As a member of the Hall of Fame committee for USA Fencing, I get a chance to participate in an annual ritual of determining, in the fairest way possible, who is to be considered for inclusion into that prestigious body. But in the long run, just like every member of USA Fencing, I only get one vote. However, if my website is good for anything, it’s good for providing me a bully pulpit from which to tell stories to keep alive memories of fencers who deserve to be remembered.

So please. Let me talk story to you about Dan Magay. (I’ve told part of it before: Dan pt 1.)

In 1956, as the Olympics were playing out in Melbourne, Australia, a much more dramatic, world-changing event was playing out in the streets of Budapest, Hungary. The Hungarian Revolution was crushed by the Soviets and hopes that Hungary might join the world community beyond the Iron Curtain were dashed. Just as the Hungarian Olympic athletes had to individually determine their future, so, too, did the Hungarians back home. In the end, hundreds of thousands of Hungarians escaped during the time right after the Revolution ended. At the same time, a plane full of Olympic Athletes flew from Melbourne to San Francisco. With all the myriad changes made in the lives of all these refugee, as well as the changes to America and American society that resulted, the impact upon the American fencing scene can’t be overstated.

In particular, American sabre fencing was remade overnight. Coaches George Piller, Istvan Danosi and Csaba Elthes were hugely impactful. And the list of competitive fencers is like a Murderer’s Row of talent. Alex Orban, Tom Orley, Atilla Keresztes, Eugene Hamori, Csaba Pallaghy, George Domolky – all of these fencers finished up and down the list of National Sabre finalists for the next 15 years. But the best of them all was Dan Magay.

