My first impression of Peter Schifrin was formed by my reaction to seeing his sculpture work used in a poster for a fencing tournament. It was a photo of his sculpt of his teammates, Vinnie Bradford and Stacey Johnson, and I was fascinated by it. Both were left-handed Texans, Vinnie tall and lithe with dark hair, Stacey a fiery blonde, and both became Olympic fencers. The poster was for the NorCal Fencing Championships and it was in a glass case in the entry way of what was then the main gym at San Jose State University. It was the summer of 1978 and I had arrived for a fencing camp with Michael D’Asaro and Charles Selberg. Peter’s name was under the photo with the caption, “Sculpture by Peter Schifrin”. All I knew about him was that he was the top epee fencer in the San Jose State program under Michael. Seeing the poster, I realized he was also an artist and if the piece in the photo was an indicator of his skills, I was excited to see more.

As it turned out, I got to know Peter well over the next few years. In the fall of 1979, I started at San Jose as a transfer Junior. Peter was red-shirting that year and his loss to the epee team left a hole that Michael decided to fill by trying out his plethora of foilists to see who’d be a candidate to move over to the epee team. I got the nod from Michael after a day where all of us fenced epee while he took note of what was happening. For the following season, with Michael busy with his more experienced fencers, Peter became my epee coach.

Peter strikes a classic pose in a photo taken by my brother, Garrett Nichols, to help Peter create a brochure he used to assist with fundraising for training expenses during his push toward making the 1984 Olympic epee team.

Peter retired from competition after making the ’84 Olympic team, sculpting and teaching fencing in the Bay Area for a few years before returning to school to pursue his MFA, traveling across the country to Boston University. While there, he also put his Prevost D’Armes to use and was instrumental in helping two women foil fencers, MJ O’Neill and Molly Sullivan, make the 1992 Olympic team. Since that time, he has been an instructor of sculpture, teaching at a number of schools, and for the last 15 years or so at the Academy of Art in San Francisco. His work hasn’t entirely left his sport behind.

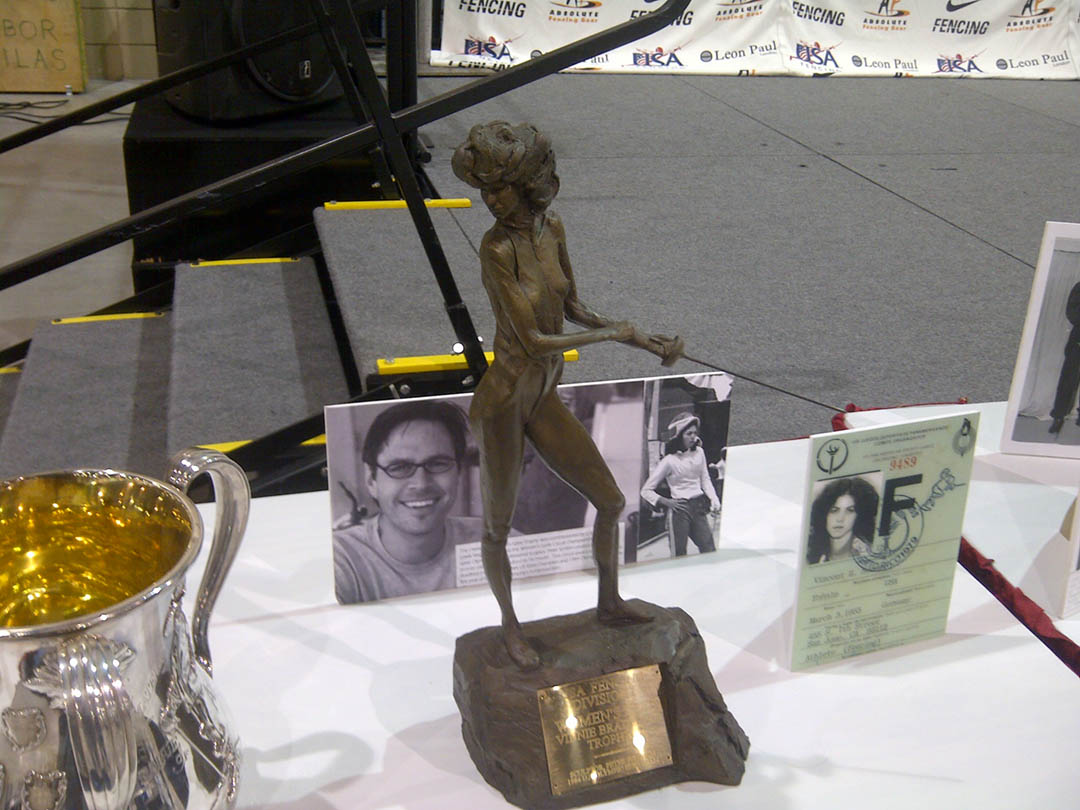

Peter used Vinnie Bradford as a source of inspiration again for this small bronze that is now the perpetual trophy for the US Women’s Epee National Championship. In between championships, this piece now resides with Andy Shaw at his Museum of American Fencing. Back when we had National Championship events, before our coronavirus world, Andy would bring all the perpetual trophies to the competition for presentation to the winners after the dust had settled. Vinnie, a four-time winner of the National epee title, holds the distinction of being the only woman to have won both the epee and foil titles in the same year.

