I remember James Burke’s late 70’s TV series very fondly but haven’t watched an episode in a very long time. I wonder if it holds up? Burke, in my memory of the show, had a unique ability to trace the origin of modern technology back to inventions from ages past, noting how seemingly insignificant developments in one area would lead to the next leap forward somewhere else. A recently-made connection to the family of Los Angeles Athletic Club fencer Andrew Boyd got me thinking about it.

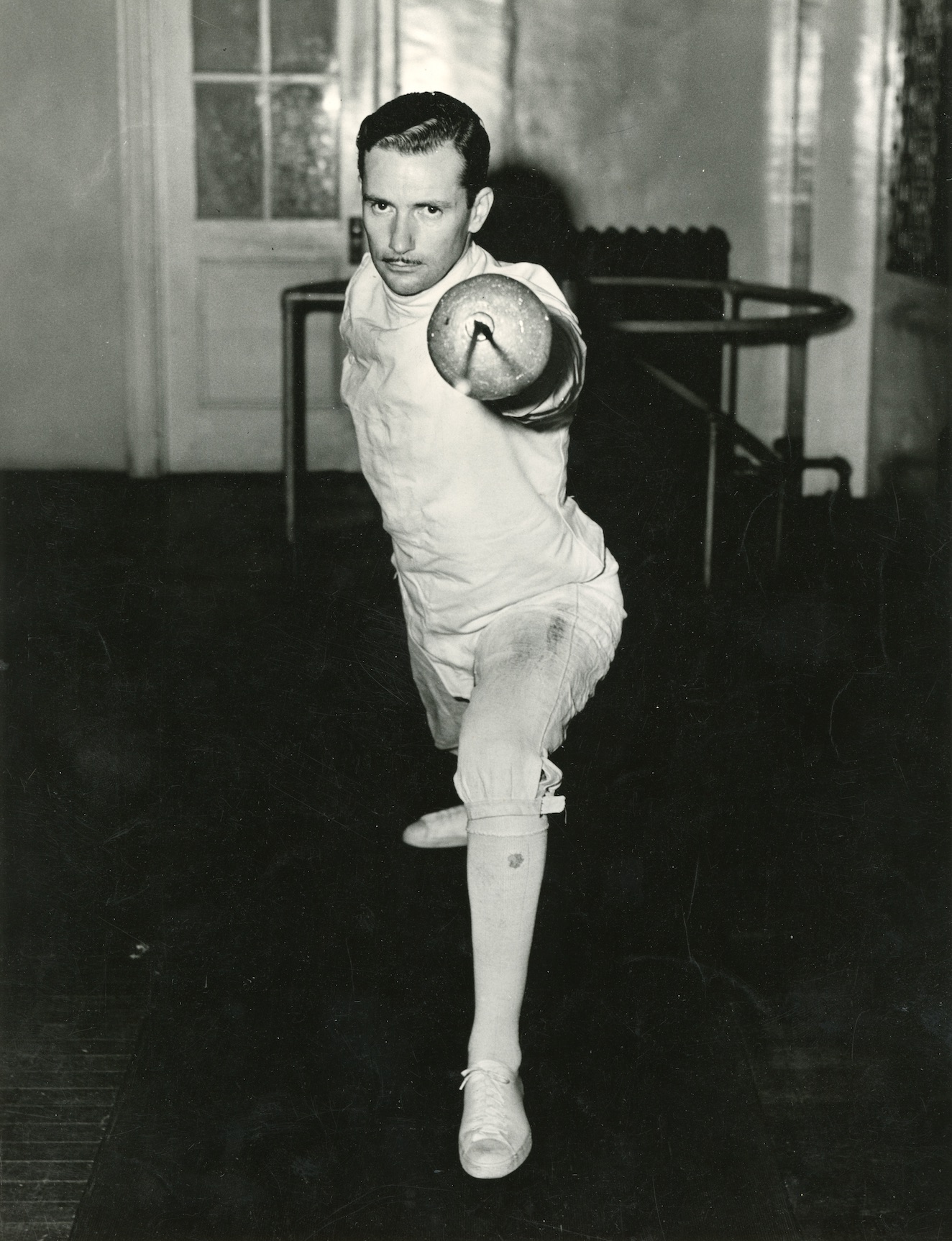

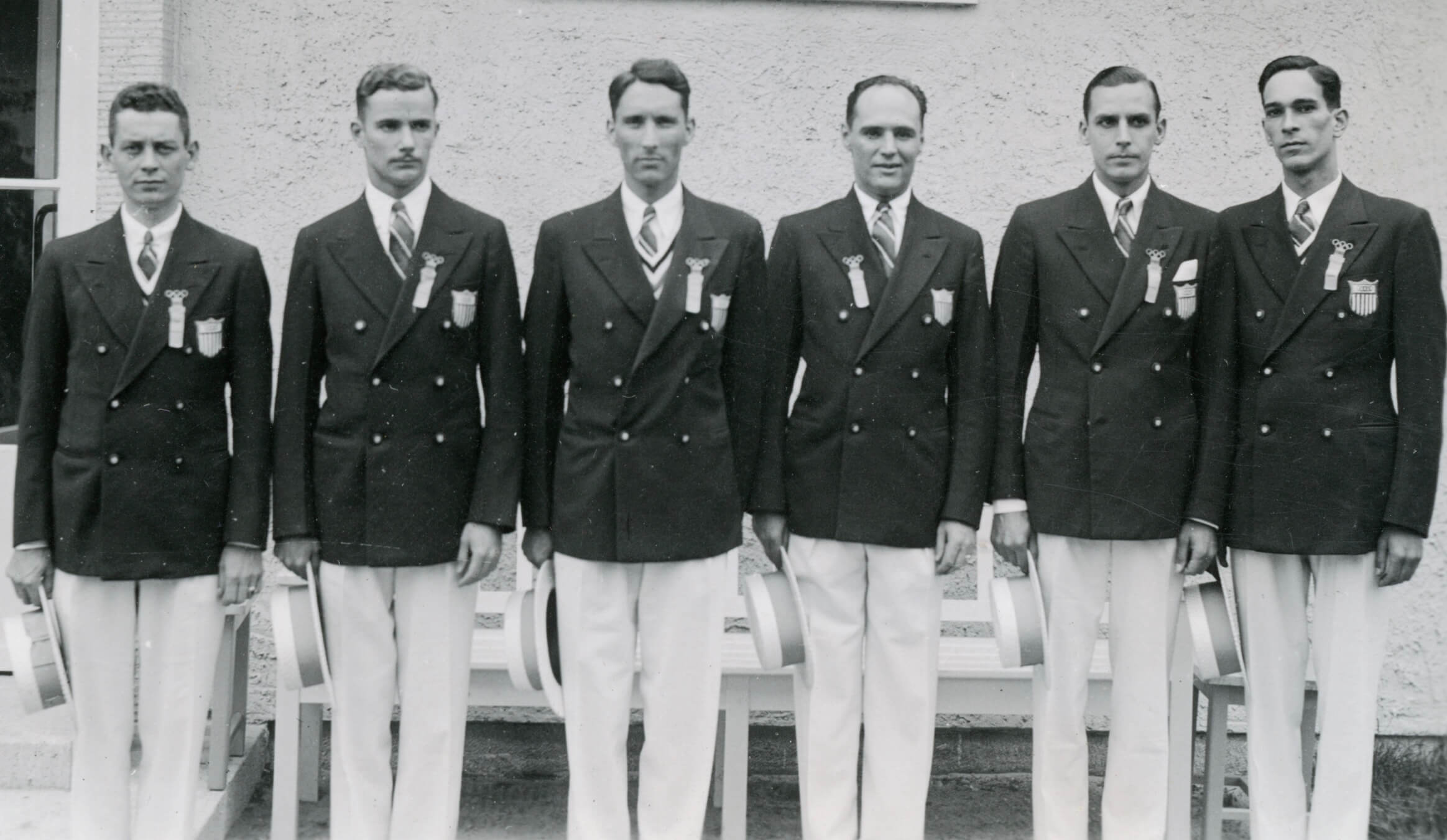

Andrew Boyd in an undated photo. Likely from 1936.

