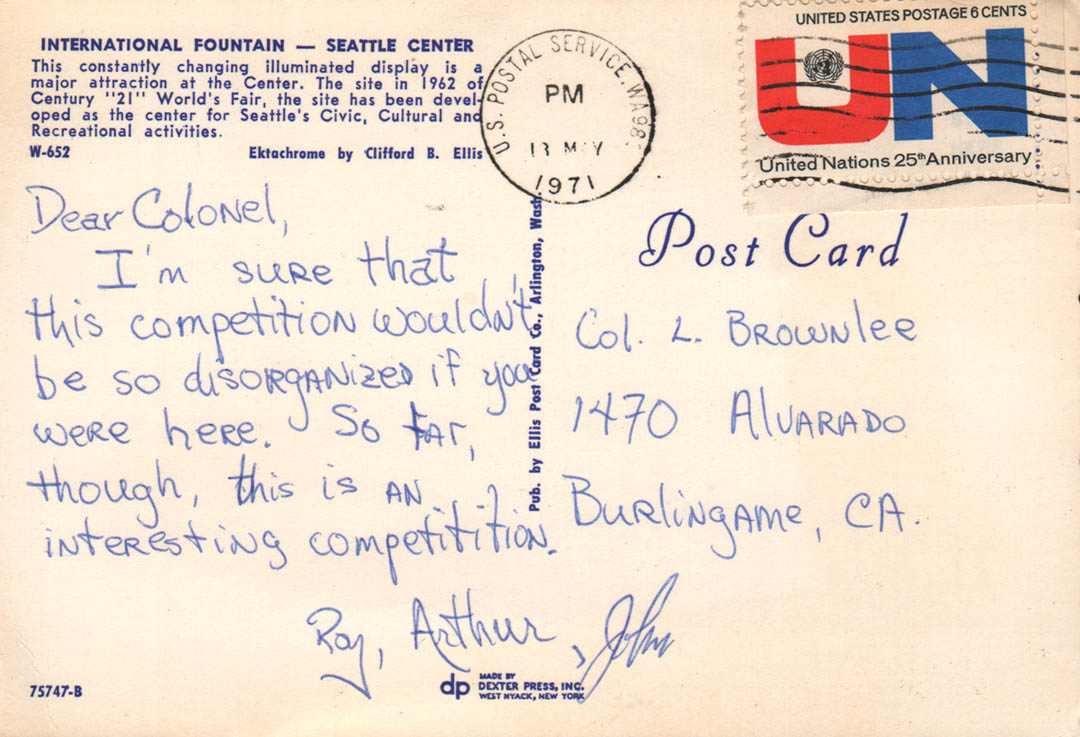

It’s so much fun to have your expectations and assumptions blown to bits. That happened to me this week when I had the great fortune to meet the daughter of long-time Letterman fencer Colonel Laurance Brownlee. Colonel Brownlee was a fixture of West Coast fencing from the mid-50’s until his passing in 1972. As a military Colonel, he had organizational skills that he generously lent to tournaments and fencing events up and down the coast. And, as this post-card from some young Nonomura family members attests, he was good at it.

A 1971 postcard sent by three of the Nonomura lads, Roy, Arthur and John, to Colonel Brownlee during their participation in a Seattle tournament.

