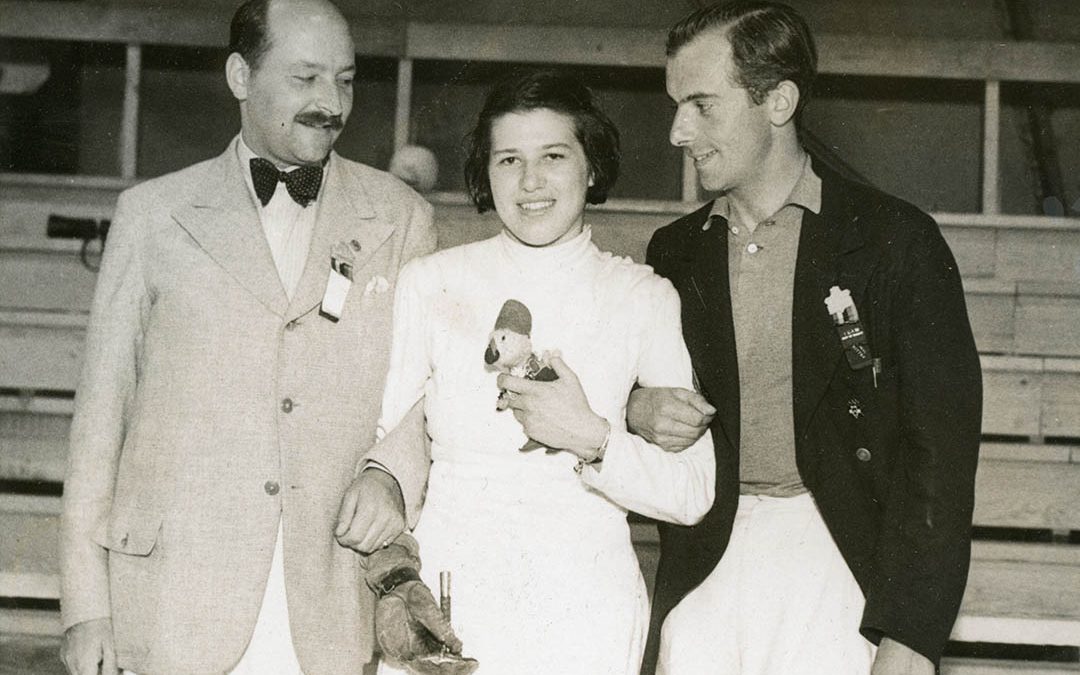

One of my favorite subjects to write about is the famous foilist and Olympic champion, Helene Mayer. There are numerous photographs of her in the Archive collection and since she was based in California for many of her competitive years, her story fits my focus. However, I’ve never looked seriously into the history or background of one of Mayer’s toughest and long-running competitors. When a photo of this woman came up on Ebay, it got me to thinking. The new acquisition is at the top of today’s story, and while we may start with the main subject of that photo, there’s another player involved who piqued my curiosity even more. The woman in the middle up above is the 1932 Los Angeles Olympics Women’s Foil Champion Ellen Preis, later Müller-Preis. Then, just Preis again. I think. She is again in the middle as seen in the photo below:

From a cigarette sports card (think baseball cards, but with smoking), this image depicts the top three women from the finals of the 1936 Olympics, placed according to height. In front, Hungary’s Ilona Elek, who won the Gold Medal. In the middle, Austria’s Ellen Preis, Bronze, and in the back, Germany’s Helene Mayer, Silver.

Preis had, by any measure, a spectacular competitive career that spanned the time from when women competitions at the world level were in their infancy until they stood as firmly established events. At least, in foil. She was a finalist at the 1931 World Championships (3rd place), took the Gold medal at the 1932 Olympics, Bronze in 1936 and won World Championship titles in 1947, 1949 and 1950. She continued to compete at the Olympic level in 1952 (11th) and in 1956 (7th). In Melbourne ’56, she made the final round of eight at the age of 44. She lost 5 of her 7 bouts in that final by one touch. That was also the first Olympic Games with machine-based scoring for foil.

