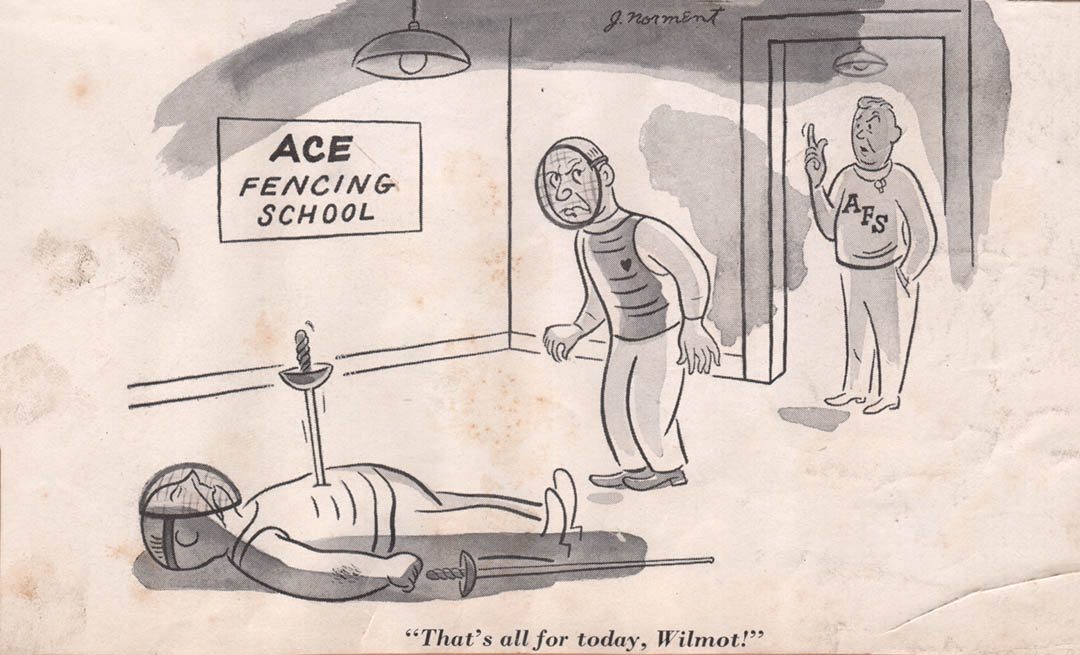

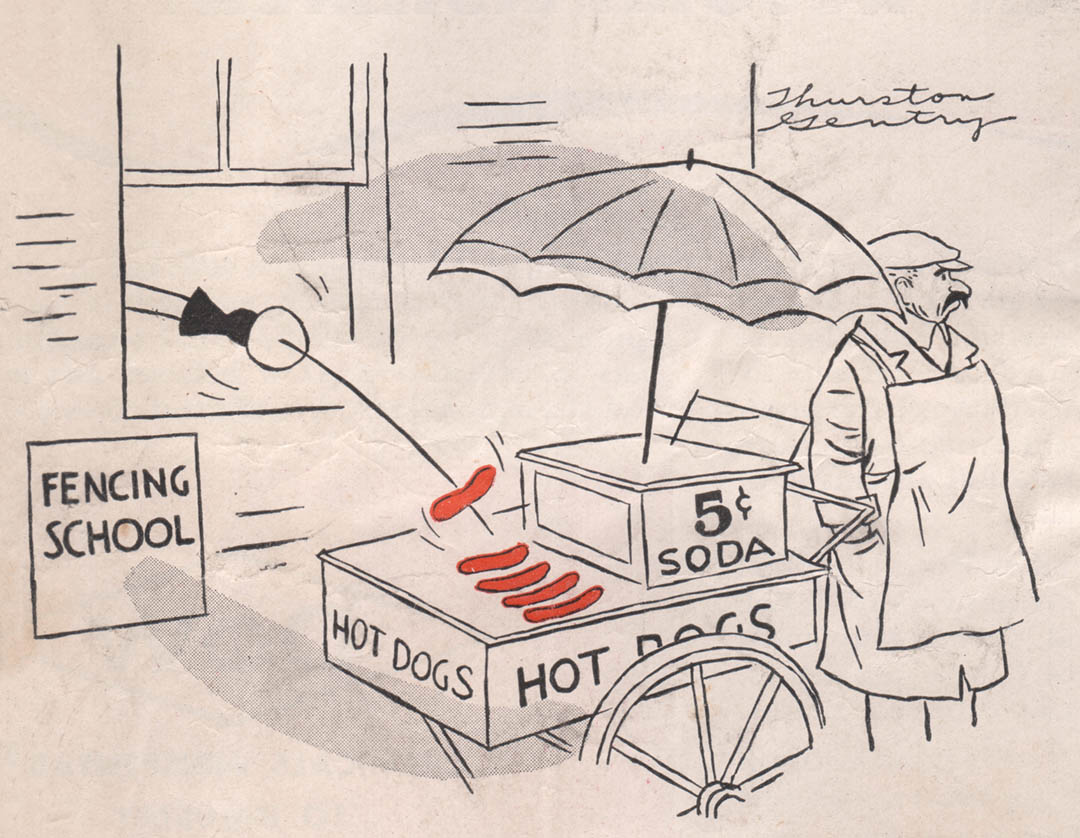

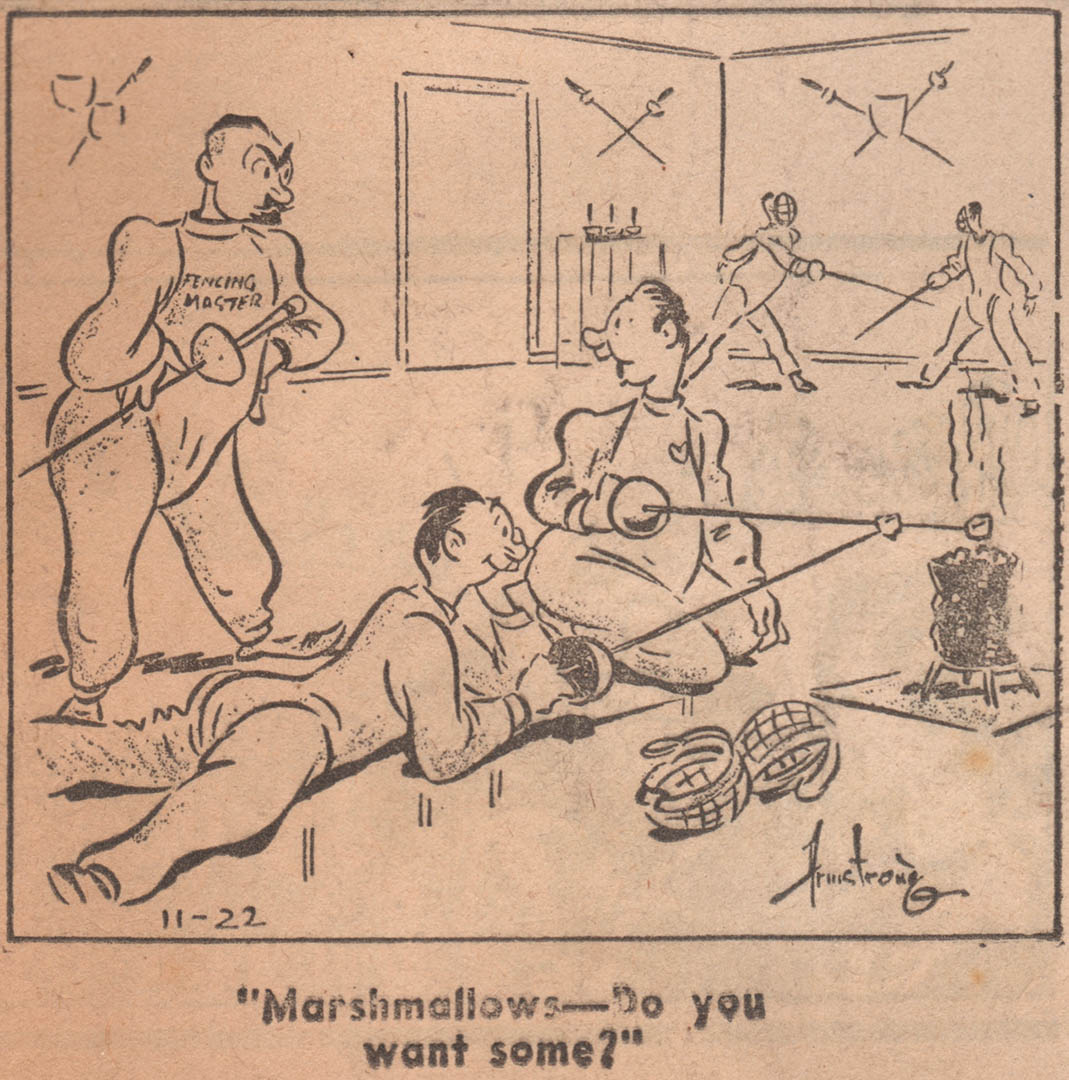

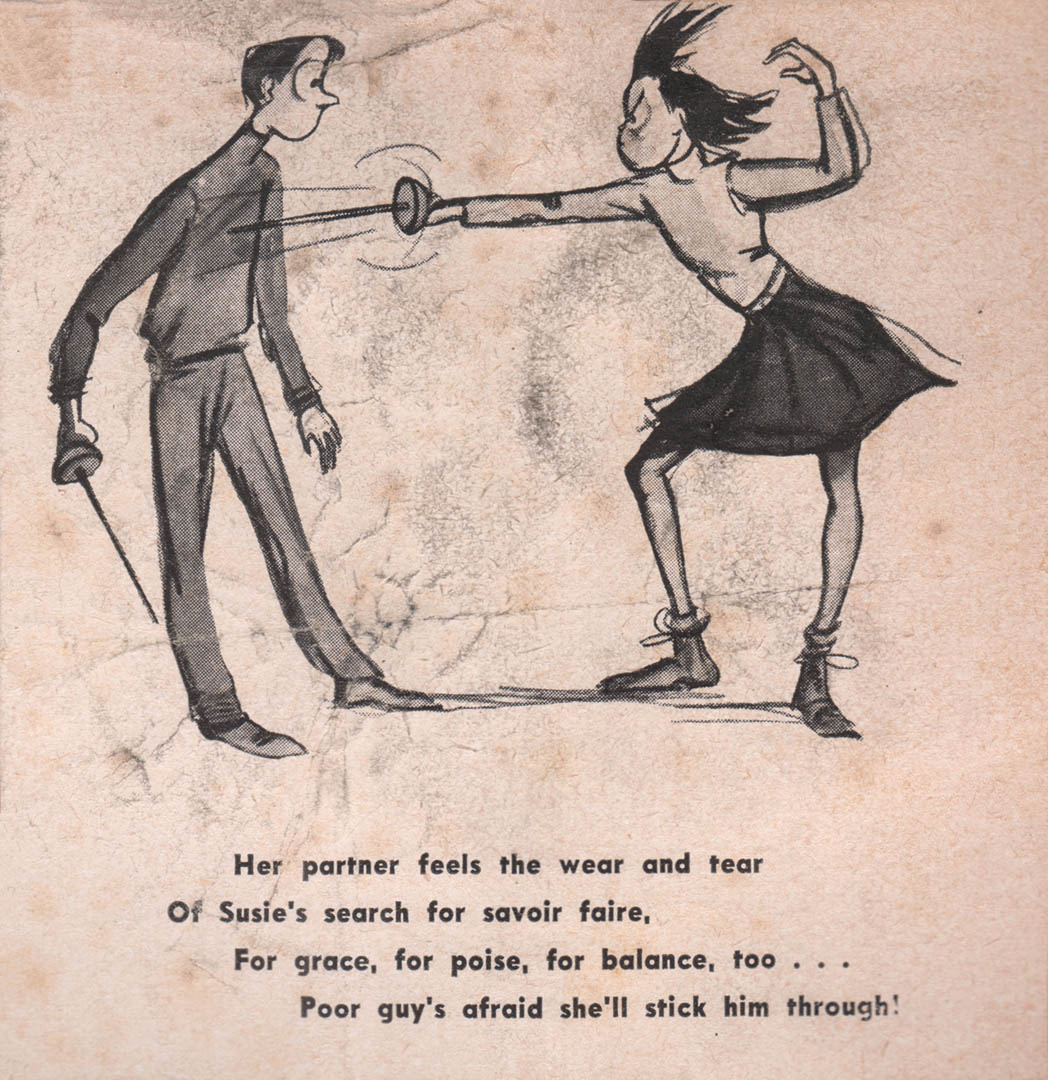

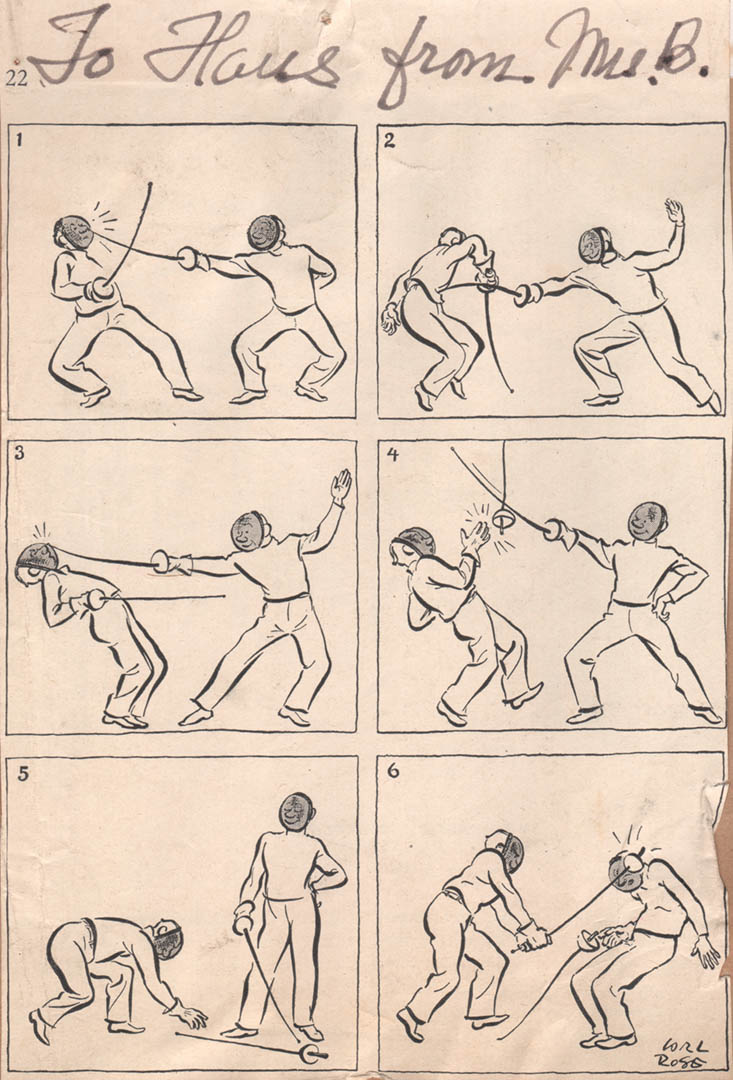

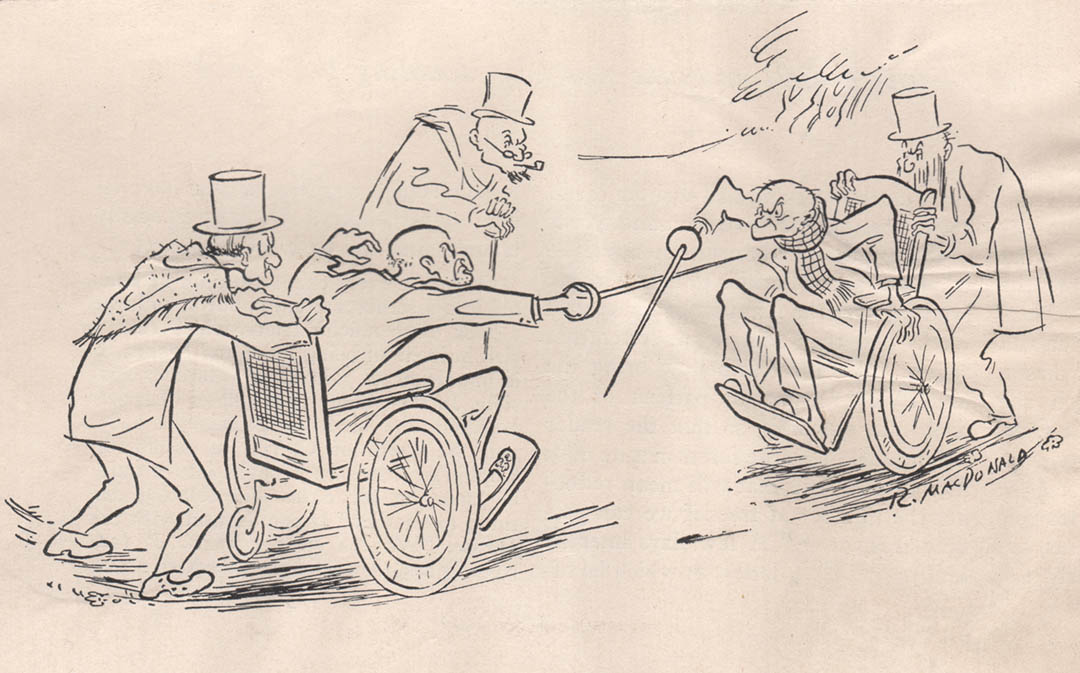

While I continue with my task at hand, scanning the newly donated Hans Halberstadt scrapbooks, I couldn’t help but take a little time to put together a collection of the comics Hans pasted inside the pages of his information-dense collection of ephemera. The scanning is going well and I’ve completed the first scrapbook. There are 110 pages – that’s counting front and back as two pages, since Hans used both sides – adding up to 181 unique scans, mostly 600 dpi/tiff files, which takes up 23.21 gigabytes. There are more scans than pages in the book because some have multiple layers on a page; cards you can open, magazine articles taped on top of one another, etc. There are also some little tiny photo prints that I scanned at higher resolution. Some of these I scanned at 1200 dpi. Some really small ones, contact prints of 35mm negatives cut from a proof sheet (do young people even know what any of that means?) I scanned at 2400 dpi. They came out pretty good, too!