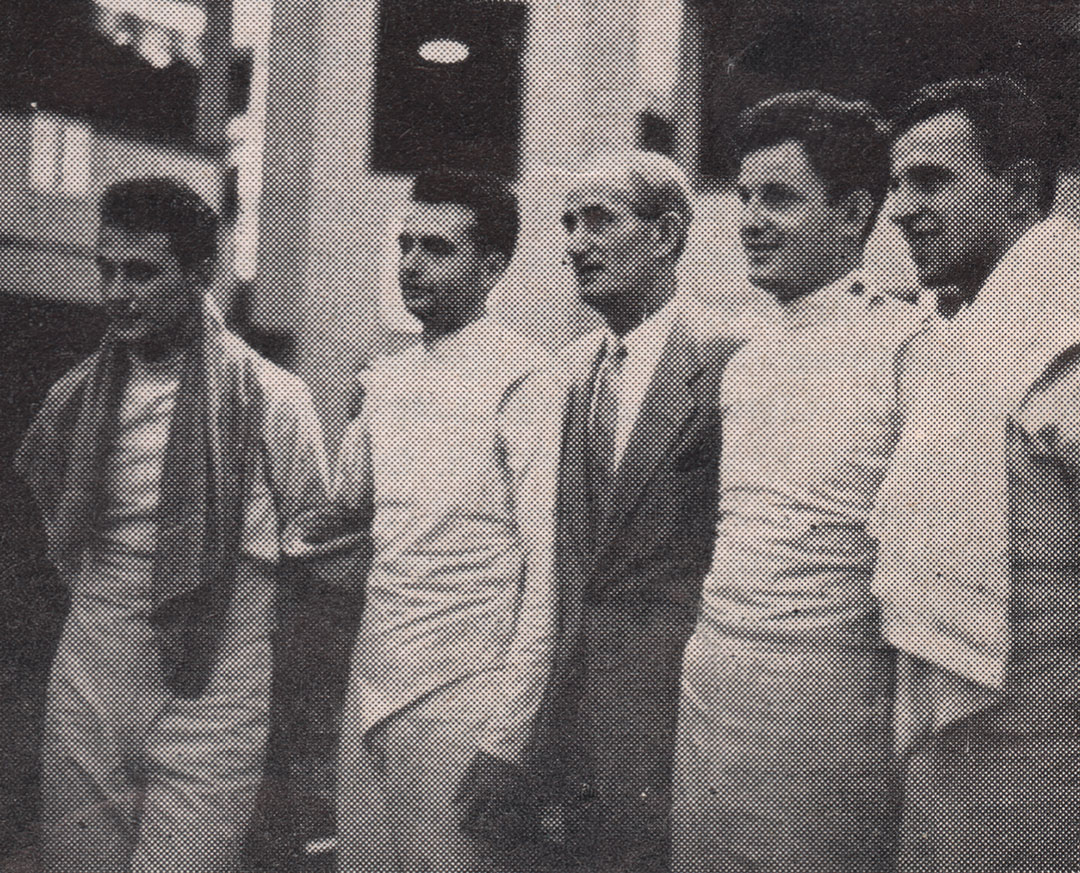

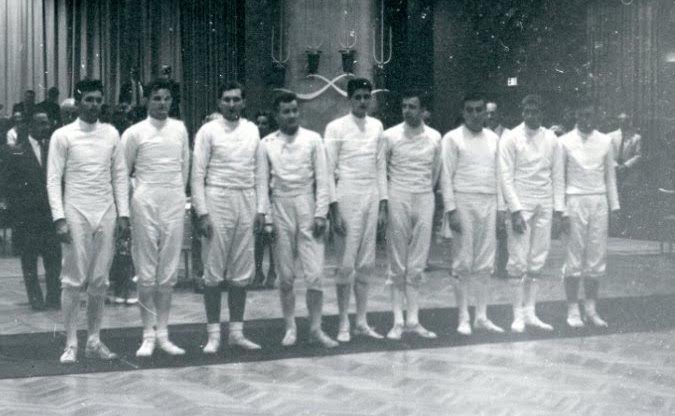

A fencing version of Murderer’s Row: Tom Orley, Dan Magay, George Piller, Eugene Hamori and Csaba Pallaghy. Taken at the 1958 Nationals.

“Dan was who I hoped to emulate.” Alex Orban said that, he of five US National titles and three Olympic team berths. Long time Magay club mate Gerard Biagini put it this way. “Dan was the epitome of what a sabre fencer wanted to be.”

Magay immediately made his presence felt at the very first post-Hungarian Revolution US Nationals in June of 1957, defeating 7-time US sabre champion and Olympic Bronze medalist (team), Dr. Tibor Nyilas and 1954 Junior World Champion Tomas Orley in a 3-way fence off. Magay dropped only one bout the whole day, to teammate and childhood friend Orley, in the final round-robin pool of twelve fencers, going 22-1 for the event. His Northern California team, consisting of himself, Orley and George Domolky – and coached by Piller – won the sabre team title as well. When deciding to travel from their new home in California to Milwaukee for Nationals (they bought a used car and drove), Domolky asked Piller if the three teammates had a chance to win. He answered simply, “Don’t worry.”

