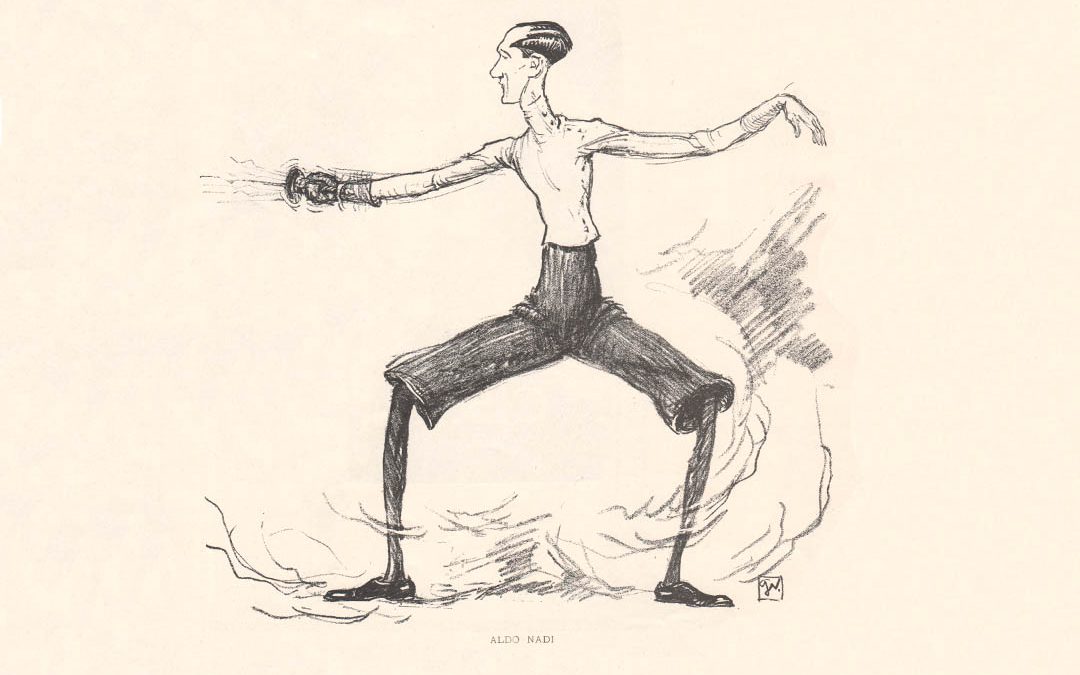

If I don’t write something about Aldo Nadi for too long, I get this annoying twitch in my eye that will only begin to calm down with a collection of images and some quality time with my laptop. Buckle up! Some time back, I published a four-part series about a very interesting document that Aldo Nadi typed up and mailed out to an unknown number of recipients that details his personal record of fencing as a professional during the heyday of fencing for dollars. (The copy I have was sent to Hans Halberstadt and came to the Archive thanks to John McDougall.) Actually, since most of these matches seem to have taken place in France, let’s call it “Fencing for Francs”. (You can see the first of the series here.) Nadi’s record as a professional prize-fencer was stellar and he carved up a great number of both French and Italian competitors and masters over the course of about 10 years, with just a few defeats coming at the early stage of his reign. Once he ascended to the top of the heap, he found it harder and harder to find worthy opponents that would take him away from his quality time as a gambler and womanizer. His autobiography, “The Living Sword”, published long after his death, goes into his life choices in some detail. At any event, he left Paris behind and moved to the US in 1935 to begin life as a fencing master, providing a few exhibition matches just to show the Americans why he should be their first choice when picking a maestro. Self-effacing Nadi was not. Ever.

All that to bring me to this week’s subject matter. Still living life under NorCal’s version of quarantine, I continue to find more things to document and organize. That puts things in my hands that I haven’t perused for awhile and this time it’s an amazing two volume book published in 1924 by the prolific French illustrator/painter/lithographer/caricaturist Georges Villa (1883-1965) titled “Haut les Masques”. Both volumes feature caricatures of the great fencers from around the world circa 1924. The French are far and away the most featured with the Italians a distant second, but there are, among others, Brits, Belgians, South Americans, Hungarians and a handful of US personages. The caricatures themselves are pretty revealing of personality. Villa was the son of a General and did lots of sporting figure caricatures, not just fencers, but this work seems unique to his output due to its depth and focus on the single topic. One day I’ll have to sit down with Andy Shaw, the brains behind the Museum of American Fencing and the official historian for USA Fencing, to get the low down on the Americans who are featured in this book and do a story about them. Today, though, I thought we’d review all of the opponents that Aldo Nadi mentions in his eleven page document of his time as a professional fencer who also show up as caricatures in “Haut les Masques”. Fun, right? If you just read their names on the page, the individuals don’t spring to life the way they do when looking at these drawings – at least, they do for me. I thought about arranging the subjects in the order that Nadi mentions them in his Record, but I’ve been doing so much file management during my stuck-at-home hours that I can’t help but put them down alphabetically. Am I right? Who’s with me?

I’d better show a picture.

