Random Stuff

Trying out still more page formatsJust A Standard Page

Nunc et vestibulum velit. Suspendisse euismod eros vel urna bibendum gravida. Phasellus et metus nec dui ornare molestie. In consequat urna sed tincidunt euismod. Praesent non pharetra arcu, at tincidunt sapien. Nullam lobortis ultricies bibendum. Duis elit leo, porta vel nisl in, ullamcorper scelerisque velit. Fusce volutpat purus dolor, vel pulvinar dui porttitor sed. Phasellus ac odio eu quam varius elementum sit amet euismod justo. Sed sit amet blandit ipsum, et consectetur libero. Integer convallis at metus quis molestie. Morbi vitae odio ut ante molestie scelerisque. Aliquam erat volutpat. Vivamus dignissim fringilla semper. Aliquam imperdiet dui a purus pellentesque, non ornare ipsum blandit. Sed imperdiet elit in quam egestas lacinia nec sit amet dui. Cras malesuada tincidunt ante, in luctus tellus hendrerit at. Duis massa mauris, bibendum a mollis a, laoreet quis elit. Nulla pulvinar vestibulum est, in viverra nisi malesuada vel. Nam ut ipsum quis est faucibus mattis eu ut turpis. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Maecenas nunc felis, venenatis in fringilla vel, tempus in turpis. Mauris aliquam dictum dolor at varius. Fusce sed vestibulum metus. Vestibulum dictum ultrices nulla sit amet fermentum.

An Unexpected Addition

In going about my daily Archiving routine, I’m beginning to recognize that small obsessions can take over my focus. Sometimes for days, sometimes longer. Not that they’re out of line with my uber-goals, but they can cause me to veer off topic. Henri J. Uyttenhove is one such obsession. That his history continues to intertwine with that of Harry Maloney, longtime coach at Stanford of fencing, soccer, boxing, rugby and a couple other sports, simply adds to the enjoyment.

Uyttenhove came to this country from his native Belgium to Pasadena, CA, at the behest of a local SoCal amateur, Arthur Jerome Eddy (that’s as much as I know about Eddy) and, interestingly, “…the Belgian master came west, he accompanying Harry Maloney, the Southern California professional champion.” Maloney was 31 when that was written in 1907 in the LA Times and the following year he went north to Stanford. Uyttenhove stayed in SoCal, teaching at his own private salle in Pasadena, the Pasadena Athletic Club, the Los Angeles Athletic Club, the Hollywood Athletic Club and USC. UCLA may have been in there for a brief time, as well.

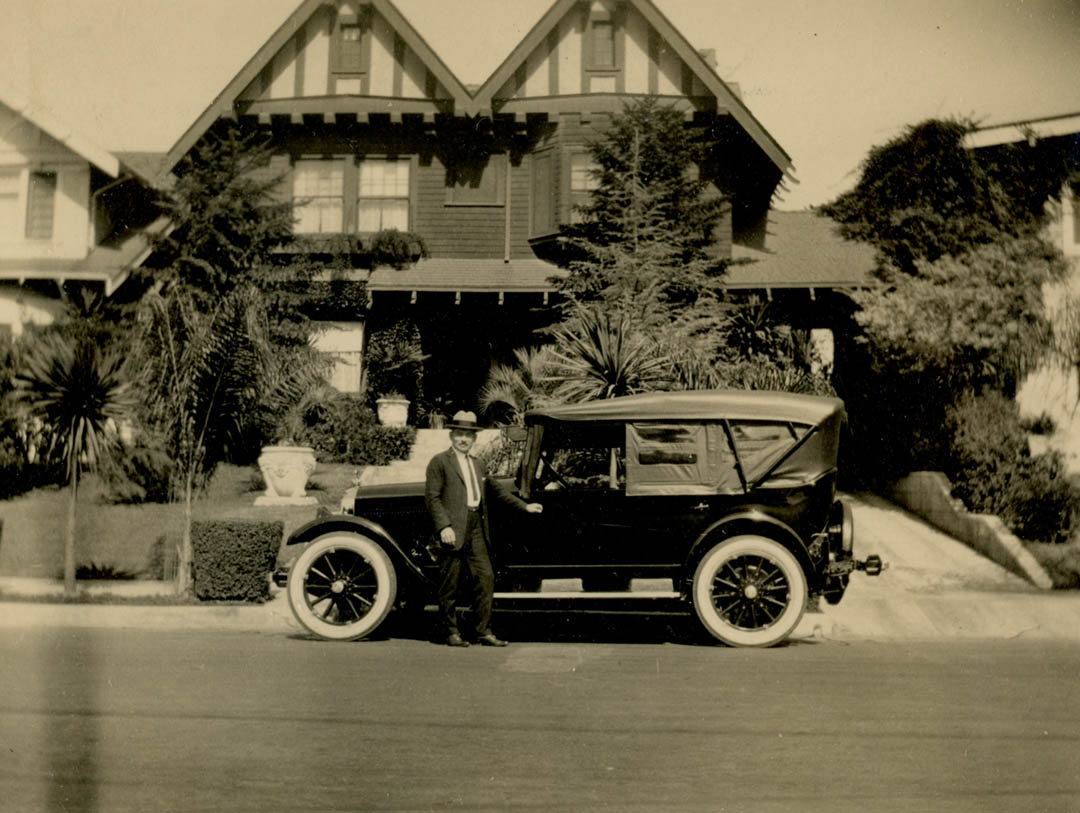

This must be how he got around town so effectively. This photo is from the scrapbook of Muriel Bower and shows Uyttenhove and (presumably) his car. No date or other information, although I wouldn’t be surprised to learn that this house is in Pasadena. That’s the town where Uyttenhove settled when he arrived from Belgium. Anyone able to identify the year on the car?

But here’s where the fun begins. Last year The Archive was the beneficiary of a donation of material from Kevin Murakoshi. He had made an Ebay purchase at some point and came into the possession of a cache of papers and books related to John McKee, long-time fencing master at The Cavaliers club in SoCal. Kevin was kind enough to pass this material on to The Archive. While perusing these papers back in September, I came across a reference to something I’d never heard of before. McKee had put together a list of fencing books in his “Fencer’s Manual”, a book he prepared for publication in 1978. (It wasn’t ever published.) One of the listed books was “Foil Fencing” by H. J. Uyttenhove, along with the date, 1937, and this additional tidbit: “Published by the University of Southern California Athletic Department”. Armed with this bit of information, I spent a good hour Googling that string of information in various ways to see if I could land on a reference to the book. Nothing in Google, nothing on AbeBooks, Amazon, pick a website – I probably looked there. Just nothing.

Figuring I had nothing to lose, I sent an email off to the USC Libraries (note the plural) to see if they had any info. No such luck. They actually checked the WorldCat (which I hadn’t thought of) and didn’t find a reference. That’s likely to mean it wasn’t ever published in a form that would get it a Library of Congress entry, which, while informative, means it’s even less likely that it was put together in such a way as to survive to the present day. The very nice and patient people at USC Libraries did mention that their interconnected library system didn’t have much from the USC Athletic Department and they might well have their own stash of things that hadn’t been entered in their system. Or any system. I tried that recommendation only to hit a dead end. If USC maintains an Athletic Department library where old books might be stashed in a corner and forgotten, I couldn’t find anyone that could point me to a librarian for it, or even a student intern with nothing better to do than peek into some dusty corners. And so, nothing.

My December visit with Muriel Bower revived the memory of trying to find the book. (I’ve been going back through my notes – I haven’t yet transcribed the recording of our conversation – trying to piece together where I ran across another reference to Uyttenhove’s book. But I did.) Armed with a little bit more info, I sent another email off to USC, this time to a Sports Information person. The additional information I’d picked up was that there was an additional subtitle for the book, “A Syllabus for Physical Education”. Again, very pleasant response from USC, but again, never heard of it. With nothing from USC to hold onto, I figured that was the end of it.

Until last week. Early in the week, I got a text from Andy Boyd, the son of Olympian (36 & 48), LAAC fencer and Uyttenhove student Andrew Boyd. (Read about my visit with the Boyds here.) “Mailed you something today. Hope you enjoy it.” A few days later a package arrives. Guess what’s in it?

You can’t make this stuff up.

It really IS the book I’ve been looking for. Seriously, this is so very cool. The book is 42 pages long and the cover has the pencilled number “55” in the upper right hand corner. I’m guessing copy #55 of however many. It’s bound by stapes and the staples are covered very neatly with a binding tape of some kind. The pages themselves may well be typed. There is a hint of ink bleed on the back of each page, the whole thing being single sided, and it doesn’t have that pre-xerox mimeograph look. Still, even if I’m not entirely sure how it was printed, I’m guessing there were once a fair number of copies. Did every fencer get one of these to take home? Or did they collect them at the end of every semester? It’s not surprising either way that Andrew Boyd would have his own copy, as Uyttenhove didn’t train many Olympians. No doubt it was a gift to Boyd. “Hey, I wrote a book! Here’s a copy for you. Ok, back to work…”

The book, like many fencing books, spells out the pertinent terms that need to be defined for the students and lays out the lesson plans for a course of study in 10 sessions. The final lesson, learning the Grand Salute, has a nicely detailed description of that now seldom seen bit of performance art. What I was hoping for during my search for this volume was that it would have some amount of introduction or storytelling that would give me a sense of Uyttenhove’s character or thinking. That’s one of the great benefits of Aldo Nadi’s “On Fencing”. You get a fair sense of the author through his use of language, as he writes enough material that isn’t “…put your hand here, hit the target there…” so the reader can get a little way inside Nadi’s head. Of that kind of writing, this book is sadly lacking – at least, I’d hoped for more. Since, as the title states, it was written as a syllabus for a college course of instruction, I can’t be terribly surprised. Still, what he has written in the Introduction does provide a bit of glimpse into his motivations and his personality.

This is the opening paragraph of the Introduction. He follows up with a brief note that fencing in the United States is becoming more popular in colleges and universities, as well as mentioning that in the East, high schools are also beginning to offer fencing as a course of instruction. As in, “Hey Westerners! More fencing sooner!” 83 years later, we’re finally getting kids into fencing, even as the University system continues to shutter programs. Why can’t we have both? A topic for another time, I suppose.

The introduction continues with 9 objectives for the student to accomplish over the course of instruction. These cover two pages, so here’s the first five reasons:

“…a perfect co-ordination of mind and body.” Clearly, I’ve been doing it wrong these past 40 years. Ah well.

I love these. I particularly like #2: “One acquires a knowledge of the art of fencing through instruction, and in a bout, this knowledge is applied in a contest of skill and ability.” Such a simple description in a single sentence, yet it encapsulates the experience so precisely. It works whether your instruction is sufficient, or if your ability is limited. Whatever your base state, that’s it in a nutshell. I also like this: “Fencing is a distinctively individual sport, and thus each fencer shoulders his own responsibility.” I played only team sports growing up. Fencing was my first individual sport and I started at 18. There was, for me, a surprising learning curve in adjusting to the lack of assistance from teammates during a fencing bout. And really, is there any other endeavor that I can as readily point to as having challenged me to ‘use my native capacities to the maximum’? Ok, well, there’s probably a few things other than fencing. But it’s definitely on the list.

Here are the last four of the nine reasons:

He nicely brings in the notion that the sport is fit for both men and women, even if the idea that it is ‘exempt from the danger of bodily harm’ may be stretching the truth, particularly in the 1930s when there was more than one incident of bodily harm on report related to the sport. It isn’t a regular feature of the sport though, and even less so today, so I’ll let it go.

The last one really has the most powerful message for me, and it certainly calls to mind our present day. It’s worth repeating:

Fencing encourages a willingness to participate in individual and group activities, imparts a tolerance toward others regardless of race, and stimulates a high regard for the religious and political beliefs of all people.

Henri J. Uyttenhove, ladies and gentlemen. That sentiment, more than anything, I think provides an insight into the nature of the man we’re looking at. Tolerance, and a high regard for others. Those are two ideas I can embrace.

After these introductory pages, it proceeds to the actual day-to-day instruction for a beginning foil class. He writes in a very concise style and describes things quite nicely. You could probably use the same instruction today over a ten week intro course and not have to do much revision for today’s fencing. He knew his material – after completing his fencing master’s certificate in Belgium, he ran the military’s fencing master program for a few years prior to coming to California. So he was well versed in pedagogy. And, like Nadi, he’s perfectly comfortable writing in English.

There is another Uyttenhove story lingering in my to-do box, but it will have to wait for another time. But this story today, complete with surprising coincidence and insight into a man I could never have met, will be as far as we go today. I’ll end with this photo with Uyttenhove and his fencers from the University of Southern California, circa 1938.

Historical Holiday

Driving around Southern California may not seem like much of a Holiday, especially when traveling alone, but a recent weekend outmatched all my expectations. The plan was to make four different stops in hopes of collecting fencing history. All four planned stops were made, history was collected, old friends were visited and lobster toast was experienced on Highway 1 in Malibu. Really, it could not have gone better.

I’ll begin at the beginning. After a Facebook back and forth, I had a nice phone call with Jo Redmon, the retired long-time coach at Cal State Long Beach who, among other things, told me she had left some collegiate fencing records in SoCal upon her retirement to Arizona. They’d been left with Eric Holmgren at Gryphon Fencing in Placentia. Easy enough to track down and sure thing, Eric said there were several boxes, no one was doing anything with them and if I thought I could make heads or tails of them, I was welcome. The only catch was they were too heavy to ship in any reasonable fashion, so I’d need to come down and pick them up. Now, I live in NorCal today, but I grew up and spent a good part of my animation career working in SoCal, so a trip south is nothing terribly out of the ordinary. Although I usually take such excursions with my family and include stops at Disneyland and the homes of friends spread out all over the Inland Empire. Still, something to put on the docket for the new year.

Then I had another phone call that changed the pace. A month or so back, I got a mailing address from Buzz Hurst for one Muriel (Caulkins) (Bower) Taitt. Earlier in the year I’d been trying to help Vinnie Bradford with some references for a talk she was presenting at a TEDx event. (You can see it here.) Vinnie had been trying to get Muriel by phone with no luck. I figured since I had Muriel’s mailing address, I’d send a message that way and see if I had any luck. I typed up a nice letter, enclosed my Archive’s tri-fold flyer with a business card and off it went via USPS. If you don’t know (and I’ll use the name more recognizable to the fencing community) who Muriel Bower is, she is the retired former coach of Cal State Northridge and she is 98 years old. Less than a week after sending my letter, my phone rings and it’s Muriel. She’s a little hard of hearing (ninety eight) but she’s sharp as can be. We talked about my Archive and that I’d like to come interview her if she was amenable. She invited me to come down whenever I could and she’d be happy to talk. And, she said, “I’ve got a scrapbook.”

You may or may not have gleaned this from reading my posts on this website (assuming you’ve been here before) but the word “scrapbook” is one that pushes up my heart rate into the “Warning!” range. It’s possible such a reaction stems from the initial material that helped me formulate the idea for creating the Archive, namely Charlie Selberg’s scrapbooks. Still, every scrapbook is different in form and content. Some are easy to copy, some are impossible, some are in great shape and some are falling apart. But “scrapbook” still means one important thing: additions to the historic record, if I can somehow copy the info.

That’s all an aside. After I got off the phone with Muriel, I wandered into the kitchen where my wife was making tea and said, “I think I need to drive to LA.” I explained about both the boxes I needed to pick up, and Muriel, the scrapbook and 98 years old, then started going through my calendar. For some reason, even knowing it’s likely to mean an overall increase in the mass of material that currently keeps us from parking cars in our garage, my wife didn’t bat an eye as I made my plans to disappear for a few days. In addition to these two items, I had also heard from Jamie Douraghy that Heizaburo Okawa had put some more swords in his hands to send my way, since I’d already been gifted a very large collection of Okawa/Torao Mori/Joseph Vince material that had languished in Heizaburo’s backyard for quite awhile. On top of that, I’d long wanted to get to Thousand Oaks and see Phil Hareff at Conejo Fencing Club, which was started by 1928 and 1932 Olympian Duris de Jong. I knew Phil had some Duris memorabilia and I hoped to see that, as well.

I left the house on the morning of 12 Dec with four stops lined up: Gryphon in Placentia, Muriel in Palm Desert, Jamie on the Westside and Conejo in Thousand Oaks.

Ran into a little bit of tule fog on the I-5, but nothing to slow down the traffic.

Cory Price, one of the Gryphon coaches, greeted me at the door when I arrived at around 5pm. Eric was out at their other location and another coach, Heik Hambarzumian, an old friend, wasn’t in yet. But the boxes were all there, five of them, ready to roll. As we did a cursory look-over, Cory mentioned there were some other items I should take. Up he went into their storage loft and came down with seven framed pictures and an envelope with a bunch of loose prints of various sizes. Sometime back, they had all been dropped off by someone, probably a relation of one of the subjects in the photos, after the death of the person in the pictures. They apparently reasoned, quite correctly in my opinion, that fencing pictures should go to a fencing club. There are certainly worse alternatives. But the guys at Gryphon didn’t know the person in the photos and put them all in storage.

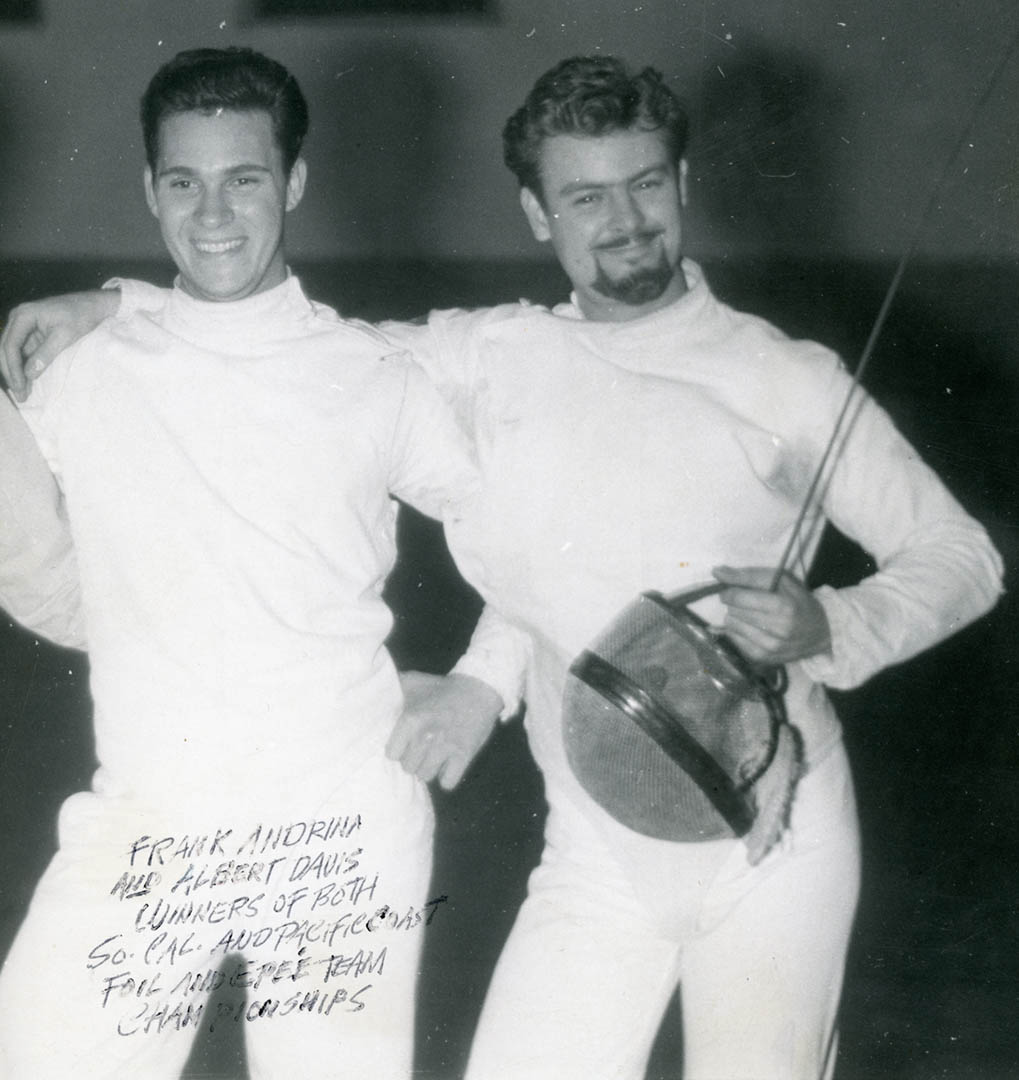

The fencer who was the consistent subject of the framed images was Frank Andrina, a fencer at the Faulkner School of Fencing. In fact, each of the framed pictures had a brass plaque on the bottom of the frame reading, “Property of FSF”. Best guess, when Ralph Faulkner passed away, those who could took possession of things that had once formed the club decor and had meaning to them. Whether Frank himself was able to get ahold of these, or someone else sent them his way, I’ll likely never know. But each of the photos, both framed and unframed, have Frank in them. That’s got to be more than mere coincidence as to who had them prior to their landing at Gryphon.