Andrew Boyd was a fencer I have wanted to know more about for quite some time now. His name appears regularly in tournament results dating back to the early 1930s and continued until the early 1960s. His teacher was the great – and I’m getting more and more information to back up that pronouncement – Henri J. Uyttenhove, long-time Los Angeles Athletic Club Maestro, to say nothing of his teaching at the Hollywood Athletic Club, The Pasadena Athletic Club, USC, UCLA and his own private club in Pasadena. I wonder how he got around so much? The Arroyo Seco Parkway, now the 110 freeway, didn’t open until 1940 and Uyttenhove started his Pasadena Club and his gig at the LAAC around 1910. It’s entirely reasonable to imagine that he traveled throughout Los Angeles County on the Red Car, a fabulous mass transit system now mostly remembered as a featured element in the plot of “Who Framed Roger Rabbit”.

Andy Shaw at the Museum of American Fencing had a couple of pictures of Andrew Boyd and a little bit of information. There is also data to be mined by perusing back issues of American Fencing Magazine for tournament results. It’s there I learned that Boyd was still making the semi-finals at Nationals until 1961 – at 51 years of age. It’s a little more challenging getting results from the 1930s. American Fencing Magazine didn’t begin publication until 1948 and finding old copies of The Riposte Magazine or the AFLA Secretary’s Newsletter are even more challenging to track down. Another good resource is one I’ve mentioned several times in past writings, The Fencer magazine, but its short run gives it a limited range of usefulness. With one thing and another, I’ve been able to glean quite a bit of info on Mr. Boyd and his competitive successes. I also knew when he was born and when he passed away, but nothing else.

While trying to find out more about Boyd, I hit upon the idea of sending an email to the city clerk of his former town, which I found on Wikipedia. I got an email back right away from the clerk who didn’t know anything helpful for my search but knew someone who might. Later that same day, I received an email from Andy Boyd – the son of Andrew Boyd the fencer! Can I just say, I love small towns. Everybody knows somebody who knows everybody.

After a series of back and forth emails, I determined to take a drive over the mountains – through Yosemite, actually – to the Owens Valley and meet the Boyds. Come to find out, Andrew the elder had several children and grandchildren who were all well-versed in the story of their Olympian family member. Andy had a weapons bag, photos, news clippings, trophies, even a home-made scoring machine, although the wires have now been pirated for some other project. They allowed me to scan and photograph to my heart’s content and now I can share some of the story and other highlights from my visit.

Andrew Boyd’s homemade scoring machine for epee. Note the two lightbulb sockets on the top. At a guess, I’d say the doorbell buttons must have been rigged to ring the bell at the same time the lights fired. (“Is someone at the door?” “No, I’ve hit you in the elbow!”) Probably not the most sophisticated scoring box ever made, but it probably came in handy in 1935 or thereabouts when official devices were scarce.

Boyd was selected to the 1936 Olympic team and was the only SoCal representative on that team. Based on other research I’d done I had to wonder why he was the only Westerner on the team, so I did some digging.