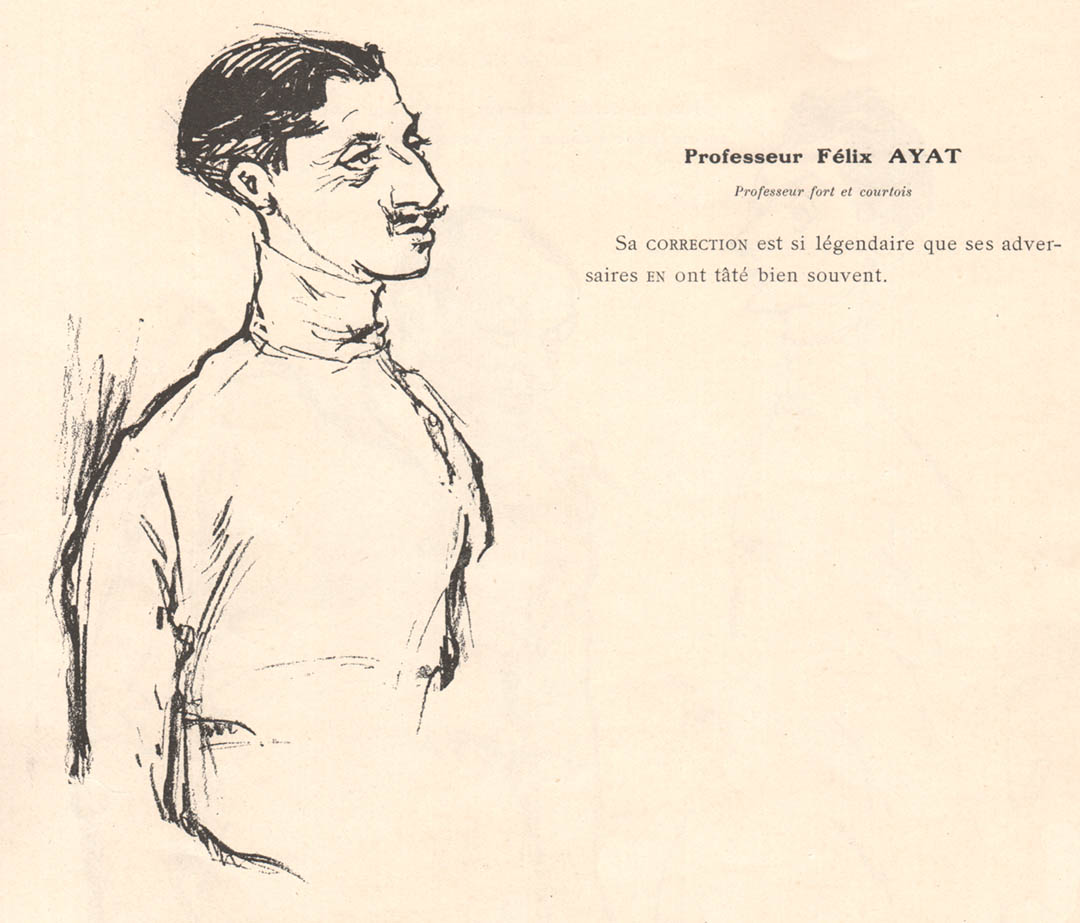

Nadi mentions Felix Ayat in his record as his having been an opponent twice, once in epee, once in foil. For the second meeting, with foils, Nadi says he had to promise Ayat 8 touches or he wouldn’t agree to the match. The final score tally was 14-8 in Nadi’s favor, so Ayat was happy. In their epee match, Nadi was up 7-1 at the rest point. It seems that changing officials wasn’t uncommon during the break in addition to giving the fencers a brief rest. However, it appears that when Lucien Gaudin, lauded and respected by the French and, indeed, fencers everywhere outside of Aldo Nadi’s mind, stepped in to officiate, Nadi tended to lose his mind. He defeated Ayat in epee, but the score evened up a bit. The final score was 14-9, and the clear implication from Nadi is that his opponent was heavily favored by the officiating. More on the Nadi reasoning behind his Gaudin obsession in a bit.

Bonioli doesn’t rate a first name in the book, which isn’t terribly helpful, but I’m going to guess – since Nadi doesn’t provide it either – that this is Paolo Bonioli, professional champion of Italy in 1923. Nadi states that in 1924, the year of his first Italian professional championship, he challenged the previous year’s two-weapon winner, Bonioli, and defeated him in foil and sabre to become the “Absolute Champion”. That’s how they did things in Italy in the mid-20s.

I don’t pretend to understand how Nadi’s professional matches were understood from a competitive point of view. One of the challenges is how to think about a match against an amateur and Olympian like Georges Buchard. Buchard competed at four Olympic Games from 1924 to 1936 and could not have done so if there was a sniff of his being in any way a professional. Lucien Gaudin, also an amateur and Olympian and, famously, a Nadi opponent, always and with great fanfare donated his prize winnings to charity. I have to assume that Buchard did the same, if prize money was forward. Likewise, I assume that if there wasn’t money on the table, Nadi wouldn’t have bothered. Buchard was a two-time Individual Silver medalist in epee at the Olympics and won Gold twice in the team epee events. He also figures in the discussion about Nadi’s perception of Gaudin and I’ll just keep teasing that story until the big reveal a little further on. Apart from the Olympics, Buchard was also a three-time World Champion in epee, so it says a great deal that Nadi both had great respect for him and also defeated him 12-5 in epee. Nadi goes so far as to describe Buchard as, “Unquestionably one of the century’s three greatest swordsmen.” He does not name the others on the list, although you’ve got to assume his own name was at the top of it, with his brother, Nedo, a likely candidate for second. Brothers, after all.

