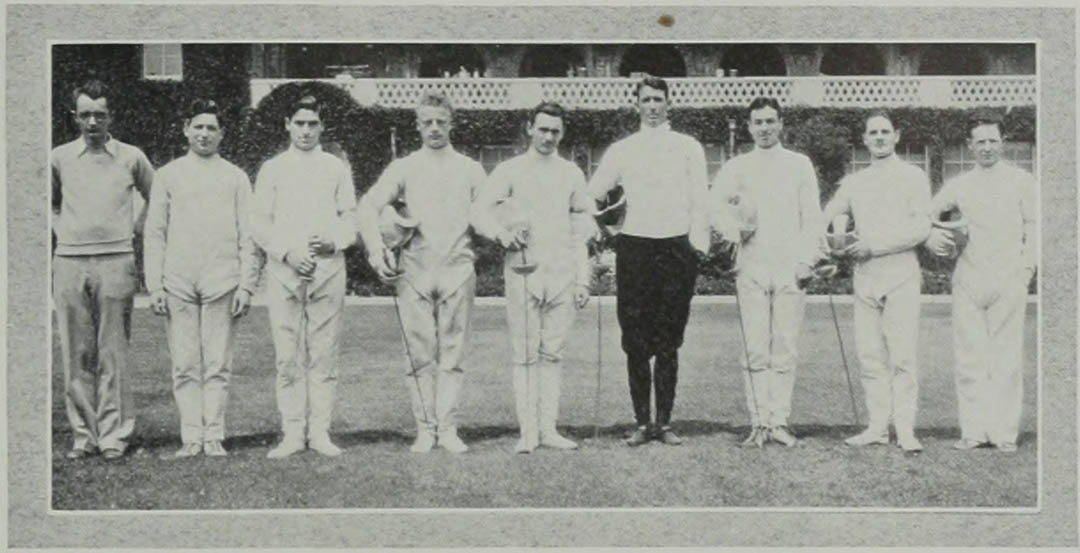

Hal Corbin in the center, just to the left of UCLA coach John Duff, who is a whole story on his own. There aren’t many photos of Corbin that I’ve run across so far. He had a long fencing life in Southern Cal and won a lot of tournaments.

Corbin’s opponent in his epee bout is Edward Carfagno, a two-weapon threat in foil and epee who finished 2nd in foil at the 1939 US National Championships that were held on Treasure Island in San Francisco. Carfagno was named to the 1940 Olympic foil team, but of course that Olympics never took place due to the turbulence of war throughout Europe and Asia. Fencing was not what Carfagno was best known for, however. He was a three-time Academy Award winning Art Director, probably best known for his work on Ben Hur (1959), but he also worked on the original Twilight Zone TV series.

After some foil, sabre and Balloon Sabre bouts (don’t know, can’t explain) we arrive at match numbers 14 & 15. The first features Fred Linkmeyer in an epee match against Navy pilot Doughty. I don’t know a lot about Doughty, but I’ve seen notices where his presence at tournaments in both Southern Cal and Northern Cal were dependent upon the weather and his schedule. An active duty Navy pilot, he was known to fly up to Nor Cal for tournaments when he had a chance. Linkmeyer was a perennial finalist in the Pacific Coast Championships, multi-time National finalist in epee and a dedicated administrator for the sport.

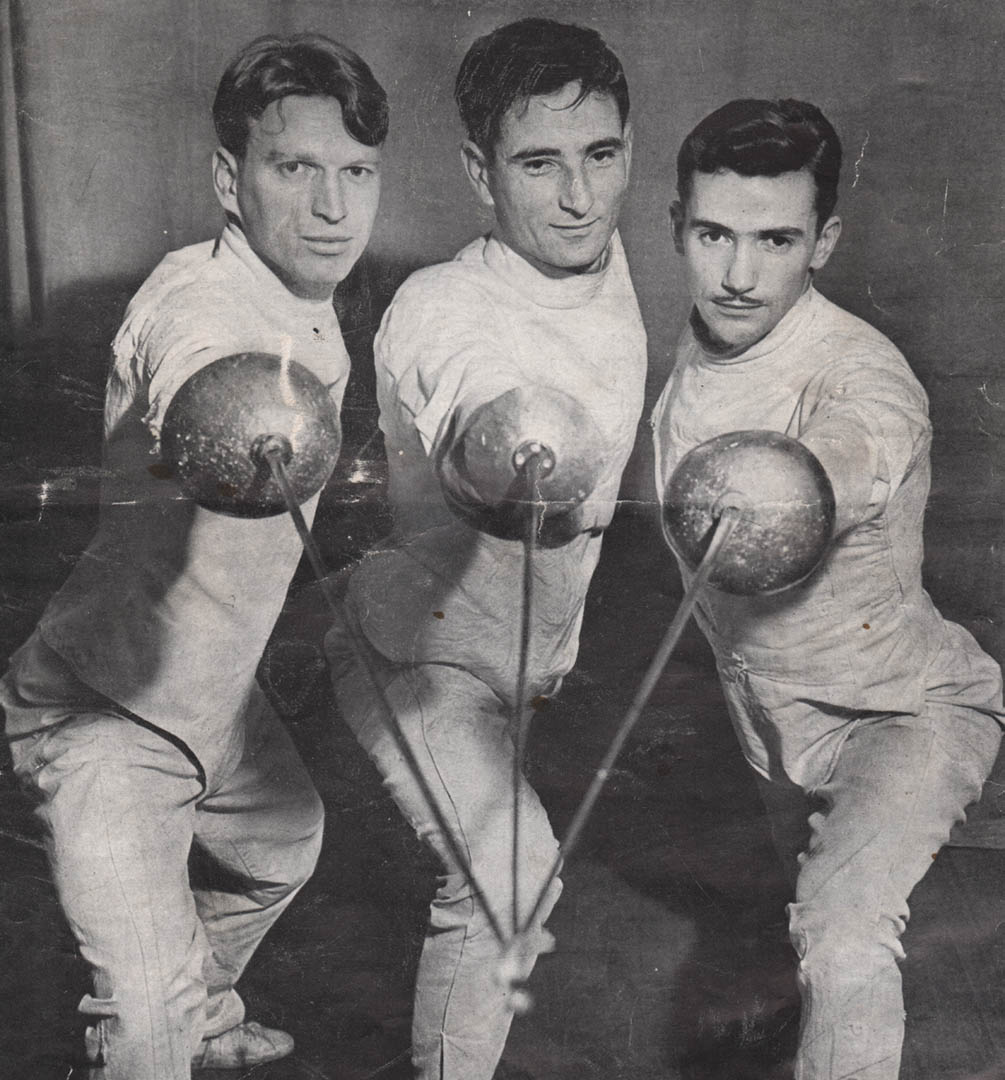

A cover photo from the in-house magazine from the LAAC. Left to right, Fred Linkmeyer, Edward Carfagno and Andrew Boyd.

Linkmeyer and Doughty are followed by Faulkner and Carfagno in a sabre match. Faulkner, like de Jong, was on the 1928 and 1932 Olympic teams. In 1928 Faulkner never got on the strip, the East Coast hegemony in charge determining that he didn’t have the quality to match up on the international scene. Maybe they were right, but in 1932, in his only Olympic bouts, up against the soon-to-be-gold-medal-winning Hungarian team, Faulkner went 2-2 with the rest of the US squad winning only one other bout against Piller & Co. So there that is.

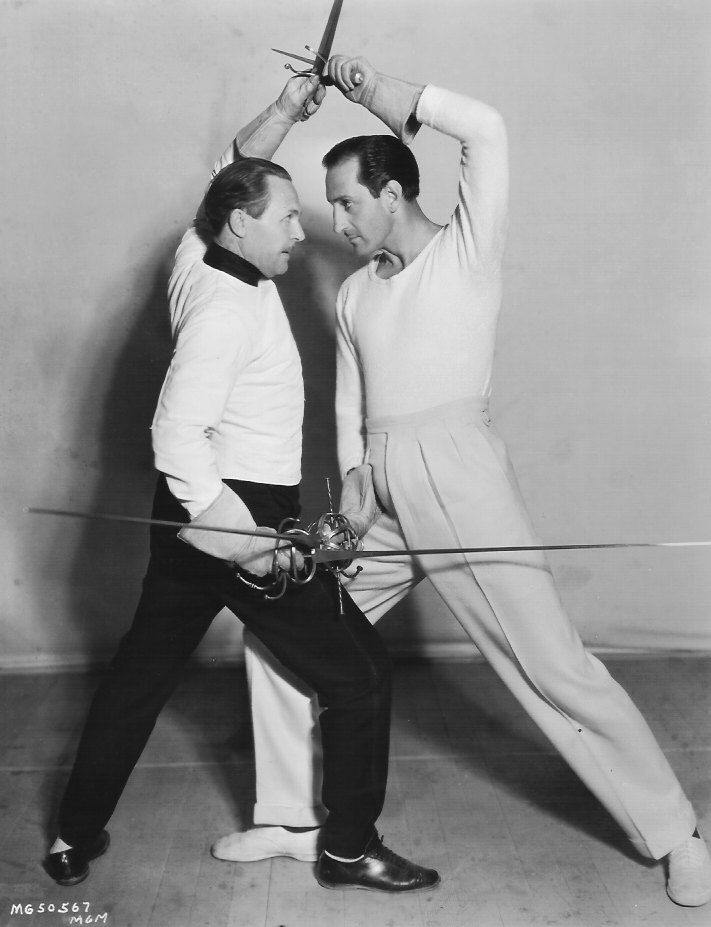

The next match is particularly curious. Fight choreographer and fencing master Fred Cavens puts on a “Exhibition Bout” with a member of the Hollywood Athletic Club. Was it a choreographed show-piece? Did they fence a serious match?

Fred Cavens at work. In this publicity pose, Cavens goes toe-to-toe with Captain Blood’s arch foe, Levasseur, also known as Basil Rathbone. Cavens did a ton of work in Hollywood. He was the frequent target of Aldo Nadi, once he arrived on the Hollywood scene, who considered Cavens the archetype of fencing master Hollywood used in lieu of those who knew fencing better. Such as Aldo Nadi. It’s entirely possible that Cavens was easier to get along with on set.

Cavens did not often venture beyond his Hollywood bubble, so it’s difficult to assess his skill as a fencing master. He did not, to the best of my knowledge, produce competitors. I’m not sure he even attempted to. With scads of film credits to his name ranging from 1920 to 1962, it’s quite possible he didn’t have time to bother with competitive fencing. He trained in Belgium, graduating with a degree from the Military Institute of Physical Education and Fencing, so it would seem that, competitive experience or not, he had a decent idea of what he was doing. In looking at his list of credits, he was involved in some of the greatest swashbucklers of all time, including the aforementioned Captain Blood where Peter Blood goes toe to toe against the dastardly Levasseur (see above) on the beach. That alone would put him on the list of great fight choreographers. However, he also did the choreography work for Disney’s Zorro TV show, so I owe him a great debt for instilling in me a love for flashy swordplay.

Cavens is followed by a dagger and epee match. That may sound strange to us today, but it was quite a rage back in the 20s & 30s. There’s YouTube footage of Aldo Nadi fencing with sword and dagger that you can see here. He taught this sort of fencing in France prior to crossing the ocean to New York.

After that, another exhibition of kendo, followed by a foil lesson with Henri Uyttenhove teaching and Helene Mayer as pupil. I’d love to be able to share a YouTube clip of that, but alas, no such luck.

Clearly Uyttenhove was familiar with the local kendo scene. That’s him on the left, using a sabre against a shinai. The people watching include H. G. Feraud, in the headband, who served as the master of ceremonies for this 1936 fencing spectacular.

After another sabre bout, a demonstration of sharp Japanese swords. It’s possible that the kendo guy up against Uyttenhove above is the same that put on this portion of the event, but there are spelling and legibility issues with the note on the back of the press photo above. So I can’t be sure.

When we get to #23, we have Ralph Faulkner up against John Ely. Faulkner was still representing the LAAC at this point in time which is interesting, but not as interesting as John Ely representing Victor McLaglen’s Light Horse Regiment. “What the hell?” you say? You read that correctly. Wikipedia describes it as a “riding parade club, a polo-playing group and a precision motorcycle contingent”. Founded by actor Victor McLaglen.

My all time favorite character actor Victor McLaglen, seen above with Cary Grant. McLaglen was a soldier and boxer before turning to a career in Hollywood. He’s got 124 credits listed on IMDB, so if you don’t know who he is you don’t watch enough movies.

McLaglen’s horse riding, polo playing, motorcycle trick riding club was a social organization that was for a short time wrongly accused of having facist leanings. Polo was one of the most popular of Hollywood elite pastimes, with players like Spencer Tracy, Clark Gable and Walt Disney. McLaglen’s group played polo and participated in local parades. I’m guessing they may have been seen in the granddaddy of SoCal parades, the Rose Parade, but I don’t really know. Surprisingly, the motorcycle wing is still in existence and still sporting McLaglen’s name. Go figure! This doesn’t help me figure out who John Ely was and why he was representing McLaglen’s group at a fencing exhibition. Nothing related to McLaglen’s group mentions anything about fencing, so perhaps Ely put them as his representative club as a bit of lark.

The final foil bout of the evening is an exhibition of foil mastery put on by Helene Mayer and Duris de Jong.

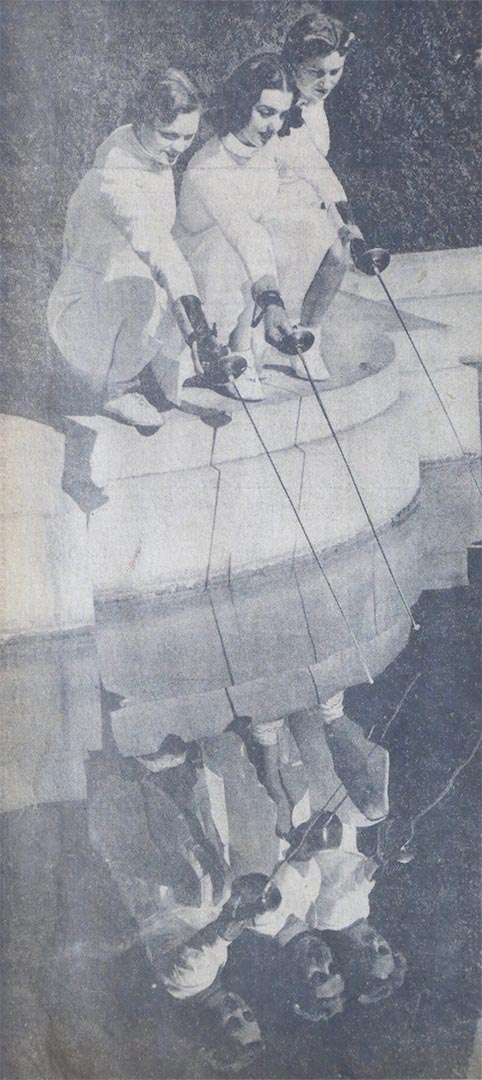

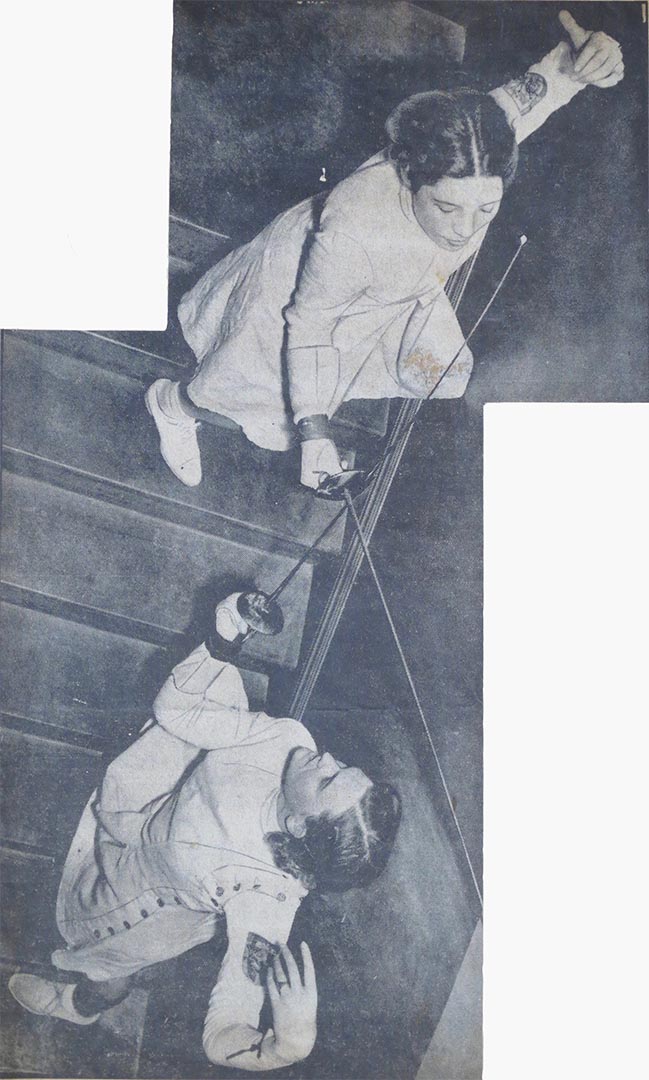

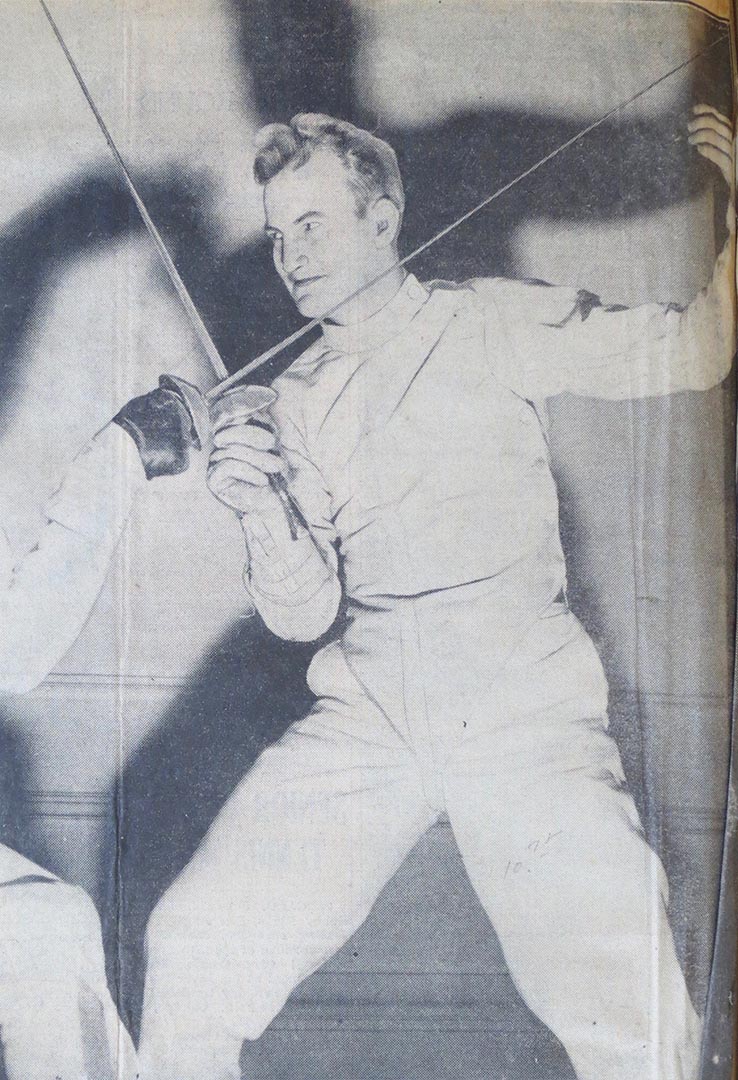

This article is from a few years before. 1934, I think. Helene Mayer did not often lose bouts on the west coast. It’s possible she never lost a bout on the west coast.

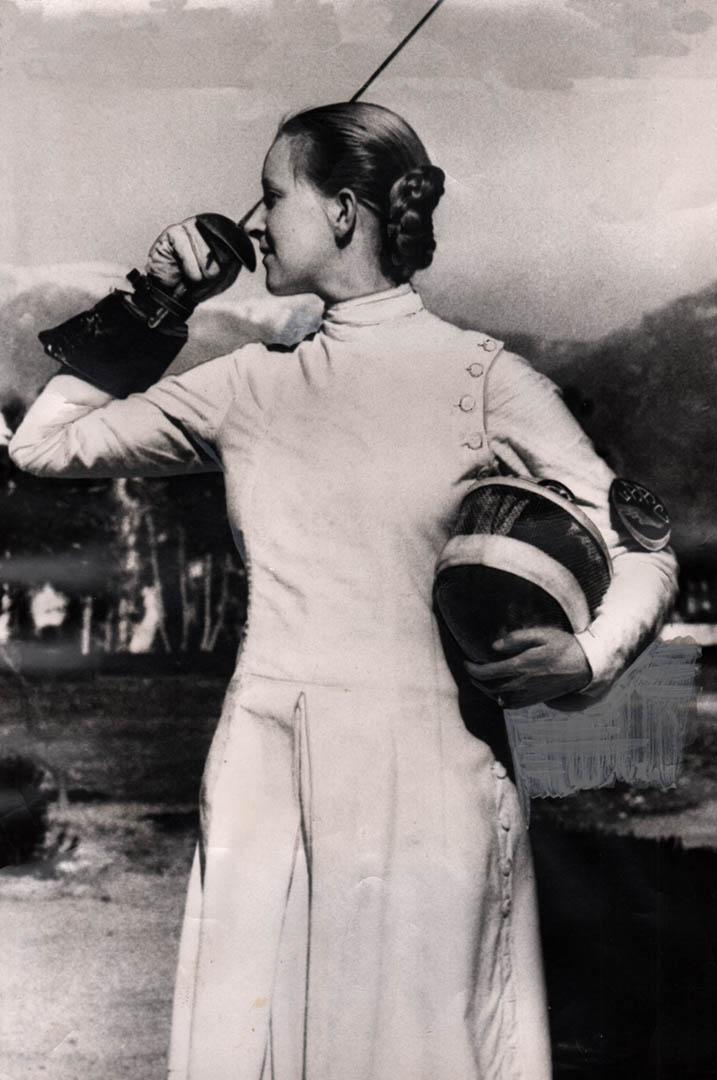

Because it was handy and I also did some photoshop work to clean this image up from some of the paint work done to get it ready for newspaper publication, I thought I’d add another Helene Mayer photo. In this one, she’s sporting an LAAC patch, the club she represented during her college days. She attended the Claremont Colleges in Claremont, CA, the next town over from my hometown of Pomona.

I’d love to know how Duris de Jong fared in a bout against Helene Mayer. By 1936 de Jong was doing more teaching than competing, while Helene was still waiting to learn if she would or would not represent her native Germany at the 1936 Berlin Olympics. She did, but that’s a story all its own.

The final event of the evening must have been a rousing and crowd-pleasing affair. They had demonstrated it earlier in the evening – the Balloon Sabre event – but for the grand finale, they use a team format. Now, there’s no way to know if they used a one-bout-at-a-time format, or a melee format. I’d like to imagine the latter. That is undoubtedly due to my having seen this:

As fun as that is, I just can’t end there. Fortunately, I have just the picture to wrap all this up.

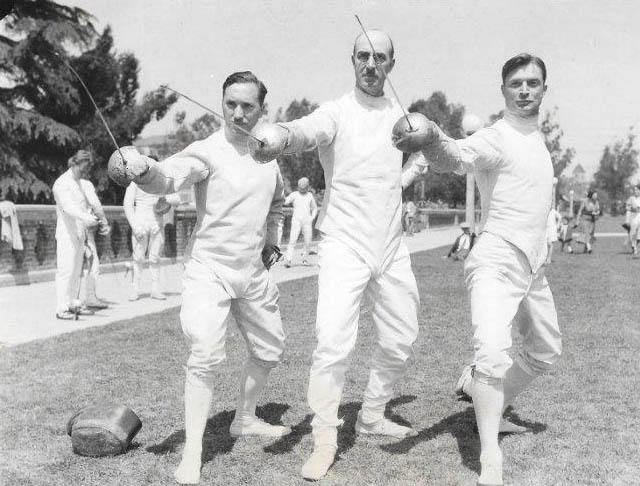

The above training session took place in the run-up to the 1932 Los Angeles Olympic Games. From left to right, Duris de Jong, H. G. Feraud and Ralph Faulkner. All three participated in the 1936 LAAC Gala Assault, two as fencers, one as master of ceremonies. All things considered, this would have been quite the spectacle to witness. One of these days I still hope to get down to the Los Angeles Athletic Club to go through their archives. This event is certainly one I’ll put on my list for researching. Who knows? Maybe they’ve got other documentation or photographs. I despair of any film footage, of course. Can’t hope for too much.