Andrew Boyd, 1936

Let’s talk politics. No, not today politics. Ancient fencing politics. Back in the days of yore, the East Coast hegemony ran things. That’s just how it was. They founded the organization, they made the decisions. Now, the Pacific Coast section was the largest section outside of Metropolitan New York. Both the Nor Cal and the So Cal divisions had good numbers of members back in the 1920s and 1930s. However, when it came time to do things like, oh, you know, choose the members of the Olympic Team, let’s just say the West Coast contingent didn’t get much consideration from the selection committee who, need I mention, were all from New York and mostly from the NYAC. This caused no small amount of frustration for folks who fenced at places other than the New York Athletic Club. This bubbled over in the lead up to the 1928 Olympics. The West had some pretty good fencers, but the New York powerbrokers didn’t really imagine giving up Olympic spots to West Coasters in place of their friends & teammates. After the ’28 Olympics, to quiet the hubbub the New Yorkers decided to settle the matter on the strip. They put a bunch of their best fencers on a train headed west and challenged the noisy Californians to put up or shut up. The results ended in a decidedly different manner than the New York contingent expected. Only one fencer from the East, sabreman and famed photographer Nick Muray, went home with a medal, and it wasn’t gold. Having demonstrated their mettle, the West was granted a path to the Olympics. The top finisher in each weapon at the Pacific Coast Championships would be granted a spot on the team. This upped the ante for PCC participants, to say the least. And in 1932, this led to the inclusion of the top West Coast talent: Hal Corbin epee, Ralph Faulkner, sabre, Ted Lorber, foil.