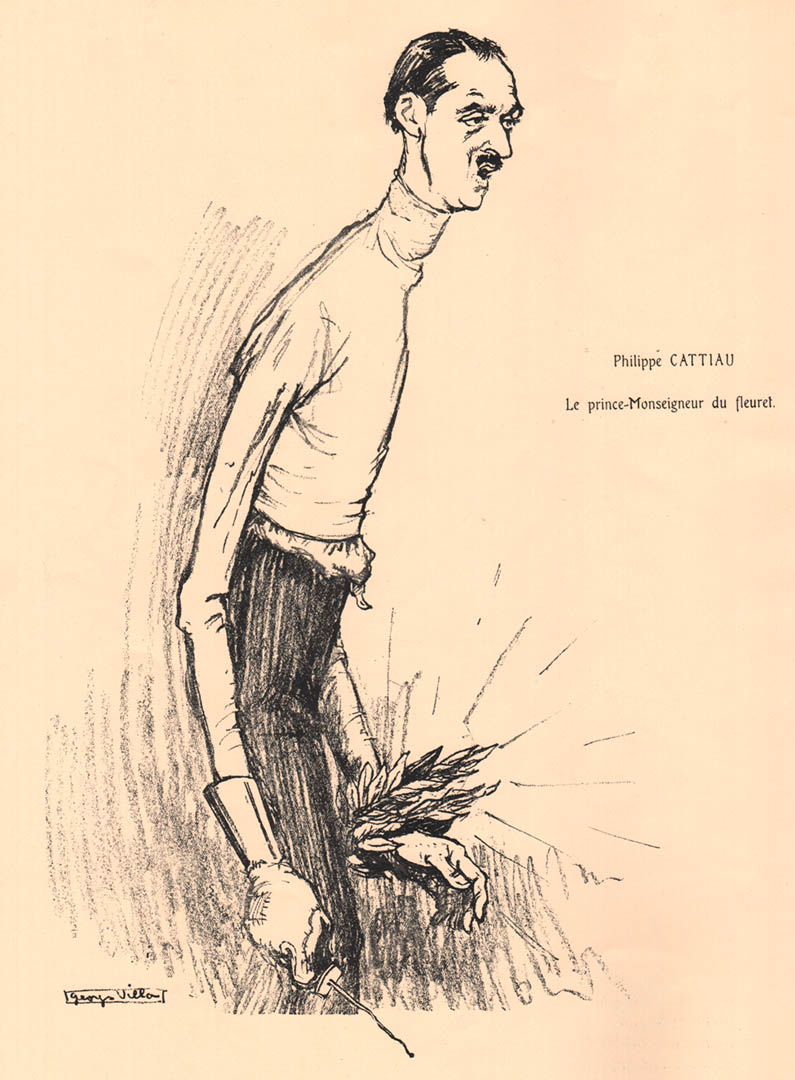

Cattiau was another of the amateurs that put himself in front of Nadi in an ‘exhibition’ match, since Cattiau could not have been motivated by the purse. In his Olympic career, Cattiau competed in five Games, 1920-1936, winning 3 Gold, 3 Silver and a Bronze medal. Two of his Silver medals were in Individual Foil (1920 & 1924) and all the rest were for Team France in both foil and epee. Nadi defeated him in both foil (10-4) and epee (10-6) at a match in Cannes in 1925.