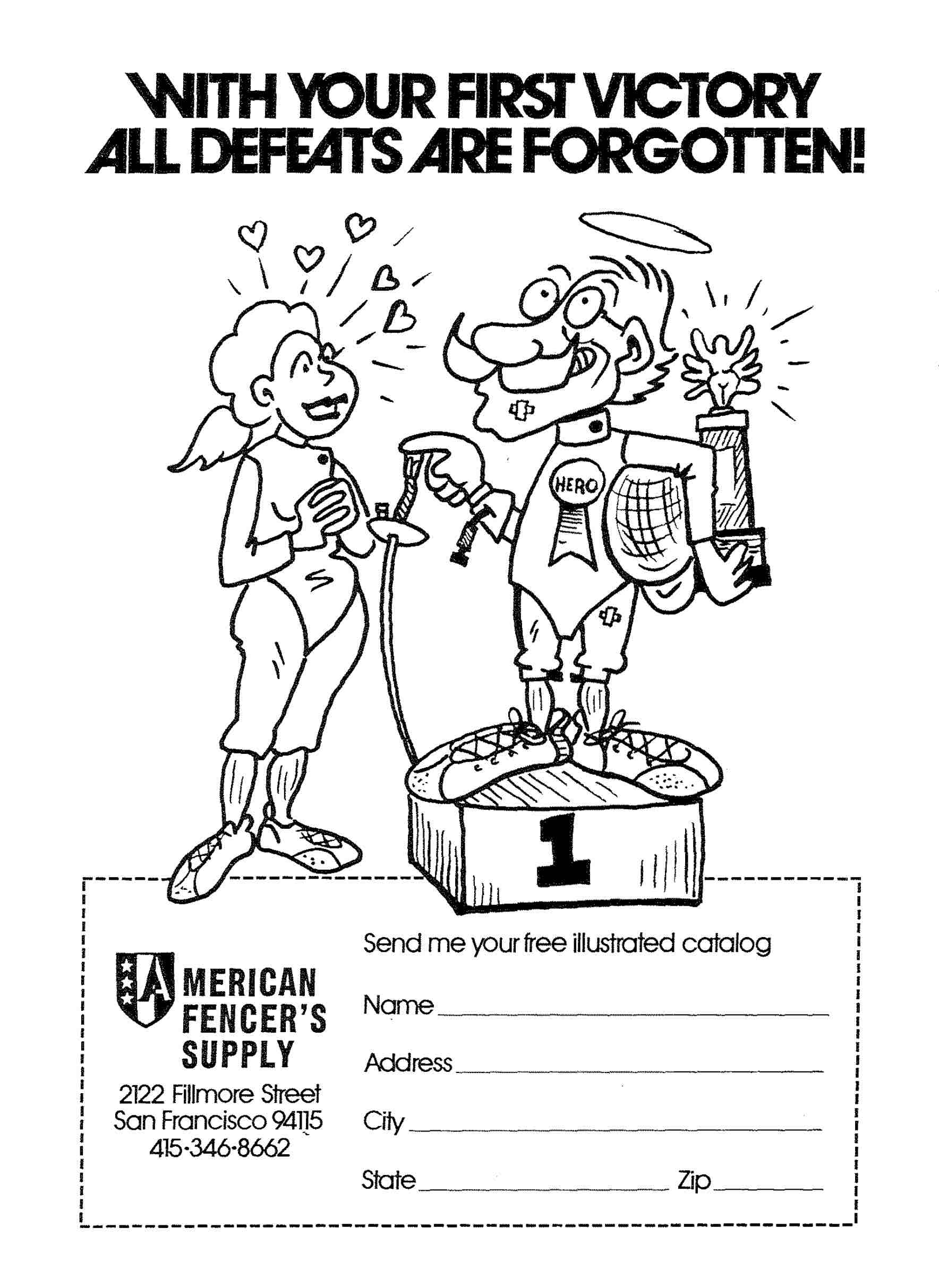

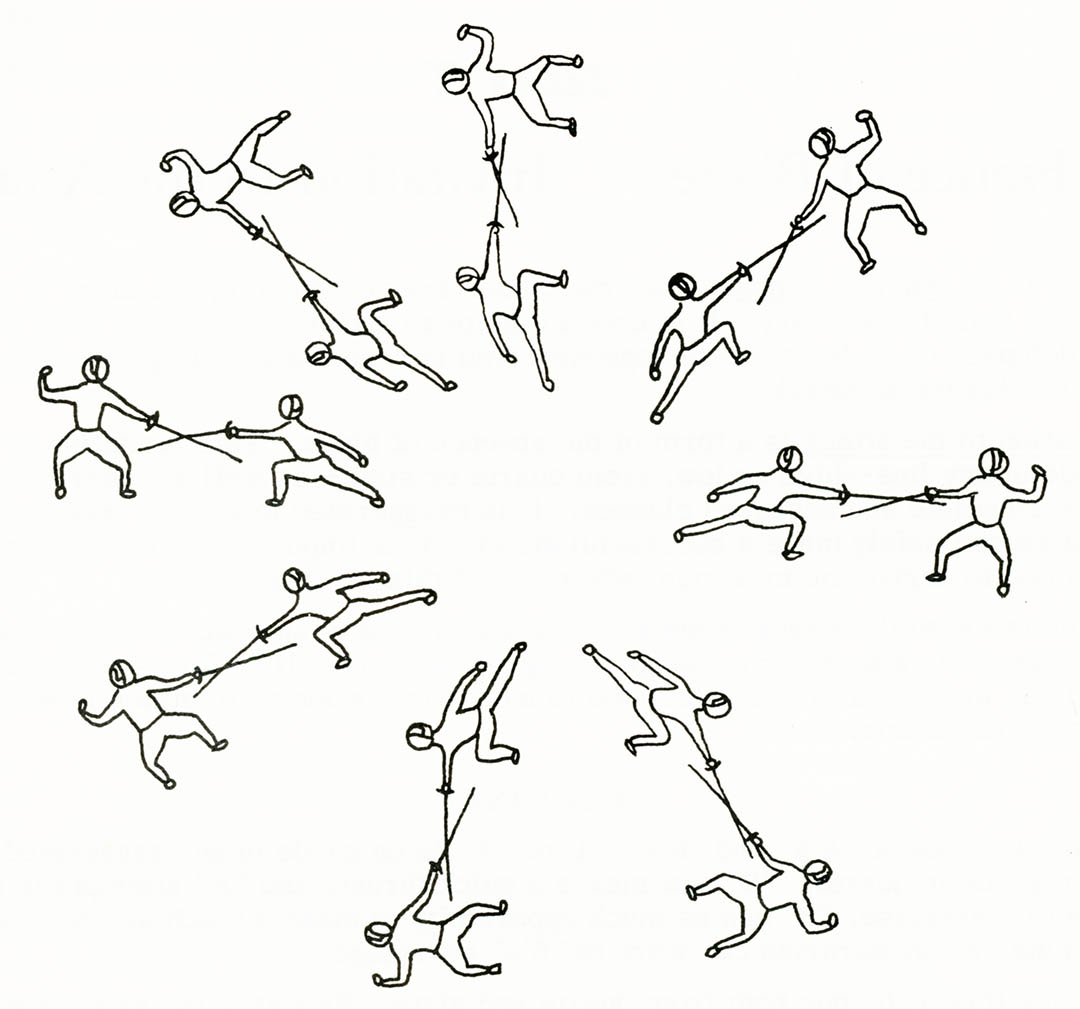

Cartoons by Selberg

Charles Selberg, or Charlie as he was more commonly known, in 1966 established the fencing program at UC Santa Cruz, home of the Banana Slugs. More, Charlie Selberg was an artist. He grew up in Fargo, North Dakota in a tough situation. His mother died young and his father, a police officer, took to drink after winning a shootout with a notorious bad man. By the time World War 2 came around, his father was gone and both of his older brothers were fighting in the war, one in Europe, one in the Pacific. Homeless for a time, Charlie fell into a job as a sign painter and also began designing title cards for industrial film maker Bill Snyder. In some more or less mysterious way, he wound up in San Francisco at SF State and got a Bachelors and Masters degree in Art. The fencing instructor at State was Erich Funke d’Egnuff, and he started Charlie on the path to fencer, fencing teacher, fencing master, fencing guru, etc.

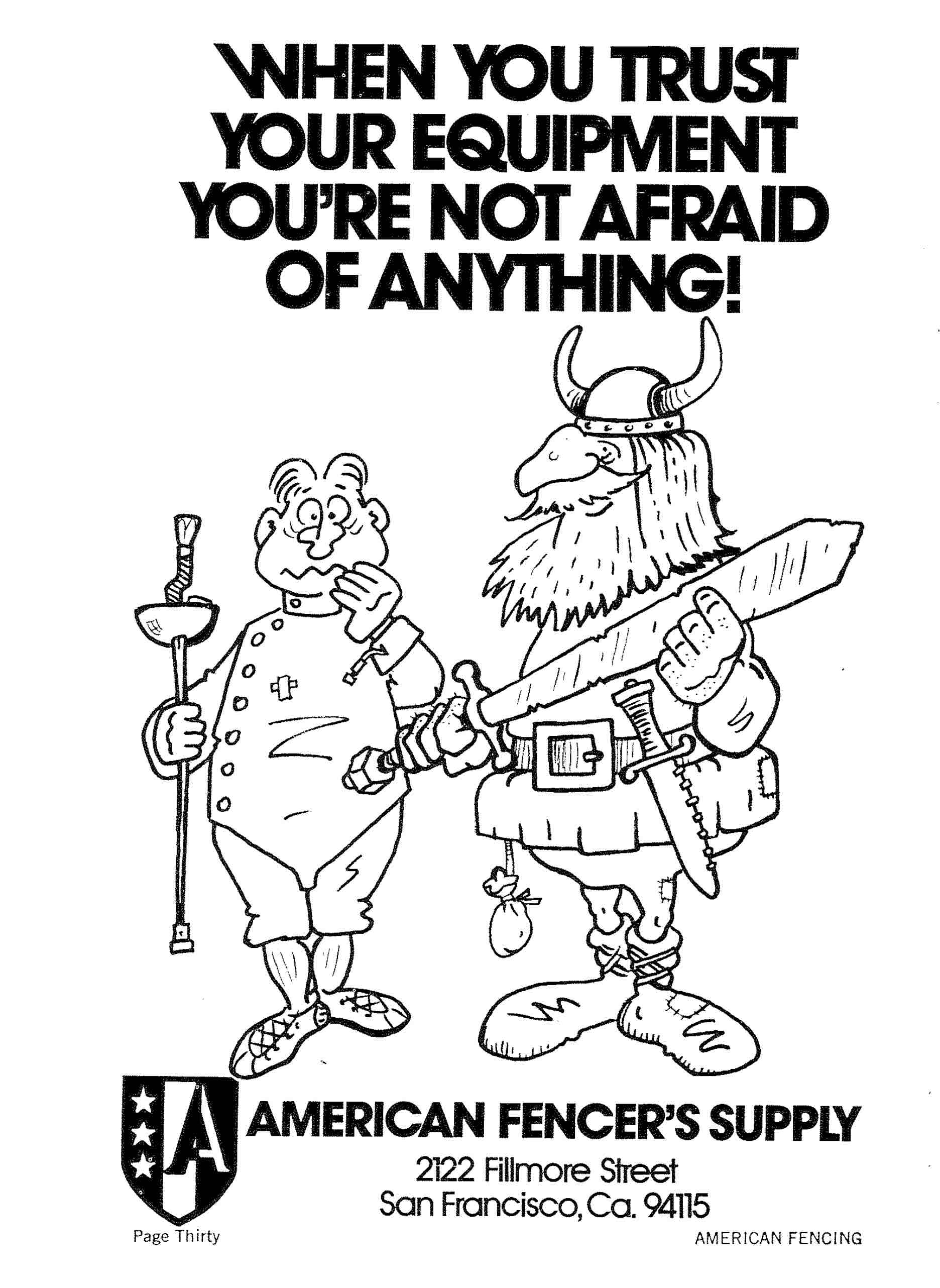

All that for background for today’s topic: Charlie the Cartoonist. In the mid-1970s, Charlie was producing cartoon art for the advertising that American Fencer’s Supply ran in the back pages of American Fencing Magazine. AFS was founded and co-owned by Charlie’s long-time friend, John McDougall. Whether it was casual assistance or a paying side hustle, I don’t know. (I trust John will fill me in.) I pulled some examples of these ads to give an idea of how AFS differentiated themselves in the market. No staid still-life with mask or crossed swords for the AFS ads. No, indeed.

Charlie was of Swedish heritage and the viking horned helmet, while not necessarily an historically accurate wartime accoutrement for your average sea-rover, was something Charlie was likely to don for jokey photo ops. So not really a surprise that he would include a viking in his art.

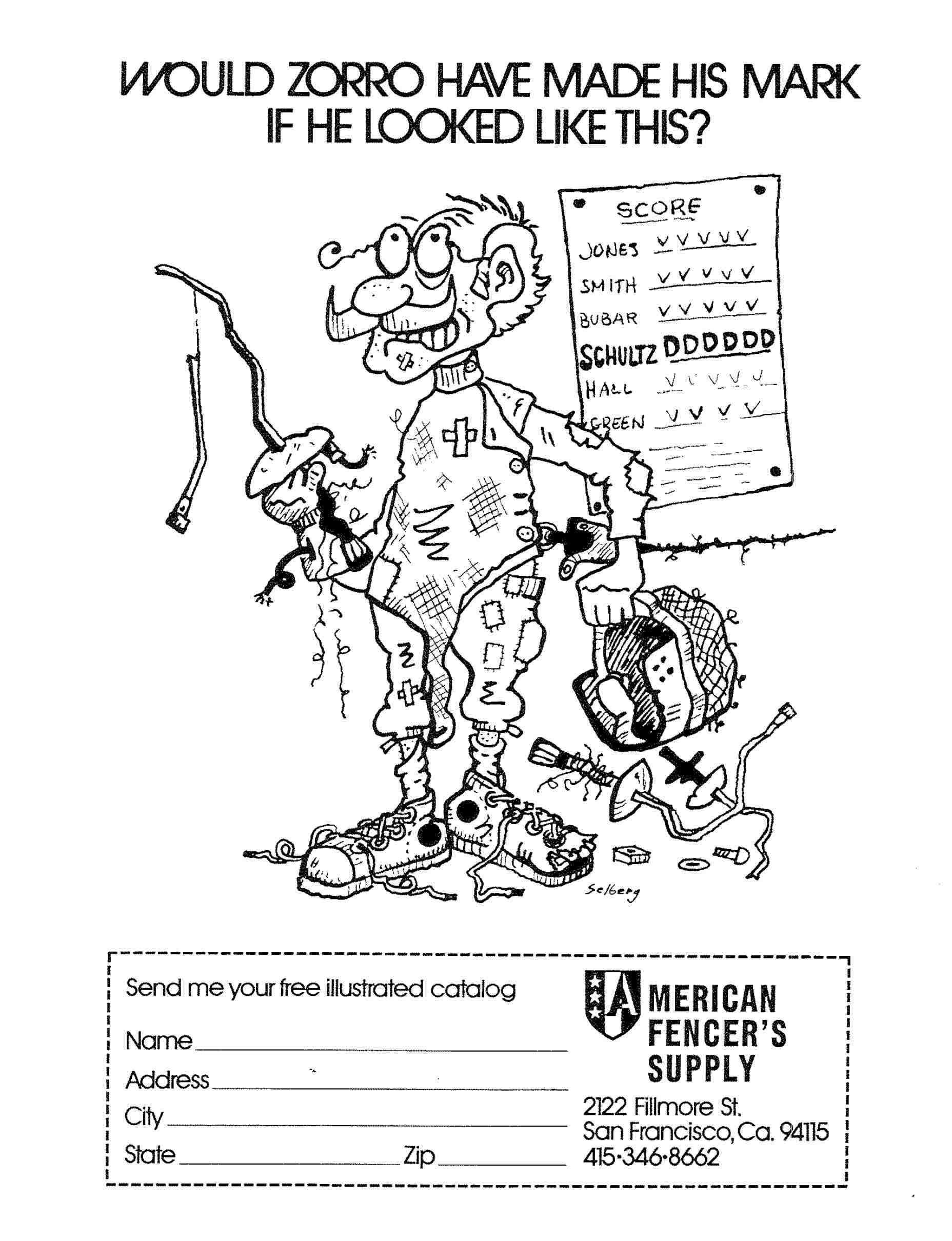

This one includes the name of the artist, signed near Schultz the Geezer’s left foot. “Schultz” was a recurring character as we’ll see in the next one. I particularly like the scoreboard in this one, with everyone but Schultz winning all their bouts while Schultz, with his poor kit, loses all of his. Here’s a final one:

Schultz the Geezer again, this time the winner. No doubt his victory can be directly attributed to his having purchased new gear from American Fencer’s Supply.

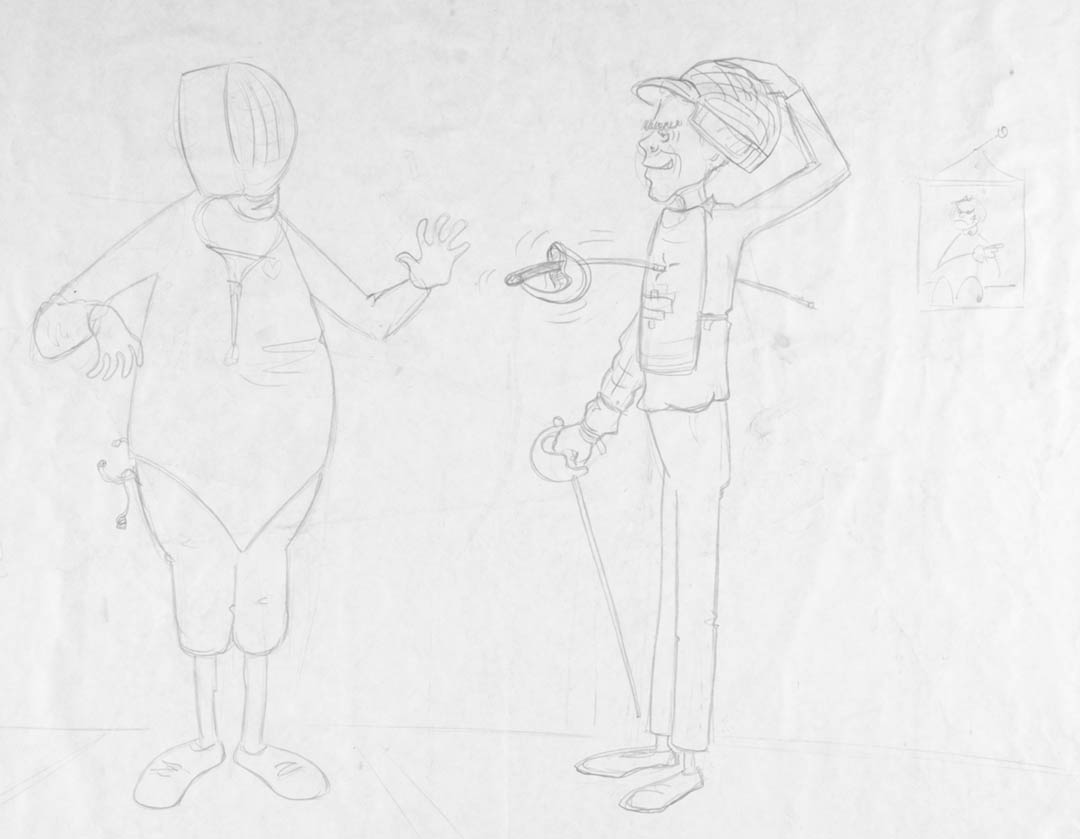

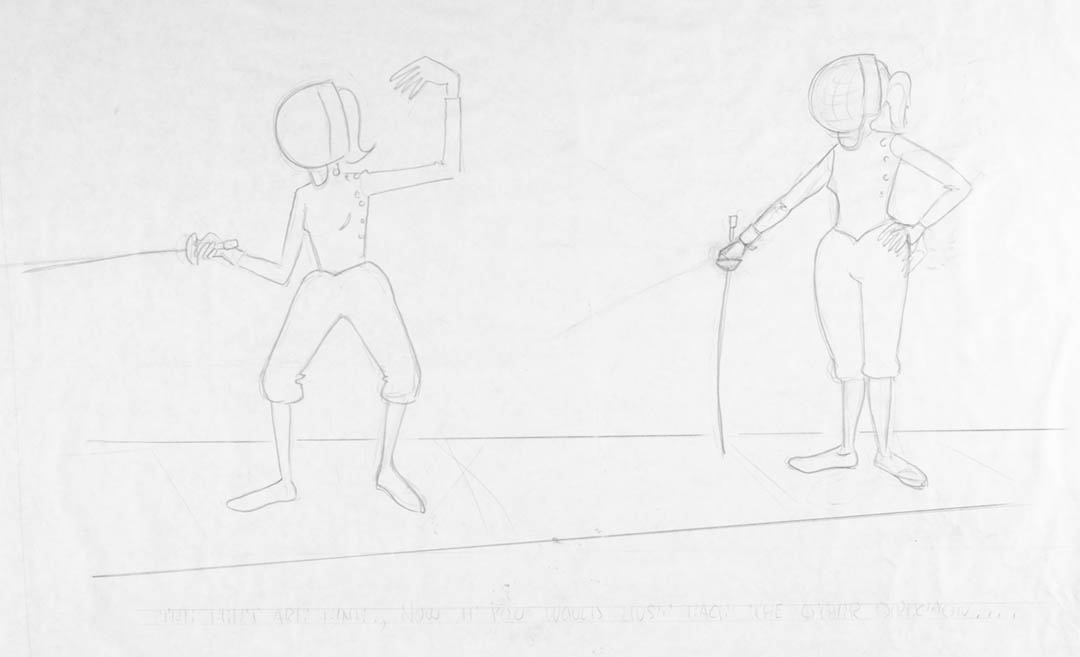

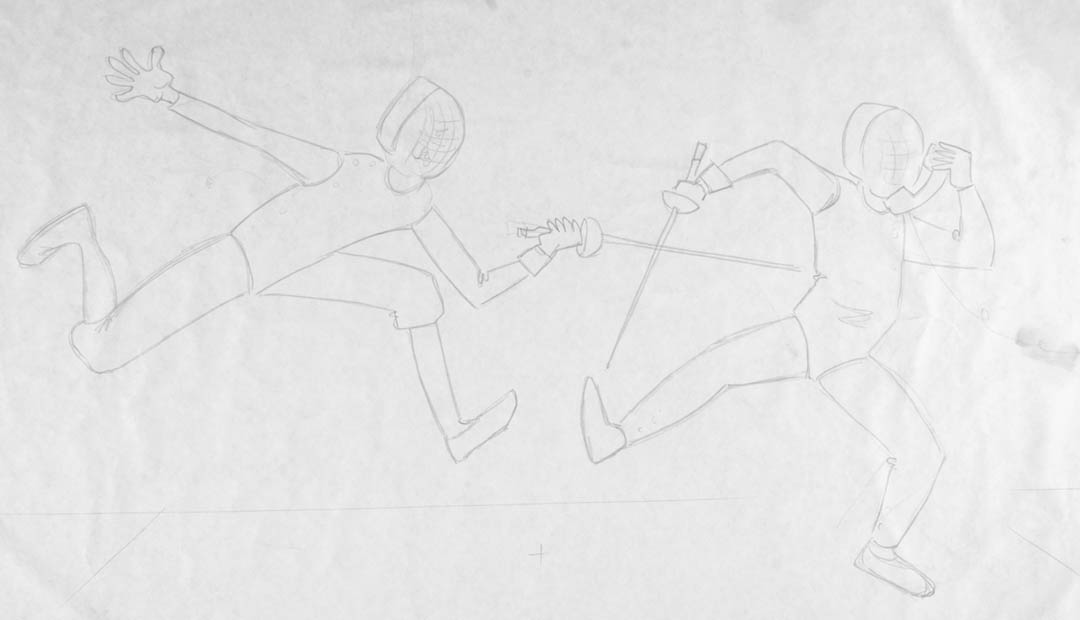

Now all that is prequel to what I actually wanted to share this week. If you’ve looked at the “Posters” section of this website, then you’ll know that we have a broad selection that includes local, national and international examples of fencing competition posters. Prior to putting these up on the site, I wanted to clean them up and make them look new. Since some of the posters, heck, really most of the posters, are too big to fit on my flatbed scanner (11×17 max), I worked with my photographer brother Garrett to shoot raw images that could be dropped into Photoshop and retouched. His studio had a large vacuum table that proved very handy for holding the posters in place without having to tape down corners or edges. Really handy tool. Wish I had one. Anyway, I took a bunch of posters down to his studio and we spent a couple of hours in the mode of set up, shoot, repeat. In addition to the posters, I also took down some large paper sheets that had original Charlie Selberg cartoon drawings on them. They were way too big for the scanner, but I definitely wanted to get some good images of them for some future use. I guess that’s today! They aren’t totally finished and some are further along than others, but they’re a fun lot and I thought y’all might enjoy seeing them.

Some of the drawings have captions, some don’t. All of the captions are hard to decipher, as they were never fully lettered. This one reads, to the best of my ability to interpret it, “How did this poor devil get frostbite during a fencing tournament?” I suspect, but can’t prove, that someone mentioned having cold feet to Charlie, with this as a result.

Of course, there’s no way for me to know if Charlie had some specific intent for the ultimate use of these cartoons. I know from looking through back issues of American Fencing Magazine that they sometimes included cartoons by other fencers and coaches who were artistically (and comically) inclined. I’m looking at you, Buzz Hurst. Whether Charlie was intending to participate in the fun or had some other idea for these, I’ve no clue.

As I mentioned, some of the drawings don’t have captions. However, some of them have caricatures! This seems to me to be an example of that. This caricature, though, is a bit of a mystery. It could be a self-caricature of Charlie. However, it also kinda reminds me of Ed Richards. Without a caption or some other hint, no way to know for sure. Anyone feeling a caption for this?

Another with a caption. This one was particularly tough to make out and I think it reads, “The feet are fine, now if you would just face the other direction.” It may not be exact, but it’s close.

This is the toughest one to read. Here’s my take: “If we put the whatchamacallit on the thingamabob, we’ll sew him up and send him back to the salle for another touch or two.” Best guess. I particularly like the ‘scraps’ box under the table.

No caption here, but in today’s world, this one is even more apt to be an actual event and not just a funny idea. Anyone yet seen someone take a phone call mid-bout? It’s just a matter of time.

Last one. Again, no caption. However, I do think this one is another caricature. Not for the musketeer, but rather the other guy pointing at the book. I’m going to say that’s a caricature of Erich Funke d’Egnuff. Whether this idea originated from an event of some sort, with a little embellishment of course, there’s no way to know. If Charlie ever explained these to anyone or even showed them off, perhaps someone out there reading can fill us in. Then again, he may have simply done the work, rolled them up and put them in a corner.

I don’t recall exactly where Mark and I found these drawings when we were taking Charlie’s salle down to preserve the contents for posterity instead of leaving everything to the mercy of Southern Oregon’s voracious rodent population. They weren’t on display, but rolled up together and stashed. They aren’t in great shape. (I did a little re-touching to post them, but not a ton. Mostly upped the contrast and brightness.) There’s quite a bit of wear on the ends and the paper has browned a bit, but the middles are in reasonable shape, so they must have been stored in a poster tube. Probably for a long, long time.