Frank Andrina on the right with Albert Davis. The caption reads, “Winners of both So. Cal. and Pacific Coast Foil and Epee Team Championships.” A search through American Fencing Magazine would suggest the year as 1958 when Davis was on the winning epee team, Group 2, and Andrina was on the winning foil team, also Group 2. Near as I can tell, Group 1 was the Open division and Group 2 was the Intermediate division.

By far, the most interesting thing about the framed photos are the captions. They extoll the capability of Frank Andrina, the fencer. Indeed, they praise him to the skies. Here’s a quote from one of the pictures, attributed to Joseph Vince: “Mr. Andrina has performed the finest foil fencing I have ever seen. He handles a foil like a musical instrument.” And that’s not even the best one. That honor goes to a quote attributed to one “G. H. Zoll, former Italian and Olympic fencing coach”. Anybody heard of him? His quote reads, “Mr. Andrina has the fastest counter of quarte I’ve ever seen, much faster than Christian D’Orola [sic] of France, and also the current Olympic foil champion, who is also left-handed, whom tonight Mr. Andrina could have easily defeated. Frank is faster and more aggressive.” To be clear, Christian D’Oriola of France was, and I’ll just count the Individual Gold Medals, 4-time World Champion and 2-time Olympic Champion and was ‘easily defeated’ by exactly no one. I have no doubt that consummate showman and fencing promotionalist Ralph Faulkner typed up the broadly exaggerated captions himself, poor spelling and all.

This photo is undated and has nothing written on it to ID anyone, same as the others in the envelope of loose prints, of which there are about 30. I’m pretty certain from comparing the knickers and short socks of the fencer on the right to someone identified in one of the captioned pictures that Frank (the lefty) is here facing long-time SoCal fencing stalwart Joseph Lampl. I’m curious to track down more about Frank. The only person a Google search turns up by that name worked for decades as an animator for the likes of Disney and Hanna-Barbera, among many others. Gotta be the same guy.

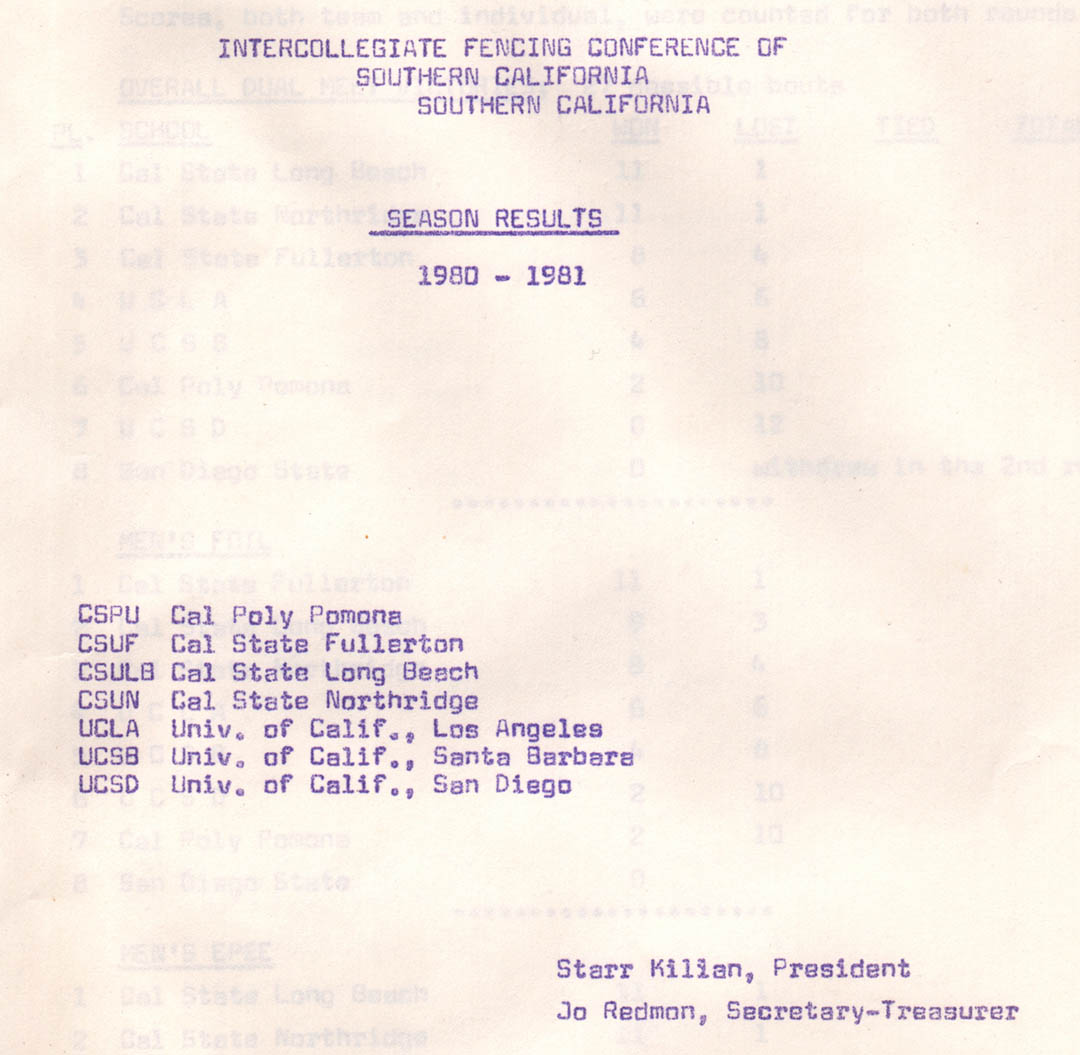

As interesting as the Frank Andrina haul is, it was not the bulk of my pickup. The boxes I had discussed with Jo Redmon were stuffed with the records of the Intercollegiate Fencing Conference of Southern California going back to 1967 and I loaded them all into my car with Cory’s help. I’ve only just scratched the surface of what’s included, but a random pull from the front file of one of the boxes revealed a bundle of papers from my era of collegiate competition, although I was ensconced in NorCal.

The cover sheet for the full results of the season down to who won exactly how many bouts and the results of every single dual meet. I found it particularly interesting because I was the stunt-student during Starr Kilian’s Prevost exam at San Jose State. The examiners were Charlie Selberg, John McDougall and Ferenc Marki, which I thought was a bit suspect, as Starr had gone to UCSC and was Charlie’s student. I don’t actually know if Starr passed the exam or not. He was teaching at Cal Poly Pomona.

Here are the final results for the season. The 80-81 season was my last competitive year for SJSU, so many of these names are super familiar. I had knock-down, drag-out bouts with both Frank Fox and Ray Bautista, had fenced against Joe Metcalfe and Larry Riggins the previous year when I was on the epee team, Ruth Botengan was always a tough bout at mixed opens or in later years at Westside Fencing Center and Larry Dunn may be reading this right now! So there that is. Lots more to discover in these boxes.

Great start to my trip so far. Day two began with a beautiful sunrise over the San Jacinto Mountains, as I did my overnight in Palm Desert.

A little dusting of snow on the peak of Mt. San Jacinto.

Muriel met me at the door of her apartment inside a retirement community – a really nice one, by the way – and invited me inside. We sat at the round table in her sitting room and she had her scrapbook out on the table. It was a black 3-ring binder and most all the photos and clippings were inserted into protective sleeves. For the next two hours, we went page by page through the book, each picture or news clipping bringing up some memory for her that she was able to turn into a story for me. Thanks to all the research I’ve been doing, she didn’t need to explain to me who people were as just about everyone we spoke about was familiar to me. The exceptions were a few teammates from her days at the Los Angeles Athletic Club. I’d read a caption and mention a name, usually of one of the young ladies depicted in a photo with Muriel, and she would comment, “Well, she wasn’t really very good.” And that, honestly, is why I’d never heard their name before. Lots of students filter through a club over time and the LAAC in the ’30s and ’40s was no exception.

Fencing at the LAAC in 1938. Muriel has her back to the camera and is the one lunging closest to the camera. Teaching on the left is DeLoss McGraw, Team Captain, student and Coach at USC. Teaching in the back, left handed, is Henri Uyttenhove, the long-time LAAC coach and Muriel’s first fencing master.

Muriel began fencing at the LAAC at the age of 13. Her uncle had a membership and that’s how she was able to get in and start swim lessons, which was her other strong sport. She only began fencing after becoming fascinated with watching the fencers after her swimming was done. She watched everyone taking a lesson, took note of the tips Uyttenhove would dispense and then practice the moves in front of a mirror at home. Uyttenhove had noticed her and approached Muriel’s parents about her trying out fencing. In the first lesson, Uyttenhove was surprised to learn that Muriel had already been working on her form and the hand positions – to positive effect – and took her on as a protégé. This all took place in 1933, a time when fencing great Helene Mayer would come to the LAAC from where she was studying at Scripps College in Claremont to take lessons from Uyttenhove. Muriel idolized Helene. “She was so beautiful and strong. Powerful.” Helene would fence with the youngster and they became good friends. Muriel shared a letter she received from Helene in 1942 discussing the possibility of Helene, Muriel and Moreene Fitz forming a composite team for the upcoming Nationals in New York. Muriel had just won the Pacific Coast Championships, Moreene was a National finalist and Helene was, well, Helene. They may not have been allowed, under the rules in place at the time, to form a cross-division composite team. They didn’t win. I only have the record of the team that finished in 1st place that year. My suspicion is they didn’t compete in the team event.

This news photo is from 1938 or 1939, advertising the California Girls who are off to Nationals. L-R: Muriel Caulkins/LAAC, Helene Mayer/San Francisco, Cornelia Sanger/LAAC.

Muriel mentioned, and why wouldn’t you, that she was one of only two women to ever defeat Helene Mayer in a tournament in the US. It was in an early round and so didn’t figure in the final decision, but I’ve no other record of Helene ever dropping a bout in the US, except her very last match in competition where her opponent’s husband was allowed to officiate the bout. Imagine the hilarity that ensued.

Henri Uyttenhove of the LAAC and Muriel’s first coach is someone I don’t know nearly enough about and I’ve actually gleaned quite a lot. He arrived in Pasadena in 1909 and taught at the Pasadena Athletic Club. He taught at the LAAC and USC. He was the first credited swordfight choreographer in Hollywood and taught Douglas Fairbanks, Sr. He coached two-time Olympian Andrew Boyd, Fred Linkmeyer, Ralph Faulkner, gave Olympic champion Helene Mayer lessons when she was in town, and coached Muriel to a near Olympic berth.

Muriel in 1950, just after winning the Pacific Coast Championships.

Leading up to Olympic team selection in 1952, the California ladies dominated. Between four women, they finished 1-2-3 at Nationals in 1950, ’51 and ’52: Jan York, Maxine Mitchell, Polly Craus and Muriel Bower. (Muriel had married by this point.) The big showdown would be the 1952 Nationals, with the top 3 finishers likely being the ones selected for the team. Just prior to Nationals, Muriel was in a car wreck, taking a big blow to the back of the head that caused searing pain if she moved too fast or was under stress – just exactly the prognosis you don’t want to hear prior to an athletic event with the Olympics at stake. Her doctor forbid her from competing, telling her that she was done with that for good. Sometime later Muriel proved him right by getting a flash of searing pain and passing out on the strip during her first and only attempt at trying to get back to competition.

Henri Uyttenhove surrounded by the women fencers from the LAAC. Muriel is immediately to the left of Uyttenhove.

The other strong influence on Muriel at the LAAC was the successor to Uyttenhove’s time as fencing master, Jean Heremans who, like Uyttenhove, received his fencing masters credentials in Belgium. He also followed Uyttenhove into Hollywood work and is the fight choreographer responsible for one of the greatest, most outlandish and entertaining screen fights ever. Of course I mean the theater fight in Scaramouche.

Heremans was so good he could coach four ladies at once! Muriel is second from left in the red shirt. Tall and handsome, Heremans was also an excellent coach and was the one responsible for prepping Muriel for her Olympic run.

Another effect of her work with Heremans was Muriel’s introduction to coaching. Heremans was coaching at the LAAC, USC, in Hollywood and at a private club, and was running himself ragged. At a certain point, he suggested to Muriel that she take on some work as a teacher, since she could no longer compete. She would at least still be around the sport. She jumped at the chance and in between teaching classes, Heremans instructed her on the finer points of fencing instruction. Those skills helped prepare her for her first collegiate coaching job at USC. Teaching there for several years, she then took a job at Valley State College, later California State University Northridge. If California does anything well, it’s giving long names to colleges. She was one of the first, if not the very first, female fencing masters in the US. She also co-authored an excellent book with Torao Mori, “Foil Fencing”, which has been reprinted in at least 8 editions, and she was also the first female coach to host the NCAA Championships.

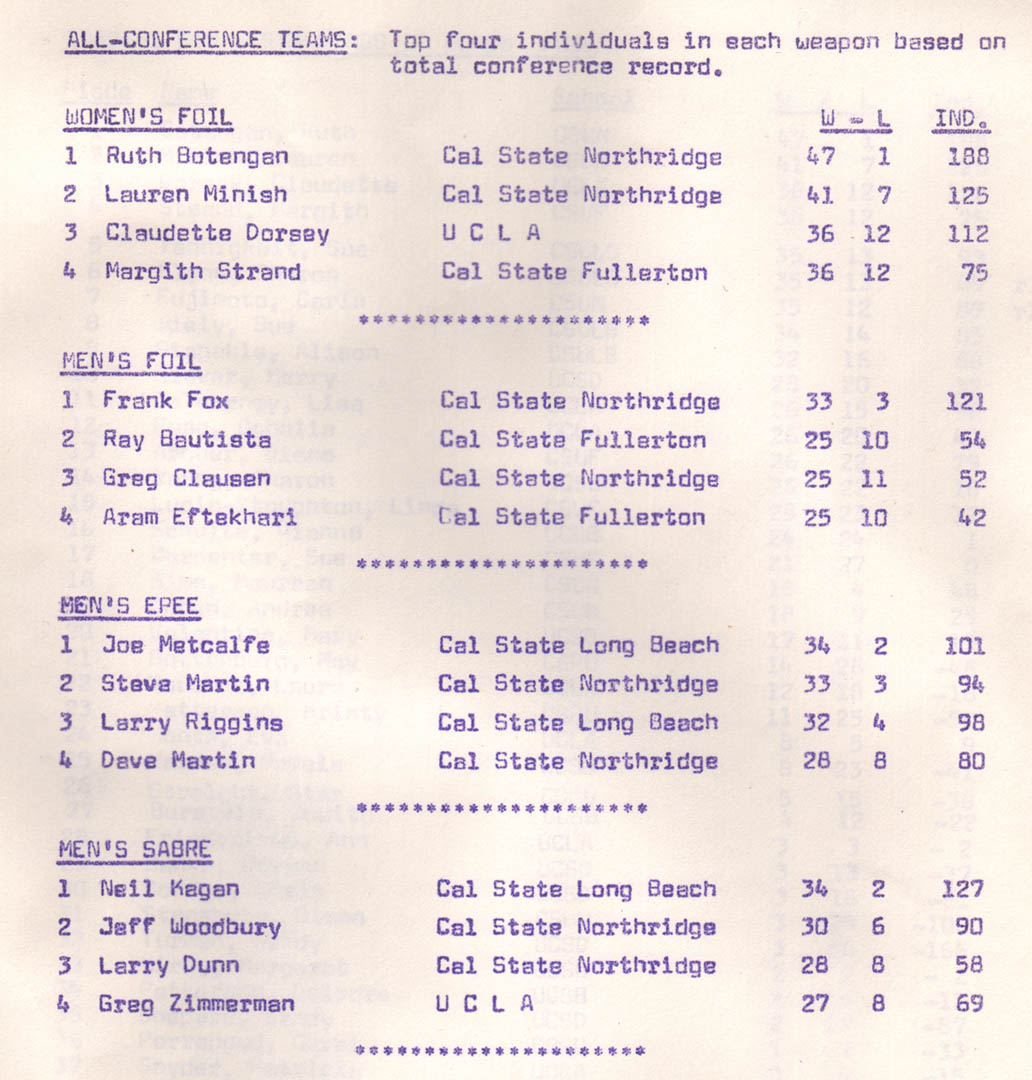

An article from 1967 valiantly trying to make fencing scoring machines sound like some sort of magical device.

To say that I enjoyed my visit with Muriel would be a huge understatement. We talked about everyone in her scrapbook and a few others I brought up for two hours, then she was patient enough to allow me to spend another hour scanning every page in that scrapbook. It’s a treasure trove of material. I finally got out of her hair at about 12:30 in the afternoon to brave the traffic toward Hermosa Beach where I spent the night with friends.

Two stops down, two to go. After waking up to the sounds of the waves crashing on the shore at Hermosa and a wonderful morning with storytelling, coffee and sausages, I headed to the West Side (LA vernacular for Santa Monica and surrounds) to meet up with Jamie Douraghy. For those of you playing Archive Donation Bingo, Jamie is responsible for landing the Heizaburo Okawa collection with the Archive. A couple of years back, I got a call from Jamie – he knew I had created the Archive – and he said that due to some remodeling and a leaky old shed, some fencing memorabilia had been water damaged, Heizaburo had it in a dumpster and did I want any of it? “No,” I answered. “I want ALL of it.” Archive and Filmmaking partner, and invaluable friend, Greg Lynch drove over to Heizaburo’s house (I was 350 miles away) to fill his SUV with stuff from the careers of three hugely important fencing masters; Heizaburo Okawa, Torao Mori and Joseph Vince. Greg and I met at Kettleman City, swapped it from his SUV to mine, and into the Archive it all went. Well, Heizaburo had run across a few more swords, trophy-type awards, that he didn’t need any longer and if I wanted to add them to my collection, I was welcome. Jamie had let me know about them a month or so ago, and we discussed how to get them to me. Hence the trip to the Westside and a visit to Jamie’s garage. To top it off, Jamie dropped a couple of things of his own on me, as well. Bonus material achieved! I haven’t photographed the swords (yet) so I don’t have any relevant photos to add to this part of the story. Instead, here’s the Monorail!