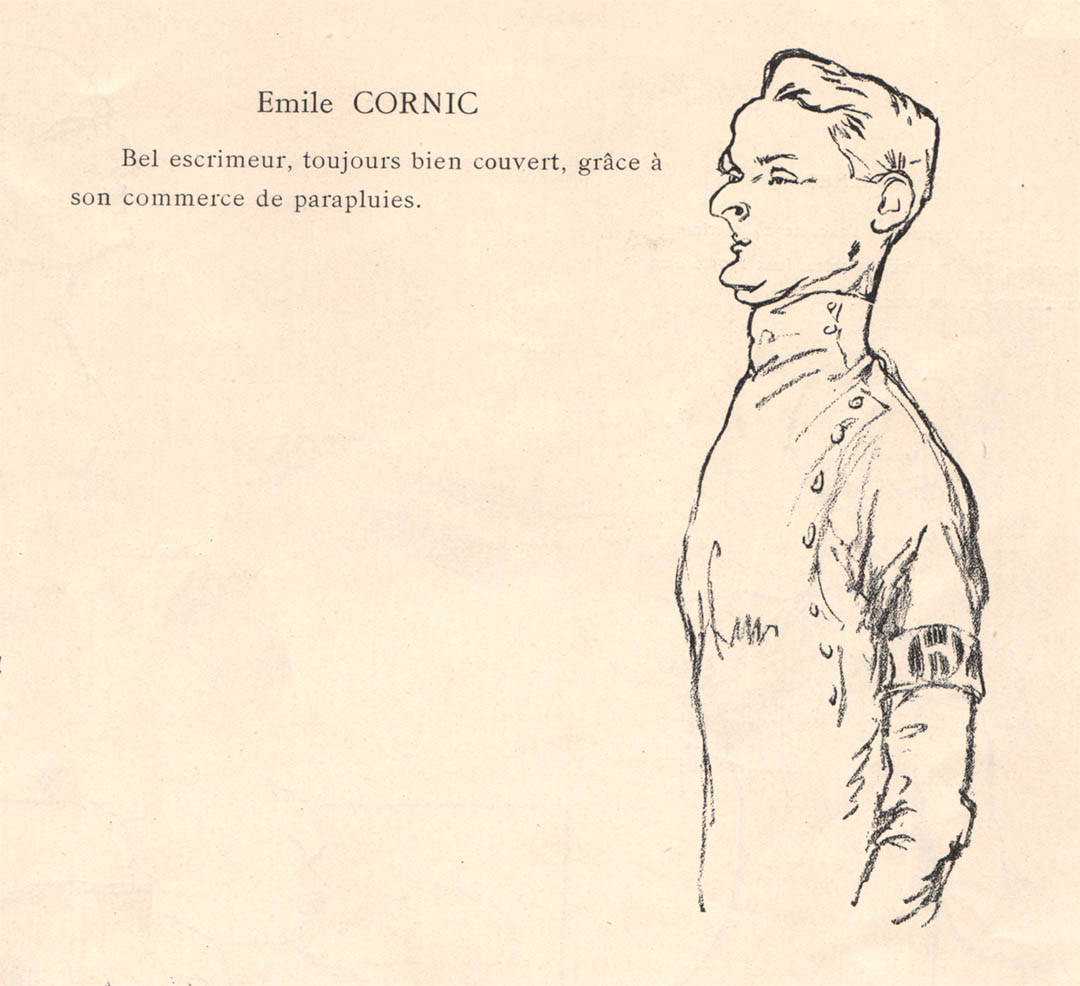

With Google Translate’s assistance, we learn that M. Cornic was a “Beautiful fencer, always well covered, thanks to his trade in umbrellas.” Cornic was on the Silver medal winning 1928 French Olympic epee team and the two met in either ’28 or ’29. Nadi doesn’t recall exactly. Cornic and Nadi fenced at Lucien Gaudin’s home club in Paris, the Automobile Club. Nadi, according to Nadi, crushed Cornic by the score of 30 to 5 or 6 while Gaudin looked on wearing street clothes. Nadi’s take was that Gaudin didn’t want to appear in fencing gear in the same room as Nadi for fear of having to face him. Let’s keep in mind that in 1929 Gaudin would have been 43 and Nadi 30.