Helene Mayer Goes To Jail

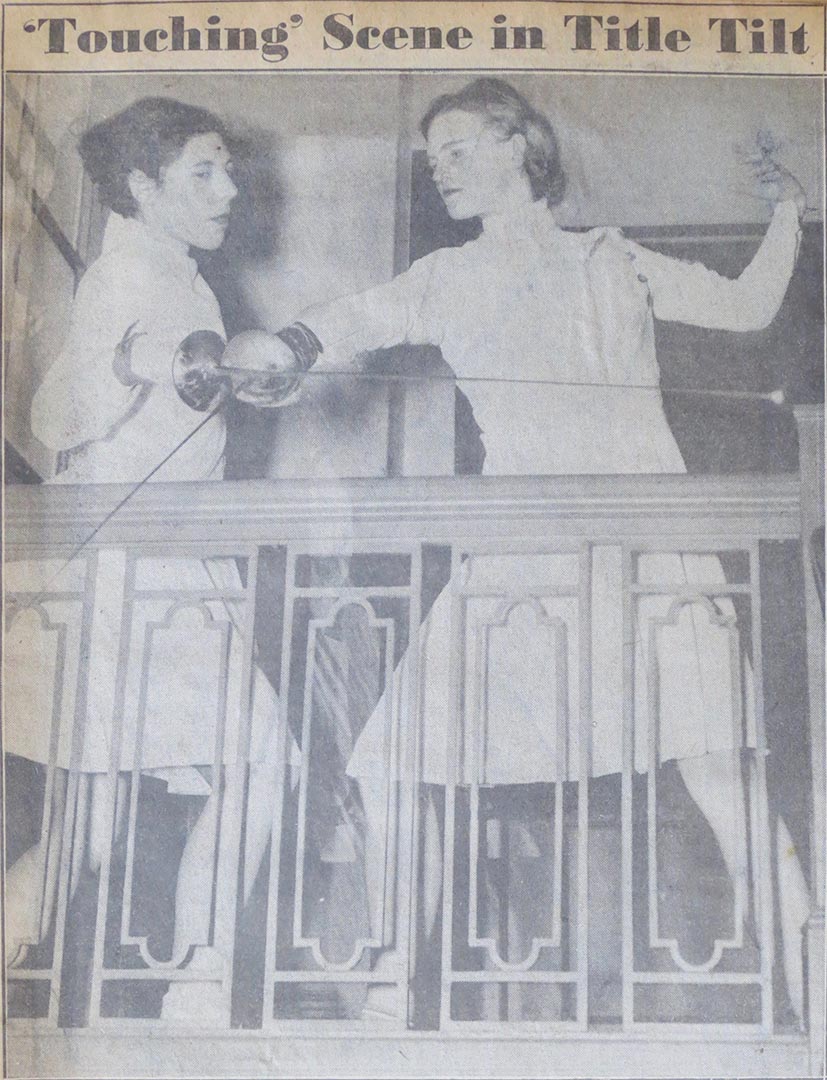

It’s a struggle to not take cheap shots at the drawings in old fencing books, at least for me. Sometimes though, the artist’s interpretation of the message the author is trying to convey is just too good to forego a bit of a laugh. Take the above photo, for example. Is Helene Mayer in really in jail? Probably not. And yet.

The book I’m referencing for today’s Fun With Drawings, is “How to Fence: A Handbook for Teachers and Students” by Frederica Bernhard and Vernon Edwards. Miss Bernhard taught at UC Berkeley for decades in multiple disciplines and was possibly better known for her work in diving safety than teaching Berkeley gals to fence.

I’m tempted to take this cover into Photoshop and make a poster of René Pinchart, longtime Maitre d’Armes at the New York Fencers Club.

The book was published in 1956 and in most ways it is a standard tome relating reasonably sound information on how to organize a class, bring along beginning students, and instill in them a love for the sport. That last is a subtly recurring theme throughout the book that the author highlights in various ways and is a sentiment that I’m all in favor of promoting. Where then, do I get off with my making fun of some of the illustrations in the book? What can I say. I’m a bad person. At least, that was the opinion my wife espoused when I showed her some of the pictures and explained my intent.

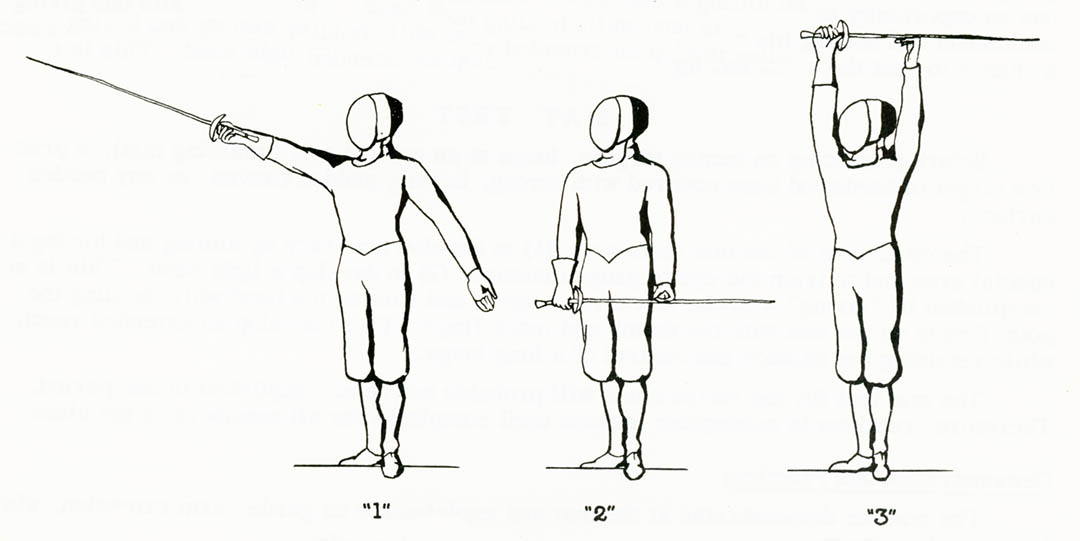

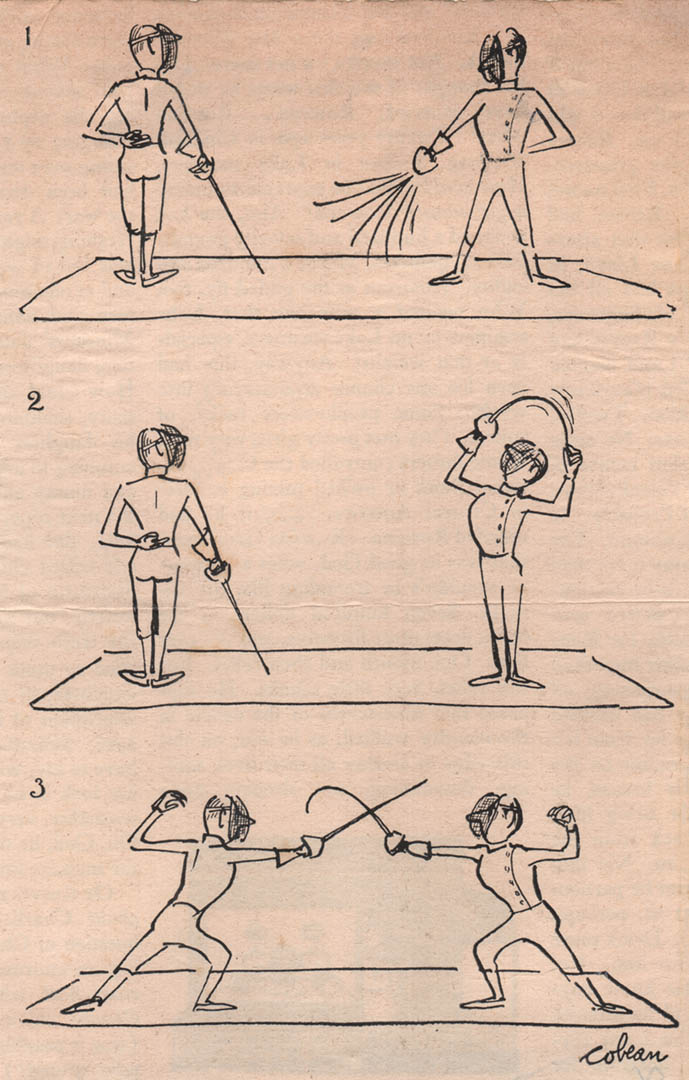

Let’s continue with the below example:

This is an excellent representation of How To Surrender in three counts. One, without taking a threatening stance, aim your foil well above your opponents’ head. Two, briefly consider the available options for escape if you decide to make a break for it. Three, offer the universally recognized posture of capitulation. White flag tied to the end of the foil is optional.

I’m not certain, as the book does not provide any clarity, as to who was responsible for the drawings versus text, or if both were jointly responsible. Or if both Bernhard and Edwards shared chores on the text and an unnamed artist did the drawings without credit. Another mystery, of sorts, stands in regards to Vernon Edwards. In his preface to the book, Maitre Pinchart references “Miss Bernhard and Mrs. Edwards”, which confuses me as to whether Vernon was her husband’s name or her own, as “Mrs. Vernon Edwards” would have been a common enough way for a woman to write “her” name in the 1950s. Not today, of course; well out of fashion. Whichever, Mrs. Edwards was a member of the New York Fencers Club, so coordinating efforts on the book would have been a back-and-forth progression via the United States Postal Service, no matter who was responsible for what in those long ago pre-fax-machine days of yore.

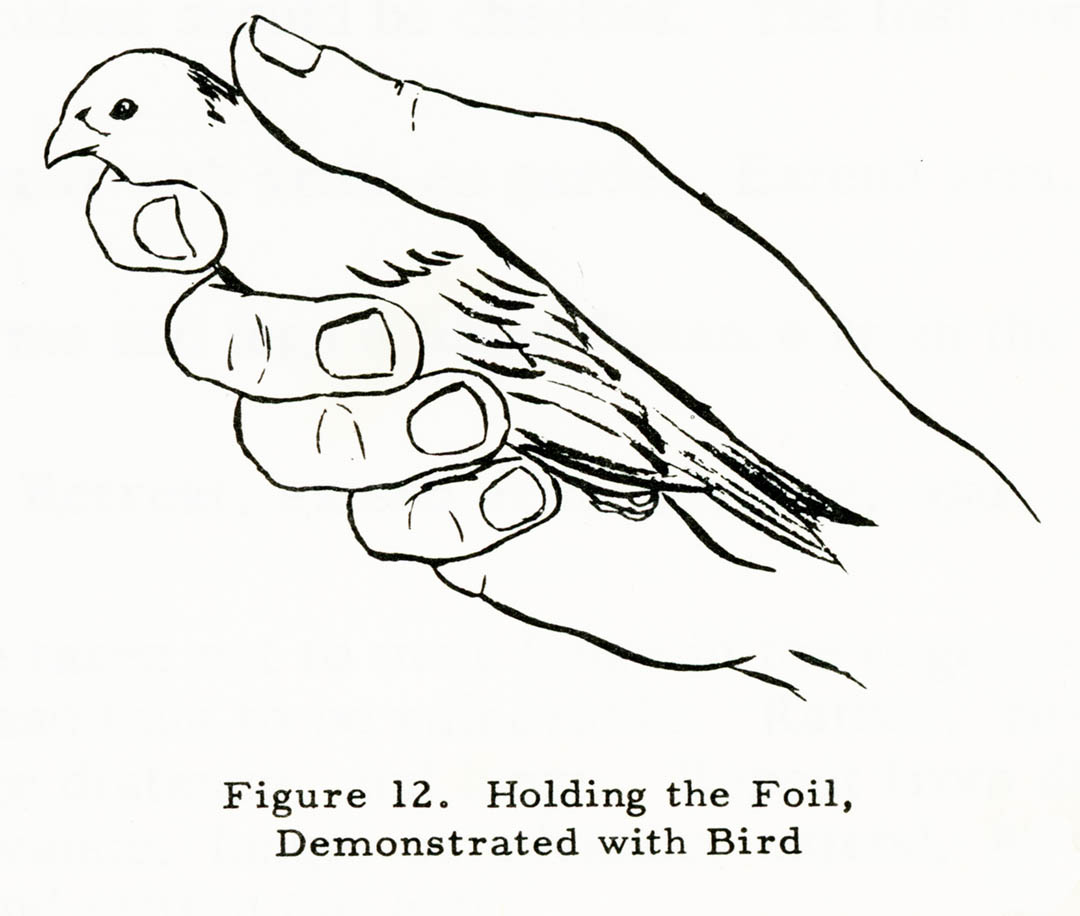

We’ve all heard it. Some of us (guilty as charged) have said it. Finally, here is the definitive visual example of what exactly is meant when describing the holding of the foil, as compared to holding a bird. You know this old chestnut: tight enough so that it doesn’t get away; loose enough that you don’t murder the sparrow in your hand. Something like that. Of course, it might not be a sparrow. Could be a finch. Or a European swallow. Without a color photograph to get a look at the beautiful plumage of the captive avian, it’s impossible to know.

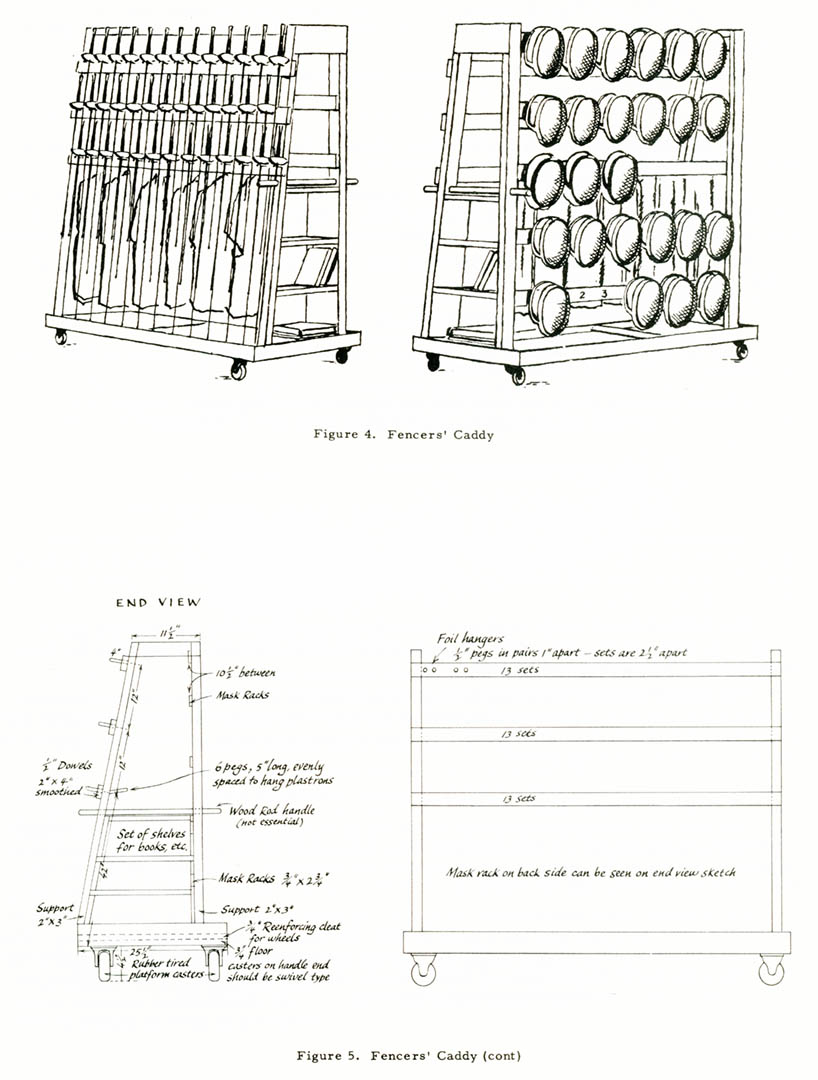

Because the book was meant for teachers as well as students, it provides some useful examples of things an inexperienced teacher or someone starting a program from scratch might require as an aid to organization. Indeed, there are lots of descriptions on what equipment to provide for a class, how to care for it, workarounds when you don’t have enough jackets or plastrons, etc. One of the more interesting to me is this example of a rolling cart that you can build at home with spare lumber and a few things from the local hardware store. Here’s the whole plan, including measurements:

This thing is awesome! It will hold 30 masks, 39 foils, has interior pegs where you can hang jackets or plastrons to dry and a bookshelf. Actually, several bookshelves on each end of the structure. If anyone needs the plans, let me know. I can email you a higher resolution image of the diagram.

Cleanliness is another theme featured extensively in the book, with recommendations about several ways to avoid the spread of germs. Much advice on the advantages of the removable, washable bib, which is now illegal. Here though, students are advised to purchase their own bib for which they can bear the washing responsibilities. Barring that, wearing a barbershop-style neck tissue is recommended to keep neck germs off the bib. No, seriously, it suggests that. Washing the mask of anyone who has a cold immediately after class is highly recommended. And, ok, that’s not actually a bad idea. Washing masks weekly is also suggested with a warning of ensuring that they dry completely to avoid rust. When gloves are used in multiple classes, it is recommended that students purchase a washable cotton glove that can be worn as an extra layer inside the fencing glove. It goes on to say, “These cotton gloves have unfitted thumbs and can be worn on either hand, so two students can divide a pair as only one glove is needed.” There are also washing instructions and a debate about whether to iron your jacket or not. No definitive answer to that one, but fencing knickers should, indeed, be ironed. There’s a bit of a germaphobe/OCD feel to some of the suggestions. Or maybe I’m just too casual about environmental cleanliness.

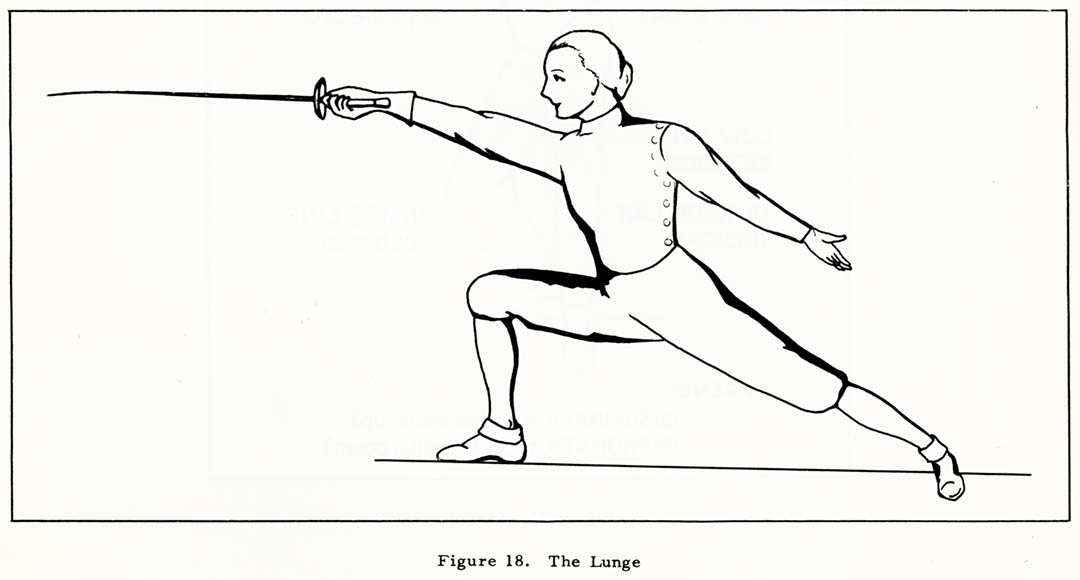

This drawing may well have been traced from a photograph of Helene Mayer. Miss Mayer and Miss Bernhard were acquaintances at the very least and partnered on a film about fencing basics that was made at UC Berkeley in 1942. Miss Bernhard’s name isn’t in the credits, but it does reference the UC Berkeley Physical Education Department for Women. That was Miss Bernhard’s bailiwick. You can see the film here. Interestingly, Miss Bernhard partnered on another book, titled “Educational Films in Sports” in 1946, and this 11 minute film of Helene Mayer is the only educative fencing film referenced.

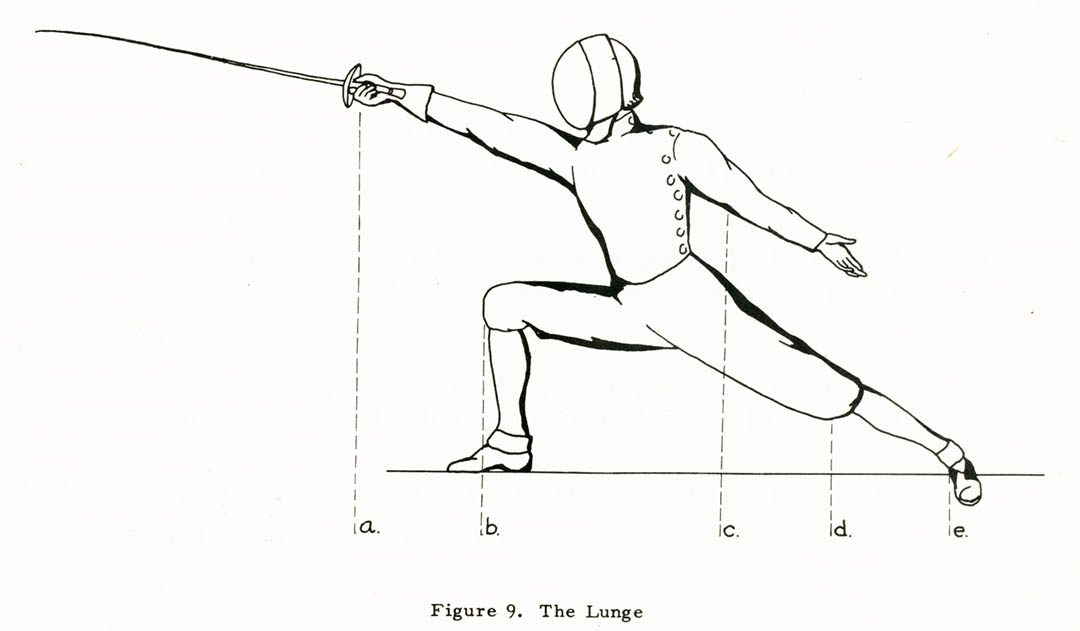

The influence of Helene Mayer on, at least, Miss Bernhard’s ideal perception of fencing form is probably best displayed in this drawing:

That’s essentially the same draw-over as the earlier lunge, but this time with a more Helene-like visage and the hair pulled back in a bun, a frequent feature of Helene’s hairstyle. In her younger days, she actually tended to sport a more Princess Leia-like ‘do’ with buns over each ear. Still. That’s her, even more than the drawing of Helene in jail that I led off with. (It’s not really her in jail. For anyone that was waiting for me to explain that.)

Toward the back of the book, there is a listing of a number of games that can be played in group class settings. There’s “Touchers Keepers” where you attach candy to the jackets of fencers and if one fencer can touch their opponent’s candy, they win the candy. Yum! Also a white-elephant style game titled “Grab Bag” where you fight for first dibs on wrapped gifts that all the fencers have contributed as an entry fee. Interestingly, she also describes a slightly altered version of the “Patri” game I’ve mentioned before (here) called “Captives in the Calaboose”, with a footnote that Giacomo Patri, namesake and originator of the idea, approved the changes to his game.

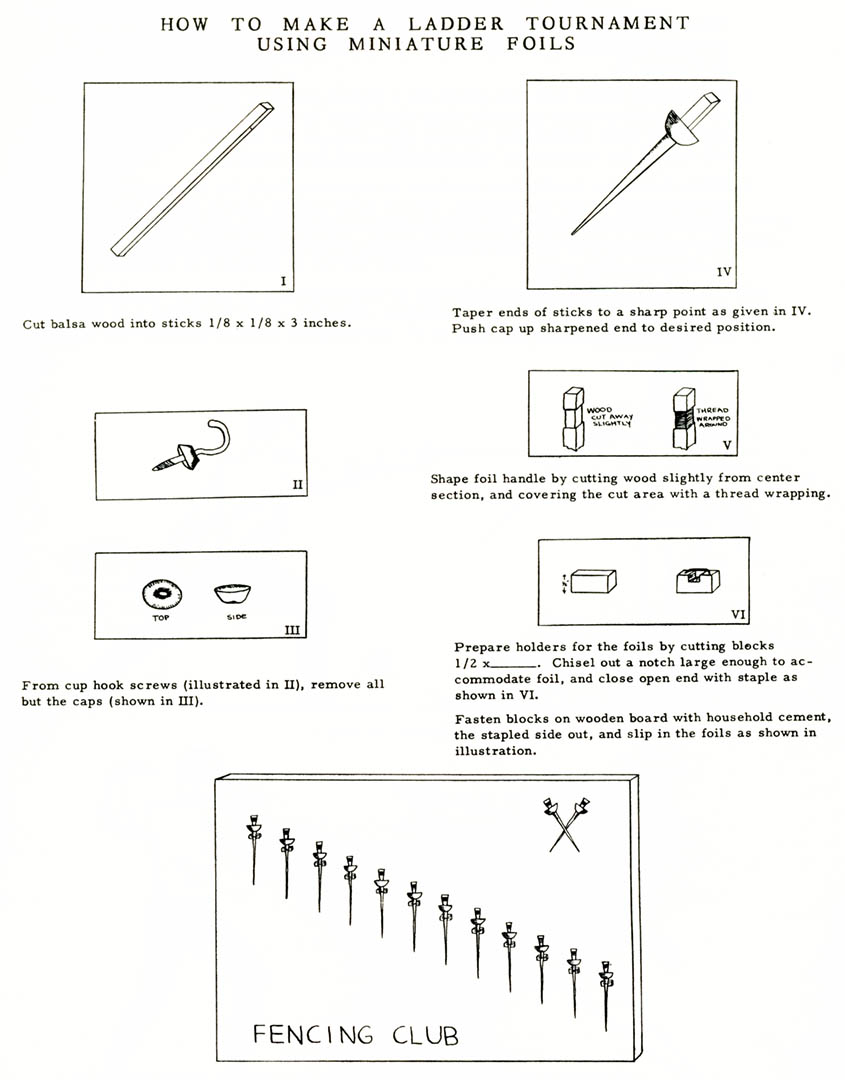

Here’s another project for you crafty and handy types. It’s for another fencing game, The Ladder Game, and the description says you put a name on each foil and fight for the supremacy of the top position by challenging other fencers and taking their spot. You work your way up by challenging anyone within 3 places of your position, having drawn lots to get the initial placement. Fighting continues until all parties are exhausted. Anyway, you can build it yourself!