I had to learn some new techniques for this scrapbook. There were some pages that had folded corners or edges, small tears, especially along the bottom edge of the book and some of the multi-layered magazine pages had become wrinkled and folded over like an origami puzzle piece. In looking at my go-to for advice on how to conserve paper ephemera without damaging the original (that would be Google), I found some interesting techniques and a few research papers that dropped knowledge bombs on me. The research papers gave me an idea of what product to buy for pH Neutral mending tissue to repair the small tears. Most of the tears are on newspaper or magazine articles that are already yellowed and faded, so I needed to use something that wouldn’t increase the speed of degradation of the original. Fortunately, my local art supply house had some material that was of reasonable quality. I don’t really have enough need to purchase the high-end bulk material that came on rolls of 2 kilometers or some such ridiculous amount of tape. The other trick was determining how best to deal with small folds. If they can be folded back to their original state – and stay in place long enough for me to scan the page on my flatbed scanner – that’s all I need. Unfortunately, some of the folds didn’t want to cooperate. I could carefully fold them back to its original shape, but they’d been folded so long, they would revert to the new normal as soon as I took my fingers off. Enter, the ordinary household iron! By using unbleached parchment paper, which I stock for all my baking needs, I could safely use the iron (cotton setting) to flatten out the most difficult folds without damaging the paper. It didn’t take much contact, applied right on the folded seam, and the paper would lie flat for at least as long as it took me to move it to the scanner. Some of them reverted to their most comfortable state after, but many remained flattened.