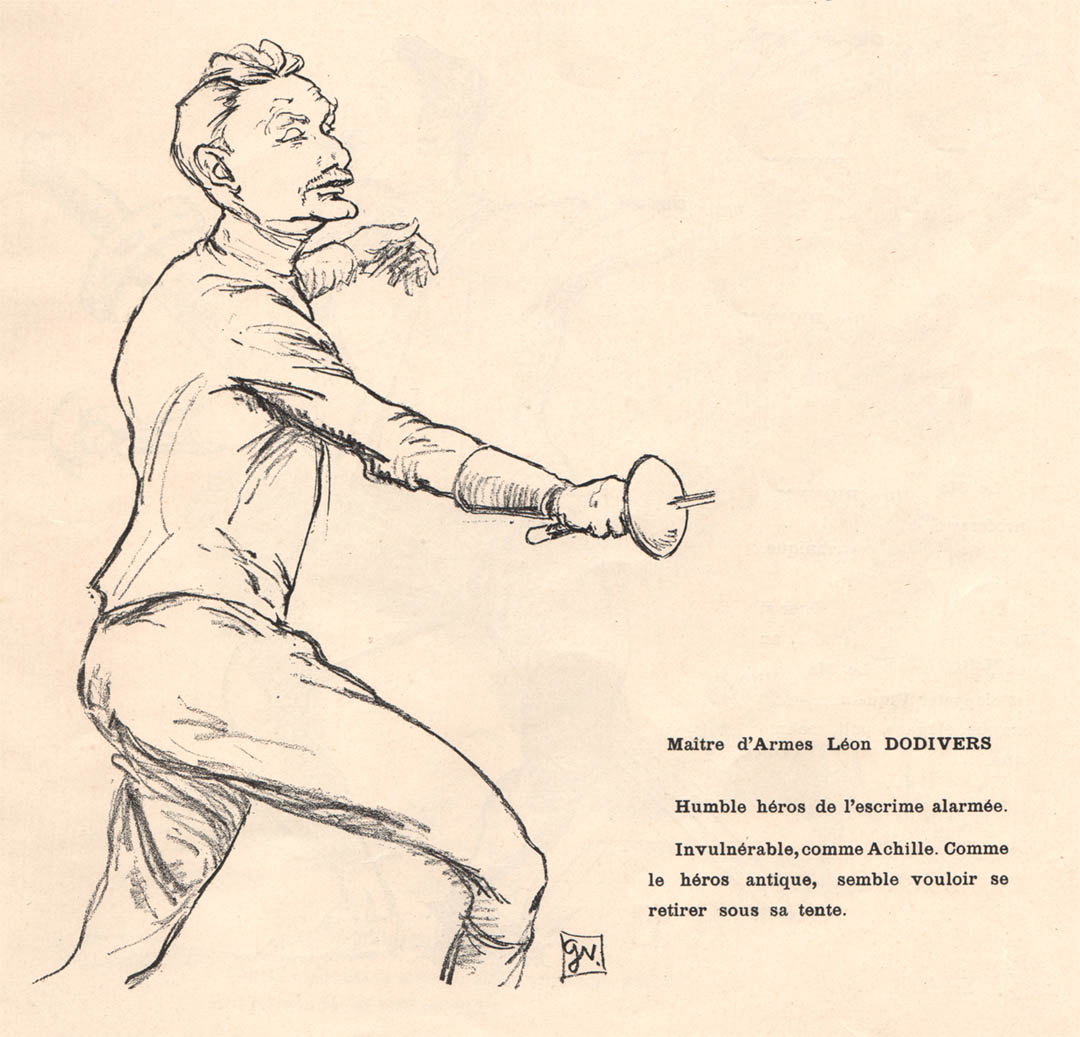

Leon Dodivers was the professional champion of France and Nadi faced him in 1925 at La Baule, a seaside resort in Brittany. Nadi writes that his hand wrap, a commonly used appliance to help keep an Italian foil or epee in your hand, was too tight at the start of the match and his thumb went numb. He kept himself in the match until the break, when he was able to fix his wrap, going on to win the epee match 15-11. Nadi asserts that Gaudin then challenged Dodivers with the intent of beating him by a greater margin than Nadi had, but could only manage a 15-12 victory, Nadi writing further, “…and I can still hear Dodivers from his grave screaming bloody murder that he had been robbed… and indeed he had been, at the opportune moment, by a very able and extremely smart President of the Jury. I was present.”

Ah, Lucien Gaudin. He was among the first to be accorded the title of World Champion (epee, 1921) and he competed at three Olympic Games, 1920-1928, winning 4 Gold and 2 Silver medals. In 1928, he won both the foil and epee Individual Gold. Nadi defeated Gaudin at the 1920 Olympic Games to help Italy to the Team Foil gold. It was unexpected by most, as Nadi was considered a youngster at 21 and Gaudin the old hand. But Nadi faced Gaudin after turning professional in 1922 in Paris and neither forgot nor forgave Gaudin for defeating him in a manner that Nadi objected to most strenuously. And, I may say, not without reason. One of the concessions he made prior to the 1922 match was agreeing that hits made on the upper part of the arm, normally not considered valid target in foil, would be considered as such for this match. That’s pretty much unheard of. The arm was not, is not, part of the valid target for foil. Clearly, Gaudin had a plan. Nadi shouldn’t have agreed, but did. During the match, Gaudin purposely targeted Nadi’s upper arm – something that most foilists would patently ignore, knowing it to be an invalid hit. Several times during the match, Gaudin deliberately targeted the crook of Nadi’s elbow and was awarded a touch. Nadi took revenge in 1924, defeating Gaudin in a rematch, but that was the last time Gaudin would agree to fence him. In the ensuing years, while Nadi was defeating French fencers up and down the country, news writers made a point of wondering why Gaudin didn’t step in to put the Italian in his place. At one point, Nadi was offered 50,000 francs, an unheard of sum, to face Gaudin. Nadi was perfectly willing, but Gaudin would not agree, thus costing Nadi a nice, fat purse. The other reason that Nadi did not have a particular respect for Gaudin was the story he told of Gaudin’s victory in the Individual epee at the 1928 Olympics. According to Nadi, Georges Buchard, who took the Individual Silver in 1928 to Gaudin’s Gold, claimed that Gaudin, having won the Individual foil and frantic to win the epee as well, begged Buchard to give the final match to him, and apparently Buchard agreed. And that’s the story Nadi told of Lucien Gaudin.

Rene Haussy was the last professional champion to defeat Nadi in the early days of Aldo’s reign, Haussy taking him in 1923 by the score of 16-14. Nadi admits that when Gaudin stepped in to officiate the second half of the match he lost his head and deserved to be beaten. Haussy, however, didn’t avoid a rematch and Nadi defeated him two years later in Florence 14-9. Nadi had himself booked the theater for that re-match, billing it the Professional World Championship, as Nadi was then Professional Champion of Italy and Haussy the same for France. Aldo’s older brother Nedo objected to the title for some reason, no doubt feeling that as the older brother and having more Olympic Gold medals, he shouldn’t be eclipsed by his younger sibling’s title, as he was also fencing professionally. Aldo ignored him.