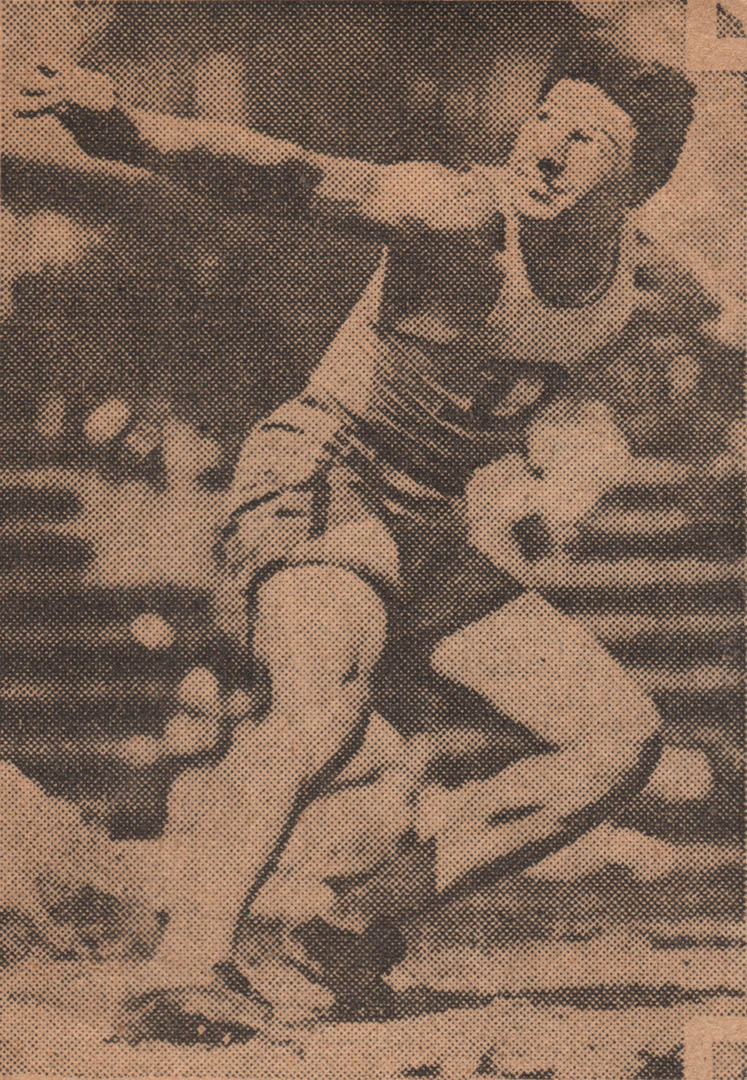

Laurance Brownlee grew up in New York State as an all-around athlete, winning medals and commendations in multiple sport. As part of the material his daughter donated to The Archive, I found several news clippings from his Washington DC prep school days and even a couple of medals, one for javelin and one for discus. He also starred on the football team, fenced and played lacrosse.

Prep school athlete Laurance Brownlee scores a 153′ 11.5″ javelin throw.

Accepted to the United States Military Academy after high school, he opted to wait a year before attending. His younger brother was accepted into Annapolis and the two wanted to go through the two academies at the same time. At West Point, Laurance fenced all four years, competing for the team and lettering. He graduated with the class of 1929, a newly minted 2nd Lieutenant.

Post-graduate photo, taken in 1929.

I have a ton of information about his military career that I still need to parse, so I’ll just hit some of the high points that stood out. He was appointed to the artillery corps, spent time in Panama, then taught French at West Point and spent part of 1937 in France to advance his skills. He was assigned to the Pacific Theater during WW2. He saw duty as Commanding Officer of an anti-aircraft artillery brigade. After that war, he continued to serve and was awarded a special commendation for his management of a ceremony to return the remains of American soldiers killed in the Philippines. He also spent time in Korea during that conflict and was awarded a special service medal by the Korean Army. One thread that I was able to follow was his letter writing campaign to be allowed to wear the Korean medal. What I learned was that awards by other nations’ militaries can only be worn by American soldiers with approval from their service branch. Brownlee’s request to wear the medal was initially rejected by the Army, although they admitted that the medal was pretty significant and fully earned by Brownlee’s work with his Korean counterparts. When he persisted, his request was forwarded to Congress, who had the ultimate authority to grant or deny his request. I haven’t yet found anything that indicates the final decision. However, there are two different letters from Korean officers who, post-war, sent Brownlee letters thanking him for his efforts during the war, and in one the writer gave his schedule for a trip to the US in the hope he would be able to meet up with the Colonel while in San Francisco.