On my initial day of driving, I stopped in at Downtown Disney for a quick bite before going to Gryphon, one town over from Anaheim. Wanting to get through the bulk of the LA basin traffic and into Orange County before 5pm, I blasted through town and arrived in Anaheim with a few hours to kill before Gryphon opened. So what the heck, I cooled my heels with Mickey and watched the Monorail whoosh overhead. Trader Sam’s was too crowded (at 3pm on a Thursday?) to grab a tiki-themed beverage.

My last collection stop was up in Thousand Oaks on the far side of the Santa Monica Mountains from Jamie’s house. I could have taken a selection of congested freeways to get there, but what fun is that when you can instead drive along the beach in Malibu? So north on Highway 1 after a slow cruise through Santa Monica’s beachside shopping/strolling scene I went, hitting the Malibu-bound traffic just as I started to think about lunch. I’m not terribly Malibu savvy, so after passing a few places that I too late thought looked good, I just steeled myself to pull into the next likely looking joint. Ended up sitting at the counter of a nice-but-casual little diner-y kind of place with a French head chef and a sous chef who was sautéeing a wide array of mushrooms the whole time I was there. Like any up-to-current tastes place, they had avocado toast prominently featured on the menu, but as much as I like avocado I had to pass on that choice in favor of the lobster toast with a béchamel sauce (French chef) and a side of greens, and it was delicious. From there, on through Malibu Canyon to Thousand Oaks and the Conejo Fencing Club.

Duris de Jong in 1925, a young fencing champion. The original Dutch spelling of his first name was “Doris”, but when he came to the US he changed it to “Duris”.

I’ve traded emails off and on over the last couple of years with Conejo’s Phillip Hareff about the founder of the club, Duris de Jong, and was very happy I had time on my schedule to stop and see what Duris had left with him. Duris de Jong competed for the Netherlands at the 1928 and 1932 Olympic Games. He had moved to the US after the ’28 Games and when the Netherlands opted not to send their fencers to LA in ’32, Duris applied to his National Governing Body for permission to compete. Since it wouldn’t cost them anything, they said, “Sure!” He taught for many years in SoCal, won many tournaments, and was a fixture at the Hollywood Athletic Club as Fencing Master there until the 60s or 70s. By 1976 he and his wife had moved to Thousand Oaks and he opened up Conejo Fencing at a recreation hall in a public park.

The elder statesman of Conejo stands in front of a number of students. Phil stands far left holding what looks like a cake. Duris passed away in 1990 at the age of 88.

I didn’t know what to expect in the way of what memorabilia Duris had left with his successor, Phil, but having very little other information about him made a visit to Conejo something I’d starred in my head some time ago. They’ve got a nice space, had three or four electric strips going and a very friendly group of folks trading touches like fencers will do. Phil introduced me to the group, I gave my short version of what the Archive is all about and why I was visiting, going so far as to put in a plug for my feature documentary, The Last Captain about George Piller. (Look, I’ve done it again!) Piller actually knew and liked Duris – the ’28 and ’32 Olympics were a shared experience for them – so I wasn’t straying too far off topic. (Piller and de Jong met in Foil Team in ’28, Piller winning 5-3, and in Sabre Individual in ’32, Piller, the eventual Gold medalist, winning 5-2.)

A 1937 publicity photo featuring Ed Carfagno on the left and Duris on the right. Ed was a national finalist several times, taking 2nd in foil in 1939, and also a Hollywood art director and production designer, winner of three Academy Awards. This photo was taken during the David O. Selznick “Prisoner of Zenda” Trophy competition. Where’s that trophy? And who won?

As part of my spiel about the Archive, I mentioned some of the memorabilia that I’ve collected from various SoCal personalities like Ralph Faulkner, and mentioned things that have gotten lost through the years, like the large bronze sculpture of Faulkner that graced the Faulkner School of Fencing and the Westside Fencing Center. One of Phil’s fencers said, “I know who has that!” Well, it’s little moments like this that really get me amped up. The Faulkner bust?! In a known location? That’s big news in my world. So big shout out to David Varon for clueing me in with the information he had about the whereabouts of the sculpture. I’ve reached out. I hope I can photograph it someday.

This is the only photo I have of the Faulkner bust. Andy Shaw may have more, as it graced the Westside Fencing Center for many years.

Phil showed me a couple of photos they had tucked around the club space. Not a ton; it’s a shared space through Parks & Rec, so you wouldn’t want to risk valuable items. He then packed up his gear and I followed him over to his home, where he kept the bulk of the fencing memorabilia gifted to him by Duris. And, while not a scrapbook, he has a really nice set of trophies on a fireplace ledge and a few terrific photos of Duris as a young man. Some of the trophies were pretty significant. There’s a Nedo Nadi trophy, a full-body figure that’s sort-of Nadi-ish. Beautiful thing, actually. Most of the trophies are cups, tall and small, from the 1930s.

Trophies and plaques won by Duris de Jong. Love that LAAC patch and I’ve no idea what the patch is with the blue and red stars. The “H” patch might be for the Hollywood Athletic Club, but that’s just a guess.

He also had the fencing bag of Attila Keresztes from the 1964 Olympics. Keresztes was one of the three members of the six-man Hungarian sabre team who defected with Piller from the 1956 Melbourne Olympics and settled in the US.

He lived in the LA area in the late 50’s into the mid-60’s and in 1964, with ’56 teammate Jeno Hamori and also Al Morales and Tom Orley, was selected for the US sabre team for ’64/Tokyo. The story is this: after returning from Tokyo, he visited his good friends the de Jong’s, leaving his fencing bag, saying, “I’ll pick it up another time.” But he never did. One of the sabres is an example of the hand-made guards crafted by Lajos Csiszar and includes an engraving inside the guard.

Google Translate says (more or less), “To Attila, with love from your Master. Csiszar S. Lajos, 1964.”

After scanning, photographing and swapping fun fencing stories with Phil, I packed up and headed off to Sherman Oaks and another overnight with friends before heading toward home on Sunday morning. As always after a visit that includes any scanning of images, I was panicked until I got the pictures backed up on my home computer and hard drives. Plowing through all the images from Muriel, the photos of Duris from Phil, the swords, and the records I collected, I’m so glad I made the time to get down to the Southland to do a mad dash around the state, not to mention thankful that my wife casually chalked it up to just another of the odd life choices I seem to make. According to Google Maps, it was over 18 hours of driving time covering more than 1,000 miles. No wonder I was tuckered out when I finally got home.

That’s a wrap for the stories of 2019! ‘Tis the holiday season, so I’ll be taking a break until 2020. It’s been an amazing year for the West Coast Fencing Archive. The website got a great re-design that launched in March, new collections have come my way, discoveries have been made and projects continue to line up. Here’s hoping the New Year brings peace to the world and joy to you and yours. My holiday wish is simply for more space in my garage. Cheers!

Catalogs!

Every now and again I rummage through material I’ve collected for this Archive and get reminded of people and things that I haven’t turned my full attention to. Just before Thanksgiving, it was the files in my office related to the Joseph Vince Fencing Equipment Company. In the midst of the file I was going through were a large number of equipment catalogs. I thought I’d share a few.

The ’69-’70 catalog for the Joseph Vince Company. The circle logo next to Mr. Vince’s name is the symbol of Salle Mori. Torao Mori bought out Joe Vince when the venerable Hungarian decided to retire. Mori took over his Beverly Hills salle and also his equipment company, but kept the Vince name on the equipment company. Mori passed away in January of 1969, but his family continued to operate the equipment company for many years. When Heizaburo Okawa donated a large cache of material to the Archive, included were the files of the equipment business going back to the 1950’s.

Joseph Vince was responsible for assisting a fledgling equipment manufacturer in Japan get their products into the American market. Whether he approached them or they approached him I’m not sure, but I’ve found in his files manufacturing drawings detailing the exact specifications for foil guards and some other pieces of equipment. And I’m not sure if Vince was the sole US distributor for this new player, but I know when I was fencing in the late 70’s I would often run across this name on this or that piece of equipment. I think I still have an old bag of theirs, actually.

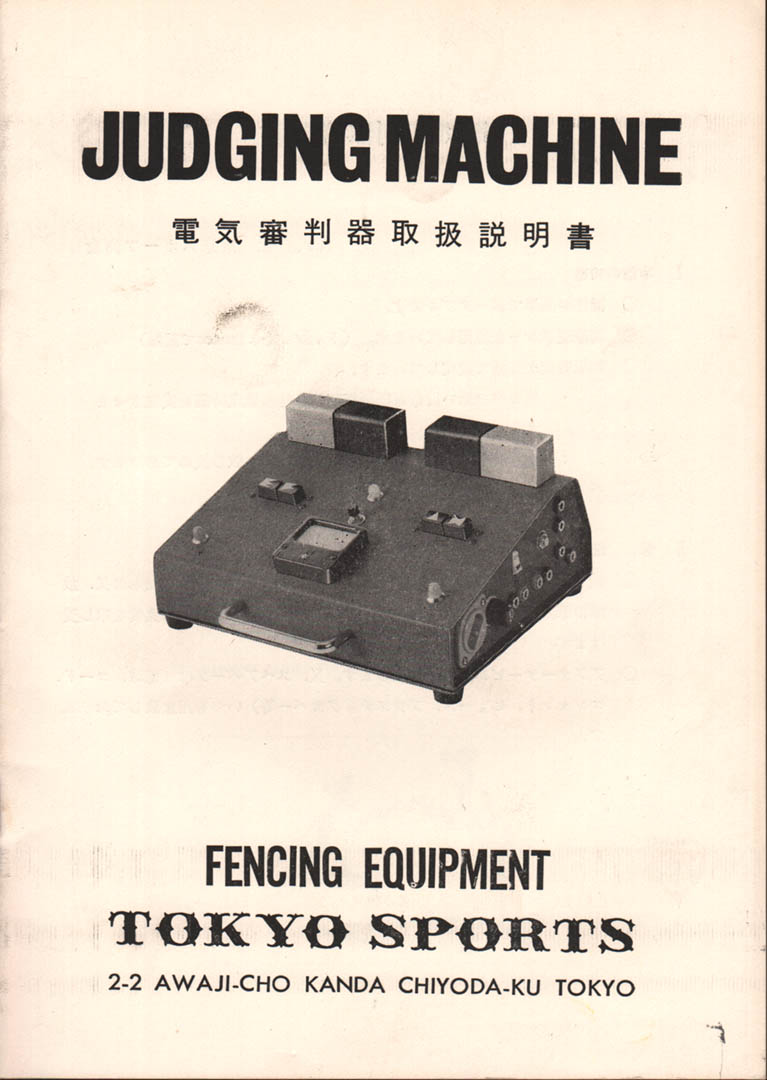

Tokyo Sports went big into fencing equipment, producing everything from weapons, parts, body cords, masks, clothing and scoring equipment, as you can see from this cover. This catalog is all about their line of scoring equipment.

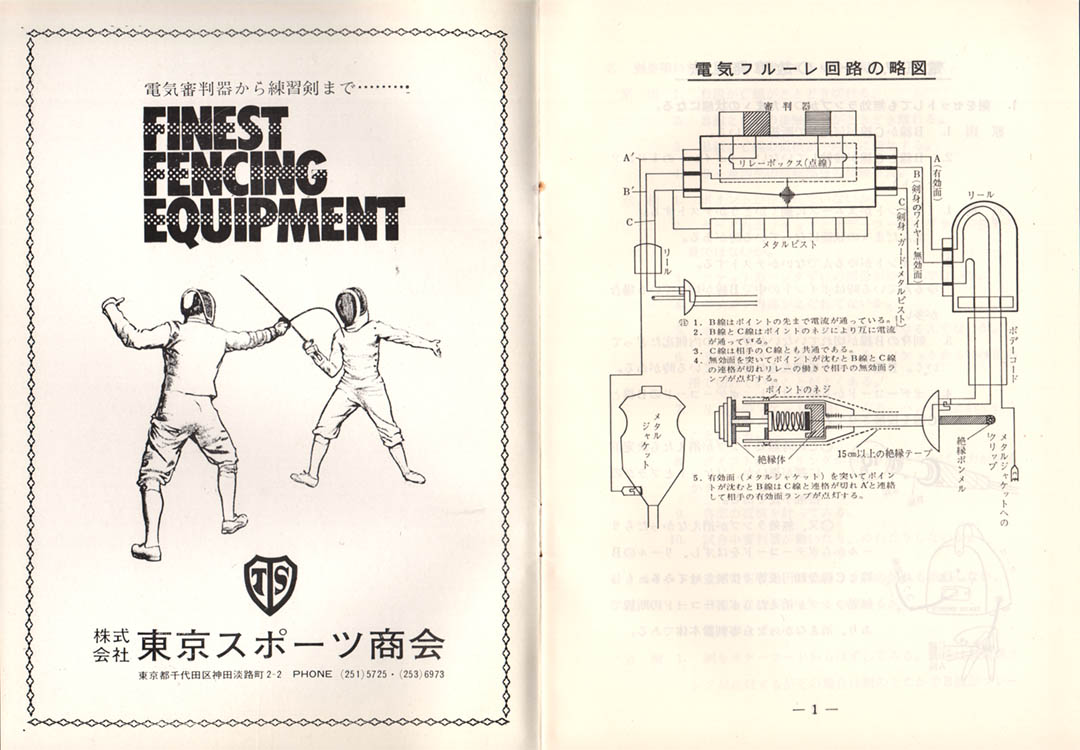

The above is the first page inside the main Tokyo Sports fencing equipment catalog. On the left, you can see the “T/S” logo that you would find stamped on bell guards and such. The diagram on the right is a fascinating way to outline the complete circuit diagram for registering a foil touch. Few of these catalogs have publication dates, so it’s anyone’s guess when this is from. However, since the foil point in the above diagram is a ‘pineapple’ point, the drawing has to be from the ’60s. But on balance, the whole diagram looks like the layout for a small section of the Tokyo subway system. “Kanda to Meguro station in 12 easy stages!”

I don’t know how long, or even if, ever, Tokyo Sports dominated the Japanese market for fencing gear, but at some point they had competition in the form of Asahi equipment.

No dates anywhere that I could spot in the Asahi catalog. And if anyone can enlighten me as to what the heck that item on the cover is supposed to represent, I’m willing to entertain suggestions. A foil? A reproduction rapier of mysterious origin? Modern art?

As far as I can determine, neither Tokyo Sports nor Asahi are still in business. When they went under I’ve no idea, although I assume it was in the 1970s. Based on the number of other catalogs in the pile I pulled out of the files, the Mori’s were definitely keeping on top of what the competition was up to. Then again, I think a lot of these companies would use one another for suppliers of certain items, especially when one company had an exclusive deal with a manufacturer making something unique. I know Hans Halberstadt was the exclusive US distributor for Uhlmann machines and equipment for some period of time, likely due, at least in part, to the common language shared by Hans and Josef Uhlmann. For all I know they were pals while Hans still lived in Germany. Speaking of Hans…

Once again, not certain of the date of this catalog, but it references Hans Halberstadt in a way that infers he’s still alive, so pre-1966. This catalog actually has some things clipped out of it, but I can’t tell what the scissor-wielder was interested in.

Speaking of Uhlmann, they had catalogs for everything from scoring equipment to uniforms and everything in between.

This is the fancy-pants most modern of the catalogs in hand. Must be from the 1970s and it has some water damage, but there’s no mistaking the design of that guard socket. Hasn’t changed at all, has it? Although if I read the latest FIE missive correctly, they’re discussing making these body cord parts out of a see-through material. I guess someone figured out a new cheater wiring scheme. I don’t think it’s one that someone has been caught with, just a bug that could be exploited. Still, after however many years this has held up as-is, they’ve had a pretty good run.

More Uhlmann. That move the sabre fencer on the right is demonstrating in this photo? That’s illegal now. If you’re in the camp of loving the current state of sabre, we’ll just have to agree to disagree as to whether it ought to be illegal or not.

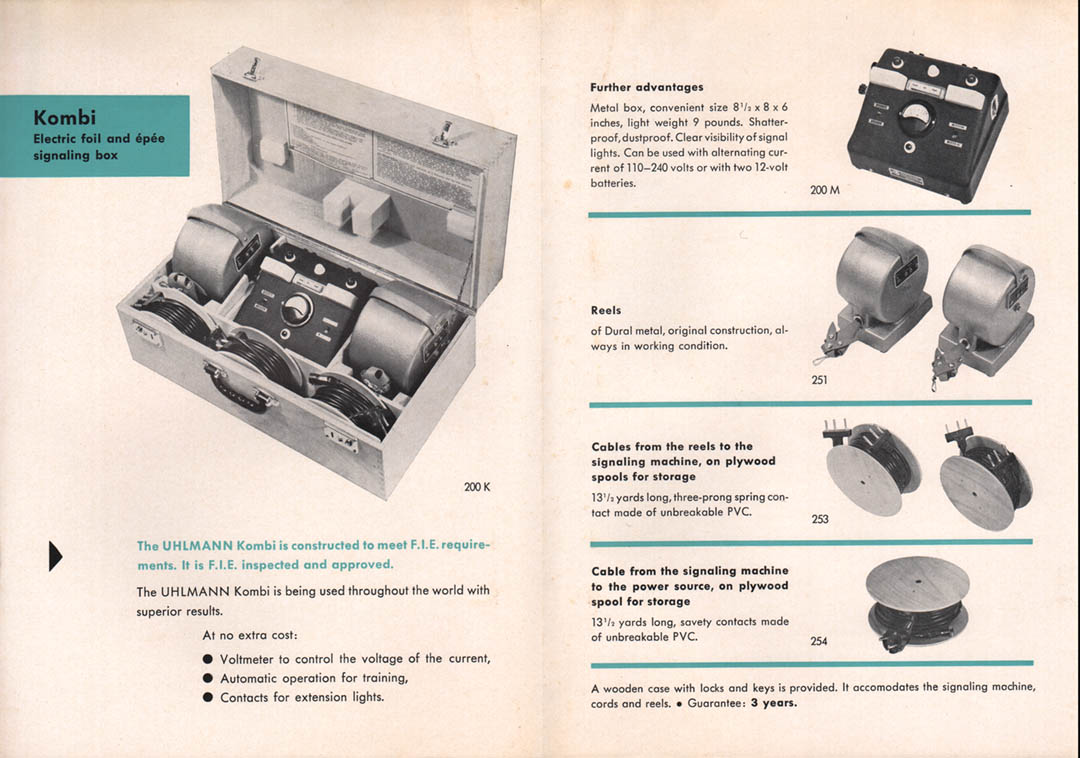

The scoring machine hardware manufactured by Uhlmann. This is the front and back page of this single-sheet catalog. Below is the inside.

The reels you see here, if you’ve never picked one up, double as boat anchors to keep them reasonably able to withstand the tug of the cable without following along behind the fencer like a puppy on a leash. Combine two of them with a scoring machine, plus reel cables, secure them in a hefty wooden box with a handle and you’re looking at flipping a coin to decide who gets stuck carrying this kit into the gym. I lost that coin-toss many times. These boxes were big, unwieldy and heavy. Well designed. Sturdy. They weren’t going to easily break down on you and were built to survive anything short of a direct hit from enemy artillery, but dang that’s a heavy box.

Of course, Uhlmann wasn’t the only name in equipment coming out of Europe. There was also Leon Paul out of London, around since the 1920s, but they aren’t represented in my stack of catalogs. Neither is France’s Prieur company. However, I do have an example of another French company, Soudet.