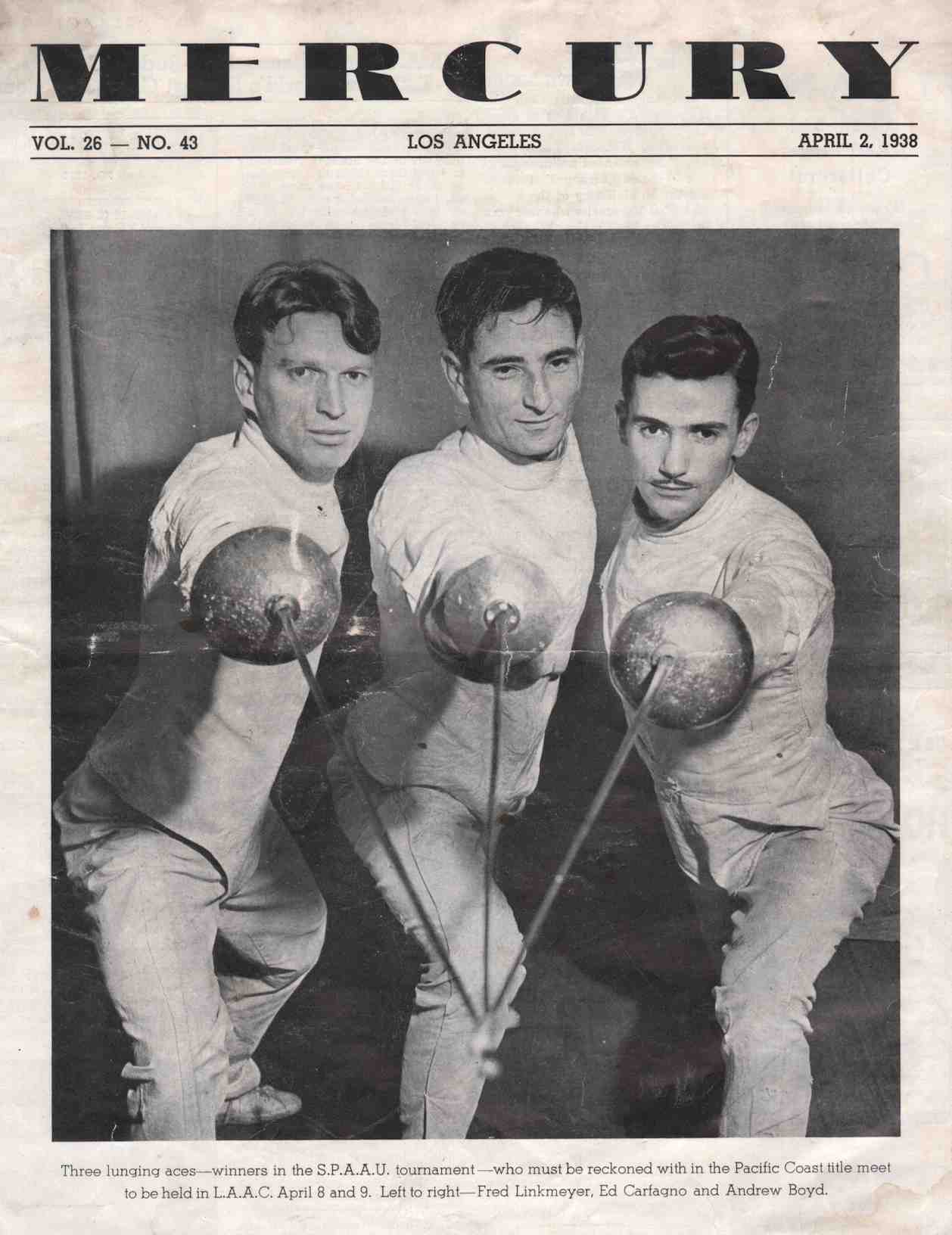

Fred Linkmeyer, Ed Carfagno and Andrew Boyd. Carfagno won the Silver medal in foil at the Nationals in 1939, the year after this was taken. Like Boyd, he was a likely candidate for the cancelled 1940 Olympics.

For reasons lost or obscure, this set of rules were altered slightly for the selection of the 1936 team. Only one West Coast fencer was picked for the Berlin Olympics. Andrew Boyd. In reading some news articles from the period, it seems that the New Yorkers added a new wrinkle to qualifying for the Olympic berths. That wrinkle was to require attendance at pre-Olympic training sessions and competitions to prove yourself worthy of consideration. And guess where all the training and competitions were held? If you guessed anywhere other than Metro NY, go back three spaces. Ostensibly, this was to ensure that the selected fencers would be in good training and top form for the Games. That notion is commendable, of course. But in practical terms, it meant anyone with the credentials to compete had to be in New York for an extended period of time, a challenging requirement for people living and working anywhere other than New York. However, Andrew Boyd was able to ‘beat the system’ as it were. He was working at that time for a company with a New York office. When he informed them that he had a chance for making the Olympic team but needed to be in New York to compete and train, they transferred him to New York. That put him in the right spot to not only get in on the training and competition, but also get to know the ins and outs of the New York crew. When the penultimate selection competition came around, the US Nationals in 1936 – in New York – he finished in 3rd place, securing his spot on the team.

Left to Right: Thomas Sands, Andrew Boyd, Gustave Heiss, Frank Righeimer, Tracy Jaeckel, Joe de Capriles. These six made up the 1936 Men’s Epee team. Not pictured is Frederick Weber, a member of the modern pentathlon team and a top epeeist who, along with Heiss and Righeimer, fenced in the Individual epee event but not the team event.

But if you imagine that to be the end of the politics, think again. At the Olympic Games, he was kept out of the individual event by the choice of the captain following a vote among the team members. For the team event, they started without using Boyd until they faced Sweden in the semi-finals – a match the US didn’t have much hope of winning. (The Swedes went on to beat France for the Silver medal.) Boyd was thrown in for his first Olympic matches and promptly won two bouts and tied a third, giving him the best record for the US in the match. The US went down 7 wins to 8 for the Swedes, Boyd’s tie match counting as a null or half-victory. A shortened Olympic experience for Boyd but one wherein he proved he could stand up against anyone.

