In going about my daily Archiving routine, I’m beginning to recognize that small obsessions can take over my focus. Sometimes for days, sometimes longer. Not that they’re out of line with my uber-goals, but they can cause me to veer off topic. Henri J. Uyttenhove is one such obsession. That his history continues to intertwine with that of Harry Maloney, longtime coach at Stanford of fencing, soccer, boxing, rugby and a couple other sports, simply adds to the enjoyment.

Uyttenhove came to this country from his native Belgium to Pasadena, CA, at the behest of a local SoCal amateur, Arthur Jerome Eddy (that’s as much as I know about Eddy) and, interestingly, “…the Belgian master came west, he accompanying Harry Maloney, the Southern California professional champion.” Maloney was 31 when that was written in 1907 in the LA Times and the following year he went north to Stanford. Uyttenhove stayed in SoCal, teaching at his own private salle in Pasadena, the Pasadena Athletic Club, the Los Angeles Athletic Club, the Hollywood Athletic Club and USC. UCLA may have been in there for a brief time, as well.

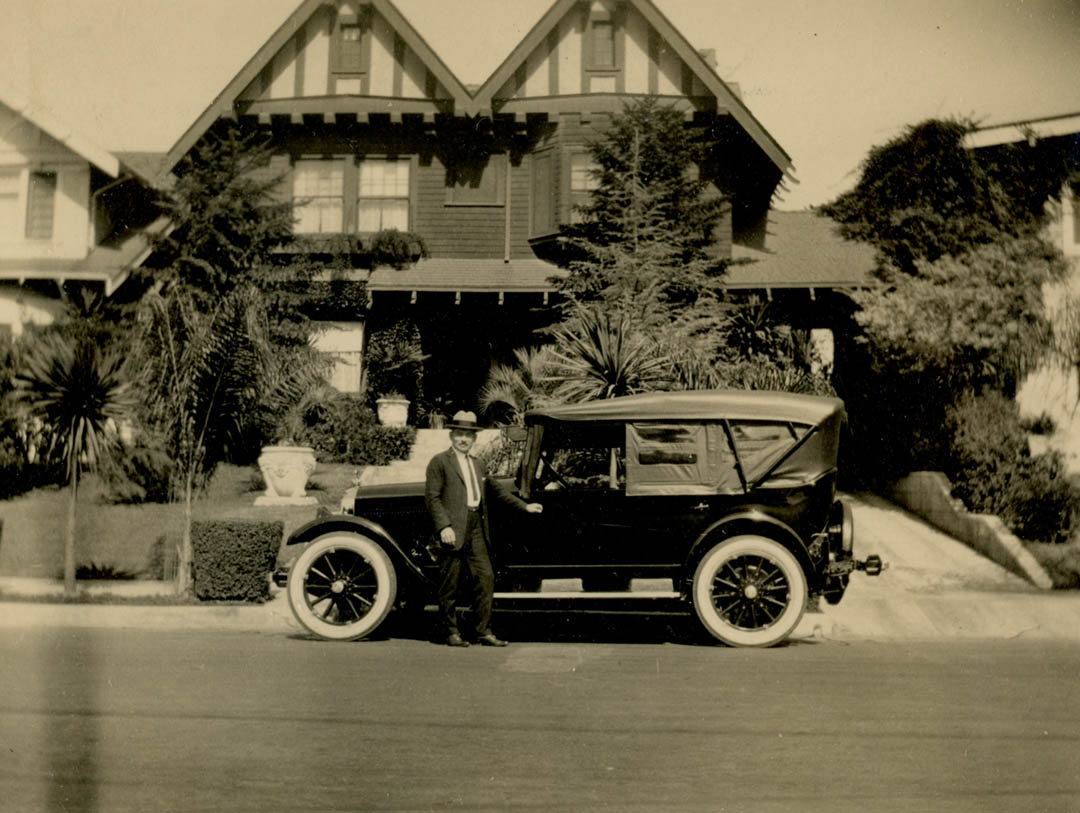

This must be how he got around town so effectively. This photo is from the scrapbook of Muriel Bower and shows Uyttenhove and (presumably) his car. No date or other information, although I wouldn’t be surprised to learn that this house is in Pasadena. That’s the town where Uyttenhove settled when he arrived from Belgium. Anyone able to identify the year on the car?