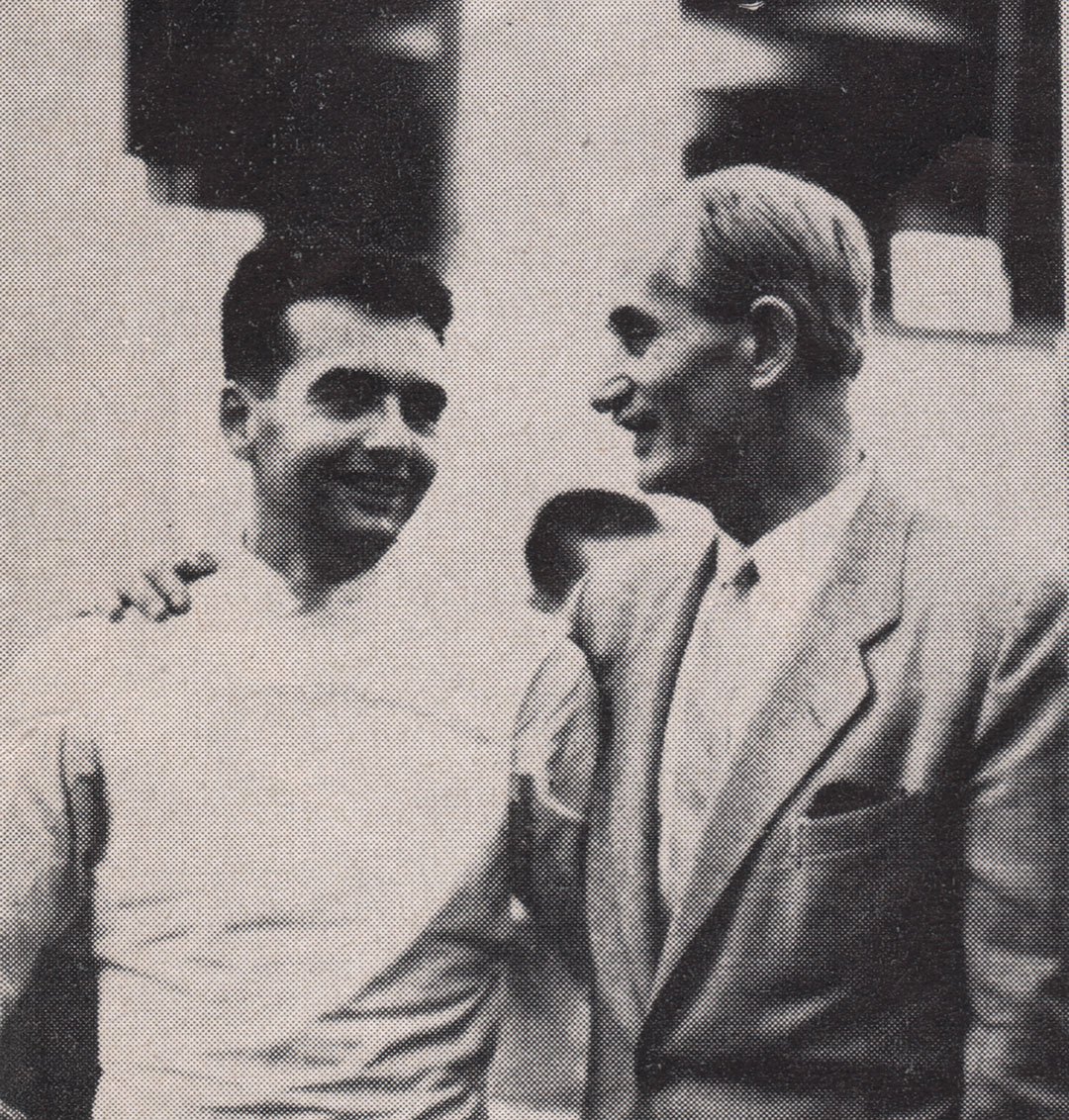

Magay with his Olympic coach, Jekelfalussy Piller György, himself a World Champion and Olympic Gold Medalist in sabre.

All this happened just a few months after the conclusion of the Freedom Tour, a whirlwind nationwide whistle stop that started in New York and ended in San Francisco, where Hungarian athletes put on demonstration events at 25 venues from January to March of 1957.

The Freedom Tour program cover. Sports Illustrated not only paid for the tour, they were the ones who chartered the plane that flew the Hungarian athletes and coaches from Melbourne to San Francisco.

Magay, Domolky, Hamori and others participated in this while trying to decide their future in their new country. Recruited heavily as they traveled from city to city, Hamori settled in Philadelphia. Orley and Domolky received admission to Stanford. Magay, through the assistance of an acquaintance, was accepted into UC Berkeley.

Dan as a student at UC Berkeley, where he studied Chemical Engineering.

Between school and work, training in fencing took a back seat in all of their lives. This, after living in a situation where fencing was their entire life, was the new model for survival. In Hungary, Magay, alongside Hamori, Keresztes, Orley, Pallaghy and Domolky, had been among the elite athletes, training and fencing full time in preparation to step up to replace the older generation of fencers who had dominated the world sabre scene for decades. The Big Three in Hungary, Aladar Gerevich, Pal Kovacs and Rudolf Karpati, were aging out of the sport. Indeed, Gerevich had been on the Hungarian sabre squad since 1931. Magay, Hamori and Keresztes had been the top contenders to take their spots for the 1960 Olympics. Magay was on the gold-medal winning 1954 World Championship team for Hungary and made the individual finals. Hamori and Keresztes were both on the 1955 team that, likewise, won the team gold. And while the three younger fencers had made the decision to defect from Melbourne, there was no bitterness on the part of the older fencers who remained. Indeed, in later years during an interview for a Hungarian documentary on the country’s domination of sabre fencing, Pal Kovacs stated that if Magay had chosen to return to Hungary, he would have undoubtedly soon become a World Champion. Kovacs had reason to know, as he was a mainstay on a Hungarian squad that, irrespective of what individuals were on any given team, went undefeated from 1925 through 1958 in international competition. If the Hungarian sabremen were in attendance, they won gold.