This next one bears some explanation, but you can make up your own story first:

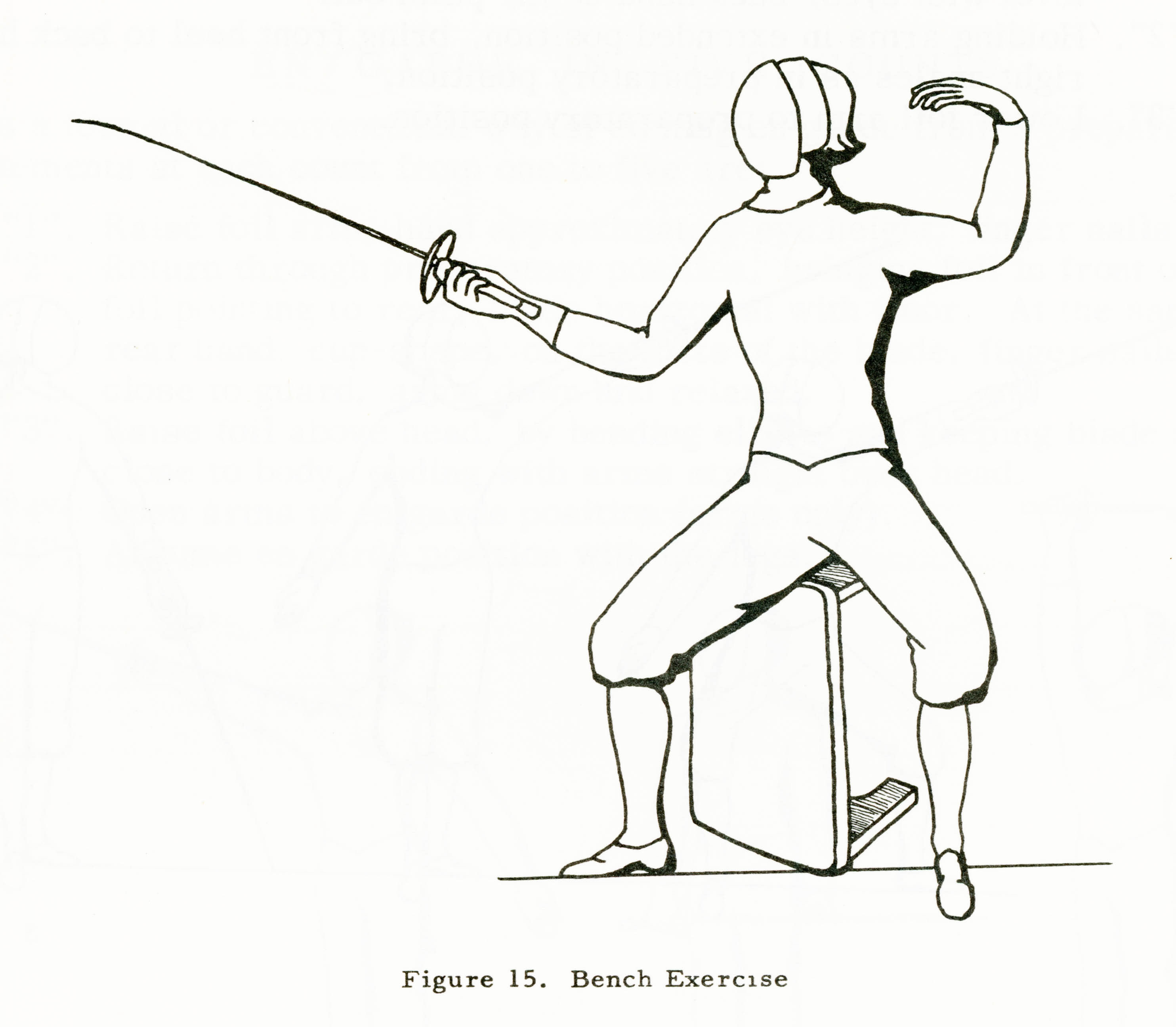

Is this not the perfect exercise for the Laziest Fencer in the World? Not that I know who that is, although at this particular moment I think I would, myself, give most people a run for their money. No, this is, in fact, an exercise designed to improve the on guard posture of your students. Got a fencer who’s too scrunched up? Feet in the wrong place? Doesn’t sit low in their guard? Well, provide them with a nearby bench, stool or chair of just the right height and watch those problems melt away! There aren’t any designs in the book for creating an adjustable height devise to aid instructors in providing this level of student assistance. You’ll just have to wing it.

As mentioned above, this book is designed to be used by teachers and fencers, both. The target audience as far as teachers go are those without a great deal of experience in the sport. And really, it’s a handy guide for generalist physical education instructors who work at a place with a pile of fencing gear sitting around gathering dust. Through use of this book, you could, with a minimum of fencing know-how, design a curriculum that would get you through a semester of beginning fencing without much difficulty. There’s just enough information for a teacher to put together a set of lesson plans that would take students on a well-organized walk-through of the basics of the game. The emphasis is on posture, body position, movement and not taking it all too seriously. It’s clearly not trying to create fire-eating competitors right out of the gate, so for what it’s attempting, it’s actually a pretty decent overview that could be followed easily enough.

The most entertaining reading comes in the directions for keeping your gear clean. The best examples are:

Knickers: Trousers should be laundered and ironed frequently.

Gloves: Smooth out wrinkles after the glove has been worn.

Socks: Socks should be washed frequently.

And finally: Underclothing should be worn at all times.

TMI? If that’s all starting to make your head spin, how do you think the below will go over?

I get the idea of this, but I can’t see how it’s better or more efficient that the usual linear line up you’ll see in pretty much all fencing classes everywhere. The description of this layout for class instruction gets a little lost in itself, I think. It can be found in the section on ripostes, but the exercise as described is: fencers salute, go on guard, then the outside circle rotates. Repeat until back with your original partner. I can’t help but think they meant to explain a slightly more complex drill. Still, there’s no reason you couldn’t set up class like this, changing partners by rotating around the fencers on the inside of the circle, assuming you’ve got the room for it. It does seem like it would eat up a fair bit of floorspace.

So that’s How To Fence, circa 1956, with some highly entertaining and educational illustrations. There are certainly fencing books of more modern vintage with a lower quotient of useful information in them. At the very least, that bench exercise is going into my repertoire as soon as I find something the right height upon which to park my tuchus!

My Forever Summer

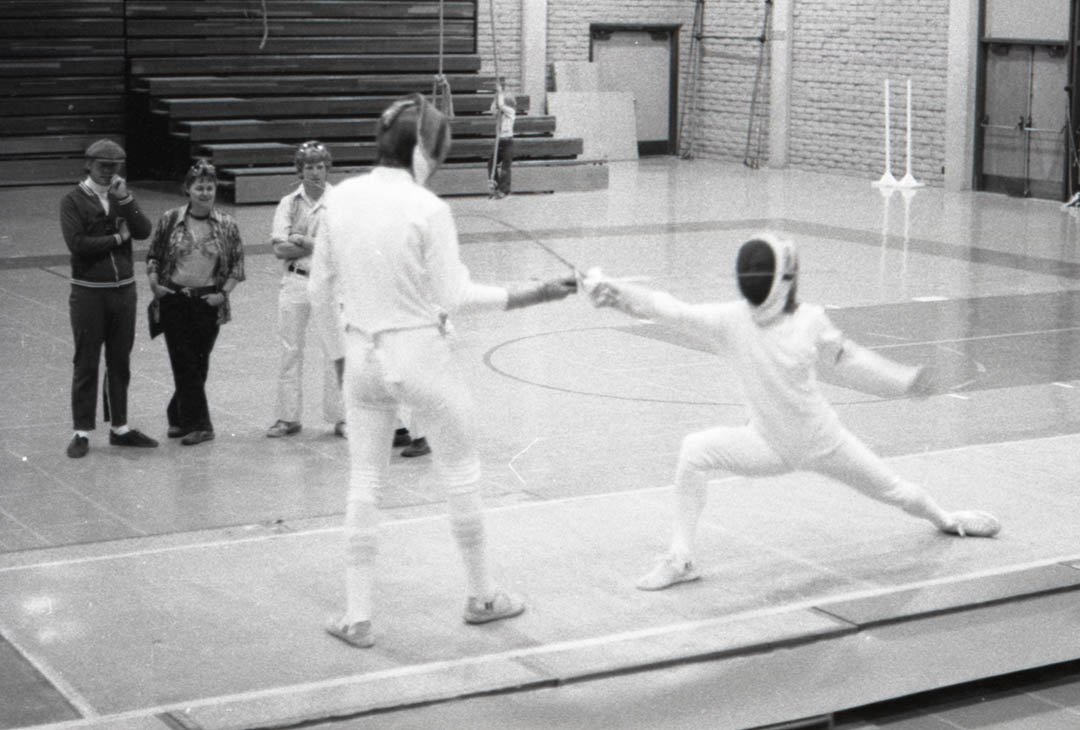

You don’t forget your first team, or your first teammates. The fortuitous circumstances surrounding my introduction to fencing couldn’t be more memorable; a time filled with remarkable personalities. Fencing was my first college course. Fencing, the game I’d always wanted to play, was finally right in front of me. A high school chum had taken some courses at our local community college, Cabrillo, during our senior year, one of which was fencing. Knowing that was my destination to start college and that they offered the sport I’d been intrigued with since elementary school, I had 1/6th of my first semester schedule selected before looking at the course catalog. And fencing was literally the first class, 8am Mondays and Wednesdays, so that first Monday of class, I found myself here:

Fifth in from the left. That’s what a beginning fencing class looked like in the 1977 of Santa Cruz, California. Len Carnighan looks very proper there on the far end. My good friend – still – and toughest bout in the class, Debra Allen, is on the left end.

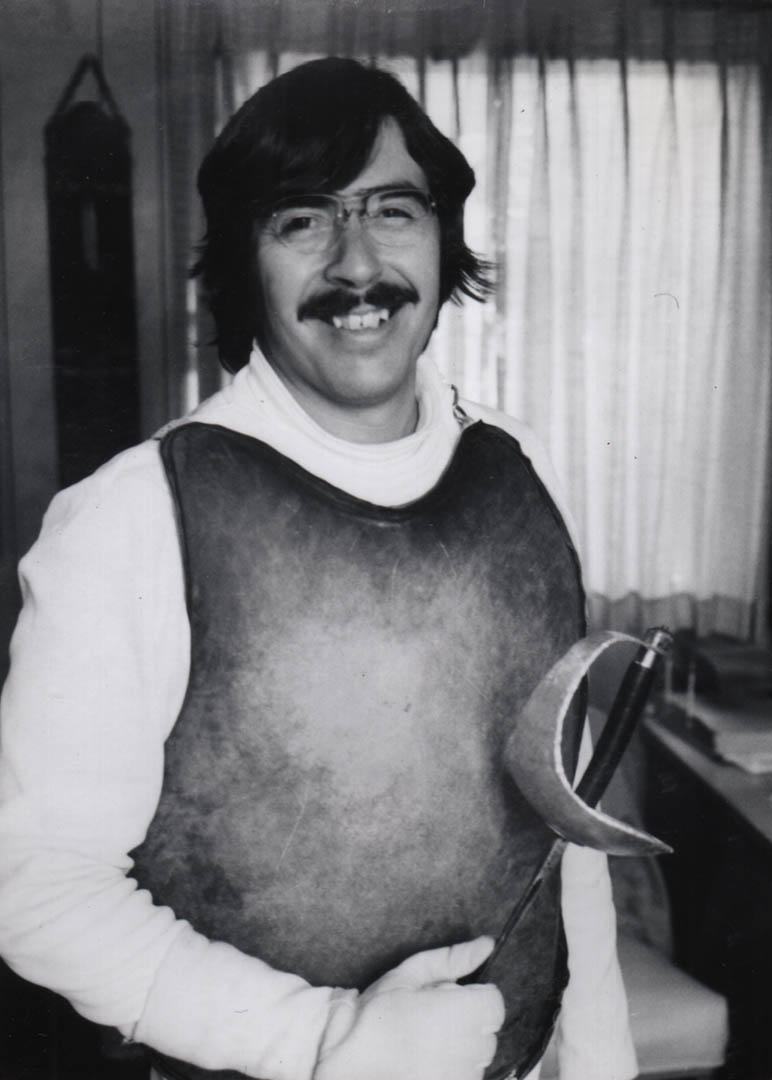

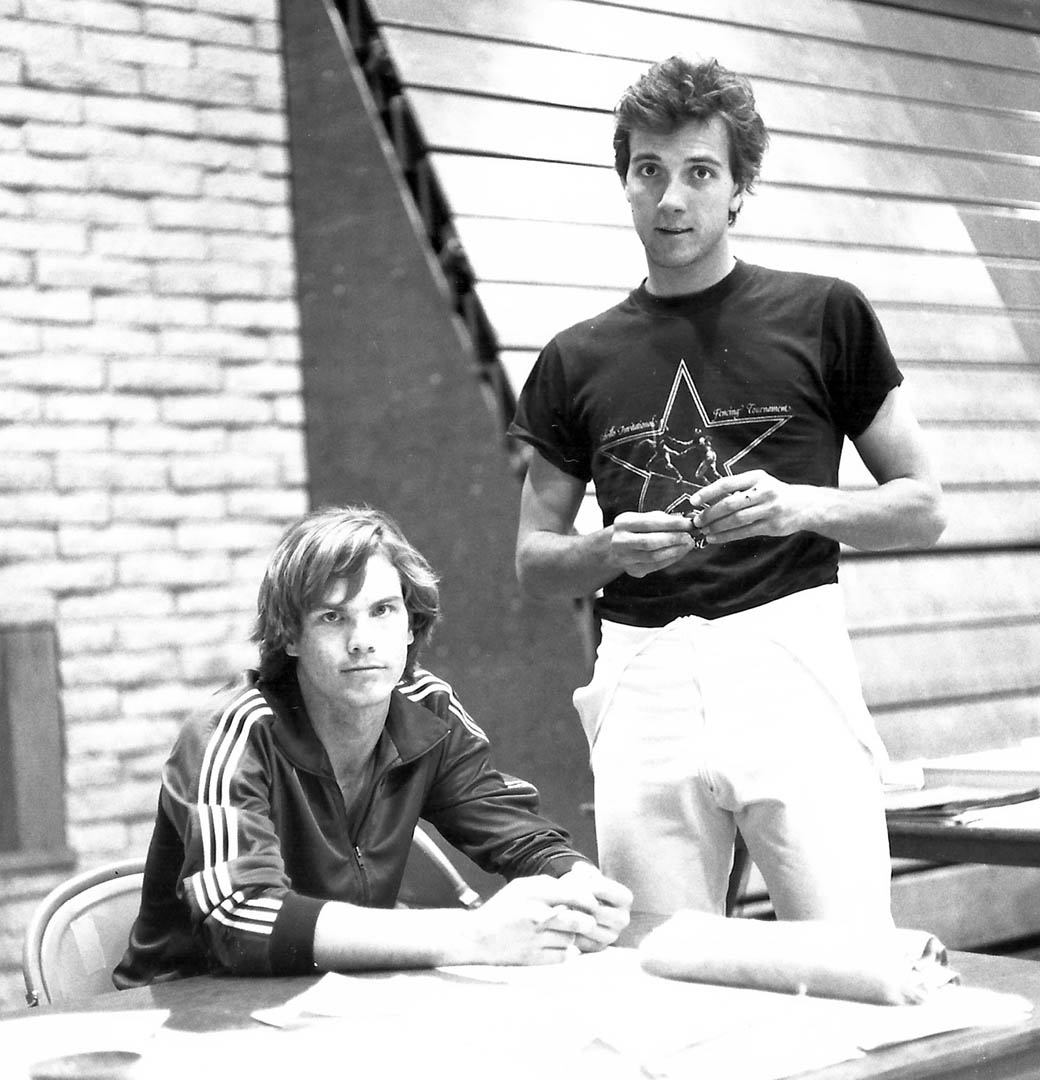

Len Carnighan was teaching his first college course that day. He had inherited the program from Darlene James who had taught at Cabrillo for some time, but was moving up to be an administrator and couldn’t continue teaching. She sought out advice from Charlie Selberg at UCSC, who recommended Len for the job. Len had attended UCSC after a year or two at LA Valley College, where he first learned to fence. His coach there, Joe Abel, recommended that he look into attending UCSC and learning from Charlie. Len took his advice and during his second year there, decided he wanted to dedicate his life to teaching fencing. Charlie taught and mentored him, sent him to Michael D’Asaro for additional tutoring, hooked him up with Jack Nottingham, who was one of Charlie’s formative teachers and recommended him to John McDougall as an assistant at John’s new club, Freedom Fencers.

Young Len Carnighan, fencing coach.

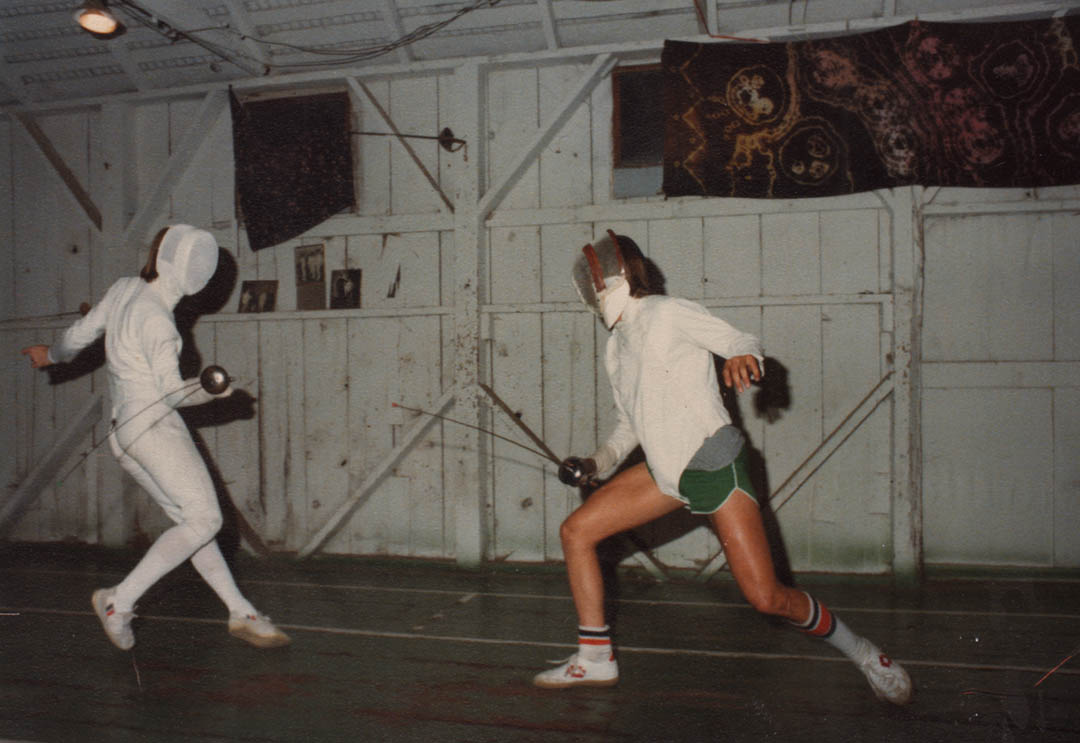

When I started at Cabrillo, Len had just taken over the Freedom Fencers Club from John. Now, if you think it was called the Freedom Fencers club as a statement of wrapped-in-the-flag patriotism, I can tell you, it wasn’t. The building it was in was an ancient hay and feed barn that had been repurposed by John, established in the dinky community of Freedom, California, on Freedom Blvd., the connecting thoroughfare between Aptos and Watsonville in southern Santa Cruz County. It had four short strips, two on a warped concrete slab and two on 2×6 painted boards, scarred and pitted, with half inch gaps between, that were, if anything, harder than the concrete.

*sigh*… That’s me on the left, sometime during my second year at Cabrillo trying to get away from my teammate, Kevin Kelsen. If I remember correctly, this photo was taken shortly after Len had returned from seeing – and videotaping – the Junior World Championships at Notre Dame in 1979. Len was watching us “fence” while basically standing in one place. He stopped us, reminded us of the tape he’d shown us from the Jr. Worlds and asked why weren’t we try to incorporate movement like we’d seen on the screen? This was our attempt at movement. *sigh*

As you can see from the above, it really was a ratty old barn. The paint was coming off the floor, the interior walls were full of spiderwebs and Len had yet to learn how to decorate a fencing club. And I don’t know what intergalactic force makes old wooden floorboards take on the quality of iron, but these boards had that quality. Those were some really hard oak beams. When Len taught me to fleché, I wasn’t getting it. I was too concerned with catching myself with my crossing foot. Frustrated, he finally yelled, “Stop trying to catch yourself! Just land on your face!” I was 19, so I did just that, fleching for all I was worth, fully stretched out. He was, I think, shocked that I’d actually done it, me face down on the floor learning just how hard oak can be. I think I completed a full-body rebound bounce. Still, I’d hit the target. My fleché improved markedly after that.

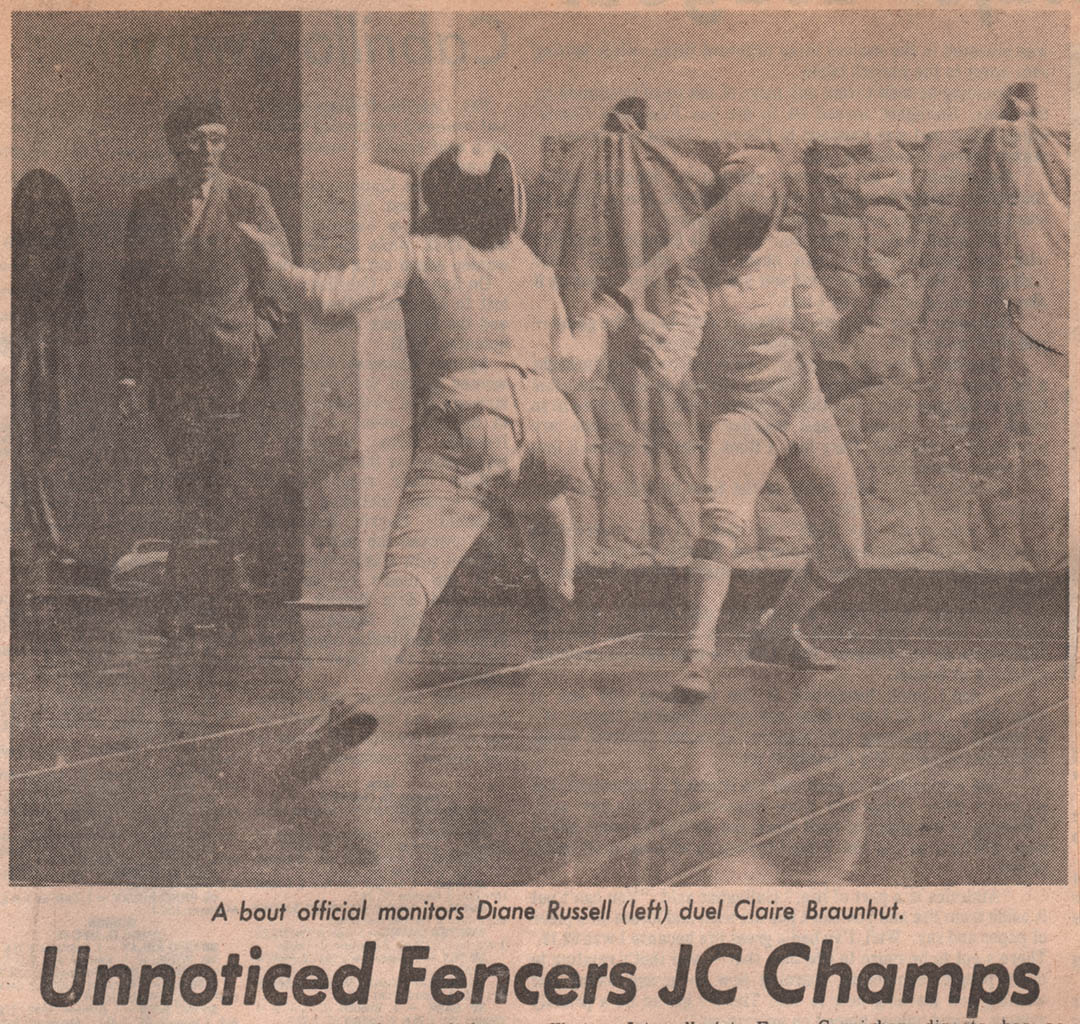

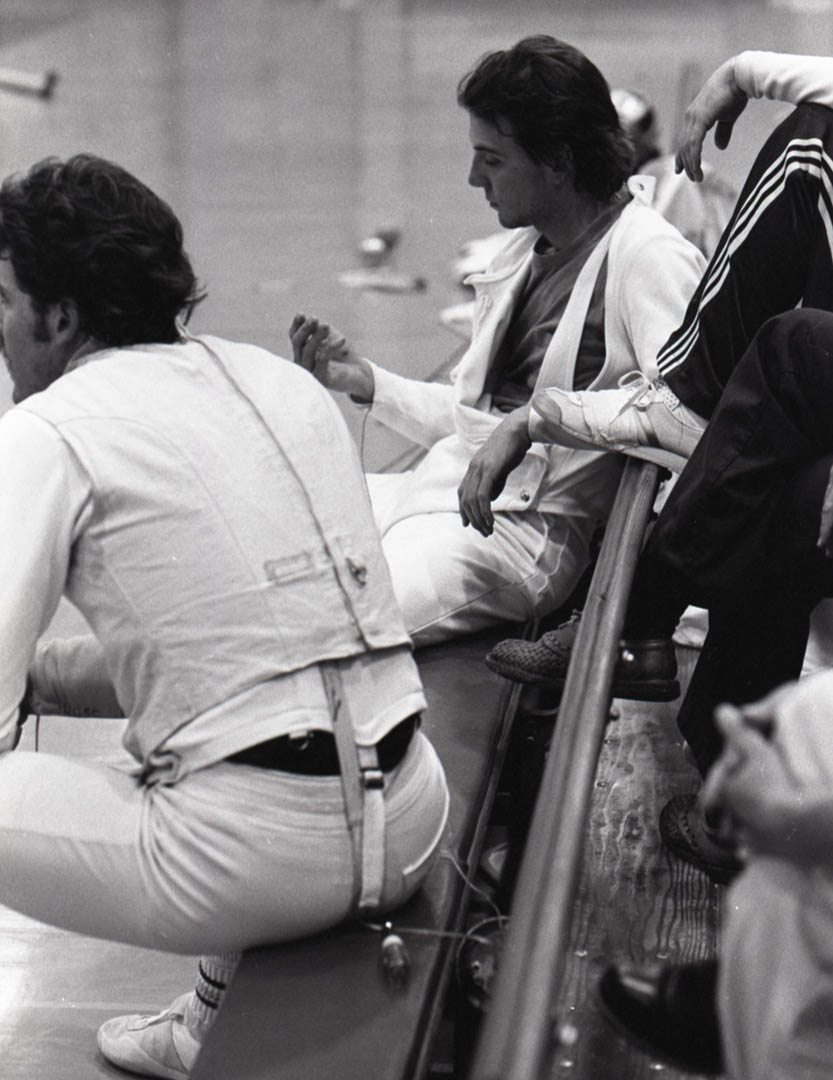

In addition to Kevin and myself, the other fencers who most dedicated themselves to learning from Len in those first couple of semesters were these three women: Claire Braunhut, Diane Russell and Debra Allen, with the proud coach tucked in between Diane and Debra.