What the future holds for these scrapbooks is mostly a comfy residence inside of an acid-free storage box (they’re here! Yay!) that will reside with other scrapbooks in my Archive storage area. That, at least, assures that they won’t rapidly deteriorate any further than they already have. A future that involved a great deal of handling would not be in their best interest. Interestingly, these books show the kind of wear that could only have come from a great deal of individual perusal. They’ve been looked at a lot. It’s kind of nice knowing that. Whether Hans kept them out and available at the club while he was alive or they got looked at a ton after his passing, I can’t say. A lot of both would be my guess. Like the cartoons on today’s post, there’s something in these books for everyone.

The best thing about these particular books is that it is possible to scan the full pages. The binding on both is loose and tied with rope for the larger and string for the smaller. By making lots of documentary photos, I was able to take apart the first book, scan it, and reassemble it and re-tie the knot as it was. The smaller book, which I’m getting ready to scan, has an even trickier knot, but string is easier to deal with than rope, so I don’t anticipate any issues with getting it back together in its original form. More interesting, the string on both the front and back pass through plastic pegs that originally went through the book to protect the pages from having their punched binder holes from damage against naked string. All four of the plastic pegs are no longer inserted through the binding holes and are just hanging around on the string doing no good to anyone. That’s probably the reason this second book has so many loose pages. The binder holes are torn through due to contact with the string. So, while I can fix that problem and re-insert the pegs, I’m up in the air on repairing the torn holes. Turns out, much to my surprise, that those little reinforcing holes don’t seem to be available in an acid-free version. Clear, yes, but I don’t want to introduce a repair that could lead to further degradation. With all the study I’ve been doing on making certain I’m being a good caretaker of the material in the Archive, I’ve learned that if you can’t be sure you’re not going to introduce a problem for future generations, doing nothing is better.