Among the things I won’t write about at length are her Nationalist (read: Nazi) husband Dr. Heinrich Müller, whom she married in 1938 and separated from and maybe divorced near the end of the war (she seems to have kept her married name), and the question as to whether she was or was not Jewish. I’ve read arguments on both sides and have no idea which might be true. Moving on.

Another Ebay treasure I recently purchased. Helene Mayer on the left facing Ellen Preis at the 1931 World Championships in Vienna. (Officially, the European Championships, but the same event that became the Official World Championships in 1937.) Mayer took home her second of three World titles from that event.

It’s been fun running down the long list of accomplishments made by the woman I’d previously thought of mostly as someone who defeated Helene Mayer in Los Angeles in 1932 – even though Mayer finished out of the medals at that tournament. Preis’s career stands on its own, clearly. However, it wasn’t her career that really intrigued me and motivated me to write this story. Rather, it was my surprise and fascination with what I learned about her coach. As far as I know, the coach of Ellen Preis is an Olympic and World first. Ellen Preis was coached throughout her competitive career by her aunt: Elizabeth Wilhelmine “Minna” (Preis) Neralic-Werdnik. Let’s call her Minna. I’ve found only one certain photo of her.

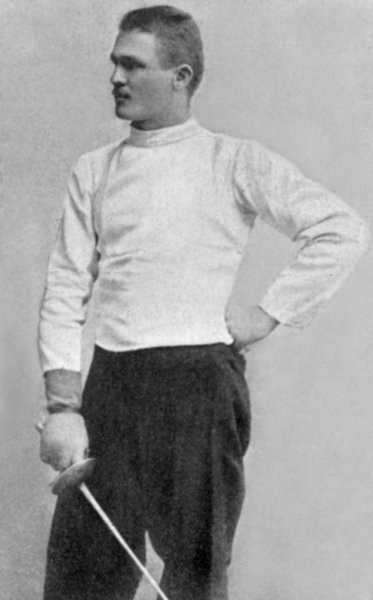

Minna began her fencing career teaching at Universitätsfechtclub in Frankfurt, the city of her birth. Somewhere along the line she met and married Milan (sometimes Michael) Neralic, a fencing master of Croatian decent. He was the first Croatian to win an Olympic medal, taking the Bronze medal in Master’s Sabre in 1900. He earned his fencing masters credential at the famous Austro-Hungarian military school in Weiner-Neustädter under the tutelage of Luigi Barbasetti, who was head of that program from 1894 to 1914. Neralic was a teaching assistant under Barbasetti until 1908 when he moved to Berlin and began teaching at two clubs.

Milan (Mihajlo) Neralic during his time as a foil instructor under Luigi Barbasetti at Weiner-Neustädter. If you’re keeping track of the many mentions of Hungarian fencers and masters on this site, you may be interested to know that Neralic was one of the main teachers of Laszlo Borsodi, the coach of Jekelfalussy (Piller) György (George Piller), who is the subject of my documentary feature, The Last Captain (available here).

The start of WW1 in 1914 saw him move back to Austria and take up a teaching position at the Theresian Military Academy and the Vienna Union Fencing Club. By that time he was married to Minna, how they met, when they married, unknown, and the two were making plans to return to Berlin permanently. However, in 1917 Neralic took ill, was forced to stop teaching, and died in February of 1918. Minna, now a widow, continued to teach women’s classes. From my reading about her history, the consistent reference is that she “focused” on teaching women fencers, but I rather suspect that was a role to which she was subjected rather than chose. At that time, men could teach fencing to both women and men. Women teachers such as Minna likely did not have that same flexibility.