At the end of our 4th semester of fencing, the Cabrillo women won the Northern California Junior College Women’s Team Championship. There were six or seven other schools but these three were unstoppable, taking, in order, 3rd, 2nd & 1st in the individual, as well. Kevin and I, along with our teammate Steve, didn’t fare quite as well. I think we took 3rd.

This article was from the Cabrillo school paper, the Cabrillo Log. The “bout official’ is none other than Ferenc Marki, whose San Francisco City College fencers had lost to the team from Cabrillo.

During my second year at Cabrillo, a new group of beginning fencers had begun to show real interest in the sport. Len had put a duplicate copy of the Junior World tape at the Resource Library that we could check out and watch in a little private booth. I often found, when going up to check it out in my free time (no telling how many times I watched that tape) it was sometimes already being watched by one of new fencers. That’s how I met John Ryan and Noel Hankla, soon to be fast friends and teammates. It became a habit that if the tape was being watched by an early bird, the second one in would just drop into the little booth and we’d watch together. At the end of my second year, Len decided we would have a Cabrillo intramural championship and stage the finals on a raised platform at an evening performance.

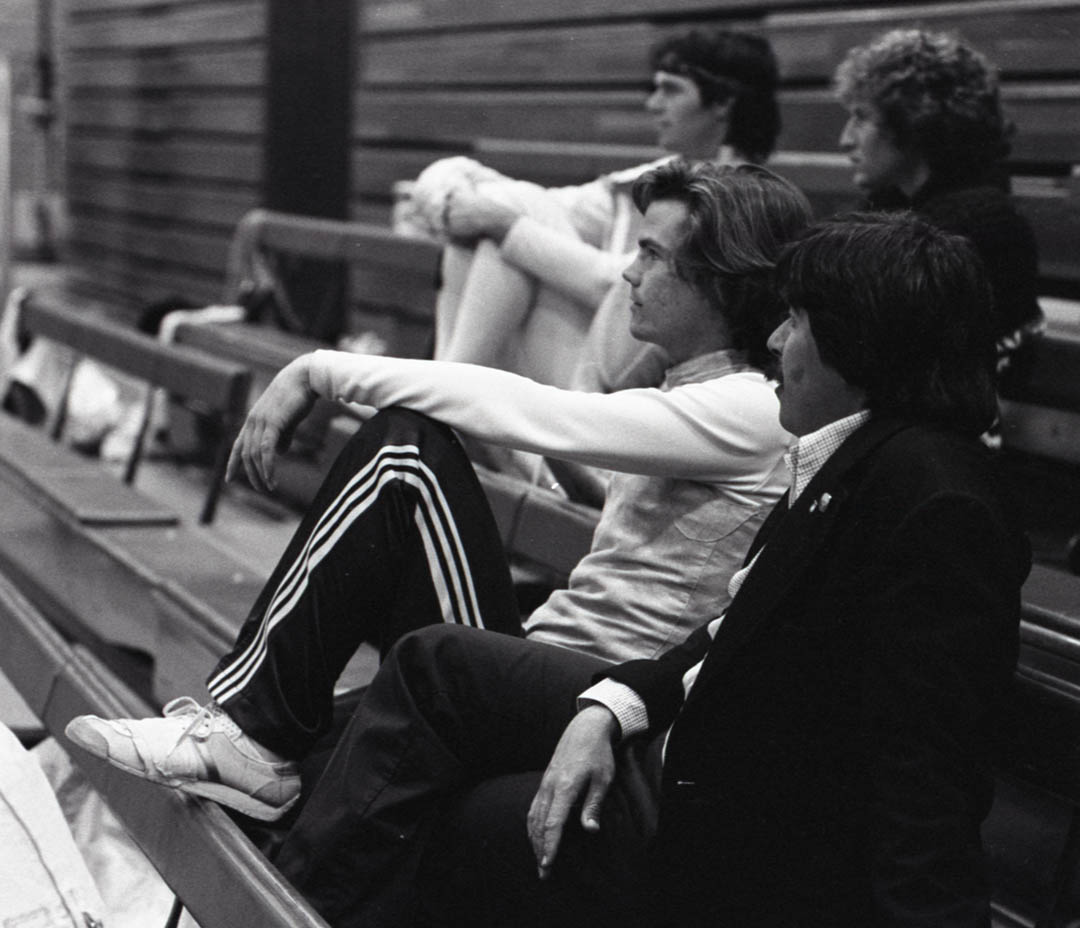

Kevin, on the left, helps me with warm ups for the finals as Charlie & Julie Selberg and Ted Pryor look on. Funny story about the platform. Len arranged to borrow the risers from Santa Cruz High School and sent Kevin and I over there to pick them up. We loaded them into the back of his ’72 El Camino. We drove down the hill from the school – we weren’t taking this load on the freeway – and crossed the railroad tracks for the Roaring Camp/Big Trees line that went from up in the redwoods down to the Beach Boardwalk. As we bumped across, we heard a “ssshunk!” sound. We both looked back to see that all the risers had slipped off the back and were right on the tracks. As we turned to look at one another in surprise, our looks turned to shock as we heard from up the street the “wheeeeeee!” of the steam whistle as the Roaring Camp Steam Train headed toward the Boardwalk. The only thing in their way was our stack of risers. We leapt out of the car, raced to the tracks and moved the risers – there were 10 or 12 of them, 4×8 1″ plywood boards with legs – faster than humanly possible. If we’d been filmed, we would have shown up as mere blurs. The whole time we were rushing to clear the track and reload the car, we both were laughing hysterically. I think we laughed the whole way back to Cabrillo.

The intramural was a hard-fought affair, as the evening finals event had been so hyped by Len in the classes that everyone wanted in on the action. I think about 40 fencers came out for the qualifying rounds and bouting continued until we were down to six for a round robin final pool.

The newcomers, Noel and John, both made the finals. They were roommates at the time, sharing a little house in Capitola. This is the final order, 6th to 1st from left to right: Kevin Kelsen, Diane Russell, Noel Hankla, John Ryan, Debra Allen, me, then Len and his son, Lencin Carnighan. Debra and I had each dropped a bout in the final. She’d beaten me 5-4, but lost to Noel. In the fence-off, I was able to win 5-4. Ever a tough bout between the two of us.

There was other excitement in the finals, too. Charlie Selberg had come down from UCSC to officiate the bouts. During the match between Noel and Kevin, Kevin’s blade broke, pierced Noel’s lamé, jacket and t-shirt, and ripped a not-deep, but bloody gash across Noel’s chest. While Noel was getting patched up, Charlie paced up and down in front of the audience of the 70-ish friends and family in attendance, and loudly assured them that it was, really, a very safe sport and that in his 25 years of fencing (at the time) he’d never, ever seen an accident like this. Noel, patched up and given a tetanus booster, got back on the strip and finished the bout, beating Kevin handily.

Noel Hankla grew up in San Bernardino, CA and was a star linebacker on his high school football team. His dream of going to college on a football scholarship evaporated after facing a player from another team, a running back who was the only player he ever met that was bigger and tougher than him, and near impossible to bring down. He described having foot prints up his front and down his back from this monster of a player. Playing against him made Noel realize that he would be overmatched at the next level if he would be competing against guys like that. That player’s name? Ronnie Lott.

Each of my teammates and training partners from those days at Cabrillo were unique, interesting and creative, each in their own way, and continue to hold a special place in my memory.

Diane Russell, wearing the Freedom Fencers patch – a California flag with “Freedom Fencers” embroidered under the bear’s feet – straightens a blade in preparation to hitting hard enough to bend it again. Although lacking in fencing experience – as we all were at the time – Diane was a mentally tough competitor and had some great finishes at big events. A competitive climber, she won the speed climbing competition at the very first X-Games and remains involved in that sport as co-owner of Santa Cruz’s Pacific Edge climbing club.

John Ryan and Kevin Kelsen at a Santa Cruz beach. As is happens, they were watching a fencing match when this photo was taken. These two, like me, ended up spending time at San Jose State to train with Michael D’Asaro, John first, then Kevin. John was part of my Western Regional-winning foil team in 1981. Kevin and I were roommates along with Spartan fencing teammates Joy Ellingson and Laurel Clark. That was a house to remember, believe me.

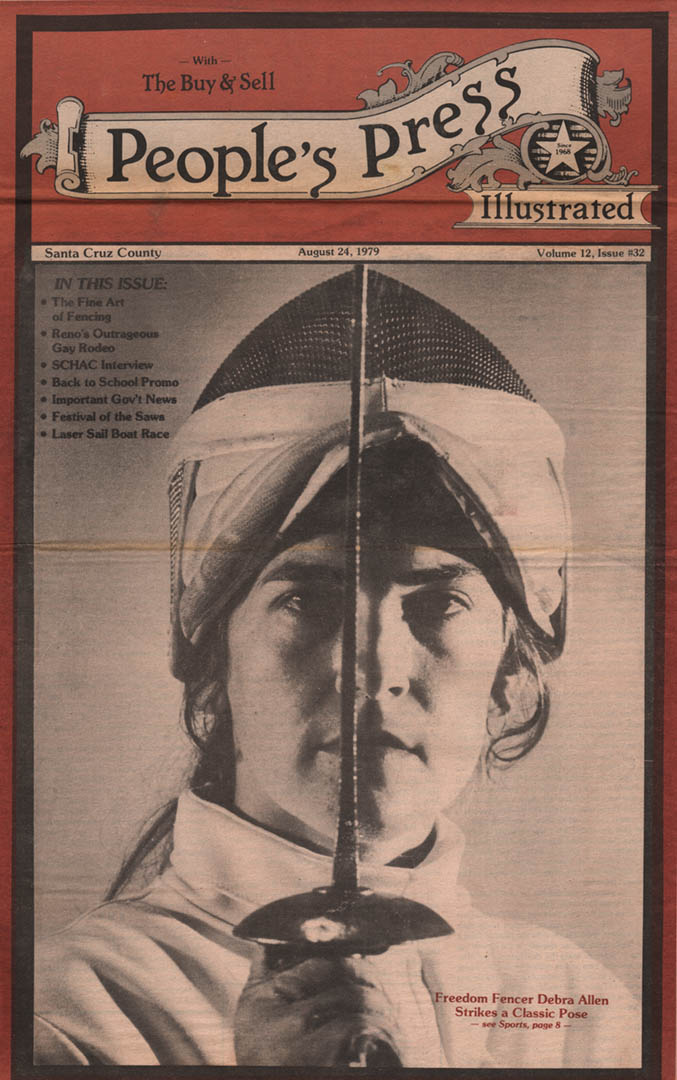

Leave it to Debra Allen to make the cover of the local paper. She fenced with classic form and was a tough competitor. On the local scene, she won a lot of tournaments. Only when the nationally ranked ladies from San Jose showed did she have to look at fencing for less than first place.

Claire Braunhut was like my twin sister. We were born less than a day apart and both loved this crazy fencing sport. She eventually got her little brother Ed into it, too. She lived up in the Santa Cruz mountains with her family and I often gave her a ride home after fencing at Freedom, about a 45 minute drive with a return drive back to my home in Aptos of a half hour. Still, you’d do anything for family, right? Claire stopped fencing a year or two after leaving Cabrillo, leaving a hole in my heart that was made permanent when I learned of her suicide in 2008, age 49 years. I miss her still.

When you live and fence near the beach, it only seems right that you and a few friends along with some swords and masks would make their way to the beach once in awhile. During my time at Cabrillo, we had a couple of very memorable beach tournaments with rather unique adaptations to the usual rules. The “strip” was basically the entire beach from sand to shore and into the water as deep as you cared to go. There wasn’t an end-line, so you could run as far as you liked and everyone acted as a judge, majority rules, no exceptions. We would draw names out of a hat for who fenced who and the first name drawn could pick the weapon, single elimination down to the last fencer standing.

Debra went with the classic look of a white skirt, but nowhere near as hazardous as the very short 80s sportswear we men were wearing. John Ryan, on the far left, to the surprise of no one, went without bothering to don a fencing jacket for his bouts, no doubt assuming he’d go through the day without being hit. He likely came close. I think he won that day. With John, Noel and I looking on, Debra is up against one of Len’s UCSC teammates, Jonathan Holtz.

Really though, you never quite knew what to expect. Len attempts to use a chair against Diane Russell. I suspect it didn’t do him any good.

But every now and then, a fencing bout would show up. This one is Jonathan Holtz and Noel Hankla.

In addition to the occasional beach tourney, our Santa Cruz contingent hit the road for all the Central Cal and Nor Cal tournaments and often drove down to Los Angeles to brace the SoCal contingent. This photo was taken late in the day at LA Valley College, a frequent venue for LA division tournaments at that time. John, far left, clearly eliminated, is starting in on the beer supply. Then Marc Walch, Kevin and Noel. If my memory serves, this was at the Mori open. I’m pretty sure Noel beat Marc which put him in the final match of the day where he got a chance to fence Heizaburo Okawa for first place. Noel got in some touches, but that match finished out the way you’d expect. The biggest treat was, since Okawa was there to put on a show as much as win the tournament, he hit Noel with his patented touch where he twists, drops and turns to face you upside down – the move immortalized in the famous poster. Not once. Twice.

By 1982, our Santa Cruz group was running the Central California division. Len, rightly, strategized that if we ran the division in a ‘Santa Cruz’ fashion, some new blood from San Jose would eventually get frustrated and take back the running of the division with new energy and focus. (‘Santa Cruz’ fashion meant hold the tournament in Santa Cruz with a noon start time.) He was right, but it took 2 years and coincided with the opening of The Fencing Center in San Jose. Noel and I ran the 1982 Pacific Coast Championships and did a decent job, but there wasn’t enough room to hold team events. This was us near the end of the event. Exhausted, we both went out in the early rounds.

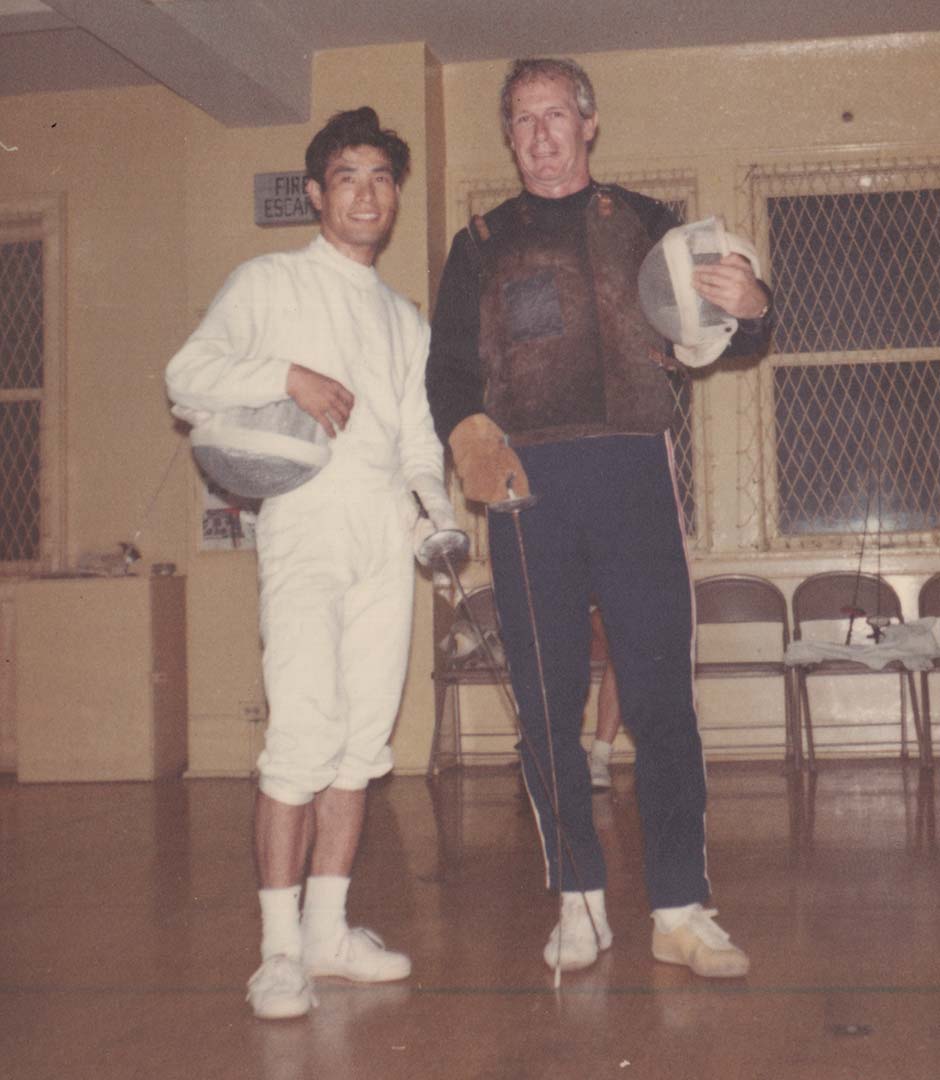

I’ll end with this one. Me and Len, taken at the First Annual Buchwald Open, sponsored by Alan Buchwald, and held at Cabrillo College in 1982. The summer of 1982 was a watershed moment. Len was one of the finalist in consideration for the job of taking over the UC Santa Cruz fencing gig when Charlie Selberg retired, but lost out to Delmar Calvert. He decided to leave town, left the job at Cabrillo and moved to Ashland, Oregon. Charlie, too, moved to the woods outside Ashland and John McDougall followed not long after. In 1985, after leaving San Jose State, Michael D’Asaro and then wife Gay also moved to the Ashland area. That’s a lot of fencing coach talent in one place. Len is another of the folks on this list that I miss dreadfully. As I write this on September 1st, we’re just ten days away from marking the 3rd year since Len committed suicide. He was another veteran who, as a teen, had PTSD imprinted for life onto his DNA during his time in Viet Nam. That sad end doesn’t resign him to a mere statistic about military suicides. His memory is too vivid, his influence as teacher, mentor and friend too current. And those memories are intertwined with those Santa Cruz-centric summer days spent with special friends whose essence and presence remain unchanged as I reflect back on the times we spent. Fortunately, these aren’t maudlin remembrances. The admirable qualities of the individuals and the combined energy of this group was all too grand in the moment to reflect upon it with anything other than joy in the memory.

Yet More Comics!

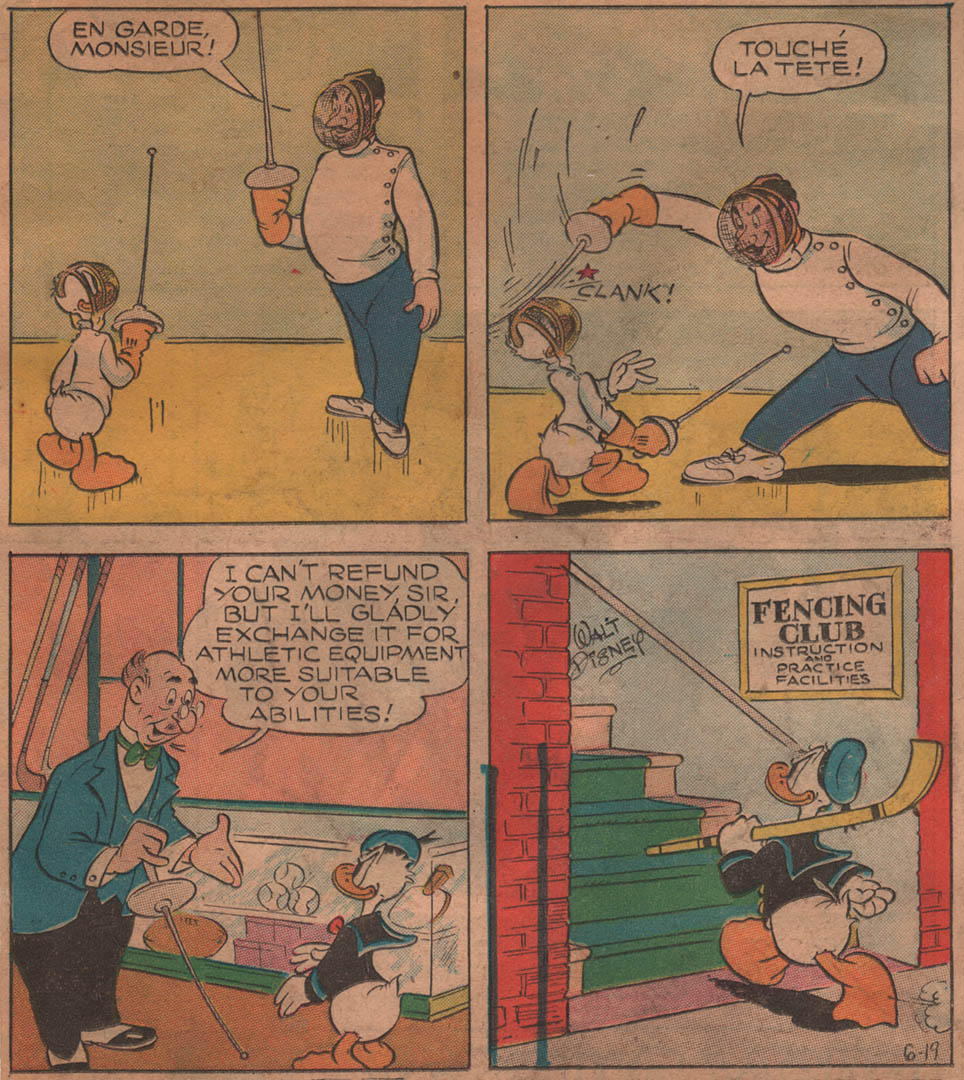

If you have ever taken the time to peruse the backlog of stories on this site, you may have run across a few older posts that had collections of newspaper comics that include a fencing reference. Well, it’s that time again! And if you haven’t checked out the older ones, feel free to do so if you enjoy today’s offering. Just search for “comics” with the magnifying glass icon and you’ll find a bunch more.

As with the earlier posts, these all come from the Halberstadt Scrapbooks. Hans collected newspaper clippings, magazine articles, advertisements, comics like these – basically anything that some hint of a fencing component. In his scrapbook, they tumble from year to year in no order other than what an empty page and some handy glue or tape made possible as things came his way. I wish I could have seen the original books before floodwaters forced an heroic re-mounting effort by Halberstadt club members. Ah, well.

Forward, into the past! Today’s offerings are all from the earliest of Hans’ scrapbooks, and date from 1949 to 1951.

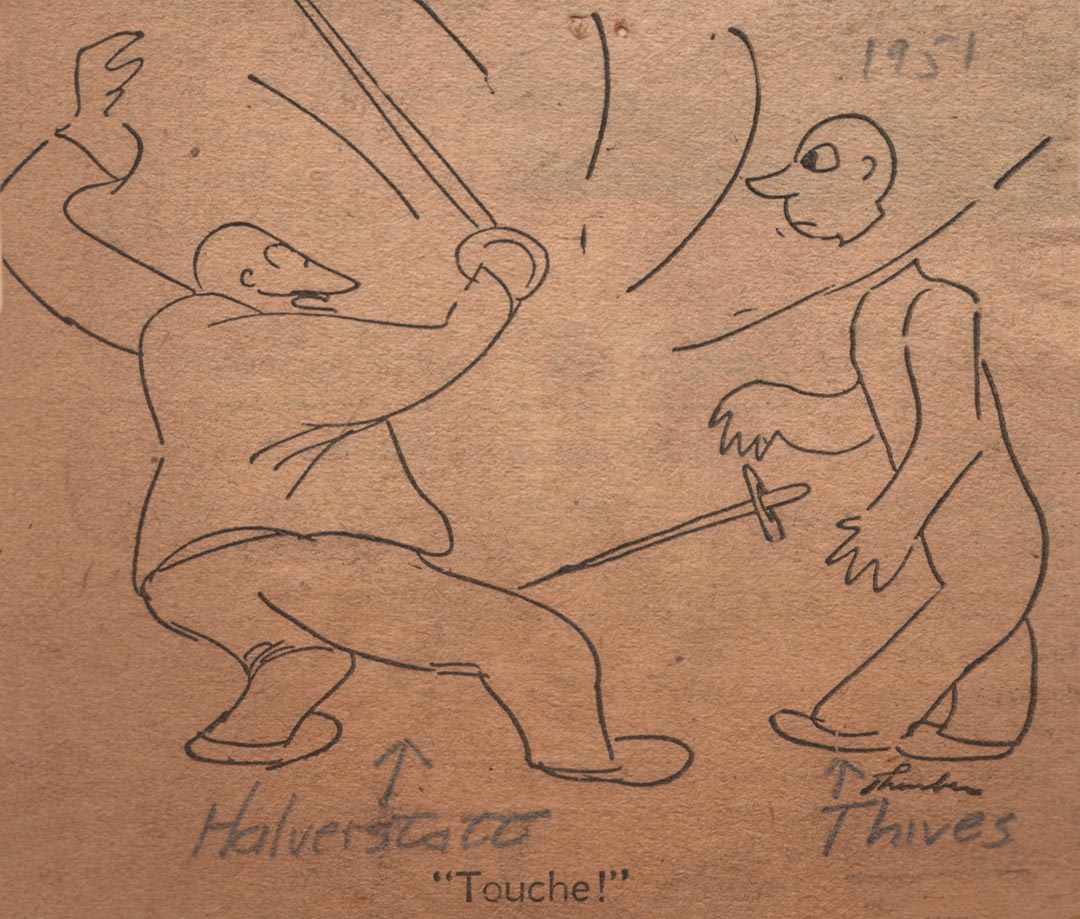

This James Thurber comic must have come to Hans as a gift. At a guess, I’d say from a Mr. Thives who, apparently, struggled with the spelling of Hans’ last name. Halverstadt, indeed.