But here’s where the fun begins. Last year The Archive was the beneficiary of a donation of material from Kevin Murakoshi. He had made an Ebay purchase at some point and came into the possession of a cache of papers and books related to John McKee, long-time fencing master at The Cavaliers club in SoCal. Kevin was kind enough to pass this material on to The Archive. While perusing these papers back in September, I came across a reference to something I’d never heard of before. McKee had put together a list of fencing books in his “Fencer’s Manual”, a book he prepared for publication in 1978. (It wasn’t ever published.) One of the listed books was “Foil Fencing” by H. J. Uyttenhove, along with the date, 1937, and this additional tidbit: “Published by the University of Southern California Athletic Department”. Armed with this bit of information, I spent a good hour Googling that string of information in various ways to see if I could land on a reference to the book. Nothing in Google, nothing on AbeBooks, Amazon, pick a website – I probably looked there. Just nothing.

Figuring I had nothing to lose, I sent an email off to the USC Libraries (note the plural) to see if they had any info. No such luck. They actually checked the WorldCat (which I hadn’t thought of) and didn’t find a reference. That’s likely to mean it wasn’t ever published in a form that would get it a Library of Congress entry, which, while informative, means it’s even less likely that it was put together in such a way as to survive to the present day. The very nice and patient people at USC Libraries did mention that their interconnected library system didn’t have much from the USC Athletic Department and they might well have their own stash of things that hadn’t been entered in their system. Or any system. I tried that recommendation only to hit a dead end. If USC maintains an Athletic Department library where old books might be stashed in a corner and forgotten, I couldn’t find anyone that could point me to a librarian for it, or even a student intern with nothing better to do than peek into some dusty corners. And so, nothing.

My December visit with Muriel Bower revived the memory of trying to find the book. (I’ve been going back through my notes – I haven’t yet transcribed the recording of our conversation – trying to piece together where I ran across another reference to Uyttenhove’s book. But I did.) Armed with a little bit more info, I sent another email off to USC, this time to a Sports Information person. The additional information I’d picked up was that there was an additional subtitle for the book, “A Syllabus for Physical Education”. Again, very pleasant response from USC, but again, never heard of it. With nothing from USC to hold onto, I figured that was the end of it.

Until last week. Early in the week, I got a text from Andy Boyd, the son of Olympian (36 & 48), LAAC fencer and Uyttenhove student Andrew Boyd. (Read about my visit with the Boyds here.) “Mailed you something today. Hope you enjoy it.” A few days later a package arrives. Guess what’s in it?

You can’t make this stuff up.

It really IS the book I’ve been looking for. Seriously, this is so very cool. The book is 42 pages long and the cover has the pencilled number “55” in the upper right hand corner. I’m guessing copy #55 of however many. It’s bound by stapes and the staples are covered very neatly with a binding tape of some kind. The pages themselves may well be typed. There is a hint of ink bleed on the back of each page, the whole thing being single sided, and it doesn’t have that pre-xerox mimeograph look. Still, even if I’m not entirely sure how it was printed, I’m guessing there were once a fair number of copies. Did every fencer get one of these to take home? Or did they collect them at the end of every semester? It’s not surprising either way that Andrew Boyd would have his own copy, as Uyttenhove didn’t train many Olympians. No doubt it was a gift to Boyd. “Hey, I wrote a book! Here’s a copy for you. Ok, back to work…”