In 1922 (or 1925) Minna re-married. Her second husband was another fencing master, Martin Werdnik. Werdnik had a long and varied career in Vienna and was a founding member of the Vienna Fencing Masters’ Association. He also helped established the forerunner of Austria’s current fencing NGB, the Austrian Fencing Association, originally the Academy of Fencing in Austria. Werdnik volunteered for the army when he was nearly 50 years old and was assigned to teach physical education in Serbia from 1916. In 1917, he was transferred to Italy and received a wound in his right arm. He refused a recommendation for amputation, but never fully regained his previous functionality. After the war he taught exclusively with his left hand. He passed away in 1930, leaving Minna once again widowed. She renamed their club Fencing Hall Werdnik and was the head of that school from then until she retired in 1962.

The instructor that can be vaguely seen in the center back of this photo may be Minna Neralic-Werdnik. Then again, it might be Ellen Preis. This photo is used courtesy of the nice people at the Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, or Austrian National Library. I don’t like using images that aren’t part of my collection without permission, and they couldn’t have been nicer. The young ladies wearing ties in this photo could, maybe should, set a new style for fencers everywhere. Very classy, if you ask me.

There are some widely divergent views on where and when Preis began taking fencing instruction from her aunt Minna. Her Wikipedia entry is very certain that she was Jewish and an Olympic champion after only 2 years’ instruction. With no opinion on the first, I take issue with the second point, as it’s just too unlikely. Preis moved from Berlin, where she was born, to Vienna at some point and it is in Vienna that she would have been trained by her aunt. Another source suggested she began fencing with her aunt over her mother’s objections when she was 13. I’m leaning toward that second idea. I can’t imagine her (or anyone) challenging for the European Championship title in Vienna in 1931 after one year of fencing. I have the strong notion that a year of instruction won’t get you to Carnegie Hall, because it’s just not enough practice, practice, practice.

Preis wrote an autobiography, or at least, her name is on the cover as author, in 1936 documenting her – up to that point – Olympic career. It’s available in English and German, but only the German editions seem to be for sale. I might have to pick one up from a German book dealer, as my discovery of the book has led to the discovery of a photo of Minna that I didn’t know existed until a couple of sentences ago. Readjusting my count of photos of Minna Neralic-Werdnik to two:

Ellen Preis with Aunt Minna taken in 1936 or thereabouts.

The other nickname for Aunt Elizabeth Wilhelmine “Minna” (Preis) Neralic-Werdnik is a rather telling one. She was known professionally as “Ms. Professor Werdnik”, which indicates that, more than just being considered a ‘fencing instructor’, she was considered a full Master. “Professor” was, at that time, a commonly used title synonymous with Master, to the best of my knowledge. (I base that on reading about Generoso Pavese, who was trained at the Scuola Magistrale Militare di Scherma in Rome and went by the title “Professor” in the US.) Several sources simply referred to her as a “Fencing Master”, so I’m sticking with that. It’s my assumption that that title, for women at that time, was a rarity. I’d love to know different.

When she retired in 1962, she had been teaching for 55 years, which means she began teaching around 1907. Fencing Hall Werknik was renamed Fencing Club Werdnik in 1955, with Ellen serving as its president for many years. It finally closed its doors in 1986. Minna passed away in 1980 at the age of 94 and Ellen in 2007 at the age of 95. Long-lived genes in that family.

The one for certain photograph of Minna that I knew about before starting to write this story.

That final photograph was probably taken in the early 1950s, or thereabouts. Ellen is older and Minna (who can just barely be seen) is older still, but I love getting a chance to see even a tiny glimpse of the inside of Fencing Hall Werdnik. And really, by this point in their partnership, I don’t imagine Ellen actually needed to be reminded to keep her back arm up and her back knee bent, but fencing masters will be fencing masters, especially for a press photo opportunity, I think I’m going to hop over to my Advanced Book Exchange tab and see if I can still nab that copy of Ellen’s book. Dust jacket and everything. My German reading comprehension is non-existent, but I’m patient and know where Google Translate lives, so maybe I can glean a little more information about Ms. Professor Werdnik, the first woman to coach an Olympic fencing champion.