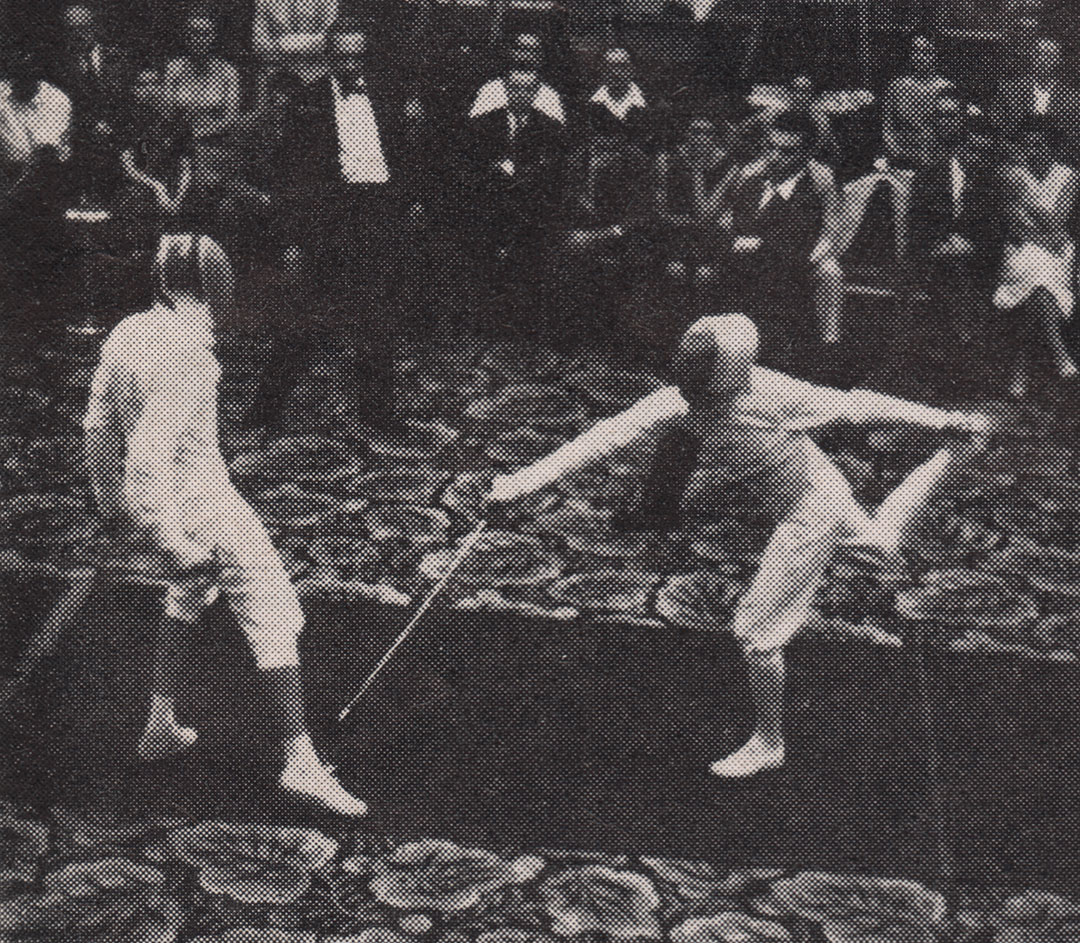

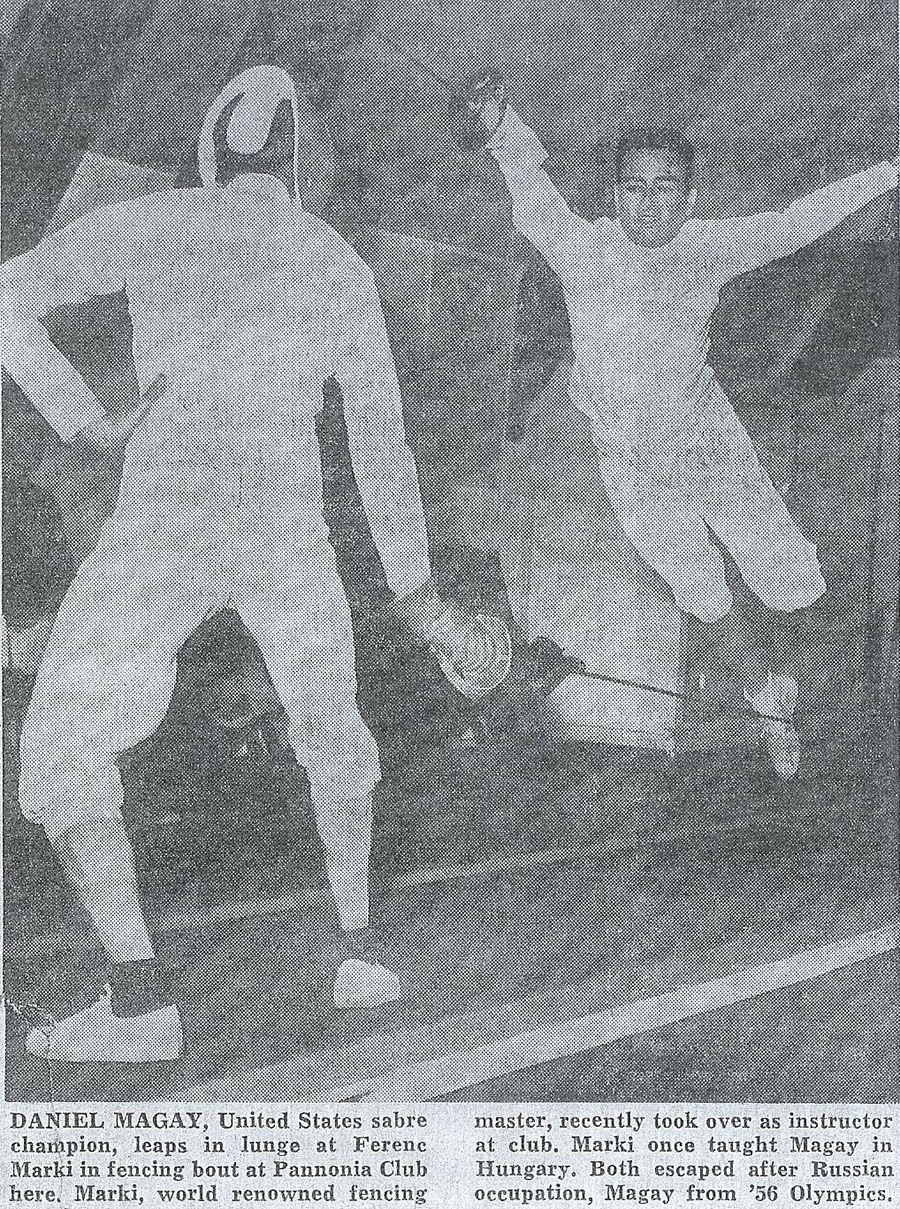

Another photo from the 1958 Nationals shows Keresztes on the left and Magay, mid-flight, on the right.

That was the tradition and expectation that Magay grew up with. In choosing the United States, he knew that the level of training and competition needed to maintain dominance would not be there. The individual coaching was still available, first with Piller and then Ferenc Marki, Magay’s main coach in Hungary, who came to the US in 1961. But the level of competition – and more, the time to focus solely on fencing – was not.