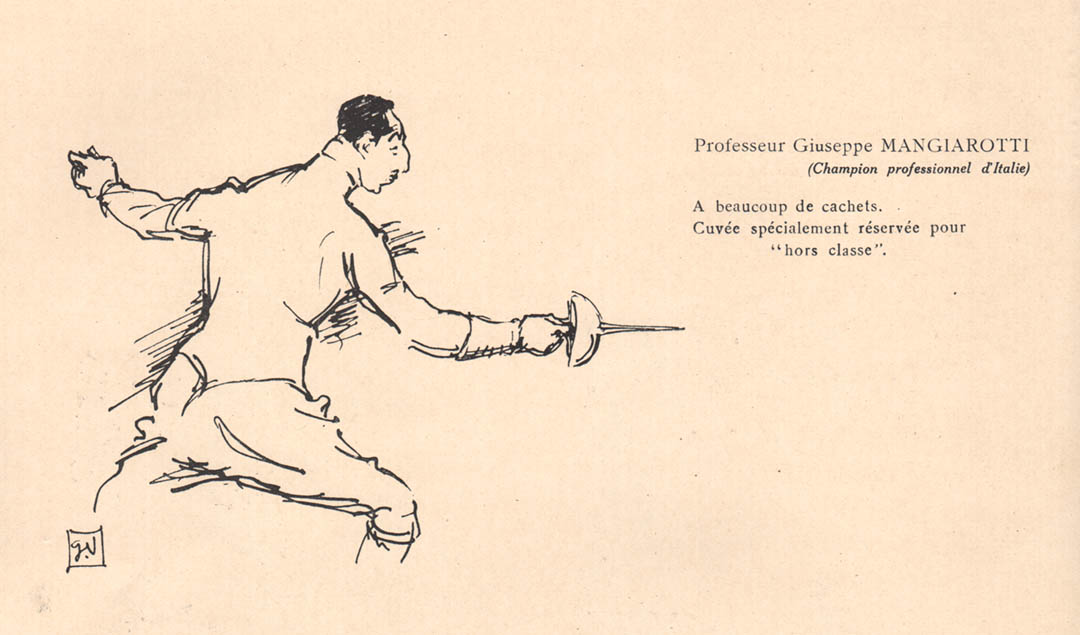

Father of Edoardo, Dario and Mario Mangiarotti, who were great in the following generation, Nadi faced the father, Guiseppe, in 1924 while consolidating his Italian professional championship title in all three weapons. He defeated Mangiarotti in epee 12-8, claiming he could have won without giving up more than 2 or 3 touches, but respected his opponent too much to embarrass him.