He was stationed at the San Francisco Presidio when it was an Army base and his family lived down the Peninsula in Burlingame. Somewhere along the line during his time at the Presidio, he met William O’Brien, a civilian records administrator for the base, who founded the Letterman Fencers Club in one of the on-site gymnasiums. Colonel Brownlee represented Letterman as a competitor from that moment until he stopped fencing shortly before his death in 1972 at the age of 66 from cancer. One of his between-war Army assignments was Roswell, New Mexico and he spent a fair bit of time around Alamagordo and the nuclear testing facility. Like many servicemen who spent time around the US nuclear test sites in the late 40’s, early 50’s, he died of cancer. Coincidence?

Left to right, Tommy Angell, Shirley Canter, Mary Huddleson and Laurance Brownleee at the 1955 Letterman Invitational. Tommy gets the presentation from the Colonel.

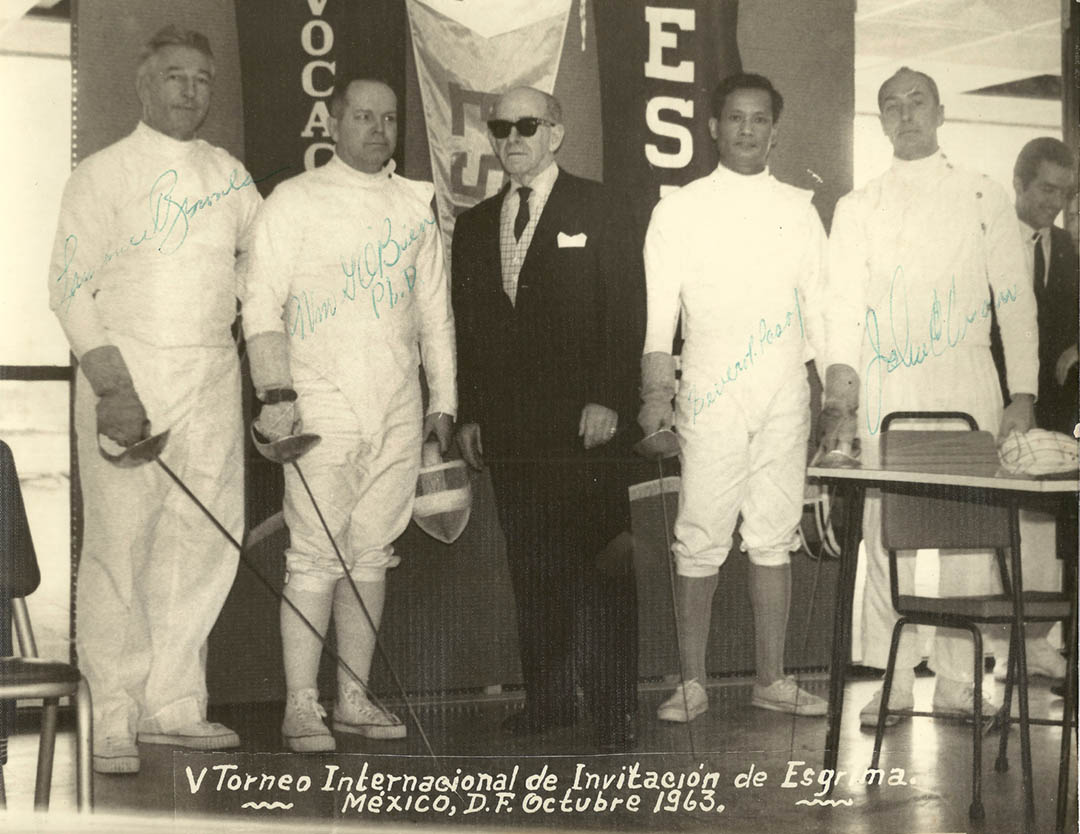

In the late 50s and early 60s, there was an International meet held for a number of years in Mexico City. Brownlee, fluent in Spanish as well as French, helped out with arranging teams of San Francisco fencers to go down to compete. Bill O’Brien and Hans Halberstadt would attend – Bill to coach and fence, Hans to, well, just be Hans. All the pictures of him in Mexico show him in a suit, so I don’t think he dispensed much coaching other than a suggestion or two.