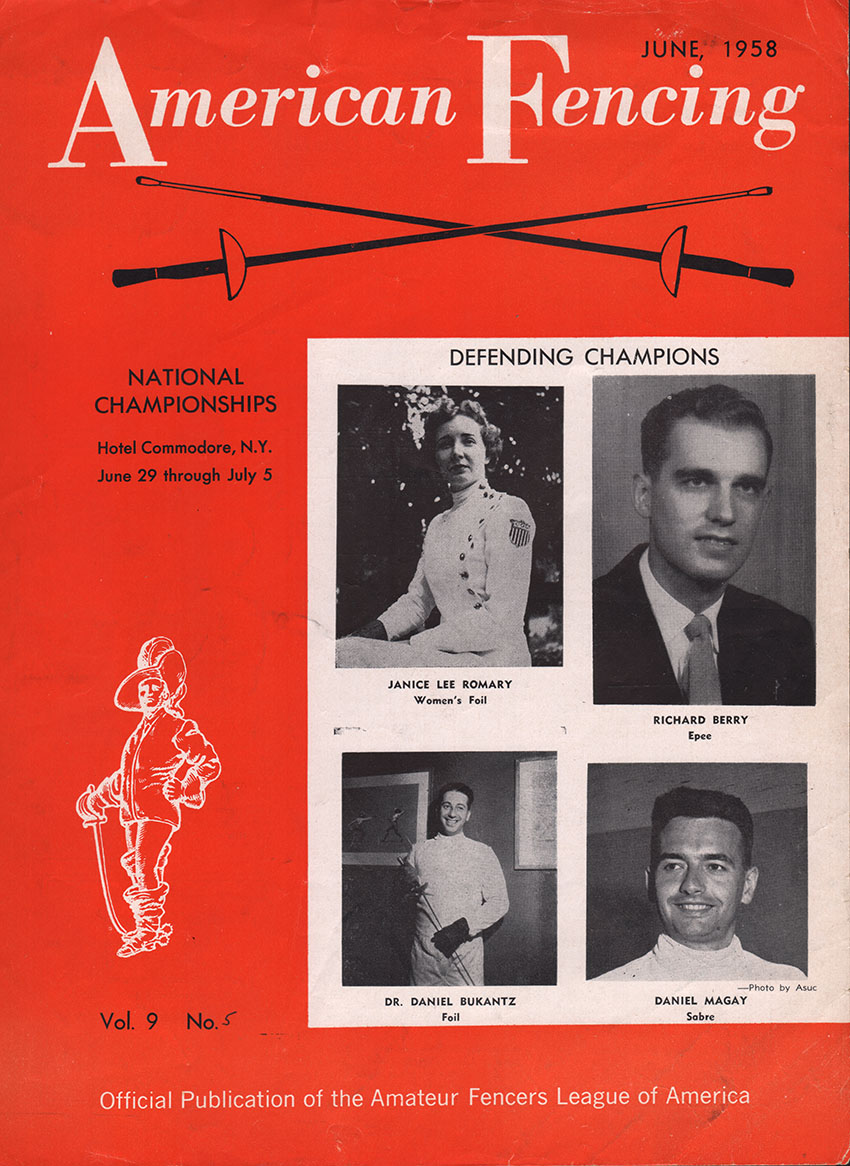

With all that, Magay still became a dominant force in the US. His individual victory in 1958 was nearly a repeat of 1957, ending with a fence-off with Nyilas. 1958 was also the year that saw Philadelphia hosting the World Championships and for the Hungarian contingent of fencers it proved to be a challenging event on many levels. At that time, the top US/Hungarian fencers, Magay, Orley, Hamori and Keresztes, were not yet US citizens. The four of them applied to participate in the World Championships as ‘stateless’ fencers. After a very intense series of meetings and votes, and over the initial objections of the Hungarian delegation, two of the four, Magay and Orley, were accepted as competitors in the individual sabre event. Three days later, after hearing no doubt an earful from Budapest, the Hungarian representatives withdrew their fencers from the individual sabre and epee events, while remaining in the team events. The stateless fencers could not field a team. (Peter Bakonyi, living in Canada, had been accepted into the epee individual event on the same basis as Magay and Orley.) To add a little additional drama, Dan Magay then had an acute attack of appendicitis and was rushed to the hospital. Hamori, the next highest ranked stateless fencer from the 1958 Nationals, was allowed to take Magay’s slot.

Hamori and Orley both proved their right to be there by making it to the semi-finals. In fact, Hamori was on fire early, finishing the first two rounds with just a single defeat. The only American entry to do as well was Robert Blum who reached the finals and finished 8th. Of course, if the Hungarians had entered Karpati, Kovacs and Gerevich, the whole outcome would have been re-written, considering that Hungarian fencers had won 16 of 21 available medals (6 gold, 6 silver, 4 bronze) in the previous 7 years of championships.

1959 was the only Nationals where Dan competed but failed to make the final, bowing in the semi’s. He did not compete at all in 1960. He came storming back in 1961, winning his third Individual title and also helping the Pannonia squad to another gold in Team. In 1962 he finished second to Michael D’Asaro after a fence-off. That was D’Asaro’s only US National individual sabre title. Interestingly, Michael was the first American-born sabre fencer to win the US title since Dick Dyer in 1955. All the rest had gone to Hungarians: Nyilas, Magay, Orley, Hamori – and they won the next three as well, with Hamori capturing a second, and Keresztes and the youngster Orban each winning one.

The lineup in order of placement from the 1961 Nationals. From left: Dan Magay, Eugene Hamori, Helmut Resch (an Austrian Olympic team member), George (Jerzy) Twardokens (a Polish fencer who defected to the US during the 1958 World Championships where he took the individual bronze), Ed Richards, Csaba Pallaghy, Laszlo Pongo, Alex Orban and August Witt.