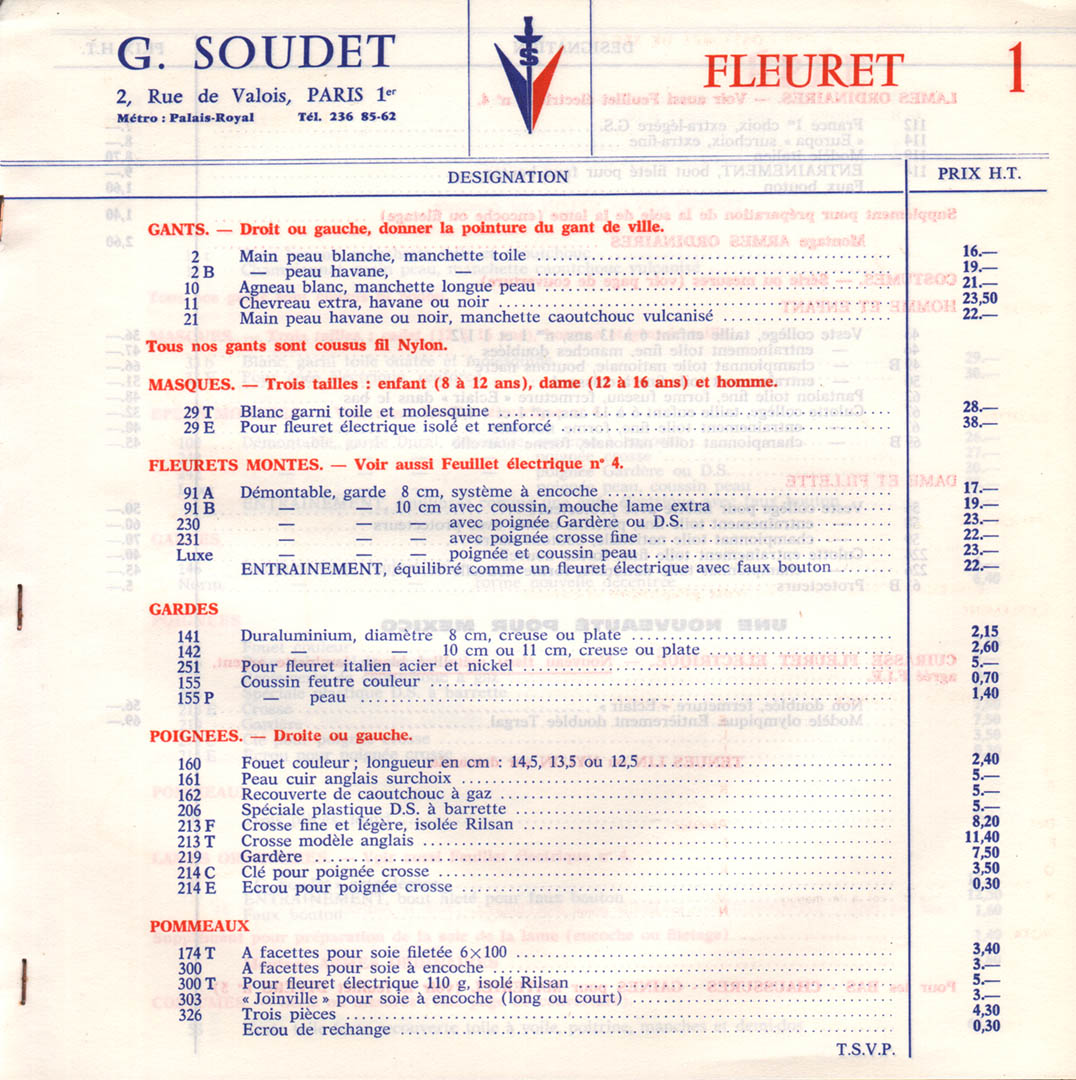

The Soudet catalog. This cover was torn or cut off the face of the catalog, but here’s the inside first page:

Mostly I’m avoiding showing much in the way of pricing, since it will just make those still in the market for fencing equipment really sad at how much prices have changed. Of course, since this catalog is all in French, I have to assume we’re looking at prices in francs not dollars, so what that would equate to in then-current dollars from a catalog I can’t date is anyone’s guess.

In addition to the above, there were of course all the east coast manufacturers and suppliers, of which there were many. Are any of these still around? I’m pretty sure not. Once the namesake for each of these suppliers passed on, the companies followed soon after. You can still find a lot of gear with these names on Ebay if you’re at all nostalgic for masks that do only a marginal job of protecting you. That’s just how they made them back then.

Founded and run by Gold-medal winning Olympian, Olympic coach and successful duelist Giorgio Santelli, the Santelli Company was in business for a very long time.

Here’s an example of a ‘school and club’ price list. The bread and butter customers of an equipment supplier, fencing clubs and school programs needed equipment in chunks, which allowed a supplier to cut them a deal on price. Often, too, clubs could then sell to their students at the usual price and make a little profit from the exchange. Santelli passed away at the age of 87 in 1985 and kept the equipment business going pretty much until the end.

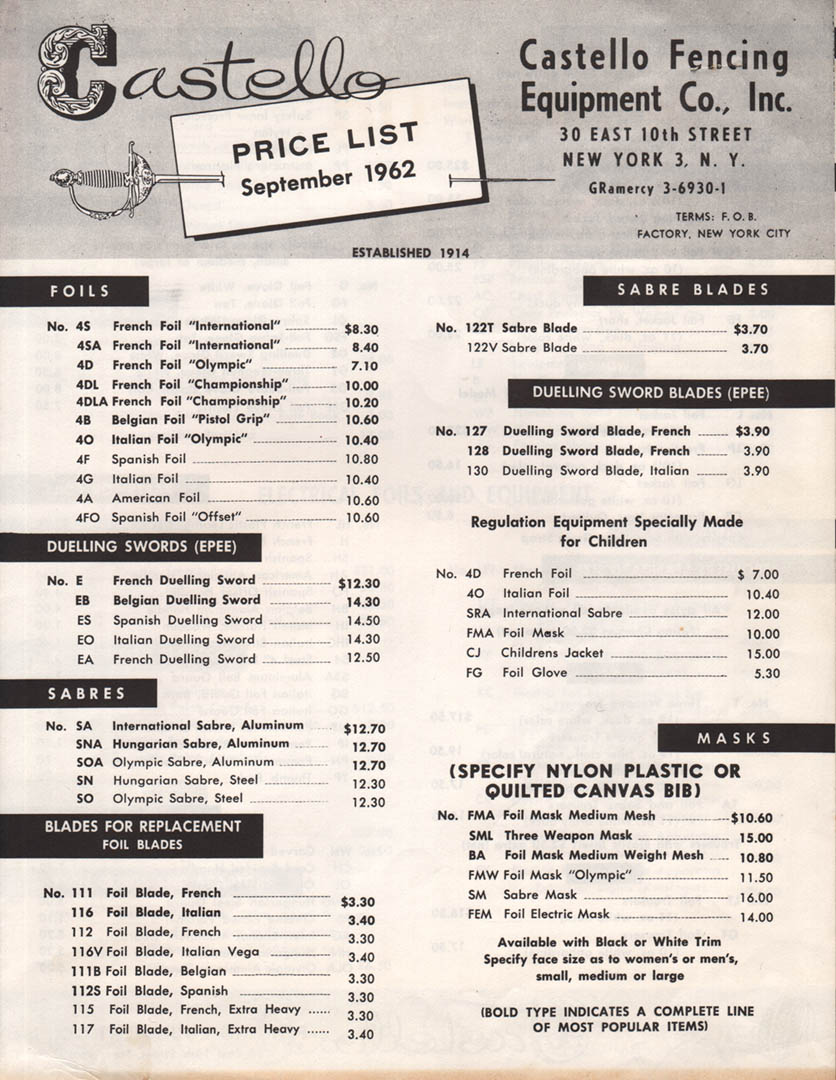

The other big east coast supplier was the Castello company, founded by the Spanish-trained maestro, Julio Martinez Castello, and carried on by his sons Hugo and James.

Ok, here’s a look at pricing from 1962. Read it and weep.

Oh, and there’s this, too! So if you don’t like the prices above, how about half off? Now how much would you buy? This was stapled to the above price list. If anyone has a viable time machine, you may want to consider tripping over to Manhattan to pick up a little bit of gear. Just remember that the masks, gloves, jackets, knickers and blades won’t pass an equipment check in any current tournament.

Last up, one that I can’t place.

I’m pretty sure I’ve never seen an example of a Statronic scoring machine. This advert, using three languages, is clearly aimed at an international audience, but I’m having trouble parsing their catchphrase. What exactly do they mean by “Missiles’ electronics at the service of fencing !” Does it mean that use can use this box to launch an attack on your opponent?

So, that’s what I was able to dig out of the files. I thought it might be interesting to get an overview of the days of yore and what was out there in the arena of fencing equipment. You know, just for fun. But if anyone does have a time machine, preferably with a safety guarantee, I’m interested.

There is one other large batch of pages for equipment available from Spain. Mostly replica weapons and other odds and ends – and there’s an implied emphasis on ‘odd’ – the papers include two suppliers, one of whom is Oscar Kolombatovich, the father of George K, who many of you will remember. Oscar made replica weapons – beautiful ones. I think I’ll save the Spanish stuff for next time. Stay tuned!

Indulging in Imagery

I have to face the fact that there is, for me, a certain romance in the imagery associated with fencing. This has been true for me as far back as I can remember. I don’t know what it is. Perhaps an atavistic memory engraved on my dna from the whisper of past lives trailing away into distant unremembered existences, an endless parade of reincarnations as this or that lordling, soldier of fortune or expendable henchman. You know, if you believe in that sort of thing.

On a more practical note, I’ve begun with the image up top because after a long layoff, too long, I’m going to get back into the salle this week. The last tournament I fenced in, a year ago June, the Charles Selberg Vet 50+ Invitational, cost me a torn hamstring to get into the top 4. Surgery in August last summer. Great surgeon, phenomenal PT. I’ve wanted to get back on the piste, but have been either too busy or too lazy. Too blazy? Can I say that? Well, time’s up. I’ve been hitting the non-fencing gym for the last few weeks and now it’s time to pick up a foil and see what happens. “Not much,” is likely going to be the answer. Still. I’ll happily advance and retreat a little bit to make myself a semi-moving target, just to enhance the experience for my opponents.

So to remind myself of some of the fencing images that make me happy, today I’ll indulge in some old school material from the collection of John McDougall. John is kickin’ it up in Southern Oregon these days, but when he ran out of storage space he sent his fencing memorabilia collection south to the Archive. He collected for many, many years and put his hands on some really remarkable items.

This is probably the only artist I can readily identify of the items I’m posting today. Josef Arpád Koppay was an Vienna-born Hungarian who originally studied to be an architect. Once his talent for painting was recognized, he studied under some famous painter then launched his own career, eventually becoming the Austrian court painter. Famous for portraits of the famous, somewhere along the line he painted a number of fencing ladies, of which this is one of three that John collected.

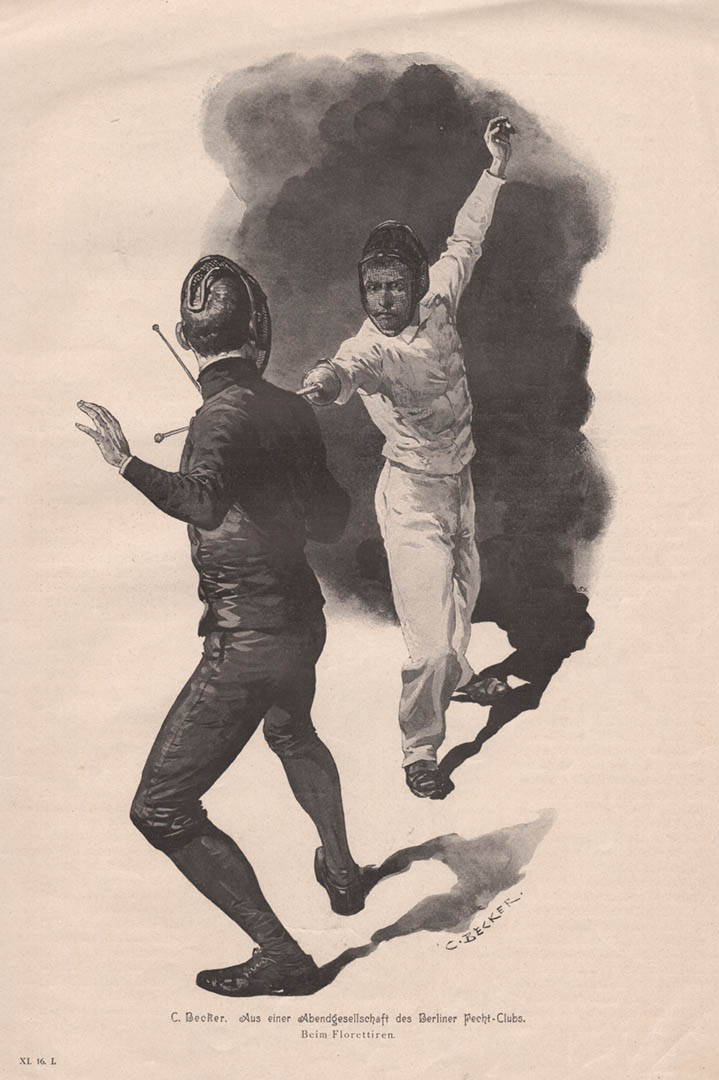

A prolific lithographer and engraver, C. Becker is otherwise someone I can’t track down. The contrast between the foilist in black and the foilist in white is nice, while the smoke(?) billowing out behind the fencer facing us makes it seem that he’s come forth like a genie from a bottle, foil in hand and ready for a bout.

One thing about buying graphic items on Ebay or at an antique store, like most of the selections today, is that you’re picking up things completely out of context. Many are cut out of books or magazines. Without any distinguishing text to say from whence the item originated, it’s really a challenge to figure out where something fits either in time or place. It’s nice to have the image – and since that’s really what I’m focused on today, don’t think I’m complaining (I’ll save that for next time) – but the hints you can pick up in the margins are nice to have.

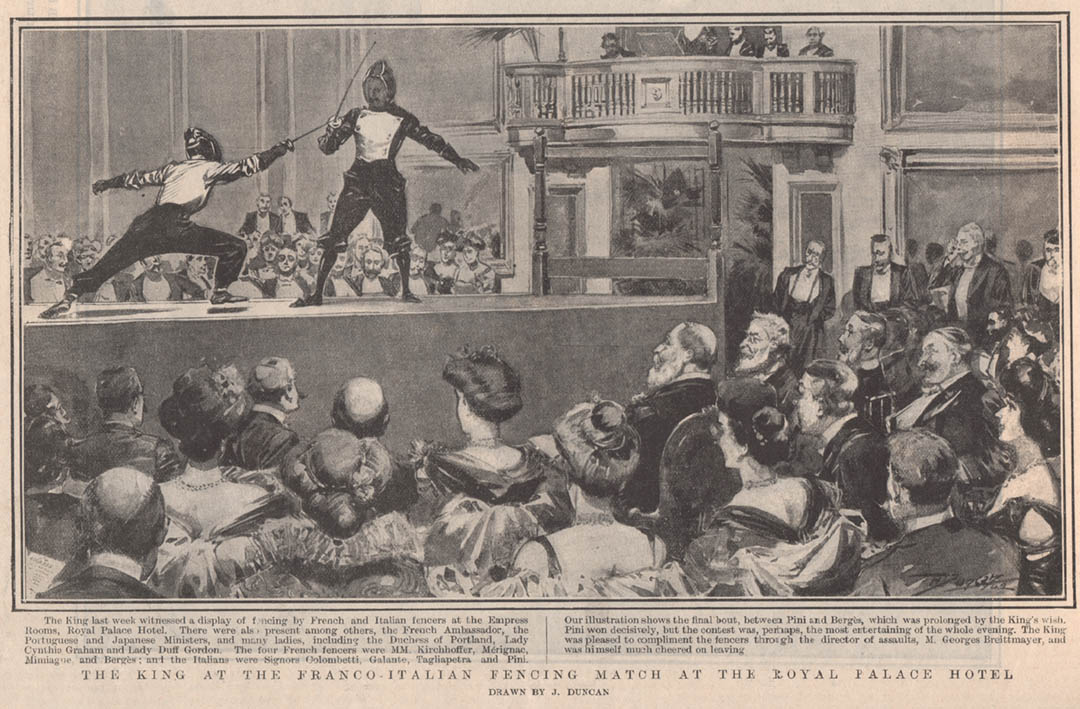

This one, at least, has a nice full caption to place the event in historical context. I’ve been able to use this image twice this weekend. I cut out the caption and used it in my homework for an online course I’m taking in entrepreneurship. Long story.

This one is definitely cut from a magazine. If you look closely, you’ll even see the ghosted image of the reverse trying to bleed through to the side I scanned. With better photoshop skills, I could work on the contrast to eliminate that, then add back in the sepia look of the old and yellowing paper, but the original look is how I’m used to seeing these old pages making me loath to make them look too new. They’re not new, so why fight it? I like that they look old. Hell, I look old and I can still stand to look in the mirror long enough to shave, so I’m not going to complain about a magazine page that has survived intact since the time of Edward VII. That also gives me a nice date range for this piece, too, as this version of King Edward reigned from 1901 to 1910, making this piece more than 100 years old. Nice! And, since he’s mentioned in the caption above as one of the participants on the Italian side of the King’s entertainment, let’s move on to this next dashing figure.

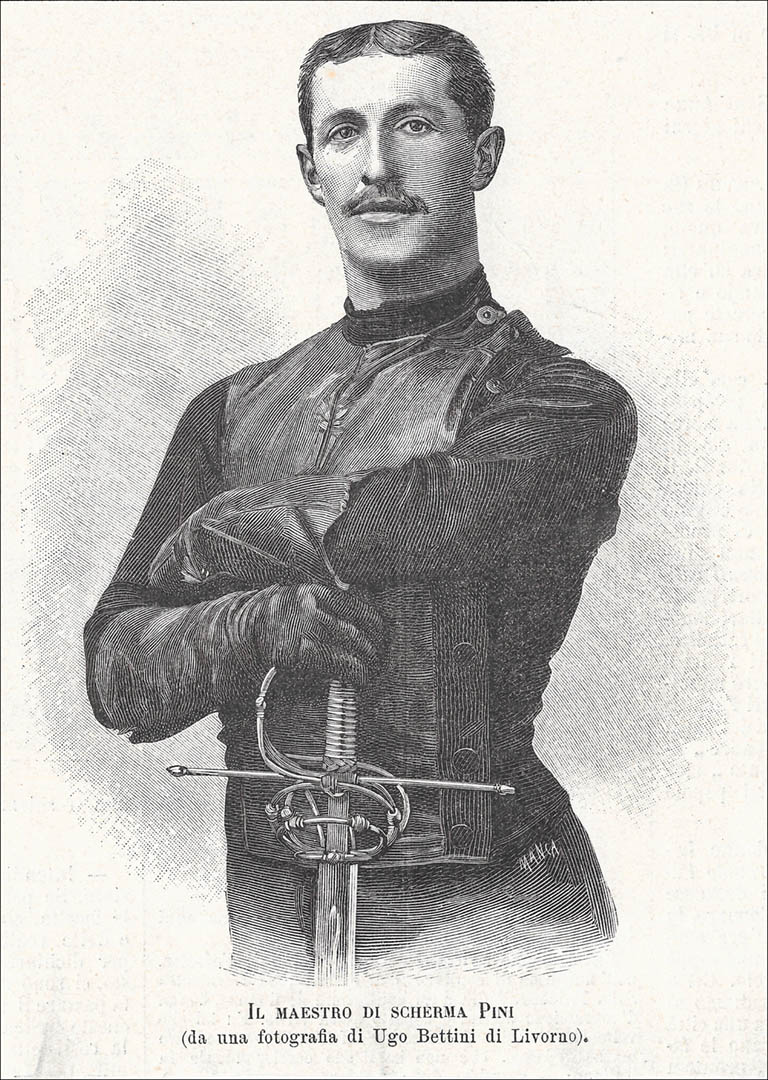

Eugenio Pini as a young man. Such a great image.