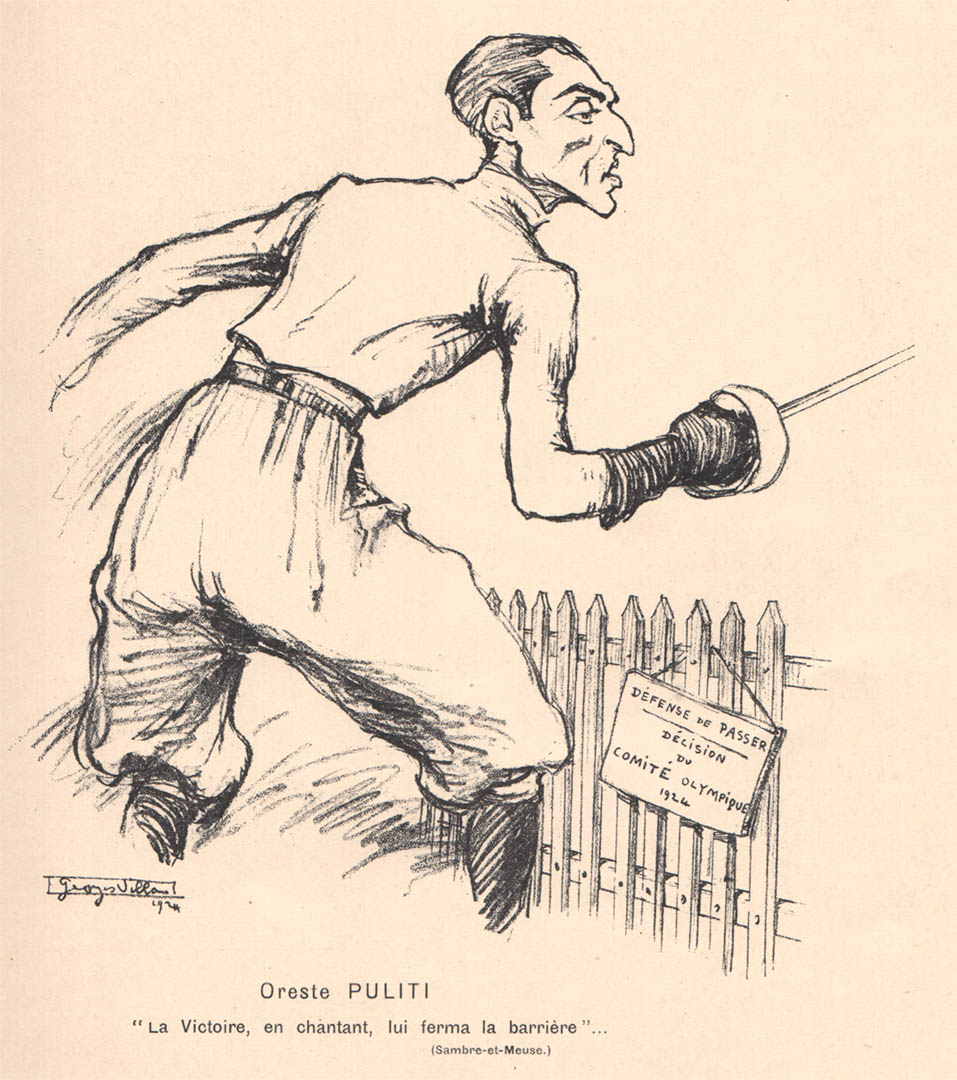

Both famous and infamous, Oreste Puliti was at the center of a controversy that rocked the 1924 Olympics and led to Puliti’s suspension from international competition for 2 years. The central issue was that the Italians were accused in the sabre event with giving touches away to Puliti to give him a better indicator of touches scored vs received as a means to better his chances at taking an individual medal from the dominant Hungarians. Indeed, 1924 was the last time the Italians – or anyone else – defeated the Hungarian sabre team for three decades. But more to the point of his ban, Puliti was incensed when Budapest-based Italian Italo Santelli translated an insult made by Puliti toward an official. The official asked Santelli what had been said and Santelli told him. This led to the Italians protesting, threatening to leave – maybe they did, actually – but also lighting a fuse that eventually led to a duel being fought. The Italian sportsman and news writer Adolfo Contronei wrote unkind words about Italo Santelli and a duel was set. Santelli was keen for the meeting, but his son Giorgio stepped in to fight in his stead. This didn’t make Italo happy, but Giorgio was within his rights according to the dueling code, due to the age of his father. Santelli and Contronei fought and Santelli nearly chopped his head off, wounding him badly with his sabre. Contronei, by the way, is also the man who fought Aldo Nadi in his duel made famous by the written description of it in Nadi’s masterpiece, “On Fencing”. Contronei went on to fight Nedo Nadi after penning yet another unflattering news article regarding the elder of the Nadi boys. Nedo had decided Contronei was a menace to society and needed to be dealt with harshly. He was determined to kill Contronei, but in the moment, struck his opponent’s belt buckle and only wounded him. Contronei, realizing Nadi’s intent, capitulated immediately and never fought another duel.

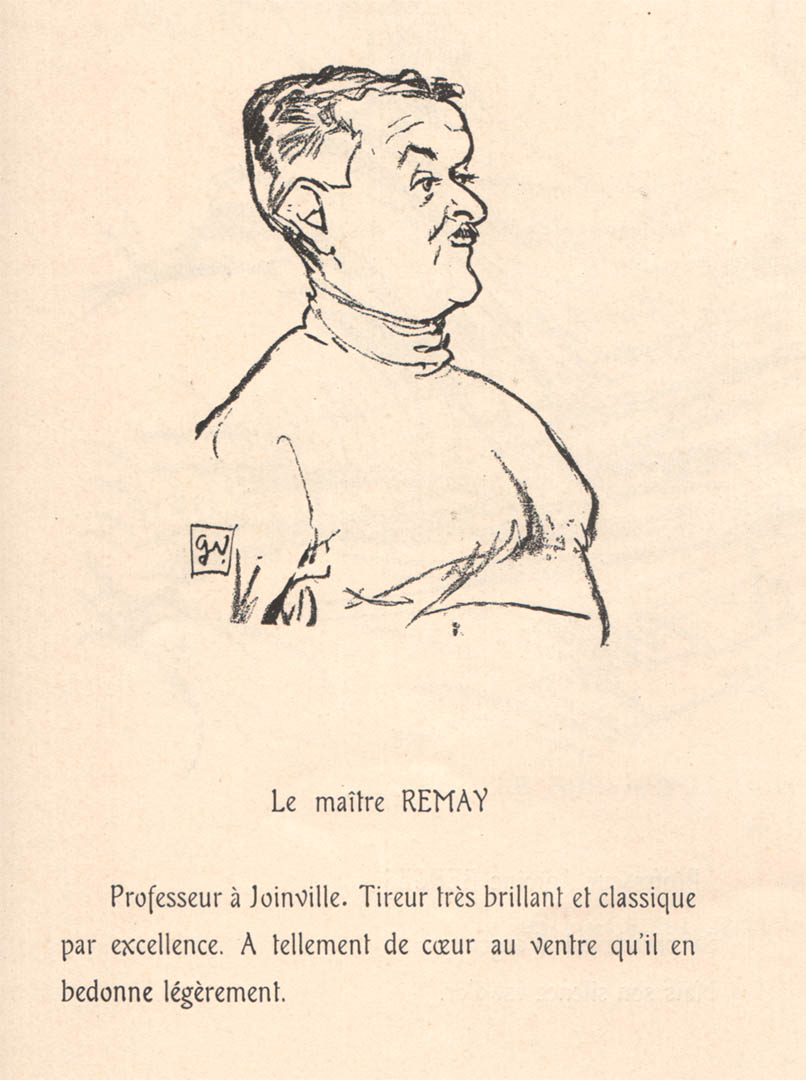

Well, I’m stumped on this one. Le maitre Remay is as good as I can make it. Nadi only mentions that he defeated the head fencing master from the Joinville-le-Pont French Military school in Paris in 1923 by a score of 12-3, but nothing about a first name. He was much more excited in the aftermath of the event, when the great French master Louis Merignac, at 80 years of age, approached Nadi with tears in his eyes and simply shook his hand without saying a word. Nadi clearly couldn’t ask for a greater testament to his performance,