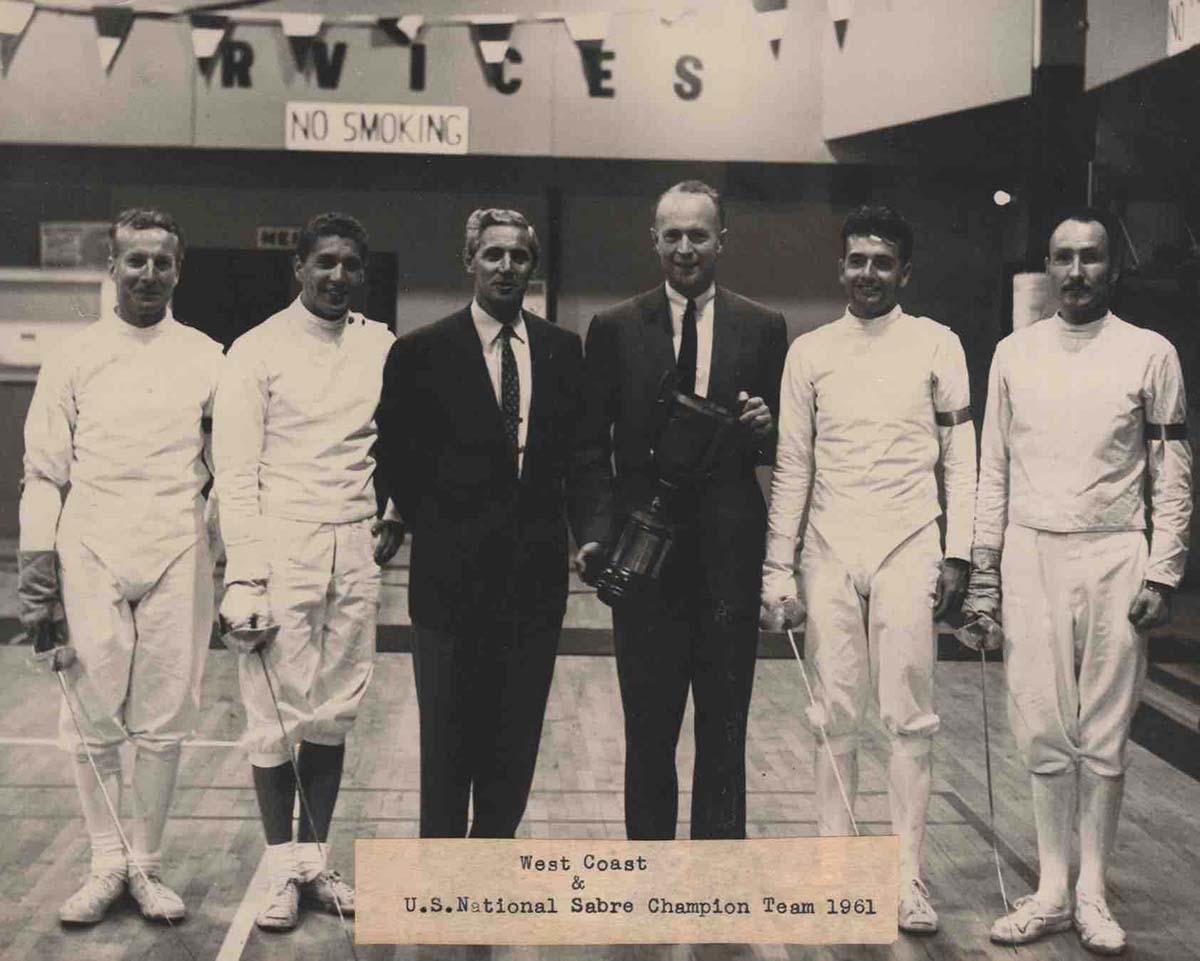

Dan led his Pannonia sabre team to victory at Nationals, as well. From left, Jack Baker, Alex Orban, Julius Palffy-Alpar, William Thiringer (Pannonia club president), Dan Magay, Gerard Biagini. This picture also showed up in last week’s story about Julius Palffy-Alpar!

By 1964 all the Hungarians who defected in 1956 had become American citizens and Olympic rules had been amended to allow an athlete to compete under a second flag. (Rule 41 of the Olympic Charter states that the only stipulation for changing nationalities for Olympic representation is a 3-year period between representing one nation and another. I can’t find when this rule was adopted but it was in between the ’60 and ’64 Olympiads.) Consequently, Magay, Hamori and Keresztes were all eligible to represent the US, along with other new citizens Orley and Orban and several others. The qualifying path to the Olympics had an additional piece as well. National results and an Olympic Trial would both factor in, along with some carryover points from the previous year. However, because rules hadn’t initially been clear (or understood by the fencers), some athletes chose not to compete much in the year prior to the Olympic season. Here’s where it’s interesting: several fencers were granted points for previous years based on their 1964 Nationals result. An estimate of what points they may have won the previous season – when they didn’t compete – were granted. At least, I’m pretty sure that’s how it was all managed. More than 50 years on, it’s all a little blurry. Magay finished Nationals in 8th place. The top four were Keresztes, Hamori, Al Morales and Orley. The Olympic Trials were held just one week after Nationals at the New York World’s Fair. This time, Magay took first place following a fence-off with Robert Blum.