Peter’s work has grown and developed over the years and he has had numerous commissions for large bronze sculptures, both public and private. He has done work that adorn buildings and bridges, and others that dominate landscapes. But whether he works at small scale or large, his work is very personal and shows the artist’s hand in the print of palm and fingers that have pushed the clay into their final form. This Archive, too, is the fortunate recipient of one of Peter’s smaller works, the pre-cast clay sculpt of the bust of Michael D’Asaro, who coached both of us in college, and Peter to his Olympic berth.

The final bronze version that Peter gifted to his coach, Michael D’Asaro.

The clay bust that was molded to create the final bronze now resides in the Archive and it captures Michael in a visceral, magnetic fashion. A man I knew well, in many moods and forms, is encapsulated in this shaped clay. This angle, too, is the one that resonates with me. Michael’s eyes looking this way, his love of life caught like a perfect snapshot. I’ve never seen the final bronze, but this fired clay is a masterful representation of the Michael I knew.

Just a couple of years ago, Peter again turned his hand to sculpt a fencing-themed piece. In this case, two pieces. These were produced at the behest of Connie Yu at The Fencing Center in San Jose where, some 40-ish years ago, Peter was one of the program founders and an early coach. If I remember the story right, Peter was asked to produce a single piece and was working on two different versions to see which one Connie responded to. As it happened, she liked both, so both were cast and are now, in their full bronze glory, on display at the club. Unfortunately, I don’t have photos of the bronze versions (why don’t I have photos of the bronze versions?) but I do have photos of the final versions in clay.

These are around two and a half or three feet tall, and rest on pedestals. Like much of Peter’s figurative work, they speak to form and strength, reaching for, and attaining, goals. In broad strokes, he encapsulates the human form and his figures embody a sense of movement and purposeful direction. It was a thrill to learn that Peter had been chosen to produce a sculpture that would grace the entryway of the soon-to-open US Olympic/Paralympic Museum in Colorado Springs.

Peter’s inspiration for this figure was Al Oerter, the four-time Olympic Gold medalist in discus. The discus was Oerter’s only event, and he gave it his all. Over the course of four Olympic cycles, from 1956 to 1968, he won that singular event, taking the Gold each time. He is the epitome of the athlete who excels under the greatest strain. He only once was favored to win and often wasn’t the top qualifier on the US squad. But when the light of the Olympics would shine upon him, he produced his greatest results. He set multiple world records, won Gold in 1964 with torn rib muscles and a pinched cervical nerve that required him to wear a neck brace while throwing, and in 1980 at age 44, after years of retirement, he finished fourth in the National qualifiers, just missing selection for the Moscow team. Oerter is in a small group of Olympians with a singular achievement. Only five athletes, 4 men and 1 woman, have won Gold in an individual event at four successive Olympic Games. No one has ever done it five times.

This larger-than-life sculpt of Peter’s has just recently been installed in the entry way of the new museum which is waiting for an abatement in the coronavirus to throw its doors wide. Peter’s work will be greeting visitors to this site for years to come, inviting them to embrace the physical accomplishments of the human form through the history of Olympians and Paralympians.

This massive bronze is a great testament to Peter’s understanding of the power within the human body. He expressed this in his own being as an athlete. Tall and strong, Peter had a classic style as a competitive fencer and was unquestionably my personal role model as I attempted to emulate his form, while remaining entirely unable to match his level of results.

Peter influenced me in so many ways. As my fencing coach for a year, he impressed upon me the need for focus and concentration, and the desire to strive for precision in my movement and action. Our coach, Michael D’Asaro, was from the school of thought that the path to victory lay in the perfection of your actions. That first year at San Jose, Peter was the one who ingrained that deep into my psyche. At the same time, he personified to me the mindset of an artist. His approach to viewing the world was through the lens of his art, and it shone through in how he spoke, the questions he asked, the view he took of events. In later years, my career in managing artists for the animation industry was certainly colored by the lessons I, unbeknownst to him, took from Peter, and I can’t say it was an equal exchange. During my time at Pixar, Peter asked if he could bring along two of his sculpture students who were interested in animation to have lunch with me at the studio. While discussing the role that sculptors play in the art process, I mentioned that my own career was achieved almost by happenstance. I said that during college, I was best known for doing two things: fencing, and watching cartoons. Peter almost fell out of his chair laughing. He said, “Oh my god, it’s true! We all wondered what you would do with your life. ‘What will Doug do with himself? All he does is watch cartoons.'” It turned out, watching a lot of cartoons got my foot in the door at a small animation studio. From there, I was able to make my place as an artist manager. Getting to know Peter and learning something of the artist’s mindset was my first lesson in that realm.

Seeing Peter’s accomplishments over the years has been wonderful. His work has range and a rough beauty that I truly admire. Knowing that this new piece is enshrined in a place of honor in the US Olympic/Paralympic Museum is a great motivator for me to make plans to get out to Colorado Springs when the world opens for business again.

Peter Schifrin was an excellent fencing coach and has been an inspiration and mentor for hundreds of artists-in-training during his many years as a teacher. While he may never have pursued his accreditation as a fencing master, he’s more than proven his mastery over clay and bronze. When you next find yourself in Colorado Springs, I hope you’ll have the opportunity to stop in and see this creation by an Olympic fencer, celebrating the Olympic ideal.

The artist and his creation:

I am an inspiring student of ceramics, but I am a steady observer of art all my life. Art in all forms keeps me centered and happy. I was influenced my father a jazz pianist at an early age.

The article was thrilling to read about how diverse one can be from the sport of fencing to molding life-size clay forms to ultimately become notable bronze statues! (inspired by cartoons?)

The Liberation of Art!

Awe inspiring!!!

Thank You!!!!