Brownlee used his time wisely, it seems. In the collected material there is an envelope with a number of artifacts from his travels, including a ticket stub for the National Museum and another for a bullfight. The best thing about perusing the records of a retired Army Colonel seems to be that everything is meticulously sorted and stored.

Left to right, Brownlee, William O’Brien, Hans Halberstadt, Severo Pasol and one of the competitors from Mexico who’s name isn’t legible, from the 1963 edition of the Torneo Internacional de Invitacion. Pasol won the individual foil in 1962. I have the program from 1963 that records several years of results, but not the 1963 results. Other 1962 winners include Maxine Mitchell, Alfonso Morales (sabre) and “Miky” D’Asaro (epee). Other participating teams besides Letterman included several Mexican clubs, Panama’s national team, the Dallas Fencing Club and the US Modern Pentathlon team, of which D’Asaro and Morales were both members.

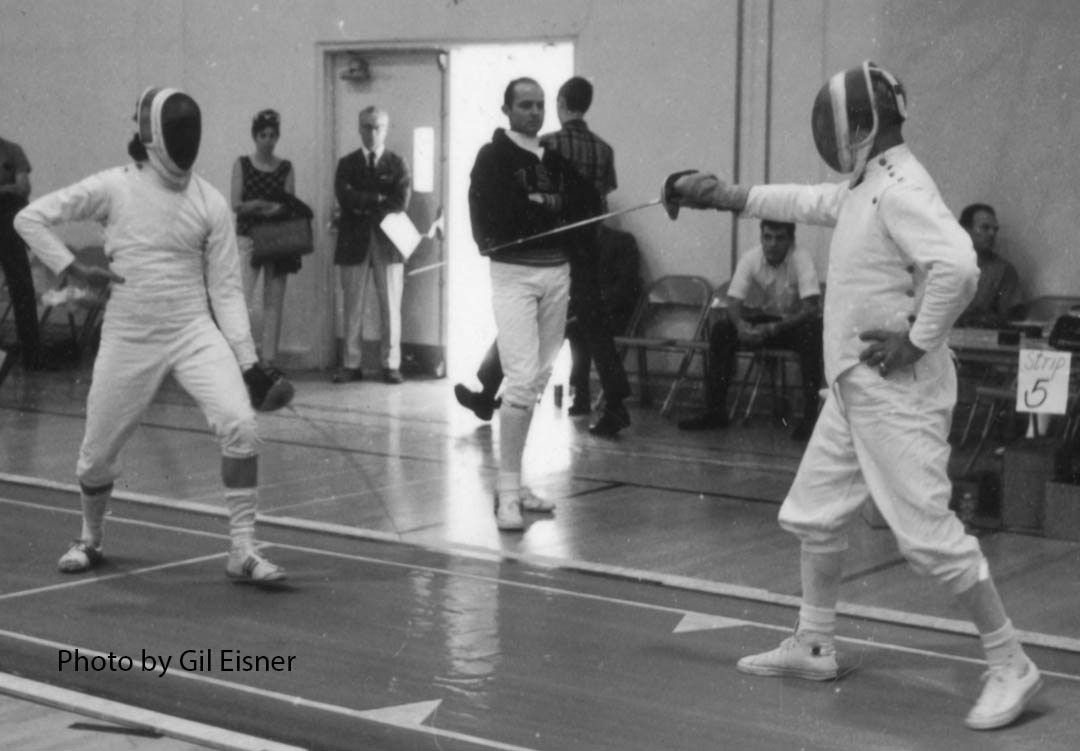

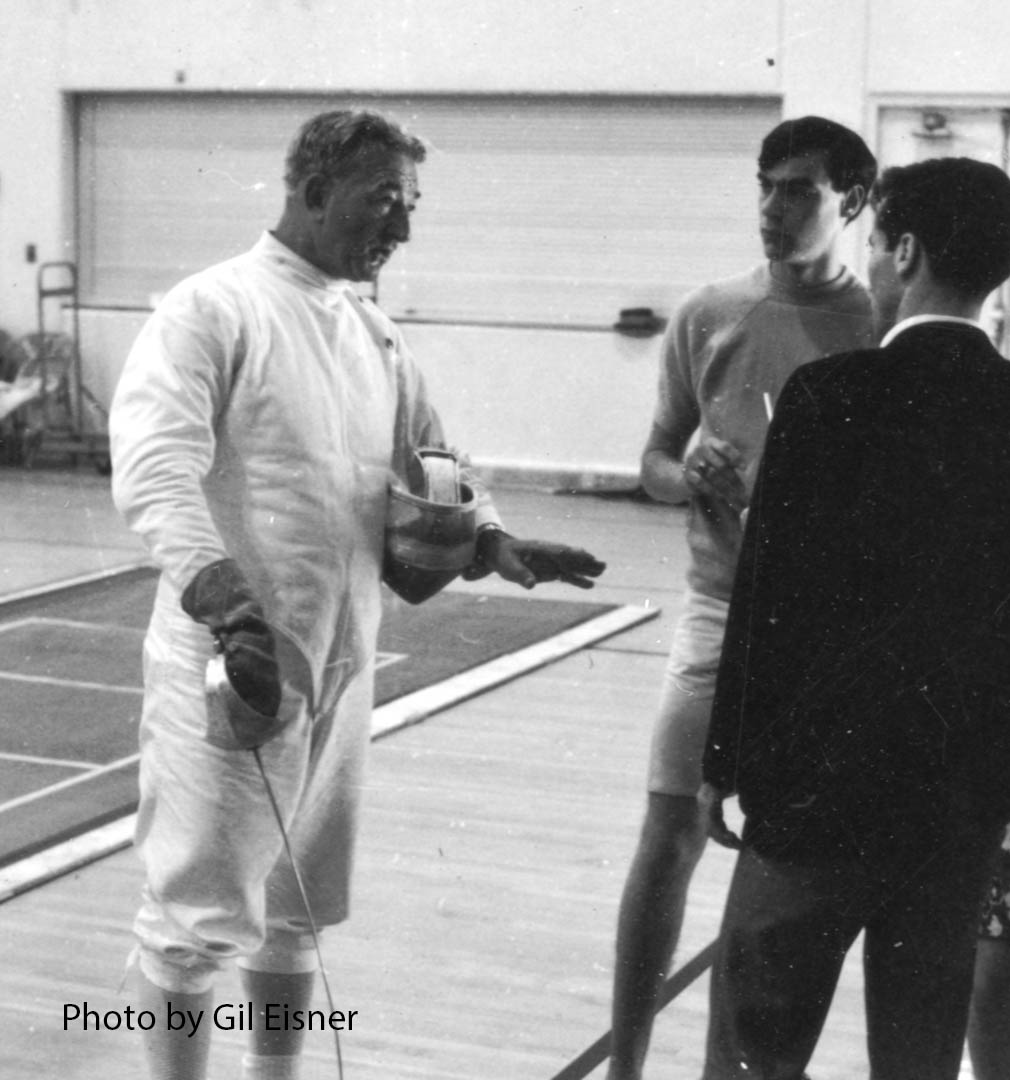

I’ve been digging through the box of medals that was donated by the family and found that he won a ton of medals. That’s one of the reasons that my expectations of him were so off. While I knew he had