“Il Maestro di Scherma, Pini” was a larger than life figure and a highly influential individual. His exploits are myriad with duels a-plenty, arguments lasting for years, and he was one who influenced the sport of fencing for generations, helping usher in the new era of organized international competition. Among the many students of Pini was another from Livorno, Giuseppe “Beppe” Nadi, father of Olympic champions Nedo and Aldo. Pini would always dress in black for his demonstrations and challenge matches against his many fencing rivals, earning him the nickname, “The Devil in Black”. And, let’s face it, you can’t have a better nickname than that.

My fencing club looks just like this… in my imagination.

There’s no question that with three unused strips and three fencers lazing about, it seems like someone’s about to get hollered at to get out there and trade some touches. I mean, if it’s the bout o’ the night that’s about to take place, the bystanders don’t seem to be paying much attention. Another interpretation might be that the Master is watching his pupil perform the Grande Salute and the others are simply waiting their turn. I think that second one seems more likely.

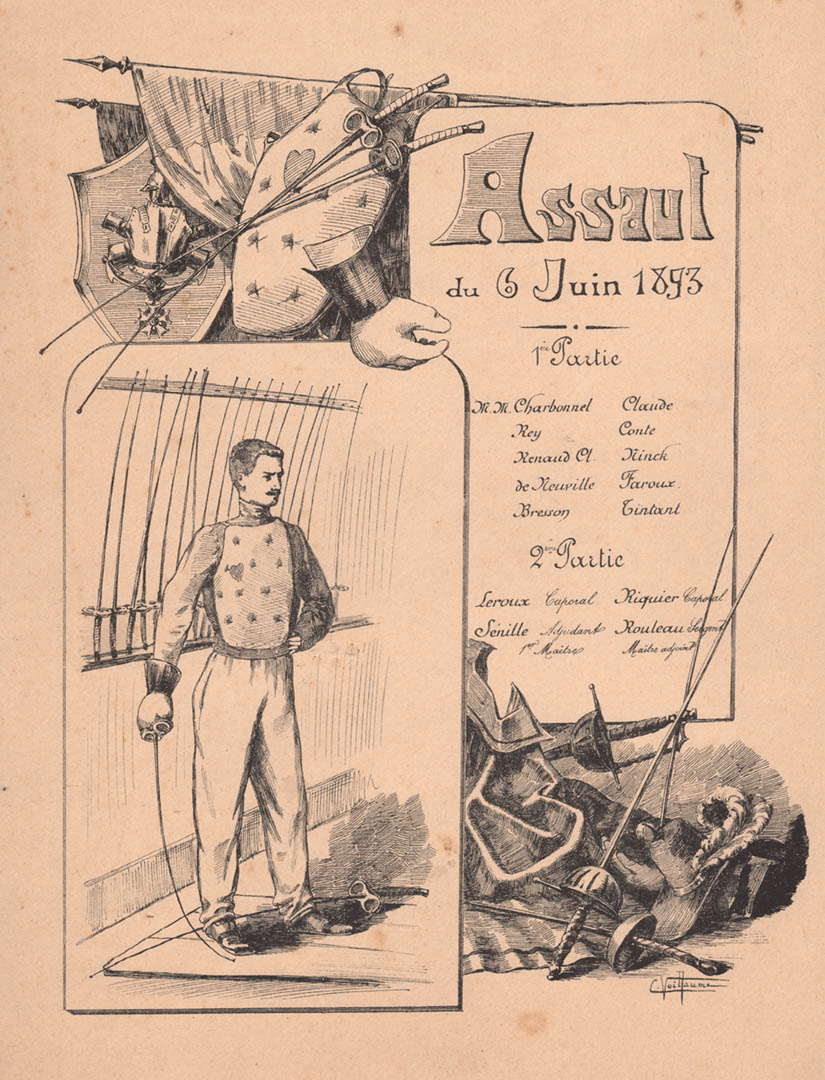

I don’t know where John picked up this handbill announcing an Assault of Arms, but it’s date of 1893 is right around the time organized competitions were getting set to become the standard.

These types of events were the pre-cursor to what we think of today as ‘fencing tournaments’. However, instead of arriving at a venue and fencing whoever shows up, in these older times the participants would go toe-to-toe with a specific adversary and try both to score more touches and show off the superior skills. The counting of touches would often be either disdained or considered gauche, I’m not sure which. These matches frequently resulted in arguments over just who had bested whom, the audience often split along party lines, be that nation state, style or club affiliation.

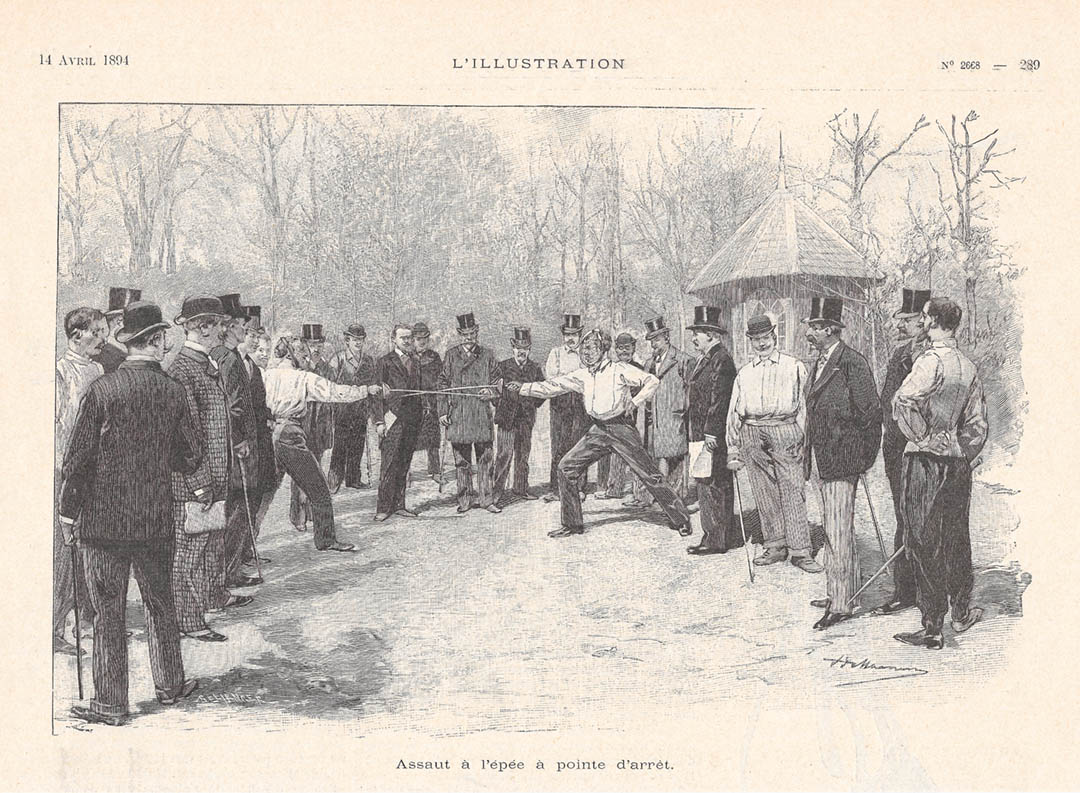

An 1894 page from L’Illustration, a weekly French magazine published from 1843 to 1944.

Of the age as the previous image, this one shows the transition to competition in action. At least, that’s how I’m interpreting it. Of the spectators standing around, the ones without top hats appear to be holding epees and are presumably awaiting their turn. The one guy without a hat standing between the two fencers who might be in position to be officiating the match seems to be holding onto a piece of paper that I’m going to construe to be a score sheet – or at least, an order of events. Maybe it’s just the handbill like the one above. At some point, scorekeeping became a thing to simply track rather than argue about after the fact. So much easier.

Ok, that’s enough of my digressions this week. Think good thoughts for my hamstring, if you will.

More Time with Jerry Biagini!

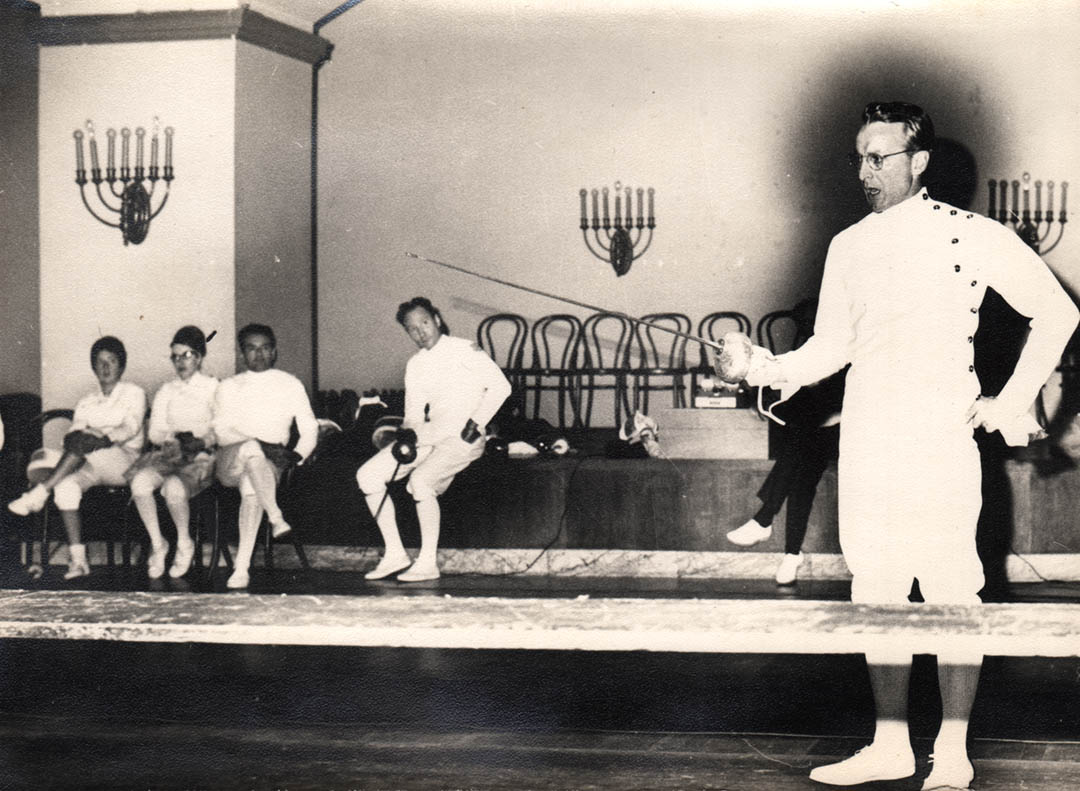

There is nothing in the world quite like Jerry Biagini’s greeting to me when I visited him about two weeks ago. Me: “Mr. Biagini, how are you?” Jerry: “I’m 90 years old and cranky!” As it turned out, he wasn’t so cranky as all that. We spent a good four hours talking fencing history and it was entertaining, enlightening and just an all around pleasant afternoon.

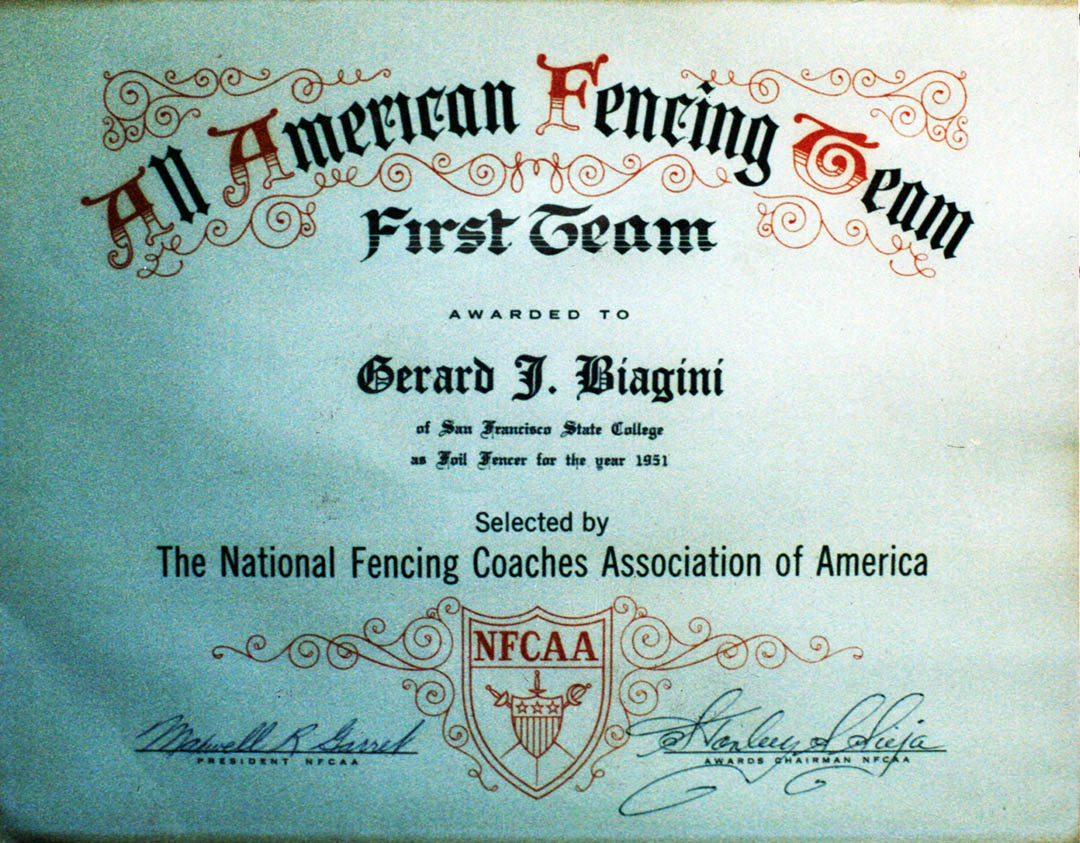

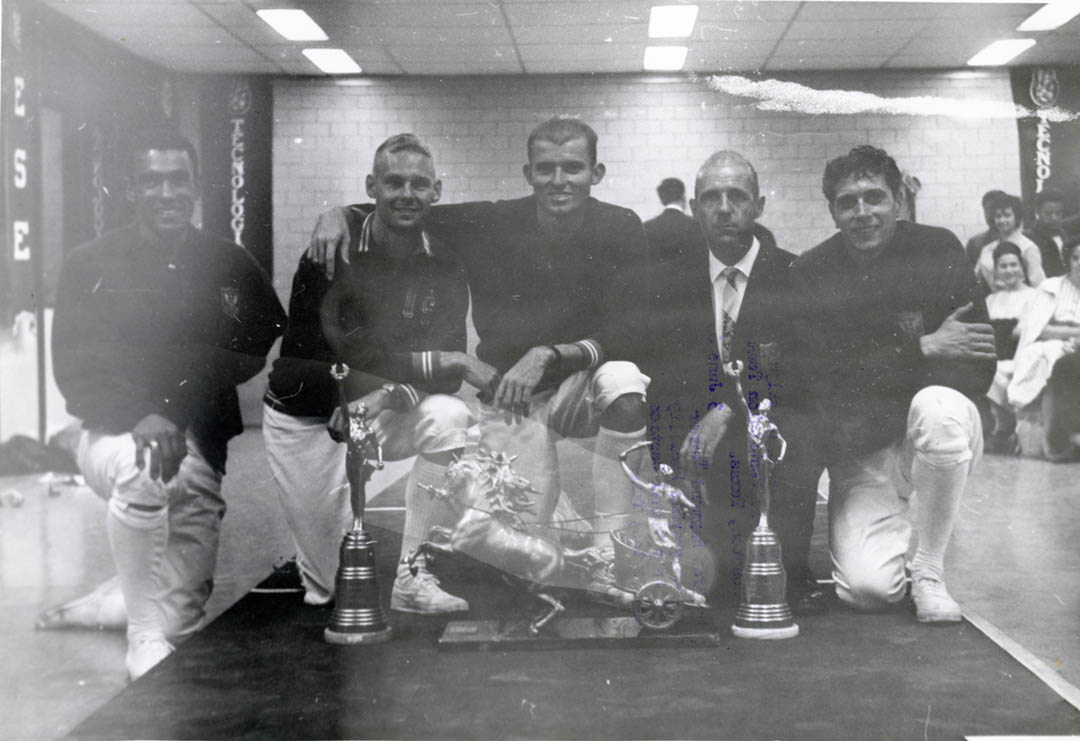

If you don’t know his history, let me do a quick run-down. He started fencing in San Francisco in the late-1930s at the Unione Sportiva Italiana under Edward Visconti. He went to college in San Francisco, was an All-American, taking 2nd at the 1951 NCAA Men’s Foil championship and was named to the US National Foil squad for the 1958 World Championships in Philadelphia where he made the semi-finals and finished 12th. A five-time National medalist in Sabre team, his Pannonia squad won the title twice. He also won multiple Pacific Coast championships in all three weapons and started the San Francisco High School fencing league, ran it for decades, and it still continues to this day.

And in 1965, he and some friends gave a fencing demonstration to the Masons at the Argonne Lodge in San Francisco. Jack Baker was the front man and did the talking, it seems. He was, at this time, the Vice President of the AFLA (now USA Fencing) and was likely the organizer of the event. The participants included all those listed on the handbill above, with the addition of Iris Lucero who, for some unknown reason, didn’t make the program listing. That said, it was quite a line-up. Along with Jack and Jerry, there was Olympic Gold Medalist Dan Magay and Harriet King, a multi-time (for both) Olympian and US National Women’s Foil champion. So the Masons got their money’s worth.

Jack Baker explains the intricacies of the epee while Harriet, Alice, Dan and Jerry look on. I tried to find a record of the Argonne Lodge of the Masons in San Francisco, but they seem to have disappeared after the 1970s. Founded by veterans of the WW1 battle of the Argonne, it may have been folded into another Masonic group in San Francisco or just ran out of members. There are still several Lodges in the city today, but this one is no longer mentioned as being among them.

The event seemed to have been well attended by the Masons, and appreciated. Their newsletters, several of which are preserved in the pages of a scrapbook of Jack Baker’s that Jerry, the now-owner, allowed me to borrow and scan (the images today are all from that scrapbook), have articles both before and after the event extolling the most excellent demonstration put on by the visiting fencers. And they served cake after the demonstration, so everyone came out a winner.

The fencers actually got two cakes! One a “Welcome” cake and the other with their names inscribed in frosting. Iris, again, didn’t make the list of participants, but Ferenc Marki did.