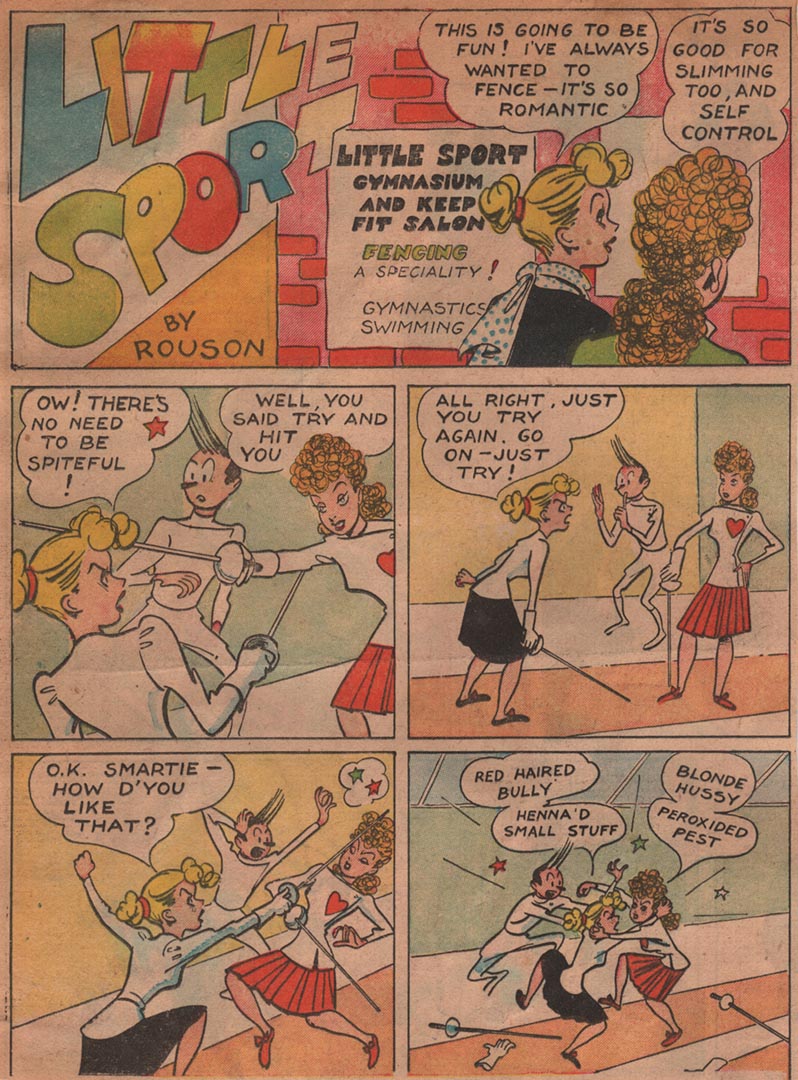

In 1950, when this was published, skirts were still to be seen, albeit infrequently, in some ladies fencing circles. Within a few years, they were gone for good. As for the balance of this comic and the poor example of behavior exhibited by “Little Sport” (I’m guessing the blonde) and her friend, I can’t see officials today tolerating this sort of behavior. Or at least, not very often.

Just like on the internets, CAPITALIZING YOUR LETTERS DENOTES SHOUTING, even in 1950.

No caption for this one. Does it need one?

This one doesn’t.

Perhaps one day I’ll tell the tale of what may have happened in the parking lot of the now long-gone Positively Front Street pub in Santa Cruz, CA after a night of imbibing when a challenge was thrown down. All I can say is that Michael D’Asaro Jr. was witness to the event and he called it “the craziest thing I’ve ever seen in fencing”. Today is not that day.

Finally, two with Donald Duck.

That’s all for today! Bring on the week!

The Search for Al Snyder, National Champion

Typically, US National Foil Champions are reasonably well documented, particularly in their home town. That doesn’t seem to be the case with Alfred R. Snyder, 1944 US foil champion.

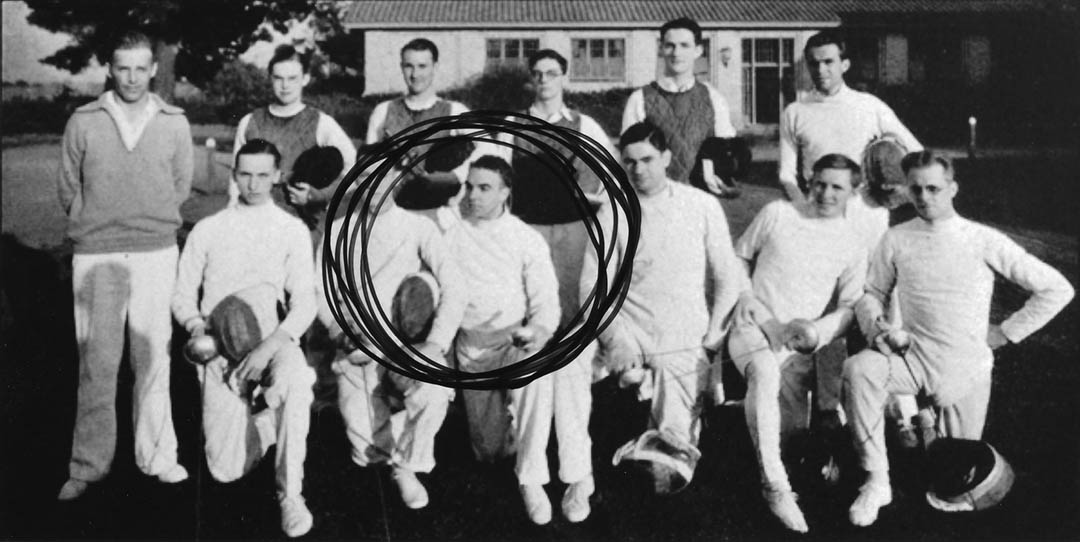

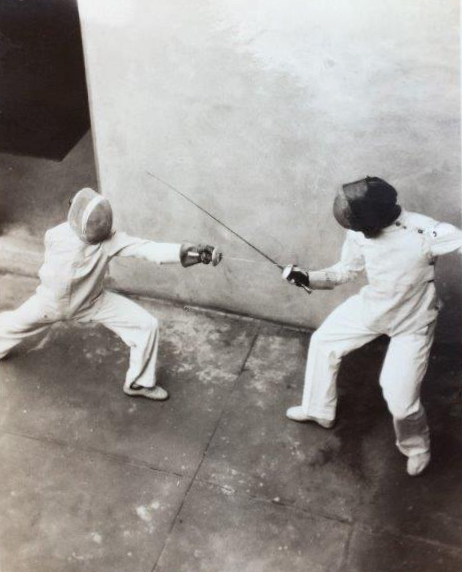

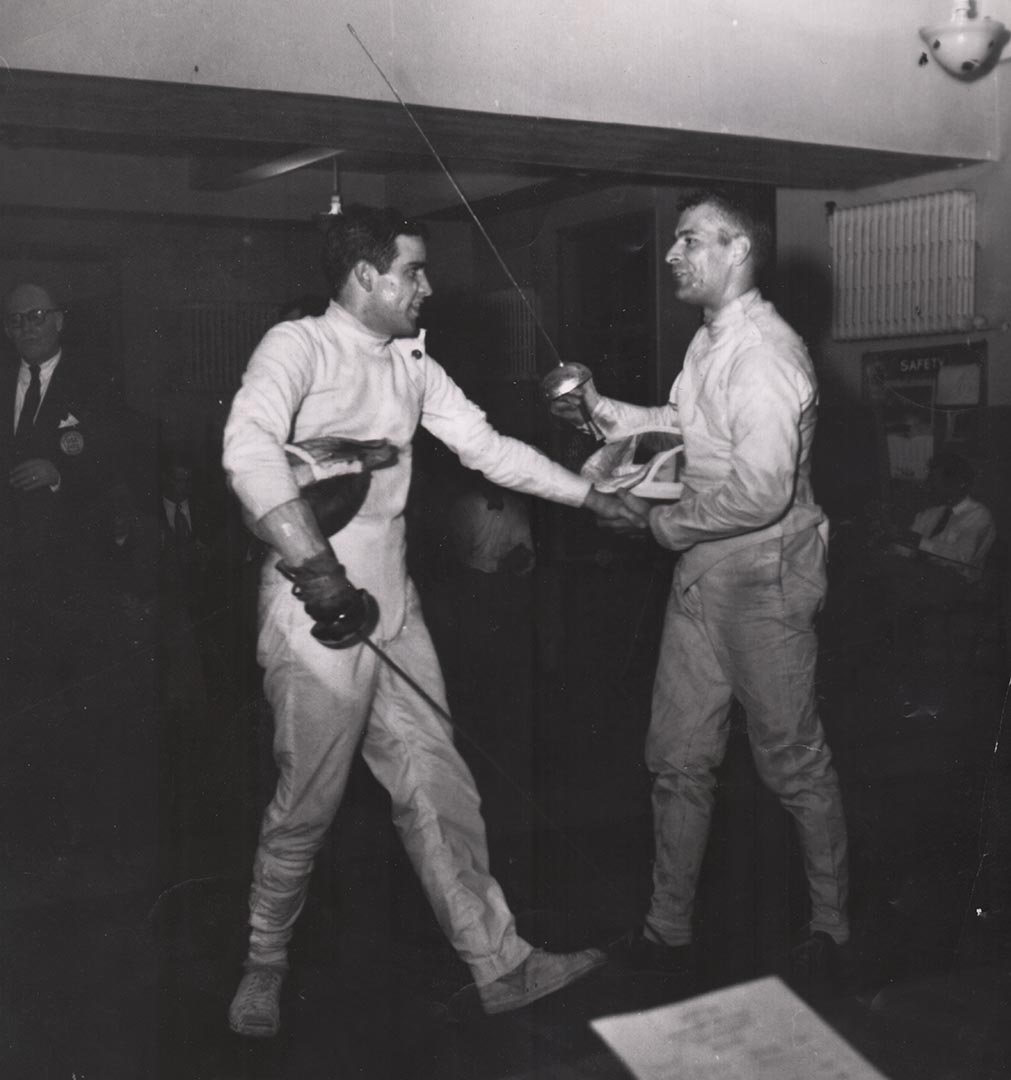

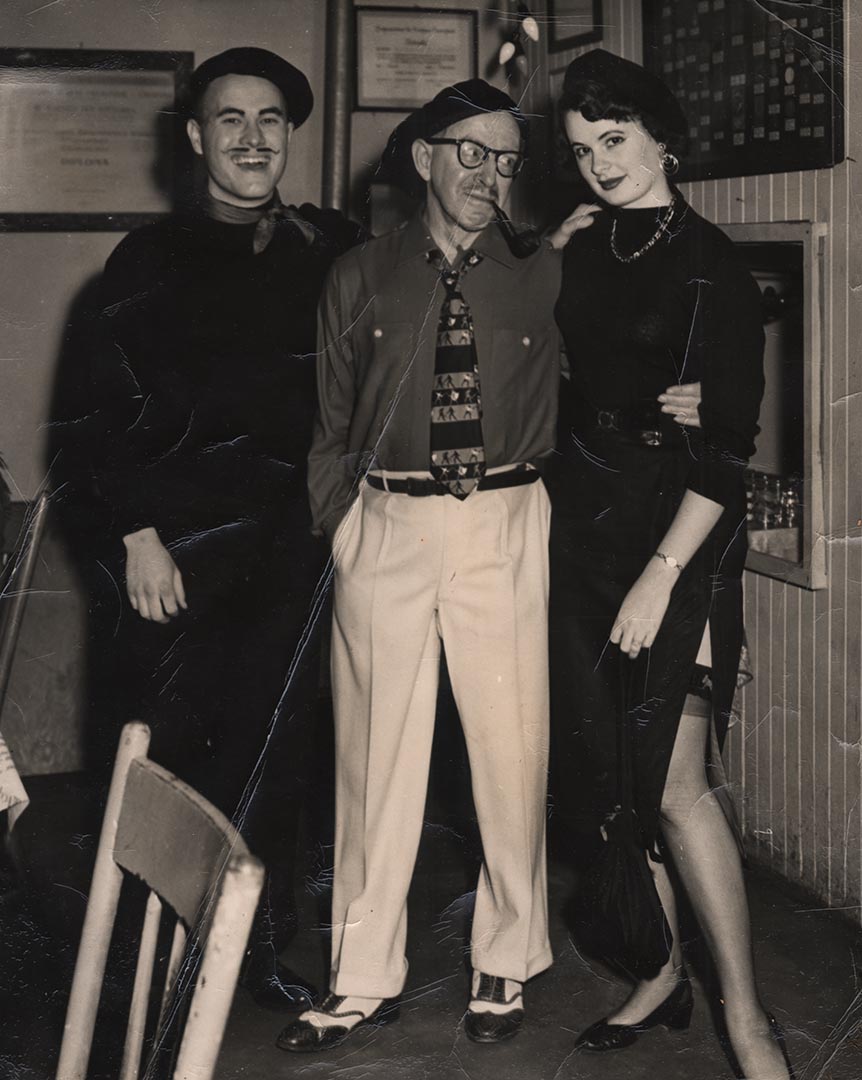

Andy Shaw, the USA Fencing Historian and owner/proprietor/chief dog rescuer at the Museum of American Fencing, gave me the name Al Snyder some months back to see if I could dig up any cache of information, since Al’s fencing career began and ended (apparently) in the San Francisco Bay region. For good or ill, my thoughts about fencing history hone frighteningly close to Andy’s, as I had, not a week before, found the first and still best photo of Al Snyder in my collection and it’s a pretty unforgettable image. It’s the one at the top of the article, with Snyder on the left. What do you notice first? That Al Snyder was left handed?

Al Snyder, winner of the National foil title in 1944 and silver medalist in both 1943 and 1945, would have been on the US Olympic men’s foil team, if not for the lack of Olympics during the war years. I’m not sure that he would have been the first one-armed Olympian to compete in a sport at the Olympic Games but how many can there have been? If the timing of the world were different and he’d competed in the Olympic Games with only one arm, win, lose or draw, I’m guessing he would have become a household name for those giving any thought to humans overcoming physical challenges.

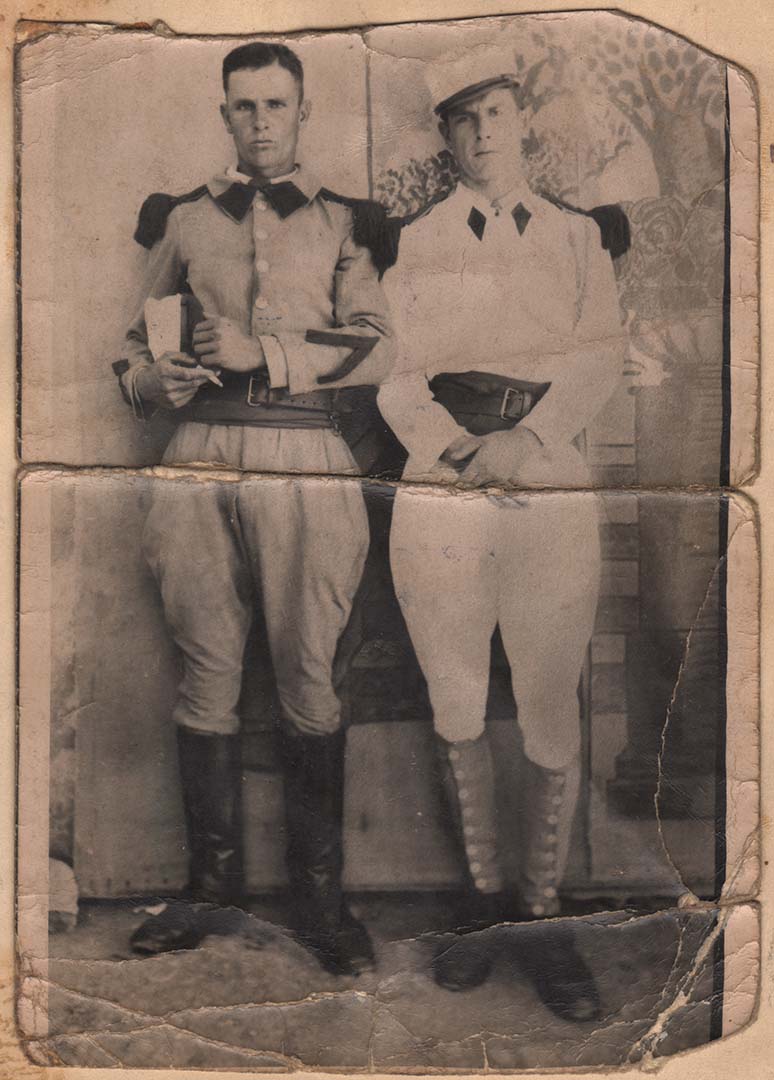

The first record of him as a fencer comes from Stanford University annuals. (This gets convoluted, so please bear with me.) He shows up in the Men’s Team photo in every edition of the Stanford Quad that I’ve seen, 1932 to 1937. By 1937 he was no longer on the team but the photo lists him as a graduate student and Pacific Coast Champion. His coach, possibly coaches, would have been Harry Maloney and/or Elwyn Bugge. Bugge was Maloney’s assistant in both tennis and fencing from 1928 on, a position he took up after his own Stanford graduation. One document in the Archive collection, a compilation of fencing coaches at various Bay Area clubs that was put together by Maestro Arthur Lane around 1955, indicates Bugge as the Stanford coach from 1927 and I’m guessing he started assisting while still a student. (The Stanford Quad lists him as starting in ’28. Lane’s source for the ’27 date was Elwyn Bugge, so I’m guessing the earlier date is correct.) Bugge remained the Stanford coach as late as 1957 and also coached for some years at the Olympic Club in San Francisco.

The 1934 photo from the Stanford Quad. In most of the photos from his Stanford years, Al Snyder made sure to line up with his right shoulder behind one of the other fencers, thus minimizing the chance for a casual observer to note his lack of a right arm.

Interestingly – and Andy Shaw and I have been going back and forth about this while I write my article – the earliest appearance of what seems to be Al Snyder at Stanford is actually 1929. I’m keeping in the previous paragraph with the dates as I wrote it, since that’s how I understood things when I began this piece. I had decided the guy listed as Snyder couldn’t be the same guy as the National Champion. His hairline was too different and he had a totally different face shape. (The available photos have lousy resolution, so it’s a tough read.) In the interim, Andy convinced me that the 1929-30 Snyder is the same guy as the later one. With one difference. He has two arms. In my original run-through of Stanford annuals, I couldn’t find a picture of the fencers from 1931. Just now, in going back through the 1931 annual one page at a time (thank you, e-yearbook!), I’ve come up with one. My problems with the 1929-30 Snyder are, I think, justified. On this new-to-me page, from 1931, there is another Snyder and this one not only has the right hairline, but he’s listed as a Freshman. I think this is him for sure. And with all of that, the 1931 Snyder also has a right arm and is holding a foil with it. In 1932, he only has his left arm and he’s switched over, perforce. So, and I’m pretty certain after all that, sometime between 1931 and 1932, Alfred R. Snyder, rising sophomore at Stanford University and future National Champion, lost his right arm.*

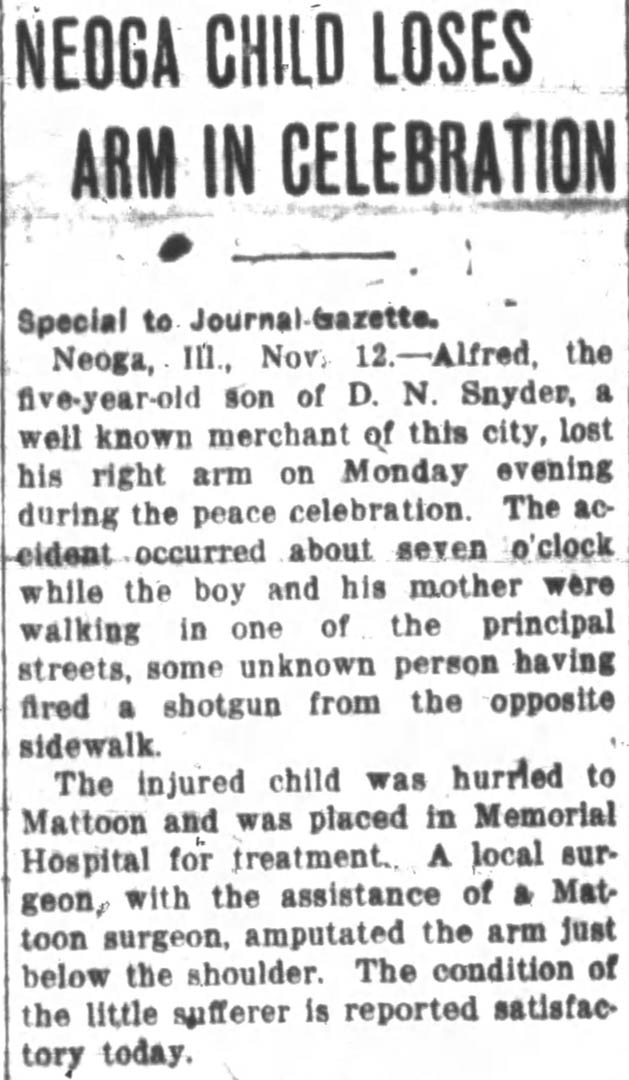

*I was wrong about the timing of the loss of his arm. Reader Mike Perka found an article from 1918 that seems to indicate that Snyder lost his right arm at the age of 5 during the celebration of the end of WW1. And I completely mis-interpreted the photo from the 1931 Stanford annual. I looked again more closely. Al’s left handed and hiding his right shoulder behind the fencer next to him. Here’s the article Mike found:

Ok, back to the story!

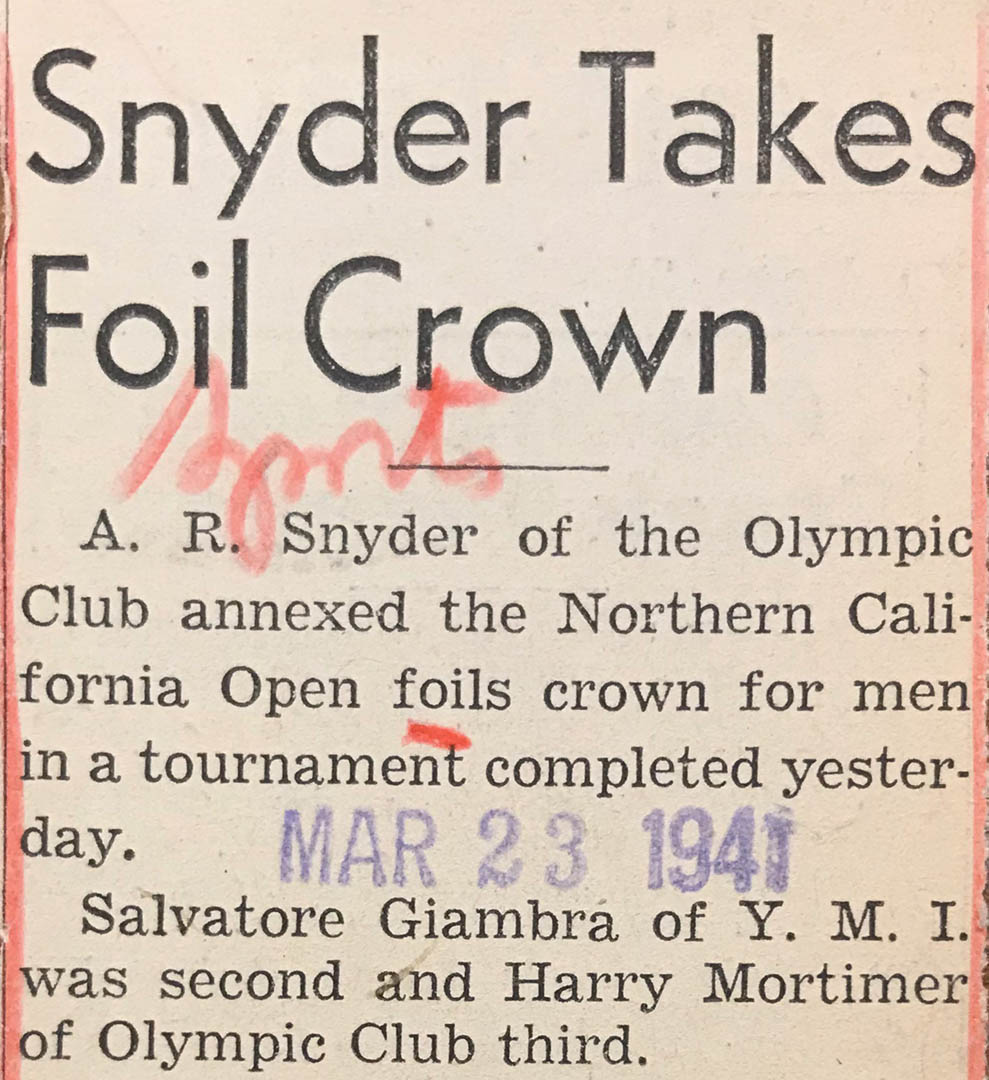

There are quite a number of articles in the Archive from various newspapers across multiple sources that mention Snyder’s name and accomplishments. From about 1937 on, he won just about every local competition he entered. And it is frequently noted that he had no defeats. There’s one where he did have a defeat or two but he’s in good company.