fenced a long time, so many of the pictures I’d seen of him seemed to show an older, slightly overweight guy in a suit and tie, seldom in fencing garb. As an older, slightly overweight guy myself, I know what category that puts me in, and by the time Brownlee began fencing in the Bay Area, he was in his late 40s. How many medals could he have won (was my thinking)? Well, a bunch. He fenced at twenty US National Championships, which leads me to a particular story that I long believed to be apocryphal, but seems to have actually taken place. Maybe more than once. While researching the subject of Michael D’Asaro, the lead character in my still-in-production second documentary feature (Greg Lynch, Co-Producer and Editor), one story told of Michael was that he had, during a major competition, upon the command “fence!” tossed his sabre from his left had to his right and chased his opponent off their end of the strip while waving only his gloved hand at said opponent. It seems we have pictures of the bout, and the victim of this prank was none other than Laurance Brownlee. It took place during the 1967 US Nationals in Los Angeles, Michael’s last before become a fencing coach. Gil Eisner, All-American and US National epee champ in 1962, captured some of the action on film.

Michael D’Asaro on the left, Laurance Brownlee on the right during the Individual Sabre at the 1967 Nationals. No photo of the actual no-sabre-chase exists to my knowledge.

Post-bout, Colonel Brownlee likely had something to say to the officiating team. Michael was undoubtedly the superior sabre fencer, but whether this event stemmed from anything between the two or was simply an impish joke on Michael’s part is unknown.

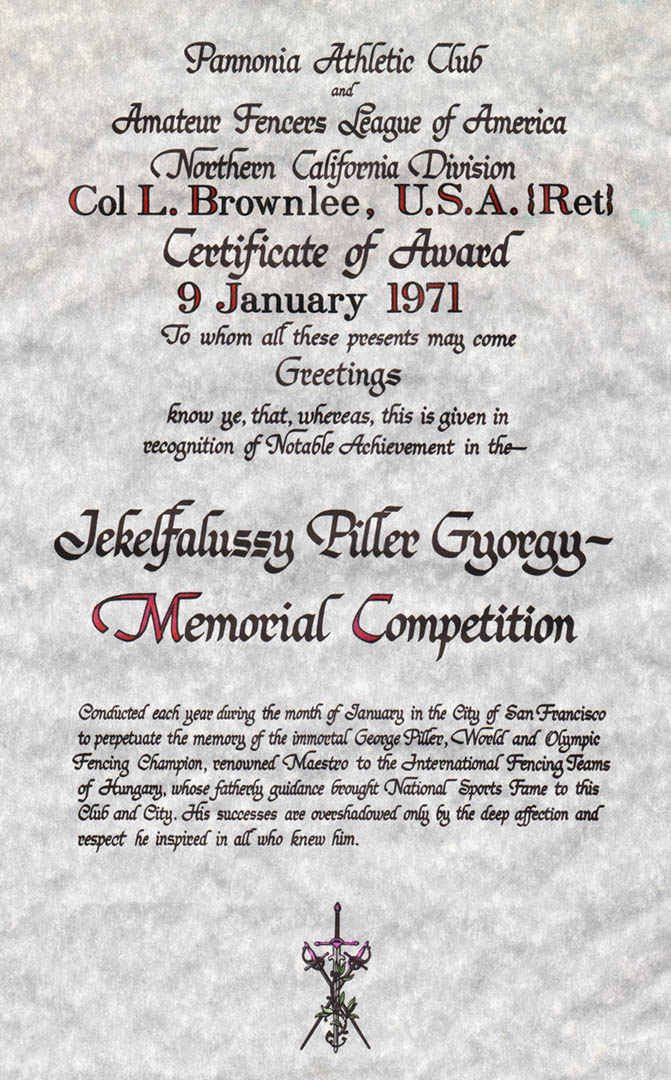

One item in the collection is a completely unique version of a document I’ve seen many times, and earned myself. The Pannonia Athletic Club sponsored the Piller Memorial competition annually from 1961 until the closing of the club. As finalists, you would compete for the wonderful bronze medal with Piller’s profile which was usually only awarded to 1st place, but sometimes to the top 3. Additionally, there was a parchment sheet that would go to all the finalists as a Certificate of Award that announced your achievement at the memorial competition and included a brief bio of Piller. But I’ve never seen one like this:

The Piller Memorial Certificate. Two things have been added to this beyond the standard issue: Brownlee’s name, and the date. And the color. Three things.