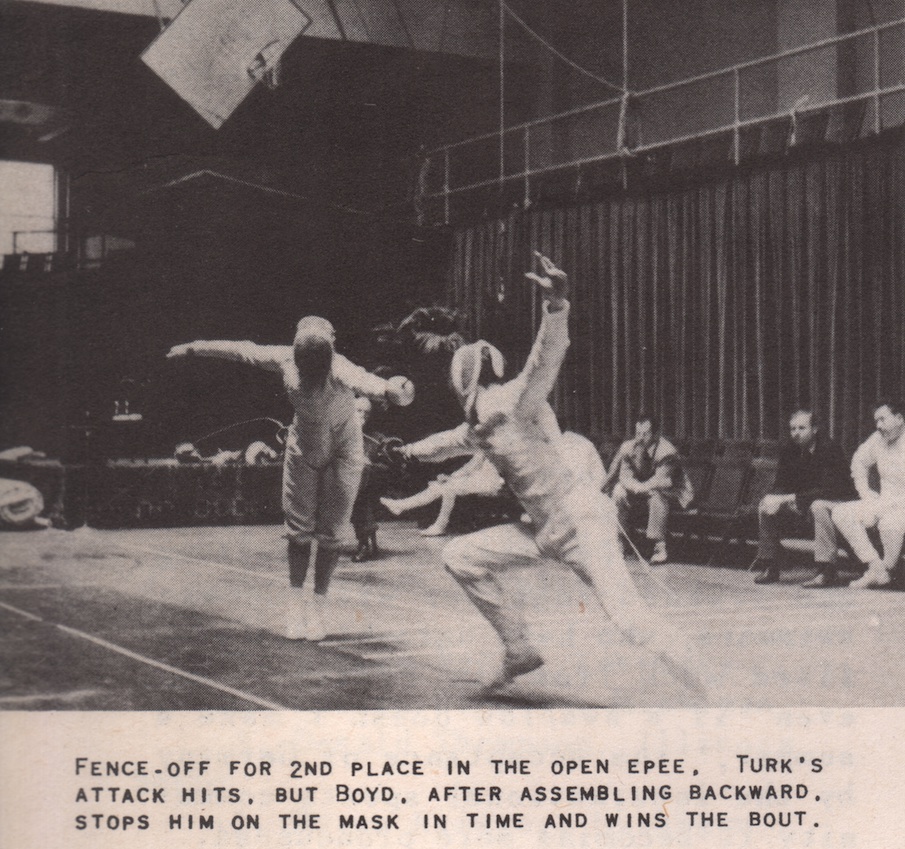

From The Fencer magazine.

Andrew’s early days of fencing are obscured by the years, but the family tells the story of how his mother didn’t care for him running track due to an abundance of caution concerning his health. Remember that this was a time when running in a marathon was, in the view of some, a life-threatening undertaking. How fencing became the safer alternative, sadly, we’ll never know. Uyttenhove was his coach from the beginning, likely at the Los Angeles Athletic club, although it’s possible Uyttenhove still maintained his salle in Pasadena which he opened sometime around 1908. I have yet to find a record of when that club closed, or where it was located. The Boyd family lived in both Pasadena and Altadena and Andrew was born in 1910, so he would have likely begun fencing in the late-20s or early-30s. Andrew represented the Los Angeles Athletic Club throughout his competitive career. Located in downtown LA, the LAAC was a short Red Car ride from both Altadena or Pasadena on the Downtown line through the Arroyo Seco, then a quick transfer onto the Main Street line to 6th Street. Jump off at Olive and you’re half a block away! I have no idea how long that took. By car it’s probably a half hour with no traffic and there’s always traffic. The old maps of the Red Car line don’t indicate time for distance traveled.

After the 1936 Games, Boyd remained in contention and received several letters in the run-up to 1940. Until 1939, there was still some thought, if little hope, that there might be an Olympic Games, so sports governing bodies were continuing to pursue qualifying until the Games were officially acknowledged to be off. After the war, he continued to compete and was named to the 1948 London Olympic team.