So I’ll use the best practices I’ve figured out to date, scan everything (file naming convention: HH.Orig.SB2_xxx.description), reassemble this second book basically as-is and gently place it in the acid-free box and leave it alone. That is, by far, the easier solution than what I have to figure out for another, even older, original scrapbook in the Archive collection of scrapbooks. The scrapbook of Erich Funke d’Egnuff began with his move to the Bay Area in 1934 and contains, almost exclusively, news clippings and handbills announcing upcoming events. I’ve done a rough pass of photographing everything in the books, but the binding, as far as I can tell, doesn’t disassemble. Short of cutting every page out of the binding (Blasphemy!!) there isn’t a safe way to put the pages on a flatbed scanner. Some books do ok on my A3 sized scanner (roughly 11×17, the largest reasonably priced oversized flatbed scanner available. Any larger size jumps up your hardware costs into the several thousands of dollars range) without damaging the spine, but the Funke scrapbook is too tightly bound and the taped and glued clippings often go into the curve of the binding. Even if I didn’t care about maintaining the integrity of the spine, which I do, I’d still get a warped scan in the binding area. So that’s out.

One of the early tools I took advantage of for the Archive was a DIY book scanner kit that was gifted to me. It was from an online file and made with a laser cutter at a Maker Space my wife was a member of when we lived in the East Bay. We were there one evening and the only other guy in the place overheard us talking while I tested out the book scanner that was assembled and available. Turns out, the guy working there that evening was the same one who’d put together the book scanner I was trying out and he’d cut out two sets of parts. He didn’t need the second one and said I could have it. I had to cobble together a few other necessary parts after reading the assembly directions, things like nuts & bolts, bungee cords and skateboard bearings (I bought Reds). Fortunately, putting it together was pretty easy and by getting two small cameras, I was able to “scan” small to medium sized books and folios. The device uses a lever that draws the open book up into two glass plates that flatten the pages. While holding the lever, you click one camera shutter, switch hands, then the other shutter. The cameras I bought won’t shoot any format except .jpegs, and you have to assemble the pages one at a time from two sets of files – one left-hand pages, the other right-hand pages, but it’s a reasonably easy way to scan a book.

The reason for all that backstory is that I can’t use the book scanner for the Funke scrapbook. It’s too large to fit in the cradle. I’ve been imagining creating a rig that would achieve the same result as the book scanner using an old wooden picture frame to hold the glass and creating a surrounding box of as-yet-unknown design to hold the camera. You’d brace the book open (carefully), shoot one page, then turn the rig around and shoot the facing page. Issue #1: how much pressure can you apply to flatten the page without straining the glass? Issue #2: the glass can’t be too thick. Issue #3: the glass edge that presses into the seam of the binding needs to be super smooth so as not to cut the book. Blah, blah, blah. I could keep going. That’s why I haven’t built it yet. I’ll figure it out at some point.

Back to the task at hand, I’ll start scanning Scrapbook #2 this week. It’s disassembled and ready to go and I don’t want to leave it like that too long. Not that it will be disturbed where it is, but I just don’t like projects this sensitive to linger undone. It has fewer pages than the first book, but may take just as long or longer to scan. Each page seems to have some issue with tears or folds. Or both. Now that I’ve got the page flattening technique down, I’ll likely be spending quite a bit of time prepping each page prior to scanning. The pages of the news clippings and such are still reasonably pliable. They go back into shape without much stress. The pages of the scrapbook itself are a little more brittle and I have to be careful not to cause any chipping. So far, so good.

I think that’s all the news for the week. Not entirely sure why I decided to ramble about process while showing comics. Hopefully no one is feeling too victimized and that the comics make up for the interstitials commentary. Truthfully, I can’t say I’ll never do it again. I’m having too much fun with all of this not to share what’s going on as I face new problems that need solutions, or just attention. I guess this all points out why I’d be such a lousy super-villain. On my VillainYelp page, it would probably read something like, “Defeatability rating: Easy. Strong tendency to monologue. Mention scanning formats or favorite archival material websites, then look for an opening.”