It’s all very confusing as to who got what points for when and how it all added up. The long and short of it was this: Magay was First Alternate, just missing his second Olympic Games. (D’Asaro was Second Alternate.) Former Hungarian Olympic teammates Hamori and Keresztes were both selected, alongside Orley and Morales. The San Francisco Chronicle had an interesting write up about Magay’s situation. It seems he at one point considered legal action to force a reevaluation of the points system and a recount. He wasn’t the only one who thought something might be amiss. In the long run, he dropped the matter. I will say this; I do not believe there was an agenda against Magay or anyone else, although the US was certainly motivated to get the excellent former Hungarians onto the team. In fact, 1964 was the very first time the Olympic team had been selected based entirely on a results-based points system. Maybe there were some issues with it but Dr. Paul Makler, then president of the AFLA and the instigator behind the points system over “selection by committee” which was the previous standard, is a man of great integrity who I respect very highly. If he says they did their best to make it fair – and in an interview he told me exactly that – I believe him.

A news article featuring Ferenc Marki and Dan. Marki was Magay’s coach in Szeged, Hungary and again at Pannonia. Ferenc’s daughter told me that when the family learned that Dan had defected from Melbourne during the Olympic Games, her father said, “Well, that’s it then.” Dan not coming back was the determining factor in his decision to take the family out of Hungary. They went first to Italy, then Brazil. Dan made contact with him in Brazil to ask if he would take over at Pannonia upon the death of George Piller. Marki, followed soon after by his family, moved to San Francisco.

Dan fenced in just one more Nationals, skipping 1965, and in 1966 took second in a 4-way tie. Morales finished the 8-man final 6-1, then Magay, D’Asaro, Orban and Hamori were all knotted at 4-3. Magay took the silver medal on indicators. After that Nationals, Dan felt he had done everything he was capable of in the sport. At age 34, he could only look forward to his skill and stamina deteriorating over time and seeing his results drop accordingly. On the other hand, his newfound love of skiing was something he felt he could only get better at. He stepped away from the sport of fencing from that time on.

It’s noteworthy to me that in Magay’s last National final of 1966, of the men Dan competed against, six of the eight finalists are in the US Fencing Hall of Fame as Fencers. Morales, D’Asaro, Orban, Hamori, Blum and Ed Richards are all HOF fencers. And only one, Alex Orban, won more US individual titles than Dan’s three. Csaba Pallaghy was the other finalist, and while he may not have been a Hall of Fame fencer, which could be debated, he was an extremely capable administrator and worked tirelessly for fencing for decades following his competitive career. But Dan Magay was for many years the top fencer in that crowded field of exceptional competitors, an example of excellence that others aspired to.

Having stepped away entirely from the sport, his memory hasn’t been maintained through interaction with the current generation of fencers. But if we evaluate someone’s right of inclusion in the Hall of Fame based on familiarity, we’ll soon lose track to those who were standard bearers for our sport in years past. I’ll offer up one more quote from a fencing contemporary of Magay’s. Harriet King, four-time Olympian, four-time US National Champion women’s foilist and member of the US Fencing Hall of Fame, emailed me this: “Danny was a graceful stylist and powerful sabreur who was the epitome of a gentleman as well.”

In closing, if I’m not jogging your memory about a great fencer, perhaps I’m creating a new one. Here’s to you, Dan Magay. You were one of the finest fencers of your generation and you’ll get my vote.

Wonderful article! I appreciated learning more about the Hungarian team and especially of my former maestro, Dr. Eugene Hamori.

For many years during my undergraduate studies and afterwards in New Orleans, I was coached by Eugene Hamori in sabre fencing. Eugene was a tireless and most excellent fencing master, always calm, encouraging, and precise. Eugene is much loved by his former fencing students and I always remember him as an amazing athlete and a true gentleman.

Again, glad to read of Eugene’s former years and of his teammates’ stories.

Wayne Gsell

You can see Dr. Hamori in our documentary about George Piller and the Hungarian team called The Last Captain. Available on YouTube and Amazon Prime.

Great article, thanks! I too am a refugee from ’56, arriving with my parents on Christmas day 1956 to Camp Kilmer NJ, where we were processed. I was always proud of Hungarian Sabre Fencing and took up the sport while studying at Cornell. It’s a great sport! During various tournaments I fenced Hamori and Pongo and later met Karpati and Gerevics in Paris while working there. Love the sport and proud of it’s heritage.