Relaxing with the 1948 team in London. Boyd is on the far right in the Hawaiian shirt. Next to him, furthest right, is Team Captain Salvatore Giambra from San Francisco’s Olympic Club. Dernell Every is the one twisting around to look over his shoulder and 3rd from the left wearing glasses is Tibor Nyilas who helped the sabre squad to a Bronze medal.

The LAAC teams led by Boyd and long-time sallemate Fred Linkmeyer dominated the West Coast for years and Boyd’s name continued to be mentioned as a contender for many years. By the mid-1950s he wasn’t attending the Nationals every year but every now and again he’d show up for the team event, as in 1959 when he and his LAAC team took 3rd in Team Epee. He was still considered enough of a player to be named a member of the Olympic Squad prior to the selection of the 1960 team.

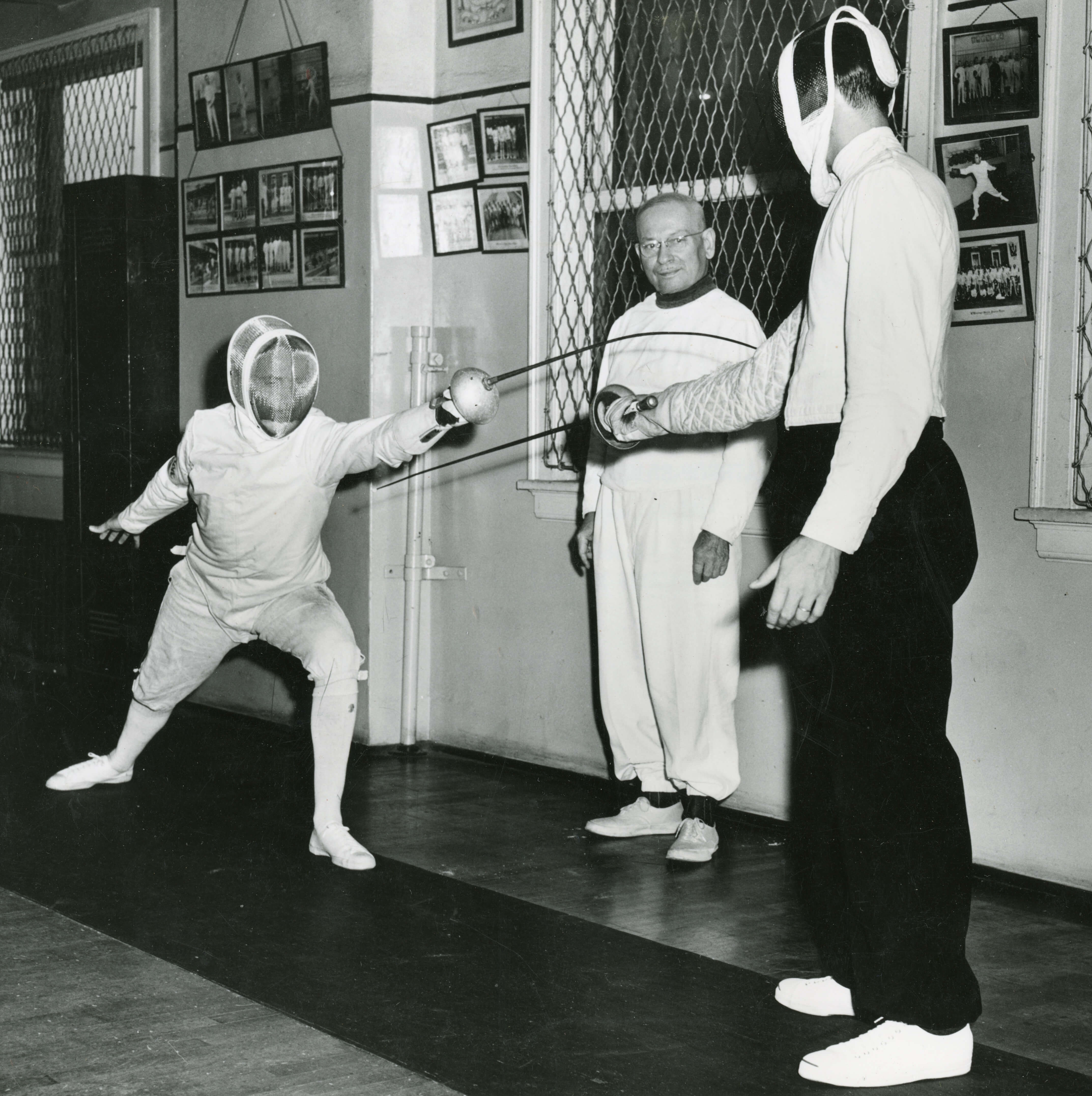

Andrew Boyd lunges and hits Fred Linkmeyer at the LAAC while Henri Uyttenhove observes.

One last story. If you’ve been following along with the Archive, you may have seen the story about Captain John Duff. (If not: here it is.) Sometime prior to leaving Southern California around 1932, Duff created two prizes for two separate tournaments to be held in his name, the Duff Epees and the Duff Foils. The epee event was for the menfolk and the Duff Foil was a women’s event. Duff had beautifully engraved matched pairs of foils and epees created as the prizes for the events, along with a very interesting stipulation. That was, whoever could win the event in three successive years would win the prizes outright. For keeps. I’m not certain when, or if, the Duff Foils were eventually awarded permanently. In fact, the foils event was the first mention I ever read about in my copy of The Fencer magazine. (The Fencer, part 1)

Here is the quote from The Fencer, October, 1946:

“The contest dates back to 1936 when Captain John Duff presented a matched pair of decorative foils as trophies for a summer women’s competition, and a similar set of dueling swords for a men’s epee event. The prizes were to be retired by any fencer winning them for three successive years. The Duff Swords were retired by Andrew Boyd of the LAAC after the first three competitions, but the Duff Foils are still being fought for.”