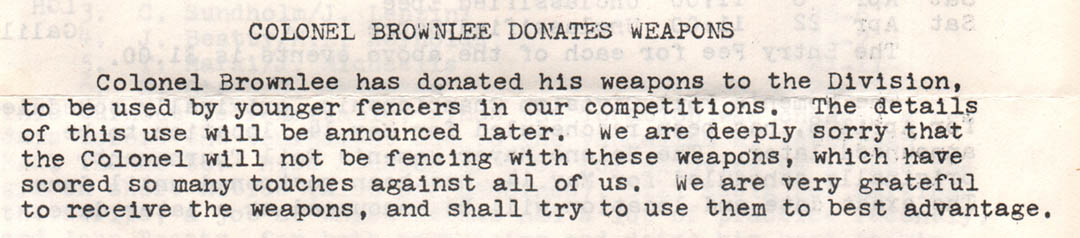

The date of the above is 1971, the year prior to Brownlee’s death. He battled his cancer for several years and continued to fence as long as possible. When he finally had to stop, he donated his weapons to the benefit of young fencers in the Nor Cal division. Of the many organizational positions he held for the good of the sport, one was Chairman of the Junior Olympic Program, so developing youngsters in the sport was clearly of importance to him.

In reading through all the material about Brownlee’s fencing life, and skimming over his accomplishments as an officer, husband and father, I’m struck by how much this man was deserving of the respect shown to him by his peers during his lifetime. This was clearly a man to go to war with, either literally or in the fencing-teammate figural sense. His daughter, Sheila, gave me another glimpse into his character, saying he had very definite ideas about the importance of expanding one’s horizons and perceptions of the world. “Money”, she said, quoting her father “was for education and travel.” I’ll end by quoting part of a lengthy document sent to the Army for use in creating his obituary for the records at West Point. I’m not sure who wrote the below, but it wasn’t the family. More likely someone like Jack Baker or Bill O’Brien.

Colonel Brownlee’s bout with cancer was his ultimate ordeal. Sheer determination and his will to fight carried him through the final years. Typical of his courage, in his final match his right arm, brittle from the infiltration of cancer, fractured; he would not retire from the strip, but continued fencing with his left hand. A the conclusion of the bout, he collapsed from pain. His last fight had ended.

The Northern California Division, in recognition of Colonel Brownlee’s dedicated service and indomitable courage, has established the Iron Man Trophy in his honor.

It is a fitting tribute to this great gentleman to pause a moment and reflect: His kind shall not pass this way again.

That. Right there. Respect.

Interesting to read things about my grandfather that I hadn’t known. From what I remember, he trained for the Olympics in 1932, and was ‘eliminated in the quarter finals’. I mever knew if those quarter finals would have put him on the team, or if he was already on it and eliminated during the Olympic competitions. When he taught me the basics, we trained both left and right handed. He was also a collector of ancient weapons, from European medieval weapons to Phillipine fishing bows.

His kind will, and I hope are, passing this way right now. Sadly, these honorable people tend to be easier to recognize after they’ve died. Como los santos.

The US National Championships during an Olympic year was the event where you had to excel to be selected to an Olympic team. Making the finals was an imperative to have a chance. So with a quarter final finish, he would have missed out. I’ve really enjoyed getting a chance to know your grandfather’s history. He was a fascinating man.