The crowd at the Mason’s Lodge enjoys watching Maestro Ferenc Marki put Jack Baker through his paces in sabre. Now why Jack was getting the sabre lesson demo over Olympic Gold Medalist Dan Magay, who can be seen sitting watching, his head just under Jack’s chin, is a mystery. Maybe Jack was a Mason and wanted to be in the spotlight. While he was a solid fencer and member of a couple of Pannonia’s National Champion sabre teams, one of the greatest sabre fencers of the late-50s, early-60s has been left on the bench. If this was my fantasy fencing team, I’d have made a switch here before game time.

The best thing about this scrapbook, however, is not the Masonic demo, but rather the information it contains about Jerry Biagini’s fencing career. Jerry and Jack were close friends and Jack obviously took pains to preserve some photos and other items he had that spelled out details about Jerry’s fencing career.

The above is a photograph, presumably taken by Jack Baker, of Jerry Biagini’s All-American certificate for his performance at the 1951 NCAA Championships. Jerry took second at this event and it was the only year he competed at collegiate nationals. He finished behind Bob Nielsen of Columbia and ahead of 3-time Olympian Hal Goldsmith of CCNY. Shout out to George Masin for the excellent documentation he is doing on the complete history of the results from the NCAA fencing championships.

Jerry de-planing after his return flight from Illinois after the NCAA’s. From my childhood, I remember the Western Airlines jingle very well. “Western Airlines…. the ooooooonly way to fly!” Of course it’s the animated commercials I remember. You can watch them on YouTube!

Jerry’s fencing master, as I mentioned above, was Edward Visconti. Visconti retired as a coach when Jerry was still a very young fencer. He helped Hans Halberstadt by providing him with the seed equipment to open the Halberstadt Fencers Club in 1941 after his own club was shuttered by the government due to concerns about Italian fascists infiltrating or influencing the club members. Jerry didn’t pick up another coach. He went without regular coaching until a new player arrived on the scene. The final stop on the cross-country tour undertaken by members of the Hungarian Olympic team in 1956 to raise money for Hungarian refugees, who were welcomed with open arms by the US, was in San Francisco. (More here.) At the event, Jerry and Visconti were introduced together to the great George Piller. Visconti didn’t have any Hungarian and Piller’s Italian wasn’t great, but they got by speaking in a mix of French and Italian. Visconti and Piller were both WW1 veterans – Visconti came to the US shortly after that war – both were decorated veterans, both had trained at Military Academies. Immediate friendship, mutual respect. Visconti asked Piller, “Maestro, will you please teach my student?” Piller replied, “If I remain in San Francisco, I would be honored.” Well, stay he did and coach Biagini he did, too.

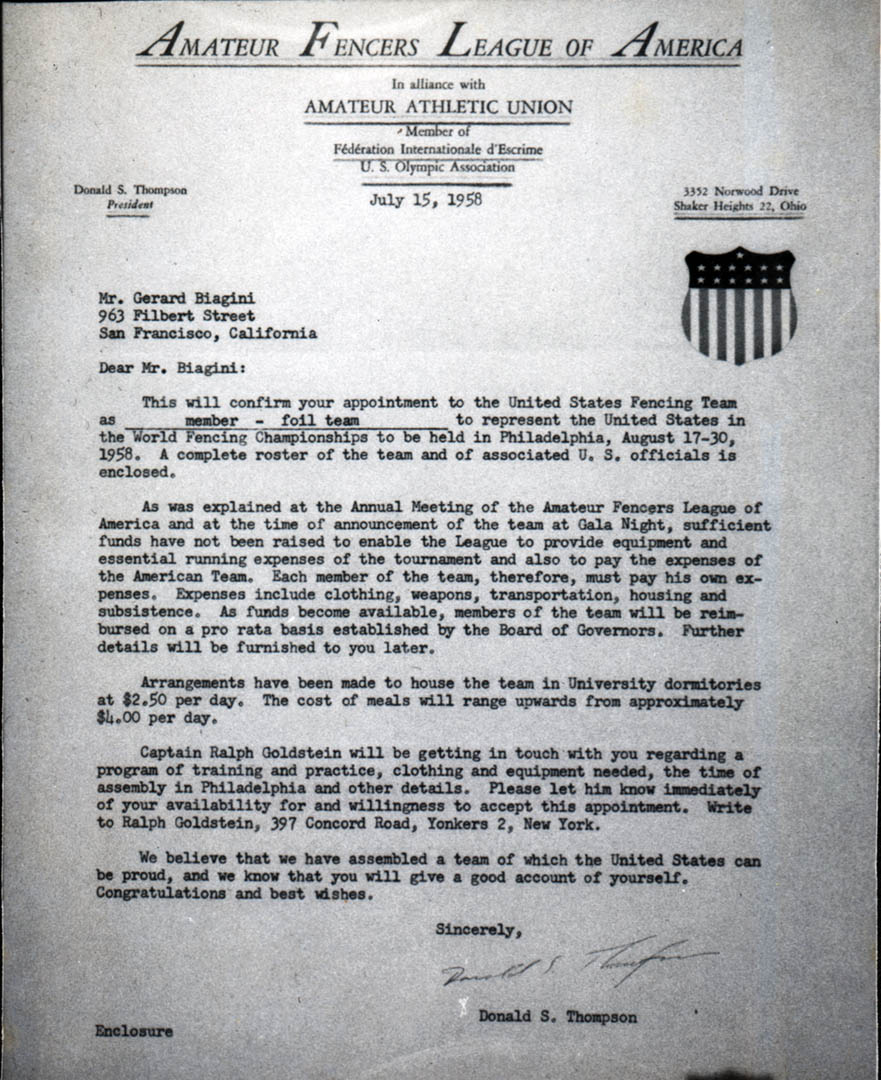

A photographed copy of the letter Jerry received informing him of his selection to the US Men’s Foil team for the 1958 World Championships held in Philadelphia. Note the date of the letter, July 15, for the event a month later and oh, by the way, we’re not paying any of your expenses. Travel, housing, equipment, everything was coming out of the pockets of the participants. Ralph Goldstein would inform Jerry of how to train and won’t you please write him back to say if you’re coming? Think things have changed much for US fencers representing the US on the international stage? Maybe just a little, huh?

Since I have it, below is a three minute clip of film footage taken by Torao Mori at the 1958 World Championships. They were held at the University of Pennsylvania in the Hutchinson Gymnasium and while there isn’t any fencing in the clip, it does show an overview of the venue and near the end a shot of the large scoreboard for the 8-man Men’s Foil finals that included Albie Axelrod, still two years shy of his Bronze Medal performance at the 1960 Olympic Games.

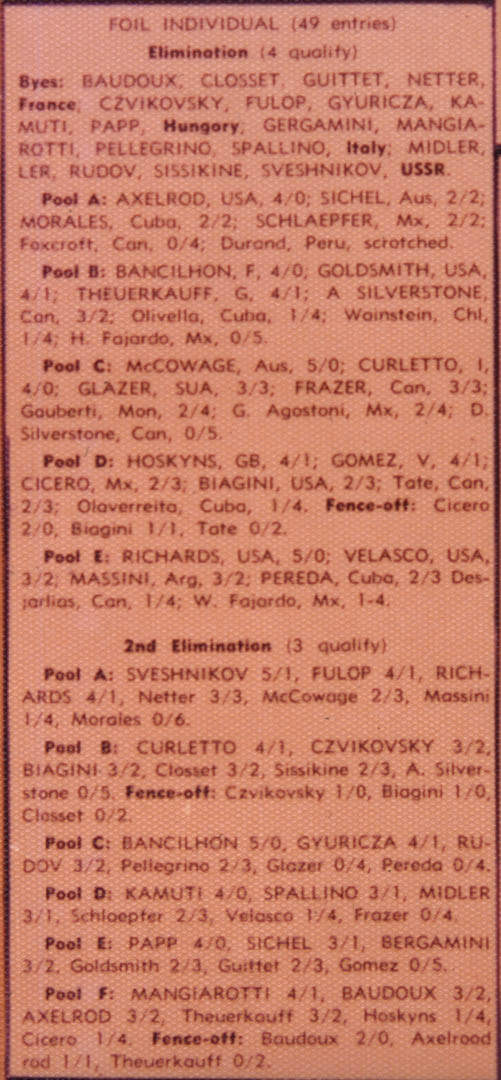

No sound on the clip above. Jerry Biagini and the other American fencers performances are spelled out in the two news clippings below:

In the first round, all the US fencers advance. Pool A: Axelrod, Pool B: Hal Goldsmith, Pool C: Gene Glazer (mis-labeled as representing SUA instead of USA), Pool D: Biagini after a 3-way fence off, Pool E: Ed Richards. In round two, Glazer and Goldsmith are eliminated and Axelrod, Richards and Biagini advance, with Biagini once again in a 3-way fence off. Here’s an odd thing, though. The first round has pools of 6 & 7. Axelrod is in a pool of 7, but one fencer is scratched, so 5 bouts. In the second round, there’s still a pool of 7. This is arranged because the fencers with a first-round free pass (in fencing parlance, a ‘bye’) have now entered the field, so they still had an odd number to divide. But pool D and pool E, both pools of 6, don’t finish all their bouts, my assumption being that the last bouts wouldn’t figure in who was or wasn’t advancing. Albie advances after a fence-off, so he’s now fenced 12 bouts. Jerry, with fence-offs in each of his first two pools, has fenced 13 bouts. Five of six fencers with first round byes have only fenced 4 bouts and the rest 5 or 6. Ed Richards, advancing without any fence-offs, has 10 bouts under his belt. It pays to get those byes.

In the quarter-finals, Axelrod goes undefeated. Counting his fence-off bouts, his overall record is 14-3 going into the semi-finals. Ed Richards goes 2-3 and has a fence-off where he loses to Baudoux of France and goes out. Biagini again has a 2-way fence-off with a 2-3 record and splits the fence-off, 1-1, and advances. Jerry’s overall now stands at 10-10 and he’s fenced twice as many bouts as every other fencer he’s going to face in the semi-finals. Where he goes down with no victories and 4 defeats. His last match against the Hungarian Gyuricza, the 1954 World Champ, isn’t fenced as the results are already determined. Axelrod toughs out a 2-3 pool record and has to beat Kamuti and Fulop, two tough Hungarian bouts, in a fence-off. So going into the final, Axelrod is 17-6 overall, 23 bouts, compared to almost all of the other finalists having fenced 15. Biagini and Axelrod were the only fencers to get into the semi-finals that didn’t start the day with a bye in the first round. Axelrod finishes in 5th place, Biagini 12th. What could Albie have done if he’d fenced 8 fewer bouts going into the final? As it was, he still defeated the eventual winner, Bergamini, 5-1, the only loss in the final for the champion. Axelrod, at 20 wins, 10 losses, has an overall winning percentage of 66%. Bergamini’s record of 15 wins, 6 losses on the day, gives him a 71% winning percentage. The 2nd & 3rd place finishers both had overall winning percentages of 64%. Fun with numbers! Draw your own conclusions!

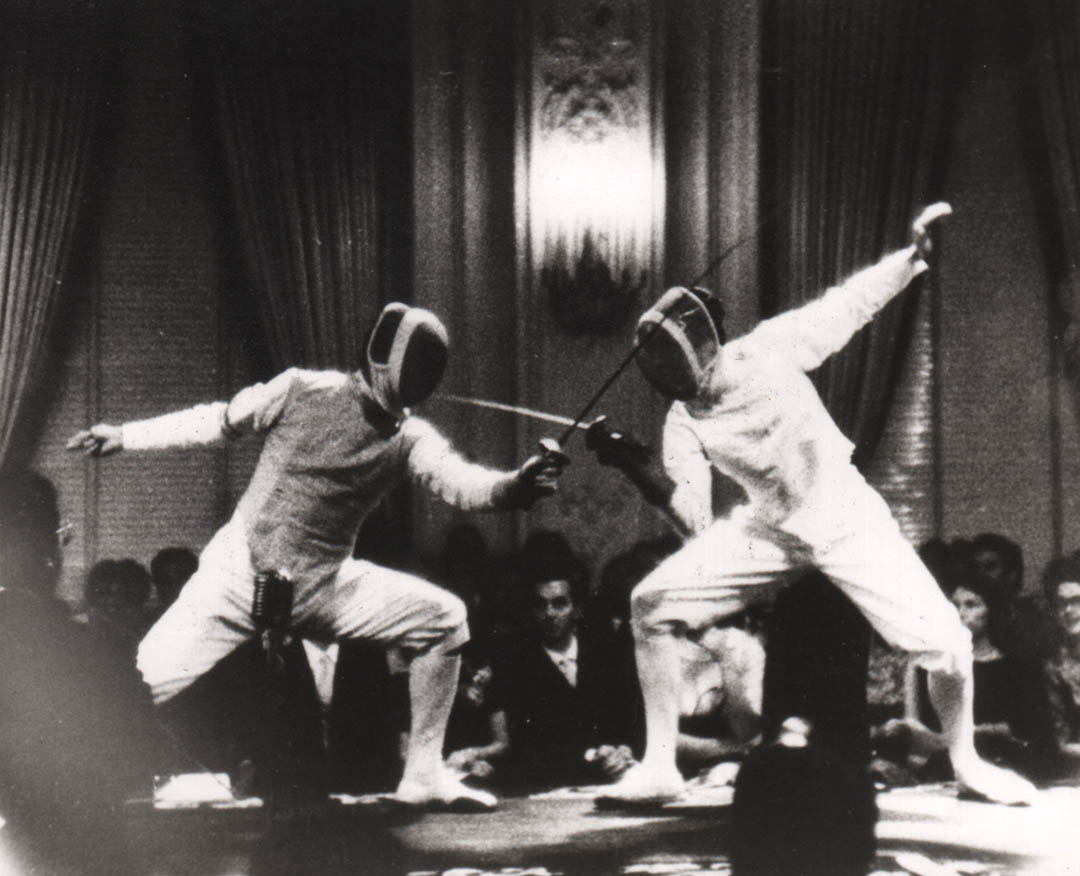

Jerry got a little bit of a reprise later in 1958 when the Italian teams made a trip across the US and stopped in San Francisco for an exhibition match held at the Fairmont Hotel. (See here for more details on that fabulous evening of entertainment.) Above, Biagini on the right is up against his World Championship semi-final opponent Edouardo Mangiarotti. They both went out in that round. I have in the Archive all the extant negatives shot that night by John McDougall. This is one of John’s photos, but, sadly, this negative didn’t survive to come my way. Somehow, and most fortunately, Jack Baker seems to have taken a photo of a print of this image and it’s in his scrapbook.

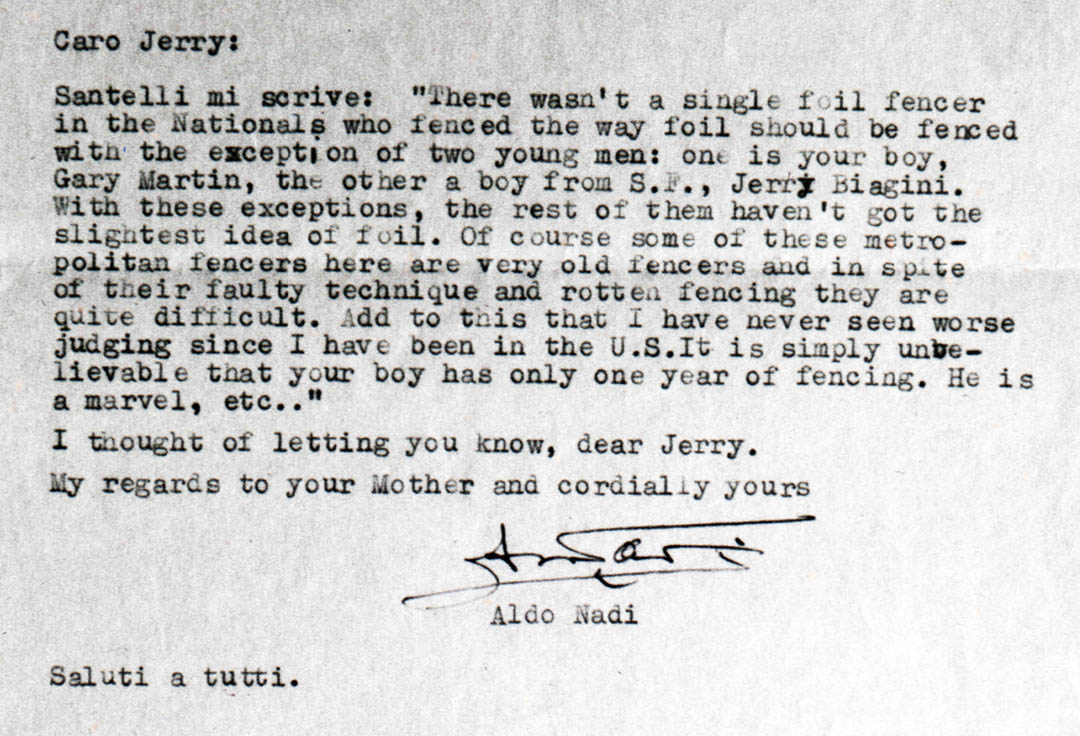

As a one-last-thing to mention, there’s one other little tid-bit that was in the scrapbook that I have to include. This is from an earlier date than most of the above-mentioned history, but in my mind, it’s saving the best for last. And how Jack Baker got a photograph of this document, I can’t guess. I don’t know if Jerry still has the original, or not. I will ask him when I return the borrowed scrapbook, now that I’ve got it scanned. The interesting thing about all these documents above that I scanned from the scrapbook, they all are photographic prints. My brother the professional photographer thought they looked like contact prints, so they would have been shot with a large format camera of some type, or maybe Jack was a home-photographer and made enlargements on photo paper from his own negatives. I don’t know. Obviously. But he did take a picture of the following letter, dated July 10, 1949, just a few weeks after that year’s US National Fencing Championships. I’ll allow Aldo Nadi to have the last word today as he relays some interesting opinions from Giorgio Santelli. Cheers!

The Spartan Women, Part One

The last article I wrote, which featured Michael D’Asaro’s time in San Antonio and the Army, got me thinking about one of the reasons I decided to attend San Jose State to train with him. That reason was the awesome strength of his Women’s foil program. However, when I started at SJSU in 1979, the original group that had set the standard of excellence for which the program had achieved national recognition were still around, but had completed their bachelor’s degrees and been replaced on the school’s team by a new generation of women who were to be my teammates and, in the case of two of them, my housemates.

The documentary film about Michael D’Asaro that I and my co-producer Greg Lynch are working on afforded me the opportunity to interview many of the women who helped establish the San Jose dynasty in foil and gain a much more complete understanding of how it all came about. Since the focus of the film Greg and I are working on is Michael, not all the specifics we learned may prove to be the details that will move his story forward, so I figure it’s not giving away the plot by writing about some of the things we learned. So the story at San Jose has to start with the three fencers who were the cornerstone upon which the San Jose State Spartan’s women’s fencing program was constructed: Gay, Vinnie and Stacey.