The book, like many fencing books, spells out the pertinent terms that need to be defined for the students and lays out the lesson plans for a course of study in 10 sessions. The final lesson, learning the Grand Salute, has a nicely detailed description of that now seldom seen bit of performance art. What I was hoping for during my search for this volume was that it would have some amount of introduction or storytelling that would give me a sense of Uyttenhove’s character or thinking. That’s one of the great benefits of Aldo Nadi’s “On Fencing”. You get a fair sense of the author through his use of language, as he writes enough material that isn’t “…put your hand here, hit the target there…” so the reader can get a little way inside Nadi’s head. Of that kind of writing, this book is sadly lacking – at least, I’d hoped for more. Since, as the title states, it was written as a syllabus for a college course of instruction, I can’t be terribly surprised. Still, what he has written in the Introduction does provide a bit of glimpse into his motivations and his personality.

This is the opening paragraph of the Introduction. He follows up with a brief note that fencing in the United States is becoming more popular in colleges and universities, as well as mentioning that in the East, high schools are also beginning to offer fencing as a course of instruction. As in, “Hey Westerners! More fencing sooner!” 83 years later, we’re finally getting kids into fencing, even as the University system continues to shutter programs. Why can’t we have both? A topic for another time, I suppose.

The introduction continues with 9 objectives for the student to accomplish over the course of instruction. These cover two pages, so here’s the first five reasons:

“…a perfect co-ordination of mind and body.” Clearly, I’ve been doing it wrong these past 40 years. Ah well.

I love these. I particularly like #2: “One acquires a knowledge of the art of fencing through instruction, and in a bout, this knowledge is applied in a contest of skill and ability.” Such a simple description in a single sentence, yet it encapsulates the experience so precisely. It works whether your instruction is sufficient, or if your ability is limited. Whatever your base state, that’s it in a nutshell. I also like this: “Fencing is a distinctively individual sport, and thus each fencer shoulders his own responsibility.” I played only team sports growing up. Fencing was my first individual sport and I started at 18. There was, for me, a surprising learning curve in adjusting to the lack of assistance from teammates during a fencing bout. And really, is there any other endeavor that I can as readily point to as having challenged me to ‘use my native capacities to the maximum’? Ok, well, there’s probably a few things other than fencing. But it’s definitely on the list.

Here are the last four of the nine reasons:

He nicely brings in the notion that the sport is fit for both men and women, even if the idea that it is ‘exempt from the danger of bodily harm’ may be stretching the truth, particularly in the 1930s when there was more than one incident of bodily harm on report related to the sport. It isn’t a regular feature of the sport though, and even less so today, so I’ll let it go.

The last one really has the most powerful message for me, and it certainly calls to mind our present day. It’s worth repeating:

Fencing encourages a willingness to participate in individual and group activities, imparts a tolerance toward others regardless of race, and stimulates a high regard for the religious and political beliefs of all people.

Henri J. Uyttenhove, ladies and gentlemen. That sentiment, more than anything, I think provides an insight into the nature of the man we’re looking at. Tolerance, and a high regard for others. Those are two ideas I can embrace.

After these introductory pages, it proceeds to the actual day-to-day instruction for a beginning foil class. He writes in a very concise style and describes things quite nicely. You could probably use the same instruction today over a ten week intro course and not have to do much revision for today’s fencing. He knew his material – after completing his fencing master’s certificate in Belgium, he ran the military’s fencing master program for a few years prior to coming to California. So he was well versed in pedagogy. And, like Nadi, he’s perfectly comfortable writing in English.

There is another Uyttenhove story lingering in my to-do box, but it will have to wait for another time. But this story today, complete with surprising coincidence and insight into a man I could never have met, will be as far as we go today. I’ll end with this photo with Uyttenhove and his fencers from the University of Southern California, circa 1938.

Doug, as always, I appreciate your doggedness and sleuthing abilities!

Thanks Allen! This one was definitely less sleuthing and more something falling into my lap. But I’ll take it!

Great sleuthing!

Thanks Eric!