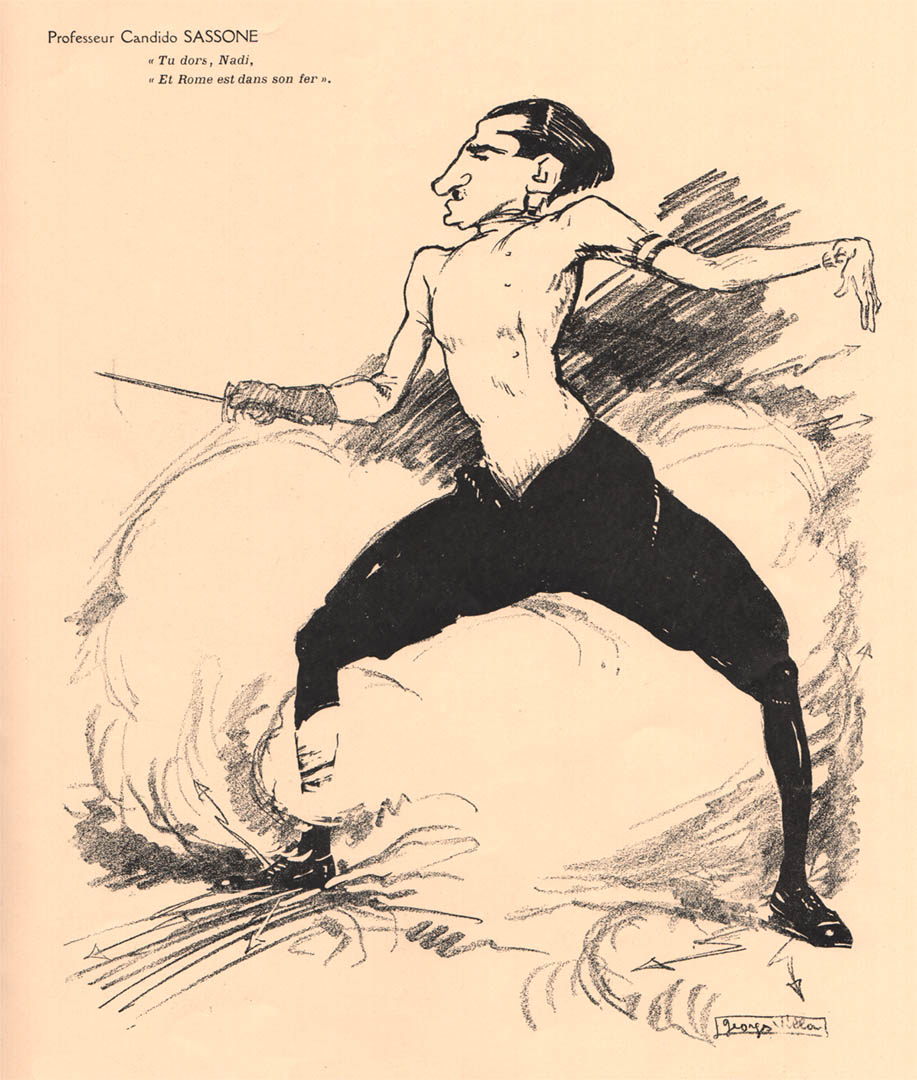

The last of the bunch. A great caricature of Candido Sassone who defeated Nadi soon after Nadi’s defeat by Gaudin. In Nadi’s opinion, due to his anxiety over the defeat by Gaudin, anyone could have beaten him. However, just a few weeks later, Sassone and Nadi fought again, with Nadi slightly ahead at the break and going untouched in the second half of the match. He relates that after the bout, Sassone exclaimed that he couldn’t understand how Nadi could have been so out of sorts as to let himself be defeated in their first encounter. Speaking of encounters, Sassone is probably most famous for his long-running feud and duel with Aurelio Greco that took place in 1922. Apparently they argued – about some topic of fencing history, of all things – and fought a number of encounters to no result until, in the seventh meeting, Sassone took a small wound, ending the affair in Greco’s favor. However, it did not result in a reconciliation. By 1925, Sassone had left Italy for Bueno Aires and spent the rest of his life teaching in Argentina with great success.

Nadi fought many others that are mentioned in his Record, but these are the ones who are also fortunate inclusions in this fantastic book of illustrations by Georges Villa. The book itself came to the Archive thanks to a donation of a large collection of material from John McDougall. After several years and an Excel spreadsheet detailing everything in the entire collection, I continue to find surprises when I go through this gift from John.

Delightful visually and verbally!

But…

I believe there was a period when foil touches on the upper arm were valid. (As they should be — why should I be able to defend myself by allowing my arm to be disabled?

As a unrepentant foilist, I shudder to think of the upper arm as target. But I admit that my knowledge of out-of-date rules is limited. Heck, I’m still getting used to the reversal of the lights. I’m glad you enjoyed the story, Stephen!