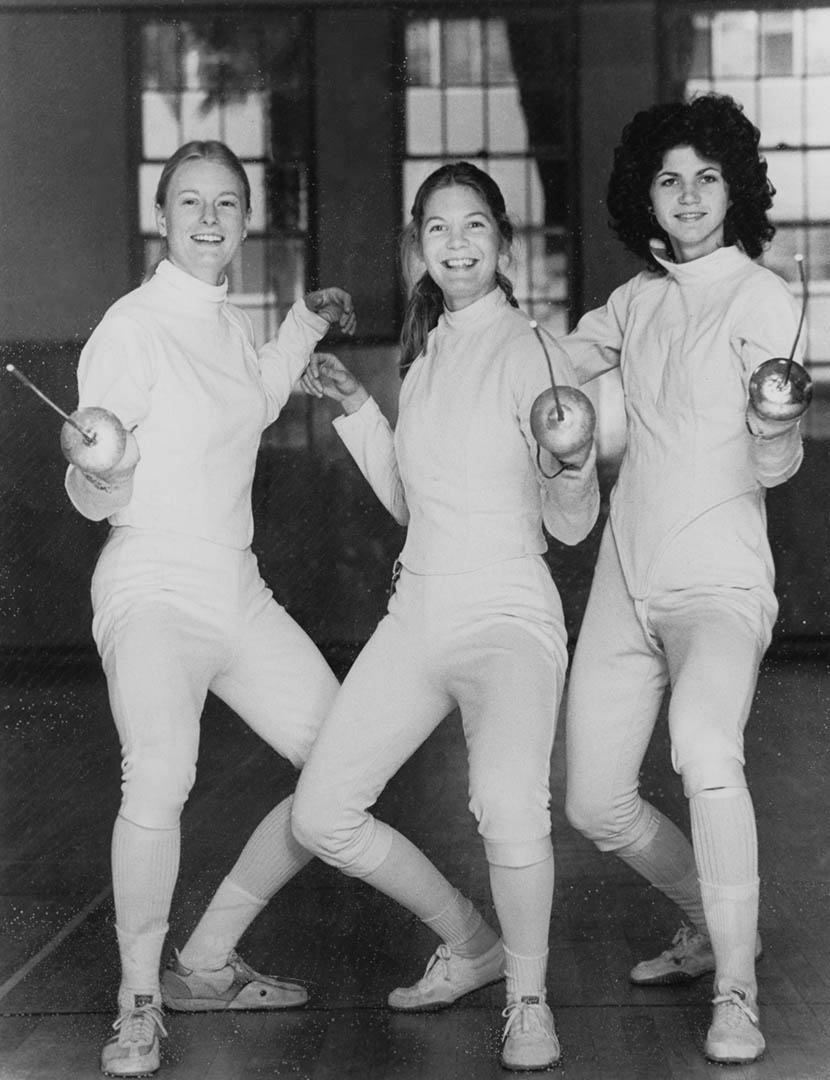

Left to right are pictured Gay (then) D’Asaro, Stacey Johnson and Vincent “Vinnie” Bradford, standing on-guard in the 7th Street Salle at San Jose State. The room is still there, but all traces of its fencing glory days have been sanded away from the walls and floors.

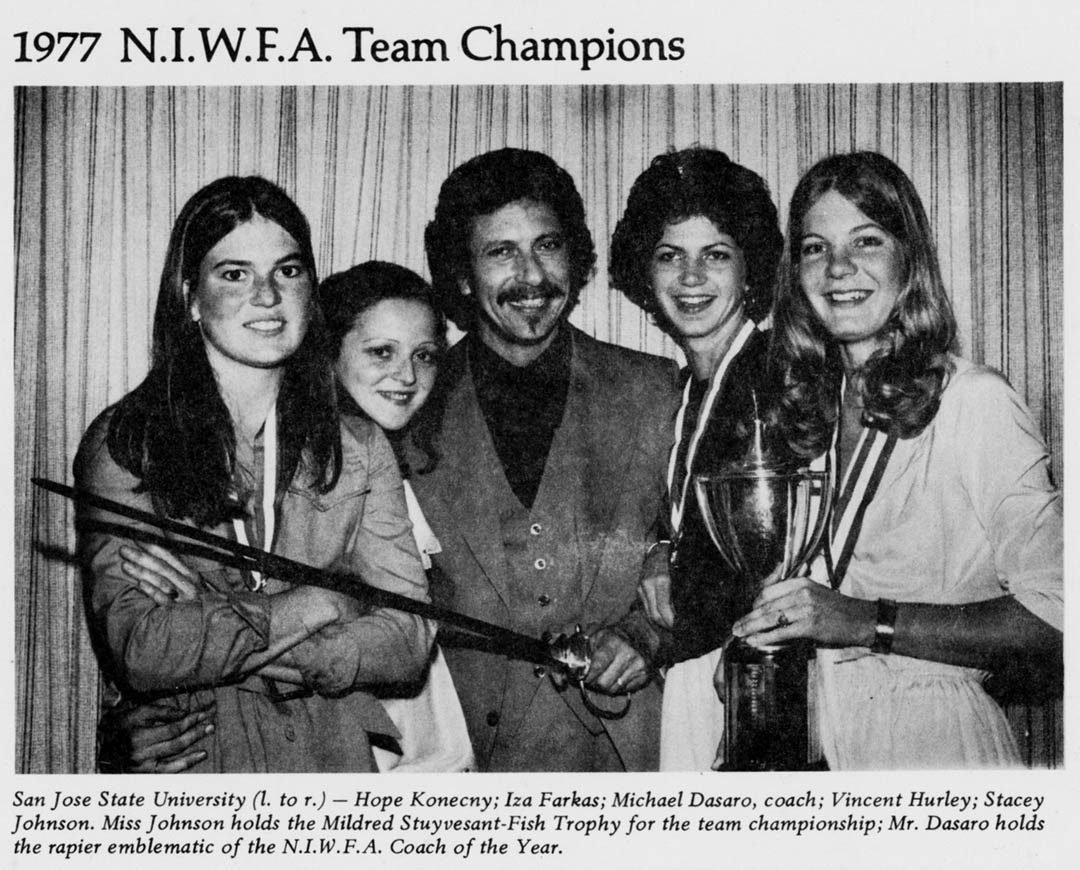

I always heard them referred to in that order. Gay, Vinnie, Stacey. Don’t know why, but always. They each had great success as student/athletes both collegiately and on the national stage. All three were Olympians; Gay in ’76 and ’80, Stacey in ’80 and Vinnie in ’84. Stacey and Vinnie each won the individual NIWFA collegiate title twice. Gay won two US National Women’s Foil titles. Vinnie remains the only woman to win both the Women’s Foil and Epee National titles in the same year and captured a total of 4 Epee titles. All three were on Junior World teams, often together.

This undated photo has to be from the first year of Vinnie and Stacey’s arrival in San Jose, so probably 1974 or 1975. Unfortunately I don’t know the name of the 4th teammate here. L-R: Gay, ???, Vinnie, Stacey.

Vinnie and Stacey both grew up in Texas at a time when young girls were not commonly seen at fencing tournaments. Vinnie described meeting Stacey for the first time when she was 15. Stacey was blonde and petite, Vinnie was 6 feet tall at 15, and Vinnie was entirely prepared to hate Stacey on sight. In their first meeting on the strip, the director didn’t bother to keep time and Vinnie remembers the bout being seemingly endless. This was back when women’s bouts went only to 4 touches, remember. At 3-3, la Belle, Vinnie parried Stacey’s attack and planted her riposte, bell-guard first, into Stacey’s mask. Stacey went down, shook off her mask, took a little time to recover under the ministrations of concerned on-lookers, got back on the strip and proceeded to score the final touch and win the bout. After the match, the two agreed they’d be better off as friends than enemies. Vinnie met Gay while on a Junior World team, and introduced Gay and Stacey to one another at the following Nationals in 1972. That was also when Stacey and Vinnie met Michael D’Asaro, who had been Gay’s coach since she was 14. Michael stood out from amongst the other coaches with his long hair, purple bell bottoms and wild shirts. Stacey and Vinnie began formulating the idea of how great it would be to both team up with Gay and train with Michael. After graduating high school in 1974, the two pooled their resources and cash totaling $700, got in a car and drove to San Jose. Michael helped them get on their feet as they found an apartment and part-time jobs, eventually landing them scholarship money. This, after both had been heavily recruited by East Coast schools, particularly NYU. In fact, the NYAC offered to sponsor them as the nucleus of a women’s foil team, which would have been the first women’s fencing team at the NYAC. Still, the lure of California, Gay as teammate and Michael as coach proved too strong.

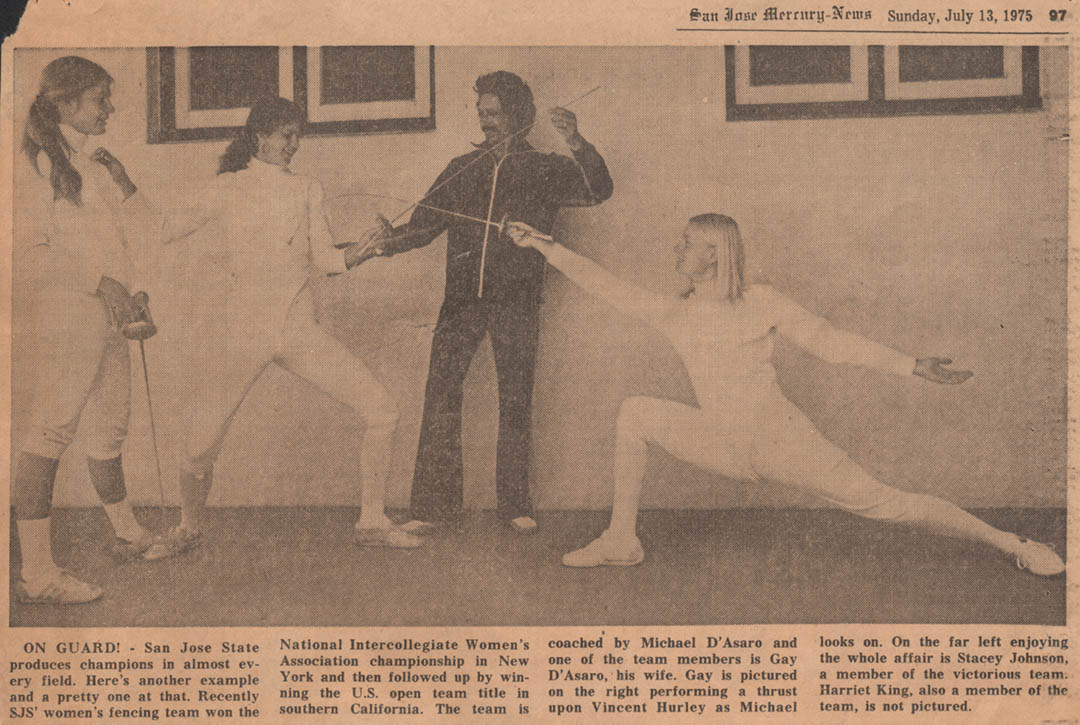

A San Jose news clipping from 1975 extolling the accomplishments of the local fencers, winners of both the collegiate and US National team titles. For the Nationals, these three were joined by four-time Olympian and four-time National Champion Harriet King, who trained with Michael when he was the coach at Halberstadt Fencers Club in San Francisco from 1967 to 1973.

Stacey began her fencing under the tutelage of Gerard Poujardieu, a French-trained master who worked with the pentathletes in San Antonio. The product of Catholic schools that enforced right-handedness, Stacey said that one day during a lesson, a frustrated Poujardieu said, “You couldn’t be worse if you used your other hand!” and had her switch her foil to her left hand. That, as they say, was that. A natural lefty, she excelled from that point on. She had already done well in equestrian events, but fencing proved to be the sport that truly captured her imagination.

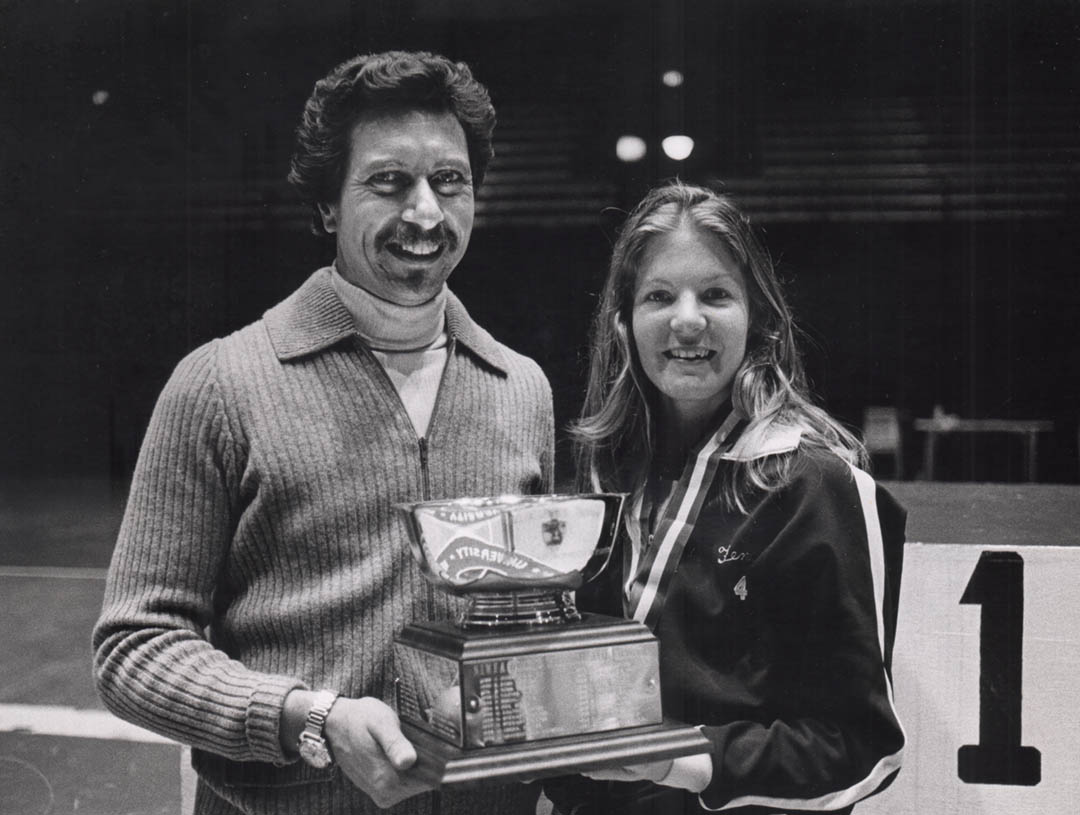

Michael and Stacey with the award for one of her two NIWFA Collegiate individual championships.

Gay, a native Californian from Ripon, a farming community in the Central Valley, first learned to fence in the garage of a neighbor who knew enough to teach her the basics. As she improved, he suggested to her parents that she could truly excel if they took her to San Francisco to learn under a fencing master there – Hans Halberstadt. They made an appointment for a saturday and drove the hour and a half into the city only to find a note on the door of Hans’ club & home that Hans was ill and lessons had been cancelled. Hans passed away just a few days later. At a San Francisco tournament some months later, Gay and her parents met the new coach at Halberstadt, Michael D’Asaro, and he convinced them to begin bringing Gay into the city for lessons, eventually settling into the habit of making the trip twice a week. Gay spent two years studying at the University of California Santa Barbara before Michael landed the job at SJSU. Once that happened, she transferred to San Jose to train and compete alongside Stacey and Vinnie for three years.

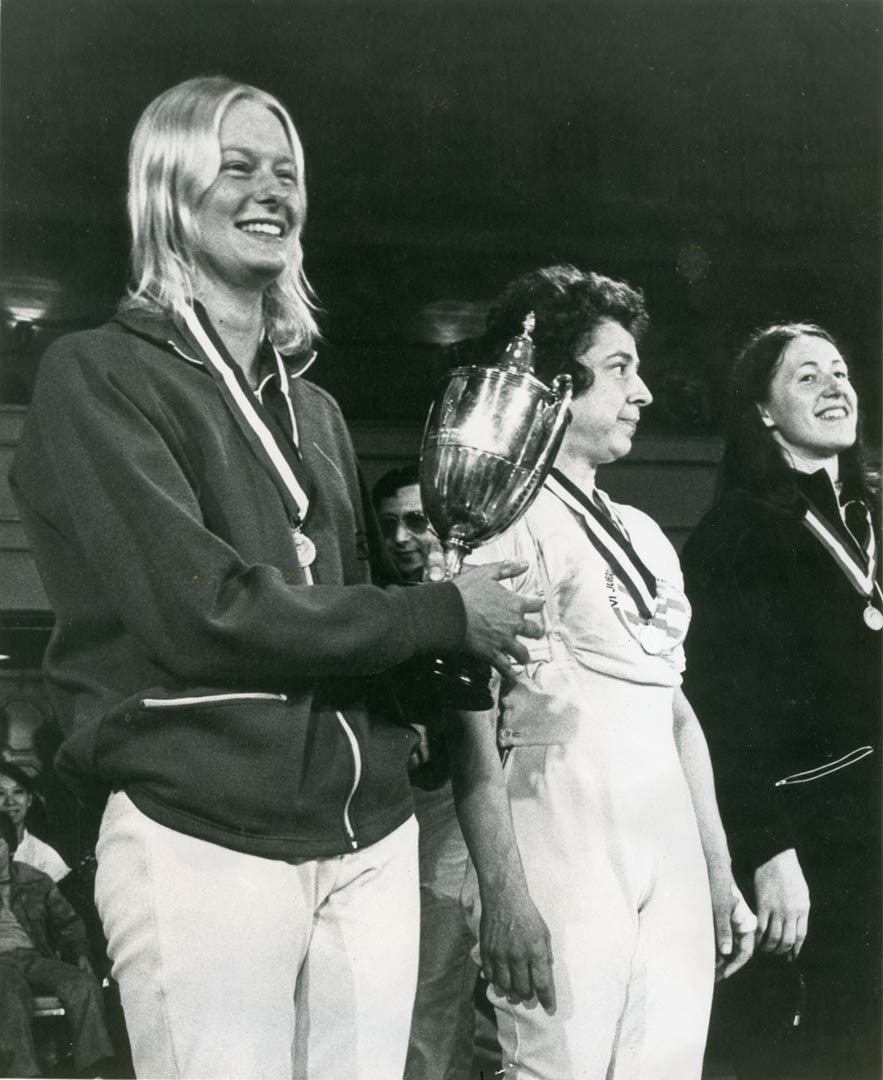

Gay with the trophy after winning the 1974 US National Individual Women’s Foil title. Harriet King, next to Gay, took second with a seriously injured fencing hand and in third, Pannonia’s Elvira Orly, giving the Bay Area a sweep of the medals.

Michael was essentially a self-taught fencing master. Like many at that time, he was awarded the title of Fencing Master by the USFCA based on results rather than graduation from a program. His training with Csaba Elthes was the model for his teaching style and his focus on superior technique was definitely in line with that Hungarian approach. However, Michael was a great consumer of new ideas and studied a wide variety of ideas, techniques and methodologies, finding ways to incorporate what were then pretty radical ideas into his training. He encouraged his fencers to work with a San Jose State-based sports psychologist, Tom Tutko, who was one of the first major researchers in the field and writer of numerous books on the subject. Gay, Vinnie and Stacey, along with another teammate they recruited to join them in San Jose, Hope Konecny, worked the Tutko to develop a winning mindset. That work, along with the types of books Michael would recommend, like Musashi’s Book of Five Rings and Herrigel’s Zen and the Art of Archery, added to the mental aspects of training Michael mixed with the physically challenging training regimen he put them through. As Vinnie put it, they were physically strong, well trained, young, confident and somewhat brash. They intimidated a lot of opponents.

Hope Konecny and Iza Farkas were two East Coast fencers that made the trek to San Jose to train with Michael alongside Gay, Vinnie and Stacey.

Vinnie Bradford: “I think I’m most proud of the things that we did at San Jose State. We were the first women’s collegiate team to win a national championships. We were the first women’s team to win four national collegiate championships in a row. And I don’t think anyone’s done that. We also took the individual title four years in a row. I’m not sure any other college has done that.”

Michael was very protective of the women in his program. They got a lot of attention when they went to competitions and he did his best to mitigate that. But winning begets winning and the program continued to build.