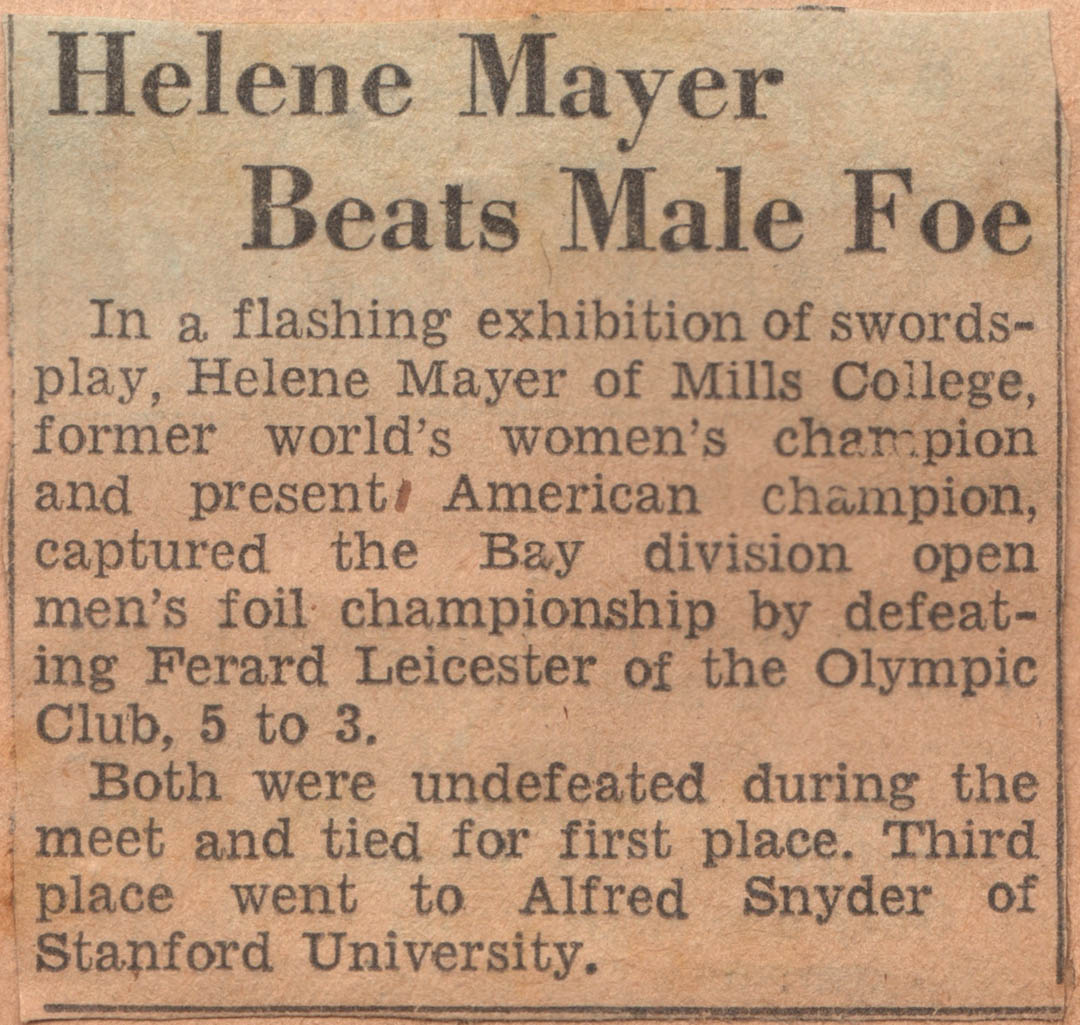

Al Snyder comes in for a bronze medal at a Nor Cal Open, finishing behind Olympic Club teammate Ferard Leicester and…. Helene Mayer! This event was the one that put Helene on the path to qualify to fence in the Men’s National Foil Championship. Unfortunately, the powers-that-be wouldn’t allow her to compete at the Pacific Coast Championships in the Men’s Open division since, had she won, she’d have been, by rule, qualified to fence at Nationals.

Snyder attended his first National Championship, as far as I can determine, in 1939. It’s possible he attended earlier ones but there are no extant records of the complete entries that I know of from this era. If copies of The Riposte magazine could be found, that would probably have them but the collection of issues to which I have access gets spotty prior to 1939. Snyder would have been qualified for Nationals in 1937 due to his winning the Pacific Coast Championships. In fact, he won two foil events at the ’37 PCCs. Because he was a relative newcomer, he participated in both the Intermediate and Open classification foil events, winning both.

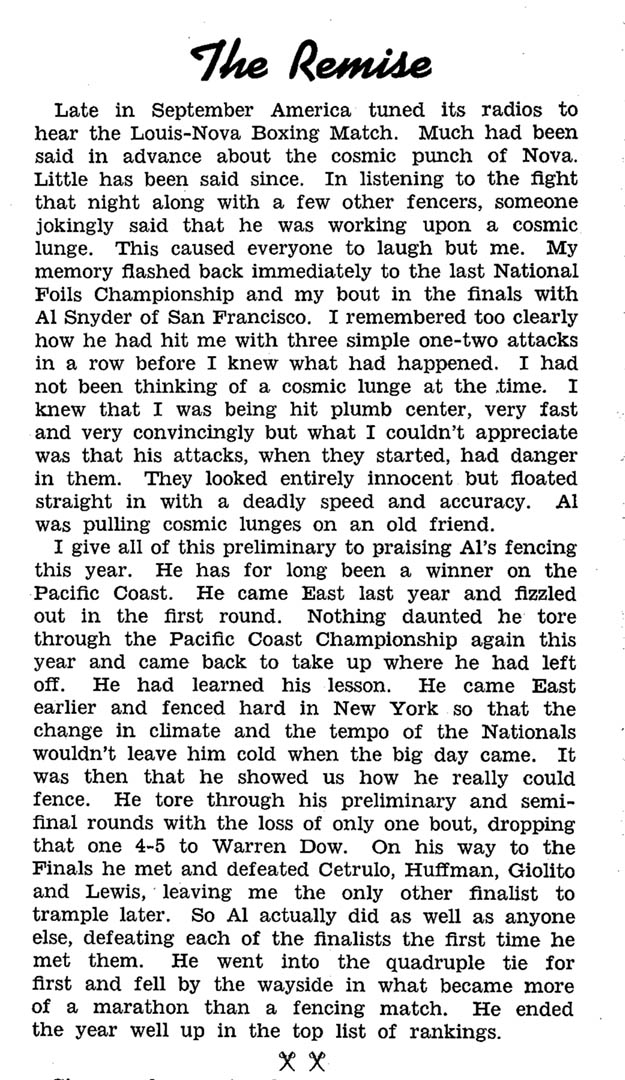

By the time 1940 came around, Snyder was a well-known and respected opponent, if I can base that claim on the following excerpt from The Riposte magazine and the reporting from Nationals written by Dernell Every.

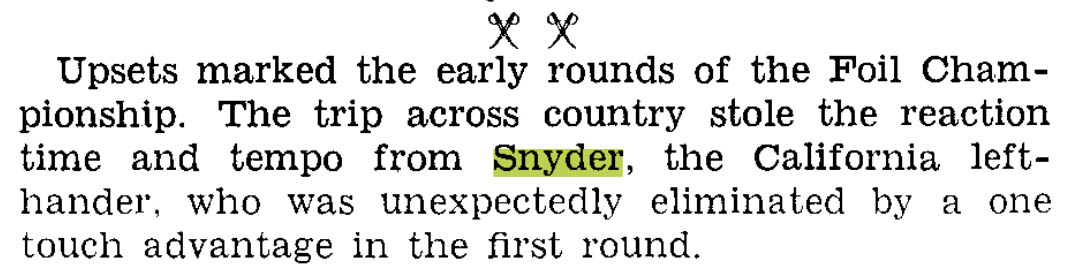

The previous year, 1939, Snyder was eliminated in the semi-finals, so this early exit in 1940 was a surprise.

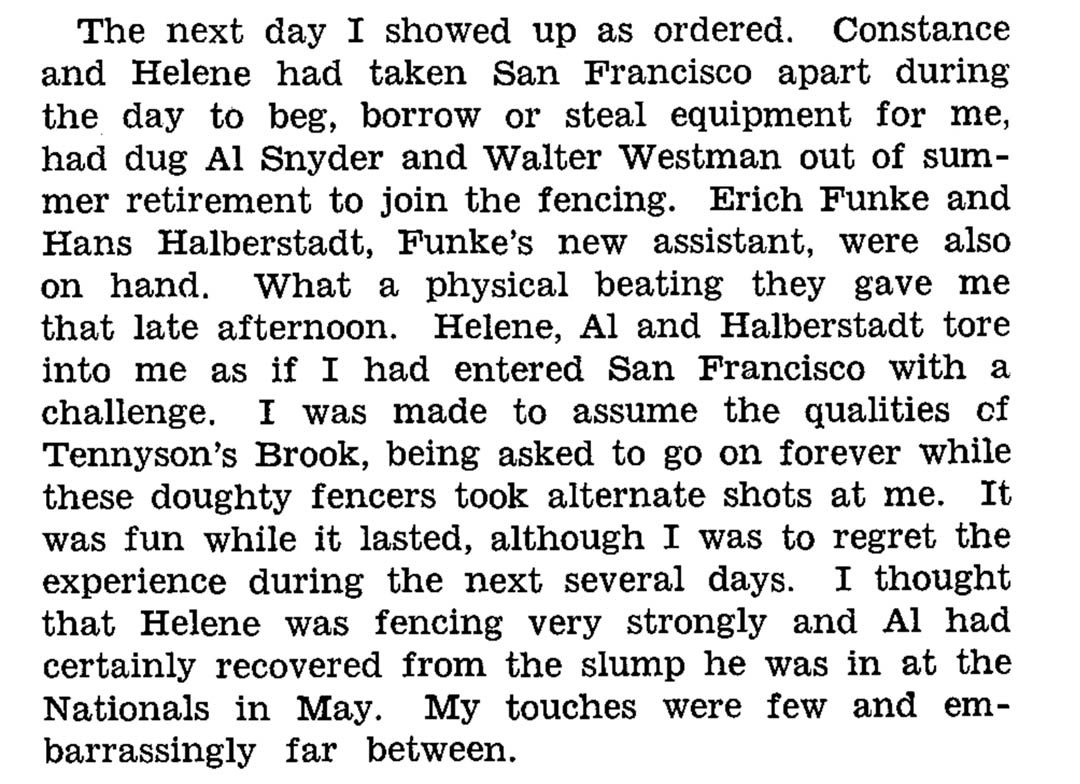

Speaking of Dernell Every, the editor of The Riposte magazine, long-time New York fencer, National Champion and Olympic medalist (Bronze, Team Foil, 1932), in the October, 1940 issue of the magazine wrote about a cross-country-by-train trip that he took with stops in a number of cities where the local fencers came out to give him welcome. Here is the description of his stop in San Francisco.

“Recover” Al certainly did for the Nationals in 1941. It seems he made the trip to New York for Nationals a little earlier than his previous attempt, giving himself time to acclimate and fence locally for a little while before the competition. Sadly, in the fence off he was low man, ending the day in fourth place and out of the medals. And, as was decided shortly after, out of automatic qualification for the following year’s Nationals. Even though he’d finished the day in a tie for first, the powers decided to give AQ status for Nationals only to medalists. No matter. Al won a bunch of PCCs and took several second place spots behind his long-time SoCal rival, Edward Carfagno.

Dernell Every had one more interesting write up about Al Snyder in regards to a thrashing Al gave him during the 1941 foil Nationals:

Joe Louis fought Lou Nova on September 29, 1941. Louis successfully defended his heavyweight title, his 19th defense, earning a TKO over Lou “Cosmic Punch” Nova in the 6th round. Nova turned actor after his fight career ended. Born in Los Angeles in 1913, Nova was a vegetarian and practitioner of hatha yoga, which he learned from Pierre Bernard, a pioneering American yogi.

In the past week, I’ve spent a few hours at the San Francisco Public Library’s Main Branch on the sixth floor in Special Collections, attempting to see if there was more information available about Al Snyder, his life, work, whereabouts, anything. Since he was a longtime member of, and competitor for, the Olympic Club in SF, I first went through the library’s collection of “The Olympian” magazine, published by and for the Olympic Club. They don’t have anything like a complete run, but they had quite a few issues. About every other issue from the 1930s through the 1950s had a write-up about the goings-on in the fencing room. The only mention of Snyder came in the description of the results of two Olympic Club foil teams at the US Nationals in 1939 which were held on Treasure Island in San Francisco Bay. Snyder’s team took fourth. The other team, the team that bombed out in the first round, got their picture in the magazine. Wait, seriously? Aaargh! Why not a picture of Snyder’s team?

Yesterday I went back to the library and went through the file of clippings about fencing from the San Francisco Examiner newspaper. And they were clippings, actual cut-from-the-paper clippings regarding fencing in two envelops. I thought surely there will be some terrific write-ups about Snyder from the war years describing his triumph at the US Nationals. In the three year run from ’43-’45 when he was second, first and second, there had to be some great stuff about all that. Feel good stories for the sports page, right?

Wrong. From about 1935 to 1941, there’s between 8 and 10 articles per year. Suddenly, in 1942, there’s two. None for the next couple of years. Then one. Then in 1946, it starts up again with multiples per year. So zero, zip, nada, about Al Snyder’s triumphs. Maybe there was only war news during those years. There at least seems to have been nothing about fencing. But, thanks to Andy Shaw, I have this:

Alfred Rex Snyder, holding the US National Men’s Individual Foil trophy in 1944.

Another casualty of the war years was a National magazine for fencing. The Riposte went dark in 1942 and American Fencing didn’t start up until 1949. In between there were some regional attempts, such as The California Fencer (later, just The Fencer) magazine, but they were short-lived. If there are Secretary Newsletters or something similar that spelled out the action during these years, I don’t have any.

After his three year run at Nationals that netted two silvers and a gold, Al seems to drop out for awhile. He doesn’t show in the top three places of the PCCs foil for several years, then suddenly pops up once again in 1949, taking first place. He attended Nationals that year, as well. That’s the last notice I have for him. The SF Library, in addition to pulling all the Sports/Fencing articles for me, also pulled an envelope labeled “Snyder, A-Z”, the idea being anyone named Snyder who got their name in the paper, that’s where their clippings would go. There were half a dozen. George, Robert, Phil, I don’t remember, just no Al or Alfred. Complete strike out.

One other article did mention his name, however. That was the obituary notice from 1966 for Hans Halberstadt. It reads, “After his release from Buchenwald, Mr. Halberstadt came to this country and developed many fencing champions, among them Al Snyder of the Olympic Club, 1941 foil champion of the U.S.” They got the date of his championship wrong but it’s a handy piece of information to know that Snyder may well have been under the tutelage of Hans Halberstadt. Hans was an instructor at the Olympic Club for quite some time in addition to his work at his namesake club, so it makes sense that Al would have availed himself of the free-to-members lessons from the only Bay Area coach at that time with international competitive experience.

Another photo courtesy of Andy Shaw.

I’d love to know more about Alfred Rex Snyder. But where to go? I know he was a grad student at Stanford; maybe they’ll have something. I need to check, certainly. Gerard Biagini, who I spoke with recently, thought he was an engineer of some sort. (They weren’t close in age, so even though they were teammates at Nationals in 1949, they weren’t close personally.) He also thought Al was married. If Snyder had been on an Olympic team in 1940 or 1944, there would be a Wikipedia entry that would at least give me his birthday. I don’t have even that. Everywhere I look to find something other than fencing records, I strike out. Maybe getting his name out on the interwebs will spark someone’s memory that will lead to more information coming my way. Here’s hoping.

Living By The Sword

During an otherwise very pleasant Italian meal I shared with two-time, two-weapon National Champion and Olympian Sewall “Skip” Shurtz and Andy Shaw of the Museum of American Fencing, Andy mentioned that he’d come to appreciate, late in life, a difficult-to-like fencer who was once a teammate of Skip’s. Grabbing the nearest-to-hand weapon, a butter knife, Skip aimed it in Andy’s direction, saying, “Don’t you dare say anything good about that son of a bitch!” Only a little butter and no blood was spilled but it gave me pause to wonder just how tough Skip Shurtz had been prior to a massive heart attack that had slowed him considerably. I only met Skip after that heart attack, and so never experienced the full blast of his energy and passion. Knowing he learned how to drink and fight in the Navy and was a fearless competitor, completely willing to go toe-to-toe with anyone – anywhere, anytime – I can only imagine how this scene may have played in earlier years. I don’t pretend I would have fared well as an intermediary.

For some time I’ve had plans to put together a book about Skip’s life and he and I worked together on gathering his stories into some kind of shape prior to his passing away in February of 2018. Skip’s memory stayed sharp through our discussions and I was able to get him to answer some of my questions in writing. However, his answers tended to lead to more questions. There’s many a mystery that I’ll never solve now but I still feel like I was able to stitch together a pretty fair picture of the man. Time to share some Skip memories.

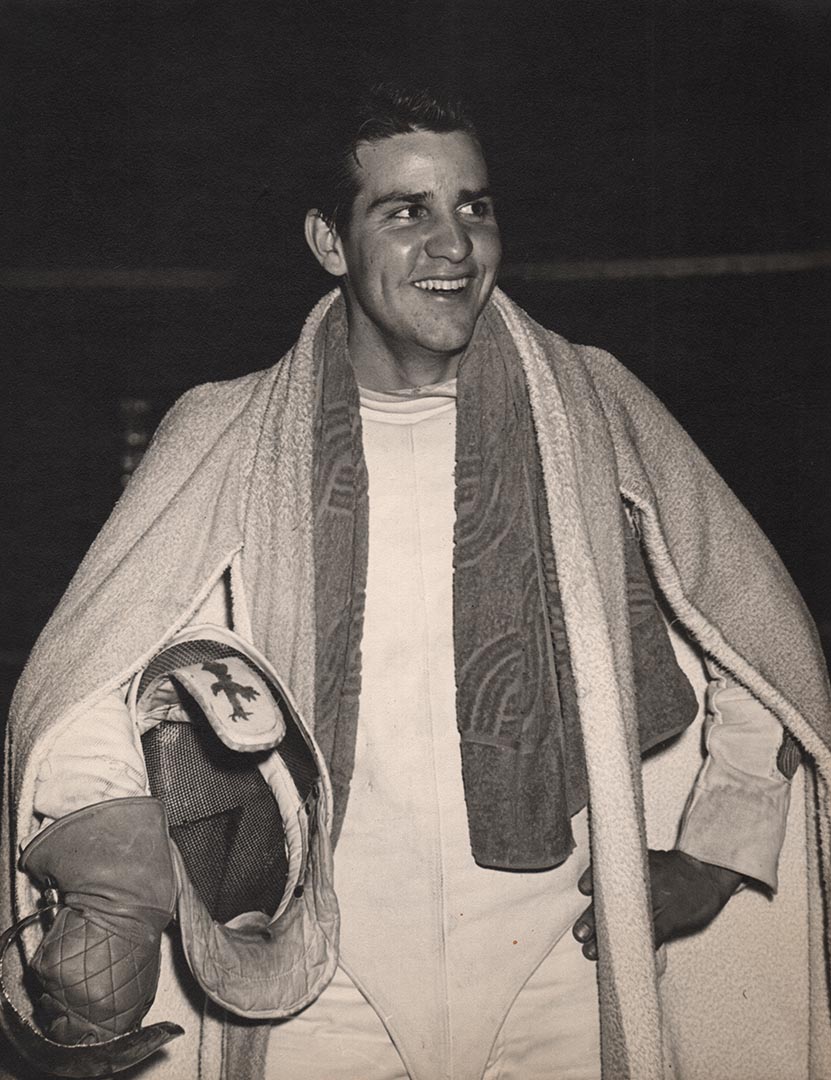

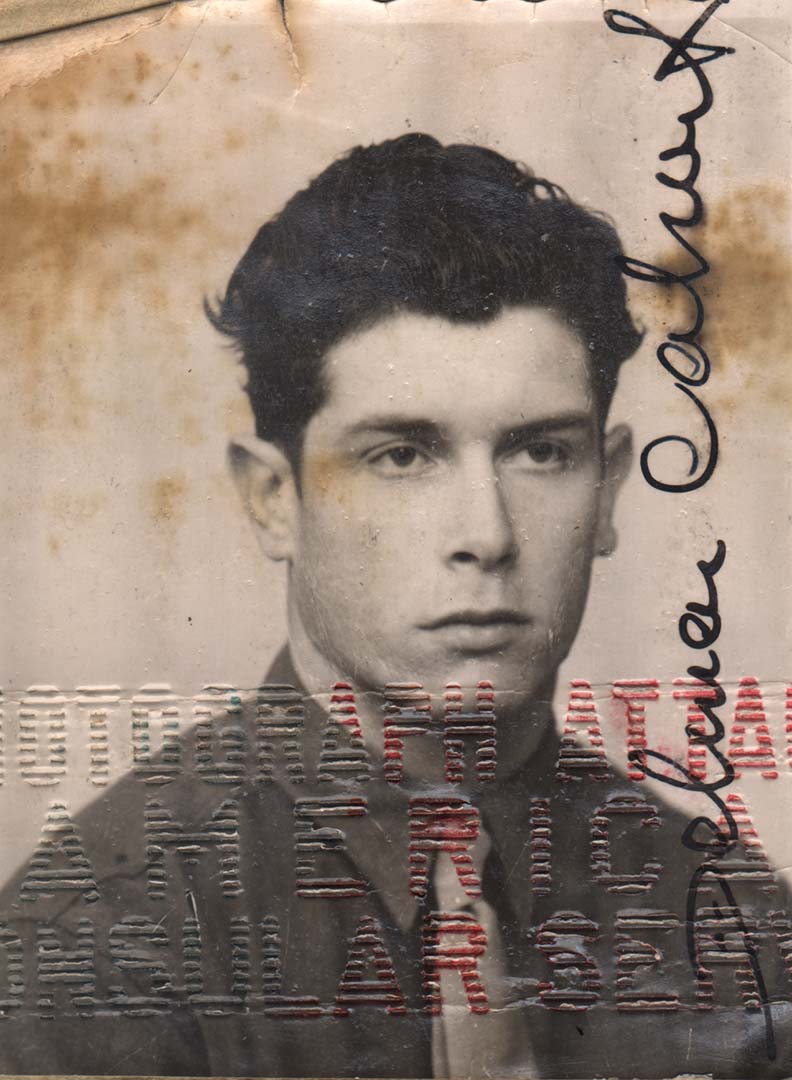

Skip at age 6, ready to take on the world.

Sewall Shurtz was born in the Texas of 1933 to a woman in an unhappy marriage who, when Skip was still very young, packed up her son and her mother and escaped to the Golden West and the city where dreams are made: Hollywood. From an early age, young Sewall was put through dance classes, acting classes, fencing classes – anything to prepare him for the grind of pursuing the pinnacle of success: Movie Stardom. Skip, along with a smallish group of other silver screen hopefuls, was shuttled from casting office to casting office, hoping for THE part, or any part, like soundstage vagabonds. Both his mother and grandmother worked any possible job to keep them in food. They lived on the Hollywood fringe, always poor, but somehow surviving, pouring what extra money was available into the classes and situations that would give Sewall that chance at success in the film industry. Skip suffered from rickets, a common enough condition in children from struggling families, but was never allowed time to imagine that anything could stop him working if there was a part to be played.

The boy in the front, with his pals at Universal Studios before the theme park.

The life of a young actor in Hollywood in Skip’s era was a constant cycle of rehearsals, auditions and performances. The many local dance and acting schools would put up show after show, anything to create exposure for their students. In between, the parents of young children would work with agents to find out the casting opportunities and make sure their protégés were polished up and ready to go on cue. Skip and his peers slipped from one costume to the next, all the while learning lines and prepping for the next round of auditions.

Skip shows the girls how to lunge.