The dates here may be a bit off. The Boyd family was kind enough to make a donation to the Archive of some documents, and included in that packet was a note that Andrew had already taken possession of the Duff epees by 1936, having won the first three runnings of the Duff epee competition.

Now, let’s face it. There isn’t a great deal of competition for me in this realm of researching the history of fencing on the West Coast. But I’d read the above passage about the Duff epees a year or two prior to my first introduction to the Boyd family, so I knew what the Duff Swords were. At least, the knowledge floated somewhere in the not-too-distant recesses of my noggin. But when I went to visit the Boyds, one of the very first things Andy asked me was, “Now, have you heard of the Duff Swords?”

The highly engraved Duff Dueling Sword. The matched pair came with scabbards as these are sharp swords, not fencing weapons. Over time, the leather of the scabbards has worn away although the family still has all the pieces.

I don’t know how many folks today could have responded in the affirmative to that question about a fencing tournament trophy taken out of circulation around 1936. It seems that so much of what I find myself doing is reading an article or caption, maybe seeing a picture, then sometime later these disparate moments and elements wrap together giving clarity to a larger historical context. And so, I keep reading and looking at the scads of material I’ve been collecting, knowing that I can’t predict which item six months ago or six months from now might suddenly connect to another piece of the puzzle. I wonder if that’s how the TV show was created? The idea appeals to me, that’s certain. Making connections to fencing history may not pay well, but rewards are there nonetheless.

Getting to hold one of the Duff Swords? Now that was a great connection.

holy mackerel Doug! I’m gonna follow you now for sure

Great! You’re my target audience!

Hi Doug Nichols, this is probably a long shot but… any chance that Andy Boyd shared with you other pictures taken during the London Olympics in 1948? In the above photo captioned “Relaxing with the 1948 team in London…”, the person 2nd from left (in the striped shirt) is my late father, Don Thompson. He was the youngest member of that Olympic fencing team. I was just wondering f you have any other pictures that might include him, and wouldn’t mind sharing them with me.