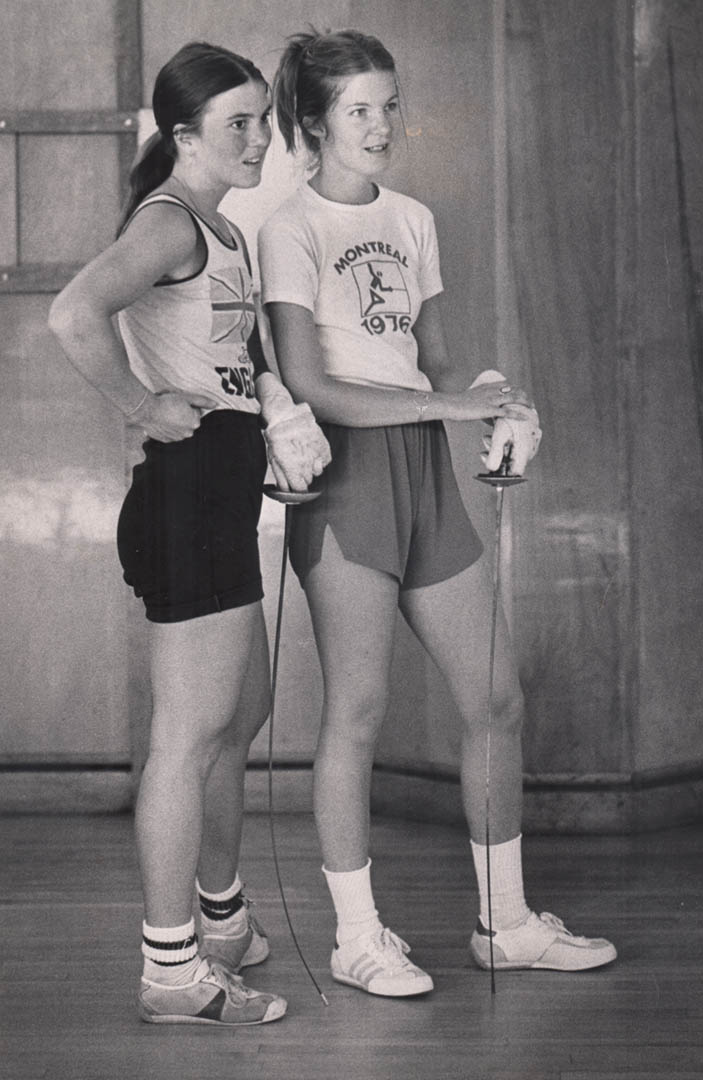

Hope Konecny and Stacey Johnson in the salle at San Jose State.

Stacy Johnson: “Michael, with his force of personality, was able to ‘hold the space’. And within that space, allow great creativity and personal evolution for all these others. You have to have a capacity for leadership to do that. He had the ability to hold that space for all of us.”

None of this likely happens without the benefit of the implementation of Title IX, which, thank you wikipedia, is defined thusly: Title IX of the Education Amendments Act of 1972 is a federal law that states: “No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.” Colleges and Universities all over the country had to make sure that women had access to the same athletic opportunities as men. That doesn’t mean they needed to field a women’s football team, but they did have to provide opportunities in women’s athletics that in some fashion mirrored the offerings for the men. Smaller sports like fencing were the beneficiaries of this and for years Michael’s Spartan fencing program brought a great deal of hardware and awards to show off at the Athletic Department’s annual awards presentation.

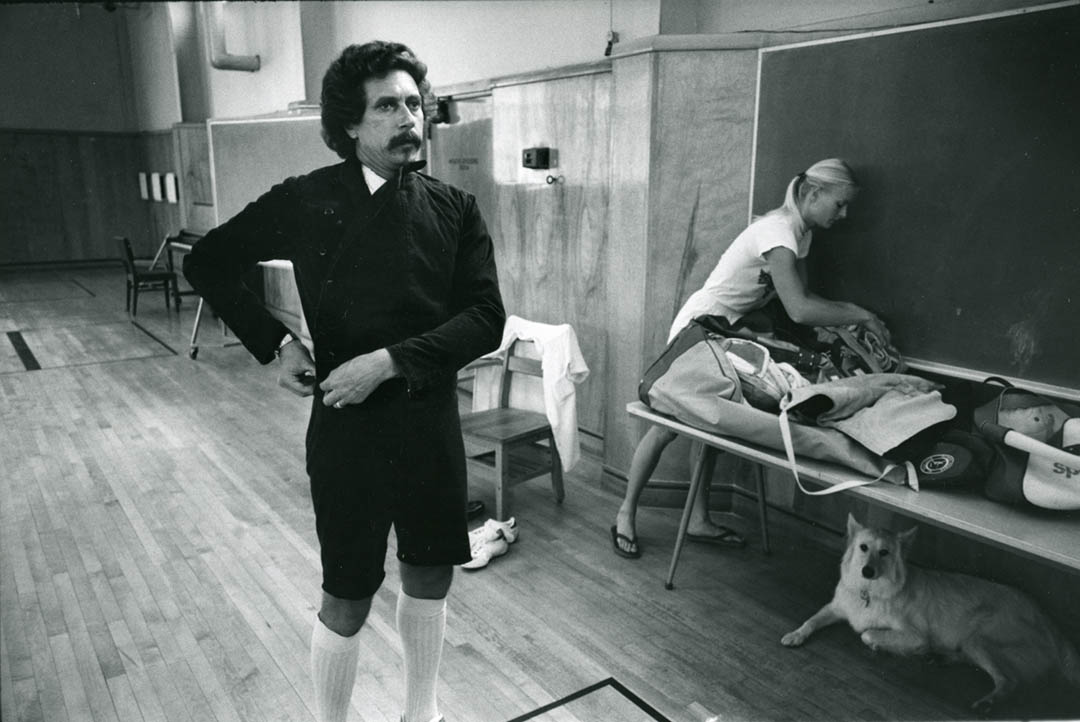

Michael and Gay preparing for a lesson while Honey, Gay’s dog, sits under the table and seems to say, “Well, just another day at the office.”. Honey was just the nicest dog, knew everybody that came through the salle and had tremendous patience for the crazy game her humans played.

When I arrived at San Jose, Gay, Vinnie, Stacey and Hope had all completed their eligibility and handed off the reins of the women’s team to Joy Ellingson, Diane Knoblach, Laurel Clark and others. They continued to train in San Jose until the 1980 Olympic team selection was through. After those not-games for American athletes, Gay retired from competition, as did Stacey, who went back to Texas and continued her education, pursuing advanced degrees. Vinnie also moved back home, training for several years with the pentathletes in San Antonio. Hope became an artist, returning to her East Coast roots. But for a brief few months, I was able to watch, learn and fence a little with this powerful group of athletes. They certainly set a standard of excellence all of us attempted to emulate.

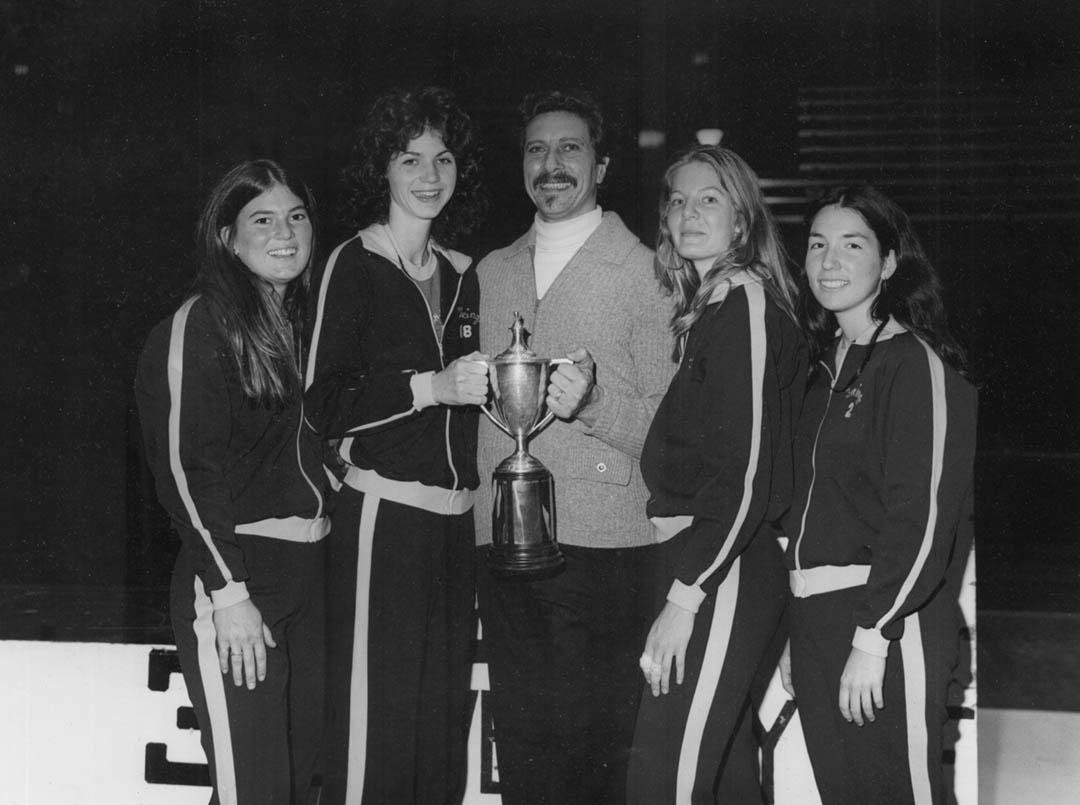

Hope, Vinnie, Michael, Stacey and Sharon Roper with the last of the Vinnie/Stacey-anchored group’s team trophy in 1978.

There were not many programs like this. Were there any? For this brief period of time, it may well have been unique. It attracted top level recruits and produced phenomenal results under the tutelage of a non-conformist coach who had a unique vision and was able to instill his passion for this sport in a highly diverse group of dedicated fencers. I say dedicated because if you weren’t you didn’t stay. The program demanded most of your attention. I’ll let Stacey Johnson have the last words on the matter:

Michael elevated everything. He elevated the game. He elevated the consciousness. He elevated the art. He elevated our thinking about the art through study. He was incredibly supportive of education and knowing, too, that I do not believe that any champion can be not smart. Fencing requires you to have some smarts. And so the bedrock of that is education. So he supported both our educational journey and added to it. The things that he had read and studied and participated in. It was all part of a learning experience.

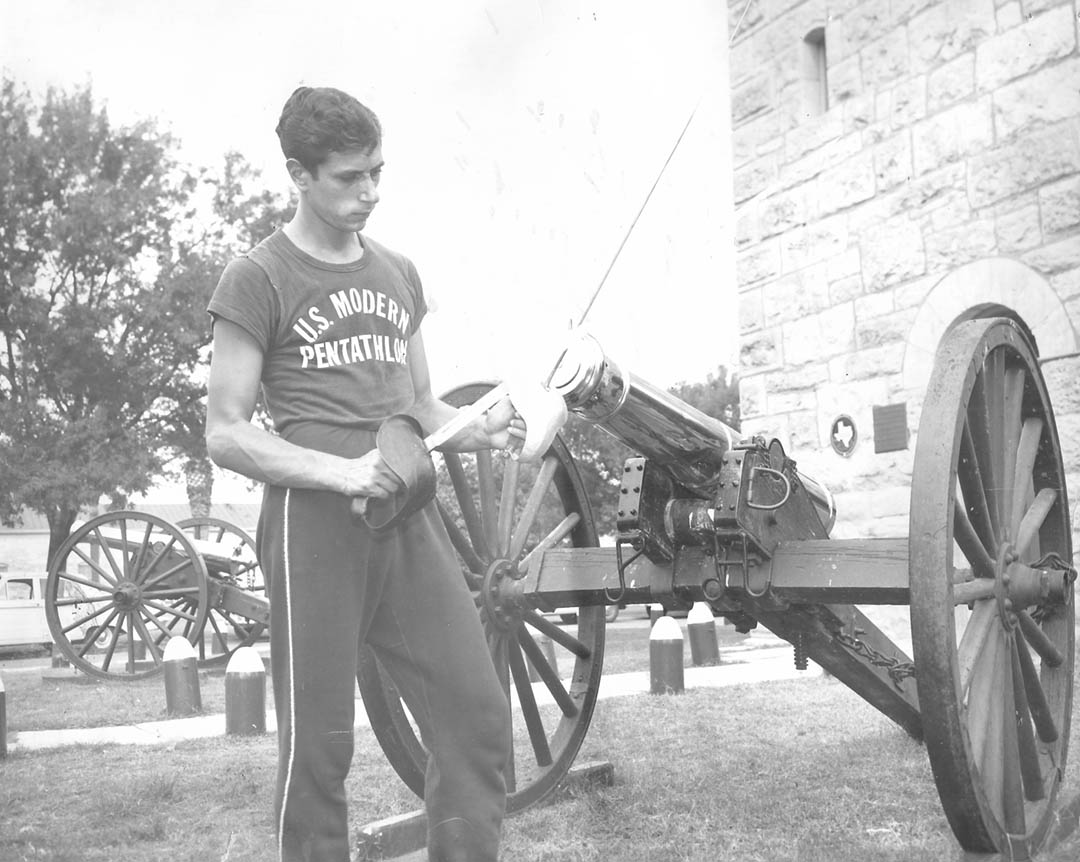

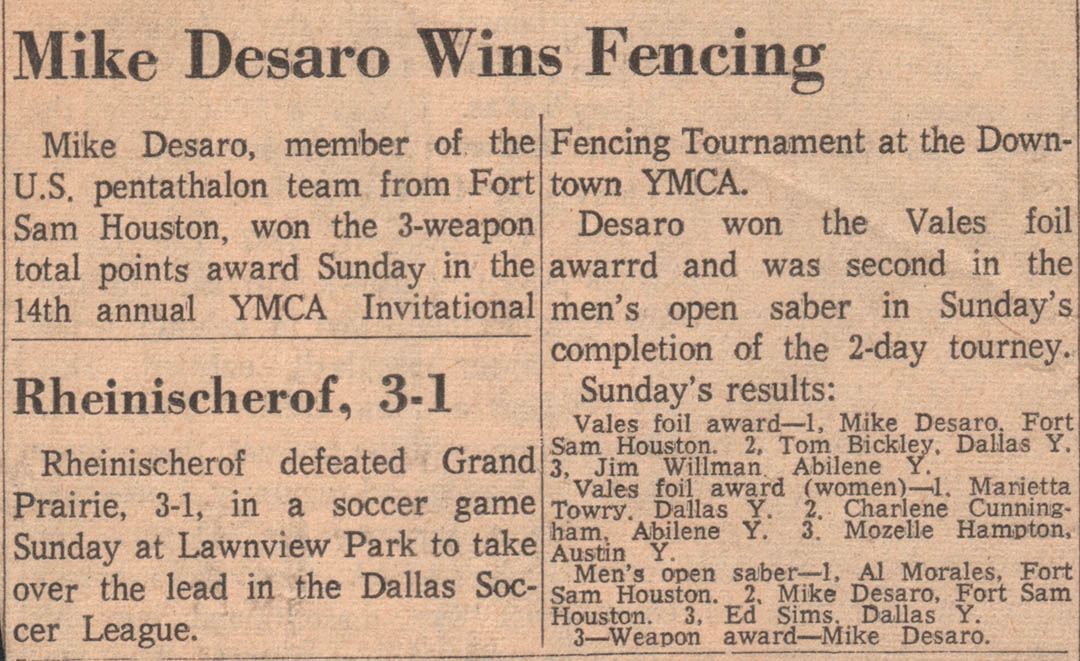

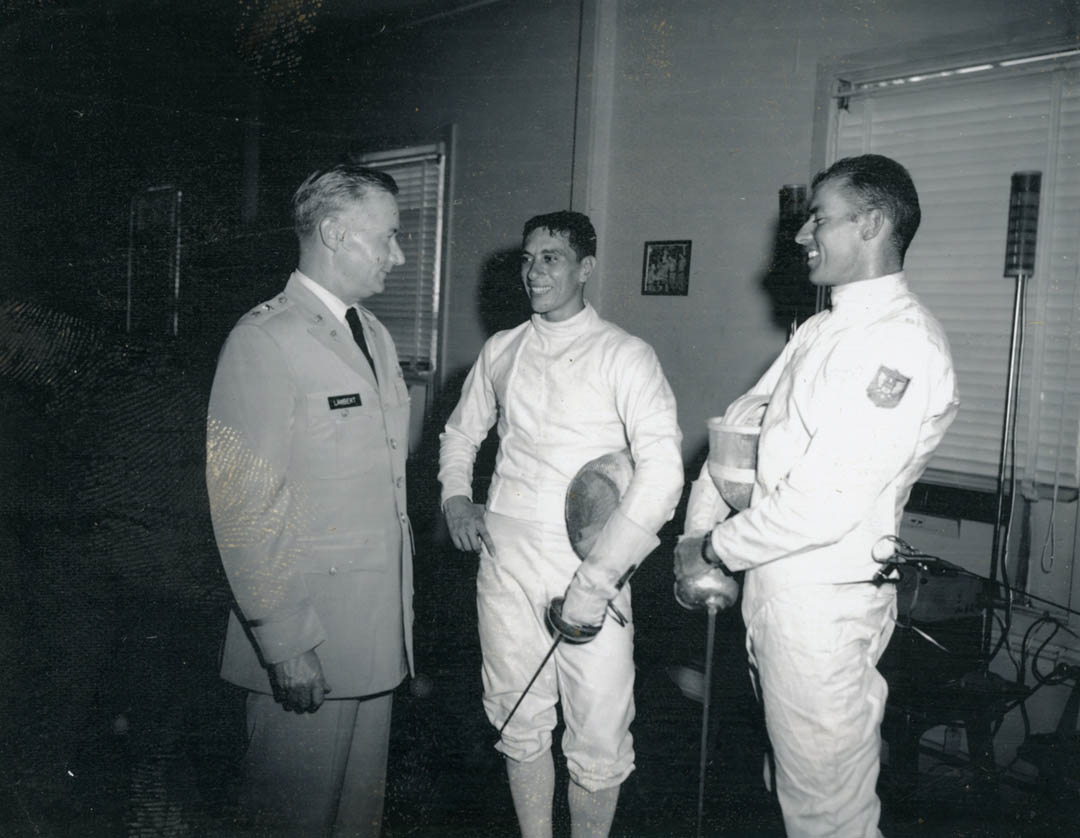

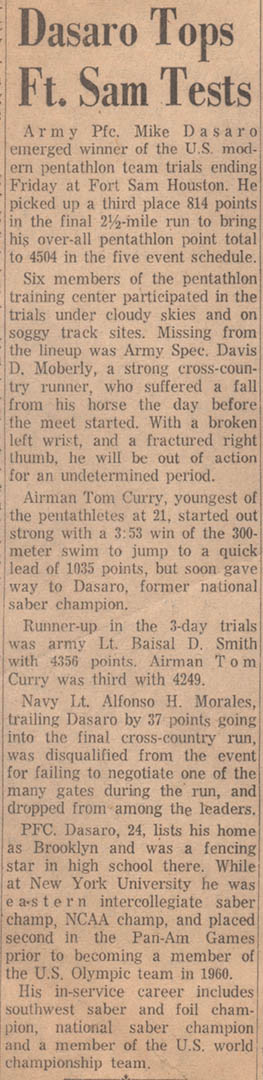

Michael D’Asaro Goes To Texas