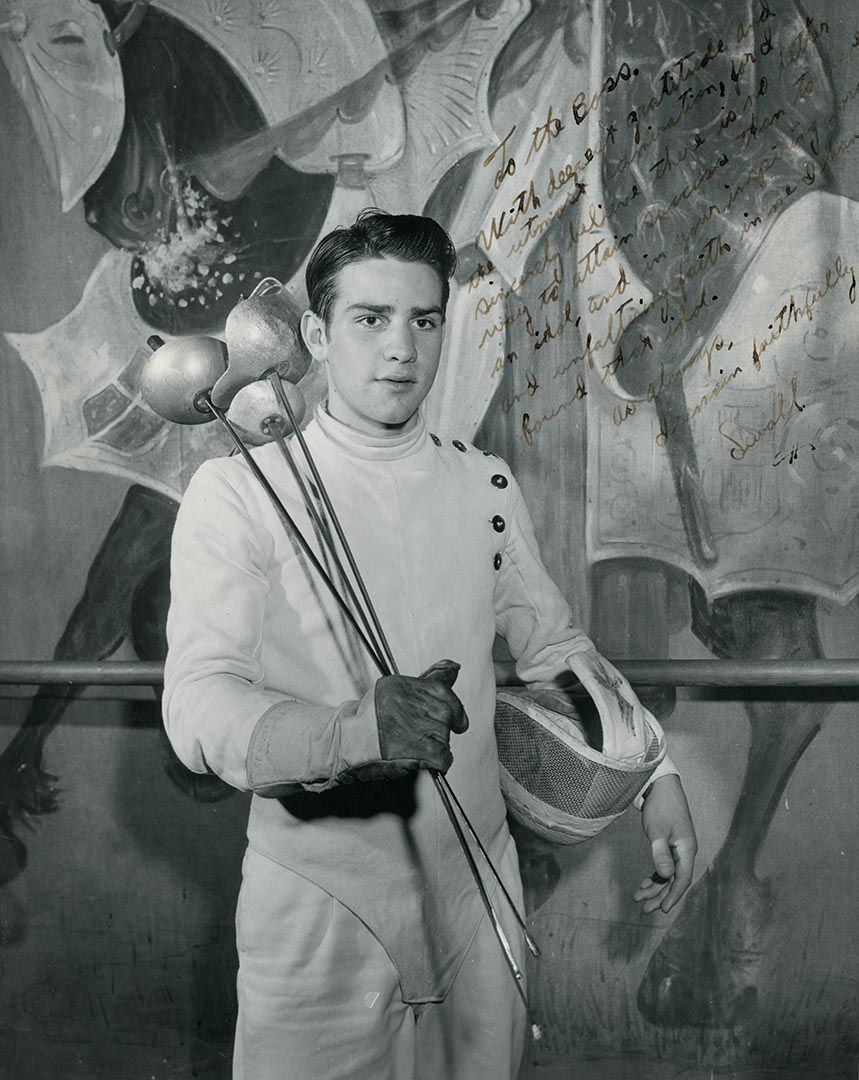

Skip’s grandmother worked as a cleaning lady for Falcon Studios, the Dance, Acting and Fencing school run by Ralph Faulkner and his wife, Edith Jane. She worked at Falcon in exchange for Skip’s lessons, and while his family hoped for the acting to “pay off”, for Skip, his interest and skill at fencing began to resonate. But the parts did come through at times, including a role at the age of 12 as one of several children in the Claude Rains film “This Love of Ours”, originally titled “As It Was Before”. News clippings and press photos also showed off Skip’s various talents. Sometimes these were put forward by agents, sometimes by schools and teachers, but all were in hopes of that elusive ‘notice’ for the young performer.

Publicity photo from the Claude Rains starrer, “This Love of Ours” from 1945. Skip, in the middle back, looks over the sketchpad as Claude draws a caricature, or rather, pretends to. Skip is playing the uncredited role of “Youngster” and had a day rate of $25.

The dynamic of a Hollywood-integrated fencing school can be different from other fencing schools. Ralph Faulkner and his wife, the dance instructor Edith Jane, courted the acting community by housing their respective classes in the same location, the Falcon Studio. Actors of greater or lesser repute would come to take dance from Edith or fencing from The Boss, punctuated by Stars that would come in to work during preparation for a film where Ralph was providing the fight choreography, something he did for over 40 films. Skip remembered a handful of the many that came through; Debbie Reynolds, Red Skelton, Cornell Wilde. This was the Hollywood club.

Faulkner had a great many publicity stills taken. This one shows off the “Falcon Fledglings” as his younger charges were known. Sewall Shurtz is in the front row, 3rd from the right with the Hollywood smile.

Falcon Studios also became a surrogate home, and Ralph a surrogate father, for young Sewall Shurtz. The activities of the fencing club were similar to the dance performances that were frequently mounted, in that the fencers would take any opportunity to publicize the sport and the studio to the Hollywood community, guided by Faulkner’s keen sense of showmanship. Skip, along with the others, took these excursions in stride as part of the trappings that accompanied growing up with the Hollywood sensibility of finding any means to showcase your skill – whatever it may be. In the midst of all this, Skip continued to pursue acting parts, but lessons from The Boss and fencing competitions began to command more and more of this personal interest.

While fencing may have been starting to occupy more and more of his time, I’m betting Skip didn’t have any trouble putting down the foils for a party where he was surrounded by the ladies. That’s how you had your birthday in Hollywood.

I was fortunate to have the opportunity to get Skip to tell me some stories. Sometimes we would talk over Skype and I’d madly scribble notes between laughs. Skip could spin a yarn, let me tell you. Other times, I’d send him a couple of questions over email and he’d respond. He’d also just get a notion to drop me a story once in awhile, typing, I think, as ideas came to him. This next bit is one of the last category. It took a fair bit of editing to piece this all together but it’s such a great story, I just have to share it with you.

So here’s Skip, in his own words with a little spelling and syntax help.

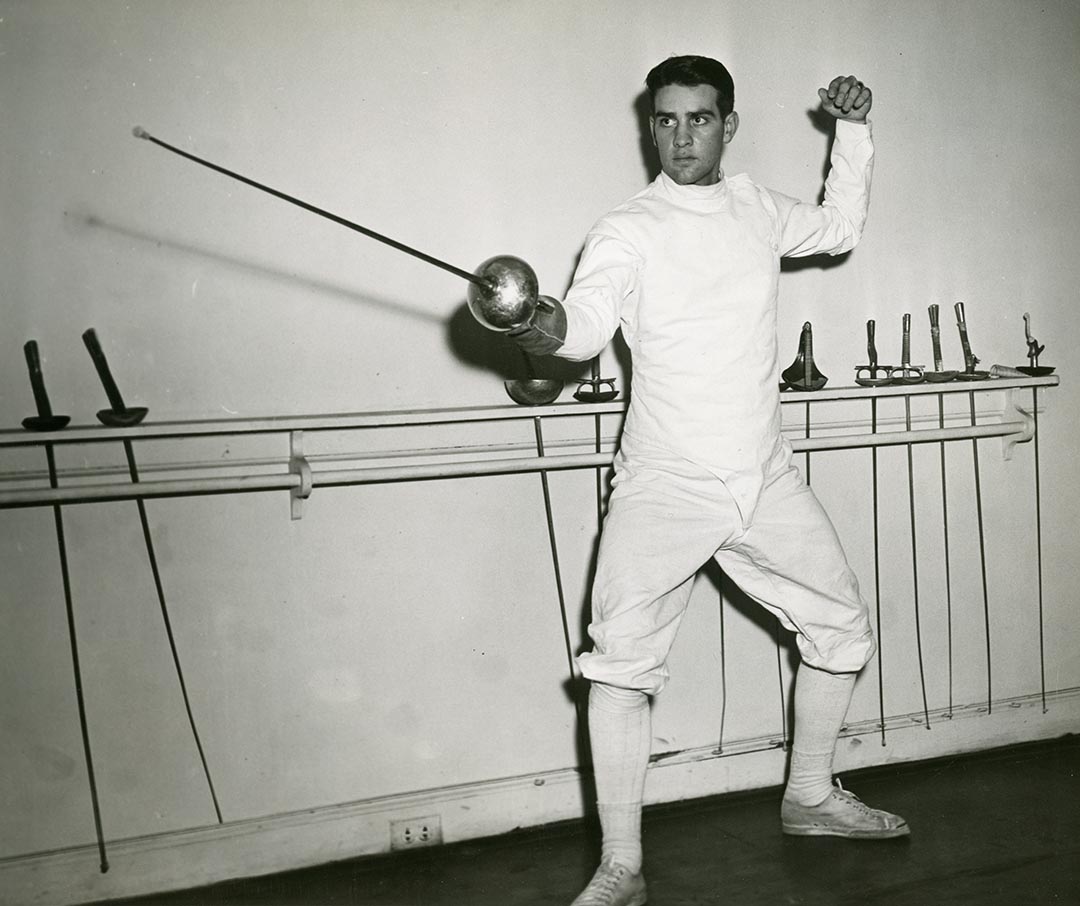

If you are going to Live by the Sword, then you must be prepared to live with the ups and downs, thrills and disappointments that will come your way. Everything is truly relative and we must each apply our own values and emotions to our lives. I was blessed in being raised by Ralph Faulkner, the Boss. I began bouting at the age of 5. And so, the process of evaluating and making judgment calls came early on. In effect, I did begin “living with the sword” early on. In the “olds days” we did not have the luxury of electric on ANY weapon. Recognize that the epee had a point d’arett?

I well remember my first epee tournament. On a Wednesday the Boss came to me and said, “You are going to fence in an epee tournament this Sunday. It is at Griffith Park and is called the Cathcart Open and is held out of doors at the park.” I thought, oh good, that should be fun, BUT I HAVE NEVER HAD AN EPEE LESSON. In truth, now that I think back, I am not certain I even knew what one looked like.

The Boss informed me that he would give me some lessons prior to the upcoming Sunday and to just “go out and have fun.” I had been in foil meets at the club but NEVER an epee. I believe I was all of 14. Well, we joined the rest of the club plus the other clubs and began our “outing.” Of course, to me, this was a TOURNAMENT. There were medals to be won! Please to remember that in those days:

1) There was NO LIMIT on the amount of point you could have showing AND no way to gauge its sharpness. Obviously, the sharper and longer the better and the greater probability it point would penetrate and be a touch, and

2) there were no divisions as we know them now. Senior, Intermediate, Junior, Novice and Prep. That was it for ALL ages. No quarter was asked and NONE was given. Most assuredly, NONE by me.

When the pool got to within my having two bouts to go, I had only to win one and, should I lose the last one, I would STILL be third. The Boss had outfitted me in new fencing pants and 12 oz jacket. No matter, shortly after the bout began, my opponent, from the LAAC made long lunge which went through my jacket, across the right side of my stomach, hooked the left side of my stomach and opened me up like a Christmas turkey.

The wound, I came to learn, was 5 inches long and, as luck would have it, stopped just above the intestines. As I lay on the ground with a towel wrapped around my stomach the Boss came to me and said “If you had parried, that would not have happened.” The next day I was to enroll at Hollywood High. We had no money for a Doctor so I went to the school, towel wrapped around me, under my shirt confident in the knowledge that The Boss would pick me up and be there for me. The Boss had taken me there, waited for me, and after registering, took me to a doctor to sew me up. Time having passed, the edges of the wound had begun to curl. All of which was part of getting sewed up. I look back and other of us “Old Timers” compare our warrior epee days prior to electric.

No, they did not let me fence for third place.

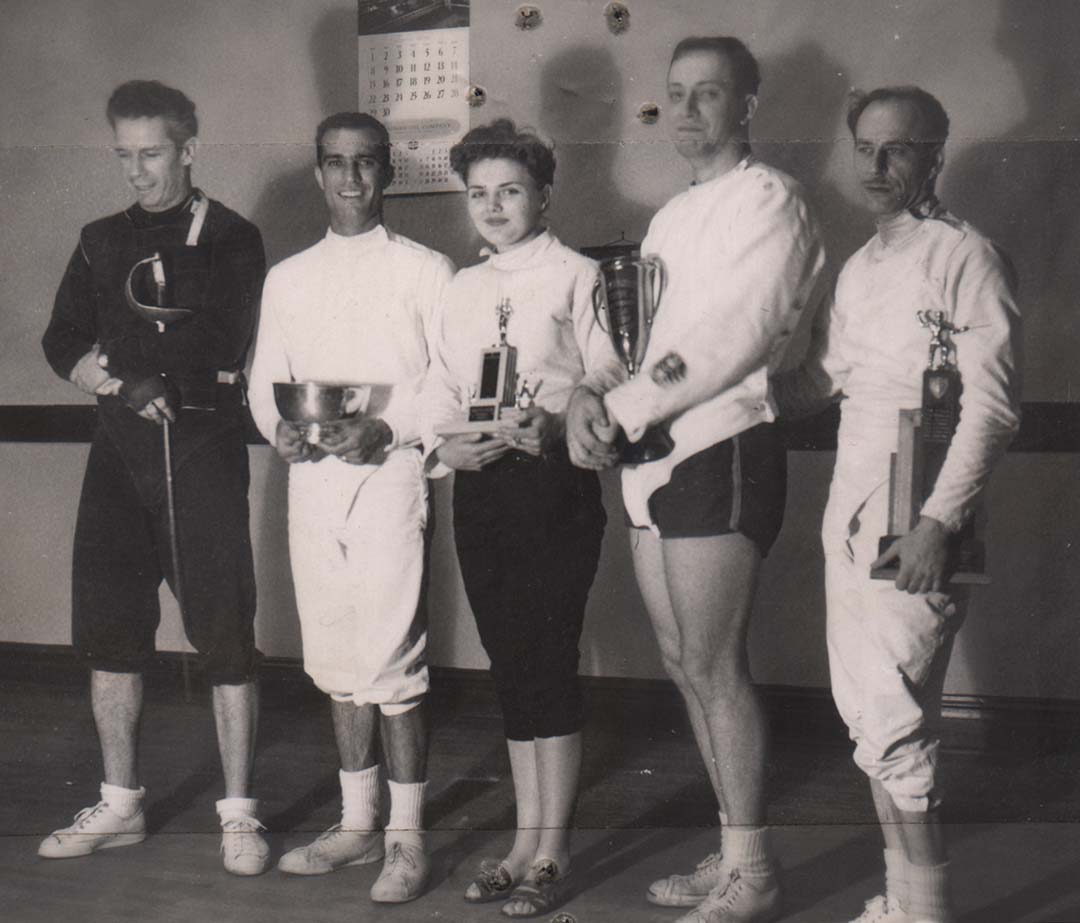

Skip, above left, after winning his last match in the 1954 US National Championship Men’s Epee finals, the first of his two championships. Two years later, he won the Men’s Foil.

So there’s a sample of Sewall “Skip” Shurtz as a storyteller. He had some good ones to tell, make no mistake.

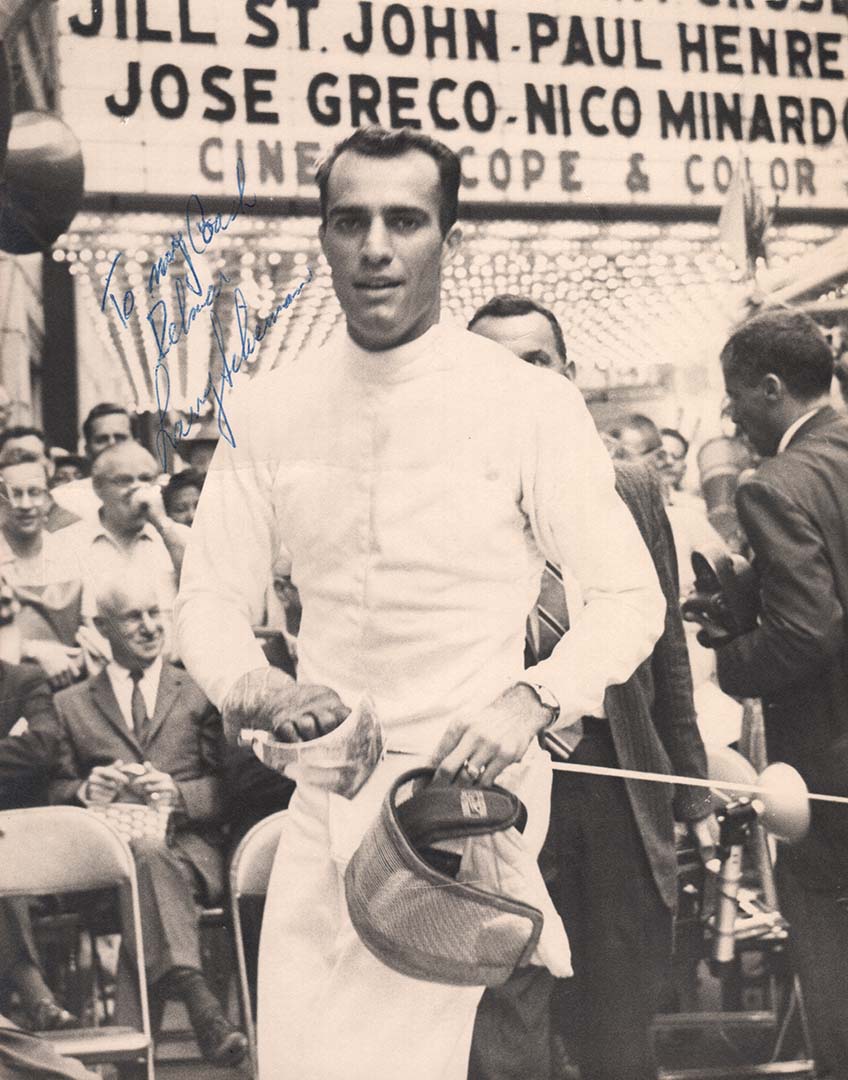

As an added bonus, I have one photograph from the Cathcart Open, which was always held at Griffith Park. I used to work a couple of blocks from this part of the park.

The Cathcart Open epee competition. This is a different year than the story above but that’s Skip on the right going for the stop hit on the exposed shoulder.

And, as an extra special treat, I rousted around in my bin of movie clips and came up with this one – a little piece from the home movies we rescued from the dumpster at Heizaburo Okawa’s house. This film clip was shot by a member of the Mori family and shows – quite possibly – the same tournament as the photo above. Only in color! I’ve added a few titles to put names to the people that I could identify. Skip can be spotted throughout due to the tape over the top of his mask but it starts right out with him saluting with his mask off. So here’s the Cathcart Open epee competition, non-electric, being held in Griffith Park concurrent with a women’s foil event. This film reel isn’t dated but my estimate is 1955 or 1956. Skip used this same mask with the tape over the top at the 1956 Melbourne Olympics.

Party Like Hans Halberstadt

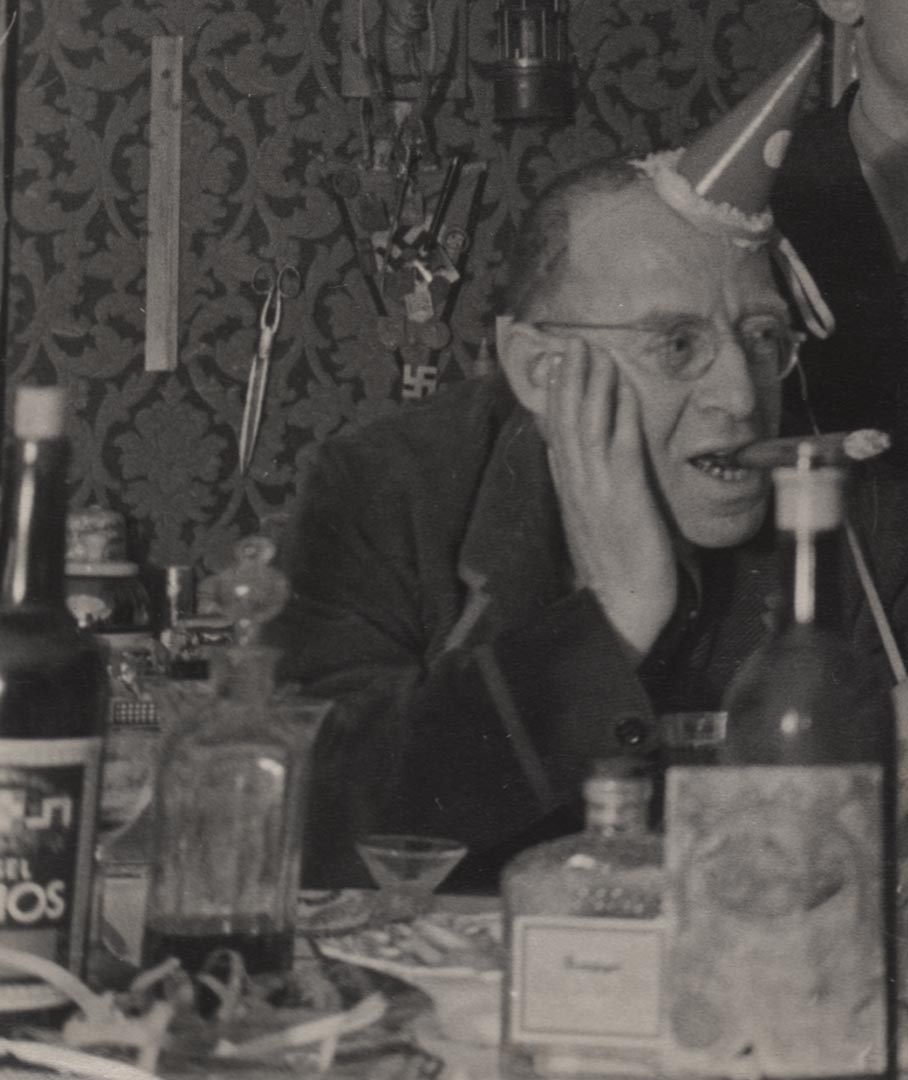

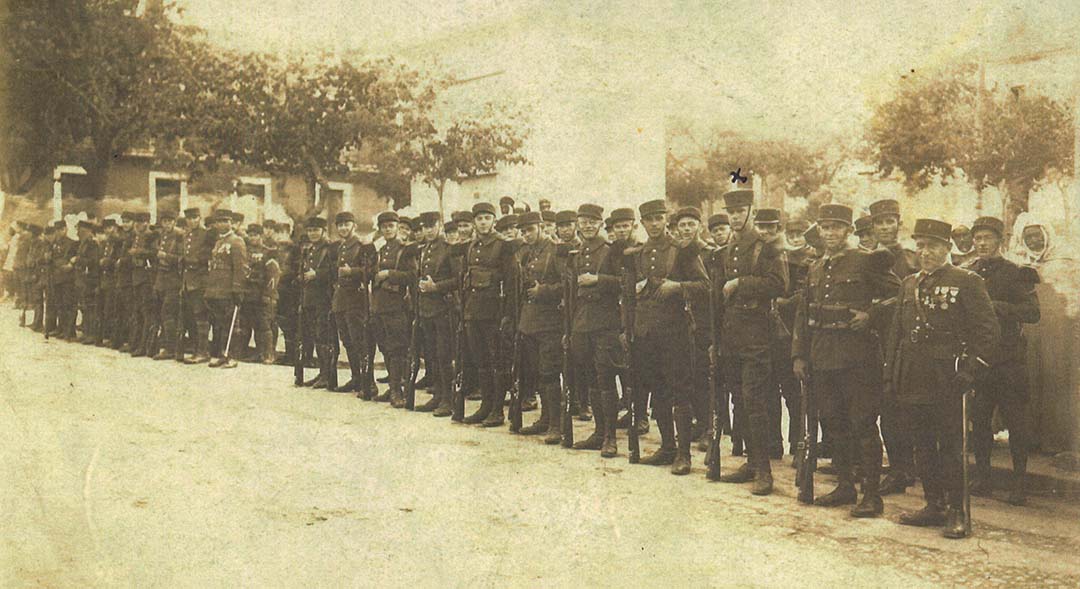

Of the 13 million Germans mobilized for the First World War, over half were killed, wounded or taken prisoner. Hans Halberstadt and other survivors jumped into the Roaring Twenties with gusto. A decorated war hero, Hans came back home to Offenbach en Main and the family’s very successful leather goods business as a man of leisure. Years later, he would boast to his students in San Francisco that he had kept fencing gear in lockers at all the best fencing clubs in Europe so that he needn’t take equipment with him when he traveled for competitions. In looking over the photos I’ve selected to share today from the Archive’s large collection of Hans Halberstadt ephemera, it’s really not hard to believe. Hans and his friends had fine clothes, the best drink, hired photographers, and dressed in costumes just to add another level of frivolity. The seriousness of the war years behind them, they partied like rock stars.

In none of these photos do I recognize any other fencers, and I’ve gotten pretty adept at recognizing several of his teammates. Hans either kept his worlds separate, the fencers didn’t have the means to keep up with him, or his salle-mates were camera shy. Impossible to know of course but it seems clear that Hans ran in a fast circle. And maybe he was the wild man off the piste and showed up to tournaments hung over when ultimately taking second place to Erwin Casmir, as Hans did at every German championship for nearly a decade. (In fact, Casmir was just that much better than Hans and all but a handful of fencers on the international scene.)

These photos mostly come from what I lovingly refer to as the “Hans Box”. (See the story here.) In short, the box sat unopened for several decades in the possession of Charles Selberg and was full of Hans Halberstadt family photos, personal photos – many of girlfriends, if I was to guess – and scads of people I can’t identify. Among them were a whole bunch of photos like the below. Party pictures. Hans and his cronies working hard to secure the reputation of the 1920s as a hedonistic and unrestrained period between war and depression, then war again. If they felt it all coming their way, it doesn’t show.

I was prompted to put together this post after sharing a lovely meal with the venerable fencing entrepreneur and master, John McDougall. His collection of fencing memorabilia came to the Archive sometime near the beginning and he recently ran across a few items that were uncovered during a deep clean of his digs. Among them, three of the photos you’ll find below. All three, Hans party pics. Combined with several of the party photos from The Hans Box and it creates a pretty interesting picture of what exactly Hans was up to in his years after the war. He fenced, traveled, competed at the Olympics – and partied.

There’s not a whole lot to say about the individual photos. They speak for themselves, seems to me. I’ve got a few notes to add as you’ll see. Here’s the first batch.

Hans Halberstadt among the ladies.

Hans, front row far right, literally kicks up his heels.

Draw your own conclusions on this one.

Hans, far left, didn’t seem to go in for costumes so much but he sure was a snappy dresser. I wonder if that tux has tails?

Hans again on the far left with his most constant companion, a cigar.

These next three all contain one party goer who’s outfit makes her recognizable, inasmuch as I can tell it’s the same woman. No idea who she was, or what she may have been to Hans. Since she can been seen in the same costume in all three photographs, it seems fair to assume they were all taken at the same party.

This seems less costume party and more fancy dress party, although the woman we’ll see in the next two photos, here to be seen on the far left, is sporting a frill and cloth buttons that almost make her outfit clown-like. Of course, that might be a description she would have taken offense to, and I’ll make no claim to the eye of a Michael Kors to be critiquing anyone’s sense of style.

…although with this photo maybe my clown interpretation hits a little closer to home than not. Hans appears to be in his element here. The recognizable woman above on the left again.

And here it’s just the two of them. Friend? Paramour? An acquaintance made that very day? Who knows?

Whatever the fun, however long it lasted, it eventually came crashing down for Hans and his life in Germany. The next photo, knowing the fate that was around the corner for Hans and so many Germans, always takes my breath away. Take a look and I’ll explain.